No Books, No Credit: Japanese Supreme Court on Denying Input Tax Credit for Failure to Present Records

Date of Judgment: December 16, 2004

Case Name: Claim for Revocation of Tax Disposition (平成13年(行ヒ)第116号)

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

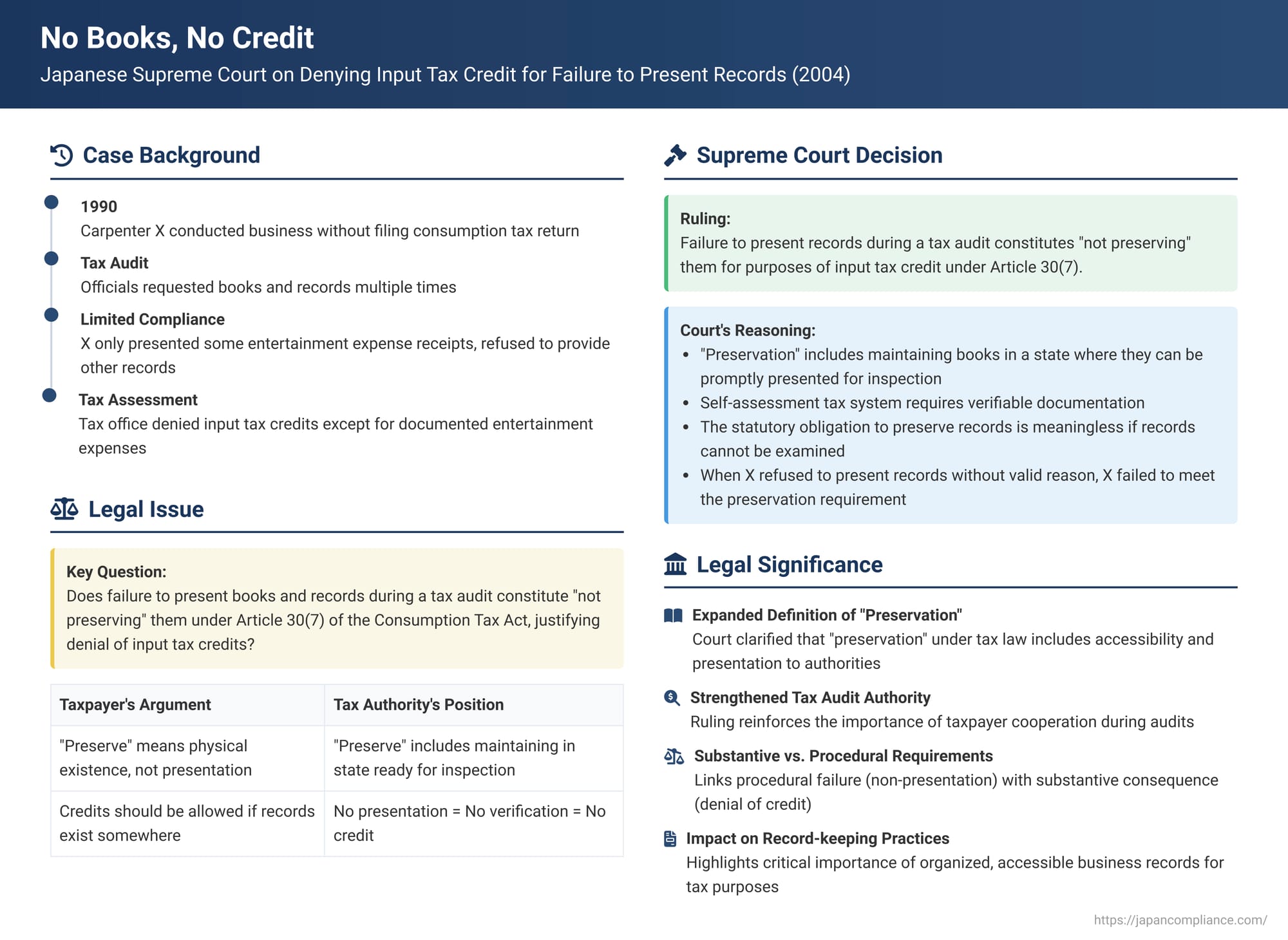

In a significant ruling on December 16, 2004, the Supreme Court of Japan addressed the consequences for a taxpayer who fails to present their books and records during a tax audit for consumption tax purposes. The Court affirmed that such non-presentation can lead to the denial of input tax credits, effectively interpreting the statutory requirement to "preserve" records as meaning to preserve them in a manner that allows for timely inspection by tax authorities.

The Carpenter's Case: Unfiled Returns and Unseen Records

The appellant, X, was an individual proprietor operating a carpentry business. For the taxable period in question (calendar year 1990, referred to as "the subject taxable period"), X did not file a consumption tax return. Furthermore, while X had filed income tax returns for 1990 and other relevant years, these returns were incomplete; they did not specify the gross revenue or necessary expenses related to his business income, nor did they include any attached supporting documentation detailing these figures.

The head of the competent tax office, Y, initiated a tax audit of X to determine the correct amount of consumption tax payable for the subject taxable period and to verify the accuracy of X's income tax declarations. Tax officials made multiple visits to X's residence, requesting him to present all relevant books and documents and to cooperate fully with the investigation. Despite these repeated requests, X's compliance was minimal. He only presented some receipts related to entertainment expenses incurred in 1990 and failed to provide any other books, ledgers, or invoices related to his business activities. The tax officials noted that there was nothing unlawful about their requests and that X provided no particular reason for his inability to comply.

Faced with this lack of cooperation and documentation, Y proceeded to make a tax determination for X's consumption tax liability for the subject taxable period. Y calculated X's output tax based on the gross revenue from X's carpentry business that the officials were able to ascertain through their investigation. However, for the input tax credit—a crucial mechanism in the consumption tax system that allows businesses to deduct the tax paid on their purchases from the tax collected on their sales—Y adopted a strict stance. Input tax credit was allowed only for the consumption tax related to the entertainment expenses that could be verified from the receipts X had actually presented. For all other taxable purchases X might have made, Y disallowed the input tax credit. This disallowance was based on the tax office's interpretation of Article 30, paragraph 7 of the Consumption Tax Act (CTA) (the version before the 1994 amendment was applicable to this case). This provision essentially states that input tax credit is not applicable if "the enterprise does not preserve books or invoices, etc., related to the input tax credit for taxable purchases, etc., for the said taxable period." Y also issued a non-filing penalty.

X challenged these dispositions through administrative appeals. The National Tax Tribunal partially cancelled the initial dispositions, but the core issue concerning the denial of the input tax credit due to non-presentation of records remained. X then filed a lawsuit seeking the cancellation of the (revised) dispositions. Both the Maebashi District Court and the Tokyo High Court ruled against X, upholding the tax office's denial of the bulk of the input tax credits. X subsequently appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Core: Input Tax Credit and the "Preservation" Requirement

Japan's consumption tax is a multi-stage tax levied on the supply of goods and services. A key feature designed to prevent tax cascading (tax on tax) and ensure that the burden ultimately falls on final consumption is the "input tax credit" (仕入税額控除 - shiire zeigaku kōjo), as provided in Article 30, paragraph 1 of the CTA. This allows businesses to deduct the consumption tax they paid on their business-related purchases (taxable inputs) from the consumption tax they collected on their sales.

However, this right to an input tax credit is not unconditional. Article 30, paragraph 7 of the CTA (old version) stipulated: "The provision of paragraph 1 [granting input tax credit] shall not apply to the amount of tax on taxable purchases, etc., related to such taxable purchases or taxable freight for which the enterprise does not preserve books or invoices, etc., pertaining to the deduction for taxes on taxable purchases, etc., for the said taxable period..." (Later amendments changed "books OR invoices" to "books AND invoices," but this change was not central to the Supreme Court's reasoning on the meaning of "preserve" in this case).

The crucial legal question was: Does a taxpayer's failure to present these essential documents to tax auditors during a legitimate tax investigation equate to a situation where the taxpayer "does not preserve" them, as contemplated by Article 30, paragraph 7, thereby justifying the denial of the input tax credit?

The Supreme Court's Ruling: Failure to Present for Inspection Equals "Not Preserving"

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal concerning the main tax dispositions, thereby upholding the denial of the input tax credit. The Court's decision provided an important interpretation of the "preservation" requirement under Article 30, paragraph 7.

The Court's reasoning can be summarized as follows:

- Importance of Verification in a Self-Assessment System: Japan's consumption tax system, like many of its national taxes, operates primarily on a self-assessment basis. This means taxpayers are responsible for correctly calculating and declaring their tax liability (CTA Article 45, paragraph 1; General Act of National Taxes Article 16, paragraph 1, item 1). For such a system to function effectively and maintain fairness, it is essential that taxpayer declarations are made accurately based on factual transactions, and that tax authorities have the ability to verify these declarations when necessary.

- Taxpayer's Obligation to Maintain Inspectable Records: To facilitate this verification, the CTA imposes obligations on enterprises. Article 58 requires businesses to keep books, record relevant details of their transactions (including taxable purchases), and preserve these books. Article 62 grants tax officials the authority to inspect these books and records to investigate the accuracy of tax declarations. Furthermore, Article 68, item 1 (now Article 127 of the General Act of National Taxes) prescribes penalties for those who refuse, obstruct, or evade such inspections by tax officials. These provisions are designed to enable tax authorities to properly make corrective assessments if declarations are found to be incorrect.

- Purpose and Scope of Article 30, paragraph 7: The Court reasoned that Article 30, paragraph 7—which disallows input tax credit if relevant books or invoices are not preserved—presupposes, much like the general bookkeeping obligation in Article 58, that these documents related to input tax credit will be available and subject to inspection by tax officials. The Court stated that the application of the input tax credit under Article 30, paragraph 1 is contingent upon tax officials being able to investigate and confirm the facts of taxable purchases by inspecting either the books (which must contain the specific details prescribed in Article 30, paragraph 8, item 1) or the invoices and other documents (which must contain the details prescribed in Article 30, paragraph 9, item 1) that the enterprise is required to preserve.

- The Rationale for Denying Credit for Non-Preservation: The Court acknowledged that the consequence of an enterprise not preserving such books or invoices is the denial of the input tax credit under Article 30, paragraph 1. This significant disadvantage was intentionally stipulated, the Court opined, because ensuring adequate tax revenue under a multi-stage consumption tax system—which aims to tax asset transfers broadly and thinly at each stage of the economic chain—deems the preservation of reliable evidentiary documents like books and invoices to be indispensable.

- Defining "Does Not Preserve" in the Context of Audits: Crucially, the Supreme Court interpreted the phrase "does not preserve books or invoices, etc." in Article 30, paragraph 7. It held that if an enterprise has failed to organize the required books or invoices as stipulated by Article 50, paragraph 1 of the Consumption Tax Act Enforcement Order (which mandates organizing these documents and keeping them at the place of tax payment or the relevant business office for a period of seven years) AND has not maintained them in a state where they can be presented promptly to tax officials for inspection during a tax audit conducted under Article 62 of the CTA, then this situation falls within the meaning of "where the enterprise does not preserve books or invoices, etc." as per Article 30, paragraph 7.

- Application to X's Conduct: In X's case, he was repeatedly requested by tax officials to present his books and records. The Court noted that there was nothing unlawful or improper about these requests, and X had provided no particular valid reason for his refusal to comply fully. By only presenting receipts for some entertainment expenses and withholding all other relevant business records, X failed to demonstrate that he had preserved his books and records in a state that allowed for their prompt presentation for inspection by the tax officials. Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that X's situation squarely fell under the "does not preserve" condition in Article 30, paragraph 7. Consequently, the tax office's decision to deny the input tax credit (except for the portion related to the entertainment expenses for which receipts were actually presented) was lawful. (The exception for disaster or other unavoidable circumstances preventing preservation, as provided in the proviso to Article 30(7), was not applicable here).

Analysis and Broader Implications

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision has several important implications for taxpayers and tax administration in Japan:

- Equating Non-Presentation with "Non-Preservation" for Input Tax Credit: The ruling effectively establishes that an unjustified failure or refusal by a taxpayer to present required books and records during a legitimate tax audit can be treated as a failure to "preserve" those documents for the specific purpose of claiming input tax credits under Article 30, paragraph 7 of the CTA. "Preservation," in this context, means more than just physically keeping the documents somewhere; it implies maintaining them in an organized and accessible manner, ready for inspection when lawfully requested.

- Strengthening Tax Audit Authority and Compliance: The decision strongly reinforces the authority of tax officials to conduct effective audits and underscores the critical importance of taxpayer cooperation in providing necessary documentation. It signals that taxpayers cannot simply refuse to present records and then later attempt to claim benefits based on information they withheld during the audit process (at least not without facing the consequences of Article 30(7)).

- Different Legal Perspectives on "Preservation" vs. "Presentation": Legal commentary has explored various viewpoints on this issue. Some argue for a stricter, more literal interpretation of "preserve," suggesting that if a taxpayer can later prove in court that the documents did, in fact, exist and were preserved (even if not shown during the audit), the input tax credit should be allowed (a view expressed in a dissenting opinion by Justice Takii in a related Supreme Court case decided shortly after this one, on December 20, 2004). Others might argue that an unjustified refusal to present documents during an audit is conclusive evidence of non-compliance. The Supreme Court, in this case, adopted an intermediate but firm position: "preservation" includes the practical aspect of being able to present the documents for timely inspection.

- Substantive Requirement vs. Procedural Obstruction: Commentators have noted a conceptual distinction: Article 30, paragraph 7 outlines a substantive requirement (preservation of records) for entitlement to the input tax credit, whereas a failure to present documents during an audit can also be seen as a procedural obstruction of the investigation. The Supreme Court's ruling effectively links these two aspects, making the procedural failure to present (without good cause) indicative of a substantive failure to "preserve" in the manner required by law for claiming the credit.

- Considering Legislative Intent: The Supreme Court's interpretation appears to take into account the broader legislative intent behind the input tax credit system and its reliance on verifiable documentation. Ensuring the integrity of the multi-stage consumption tax, which depends on accurate tracking of tax paid at each step, necessitates robust record-keeping and verification.

This Supreme Court decision was subsequently followed in other related Supreme Court cases, including one from March 10, 2005 (Minshu Vol. 59, No. 2, p. 379), which concerned the revocation of a Blue Tax Return (青色申告 - aoiro shinkoku) approval and similarly emphasized that books and records must be maintained in a state ready for inspection by tax officials.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2004 judgment in this case sends a clear message to taxpayers in Japan regarding their obligations for consumption tax compliance. It establishes that the entitlement to input tax credits is intrinsically linked to the proper preservation and timely presentation of supporting books and records during tax audits. "Preserving" records, in the context of Article 30, paragraph 7 of the Consumption Tax Act, means more than just not destroying them; it encompasses keeping them organized, accessible, and readily available for prompt inspection by tax officials when lawfully requested. A failure to meet this standard, particularly through unjustified non-presentation during an audit, can result in the denial of valuable input tax credits, significantly impacting a taxpayer's final consumption tax liability. This ruling underscores the critical importance of meticulous record-keeping and full cooperation with tax authorities.