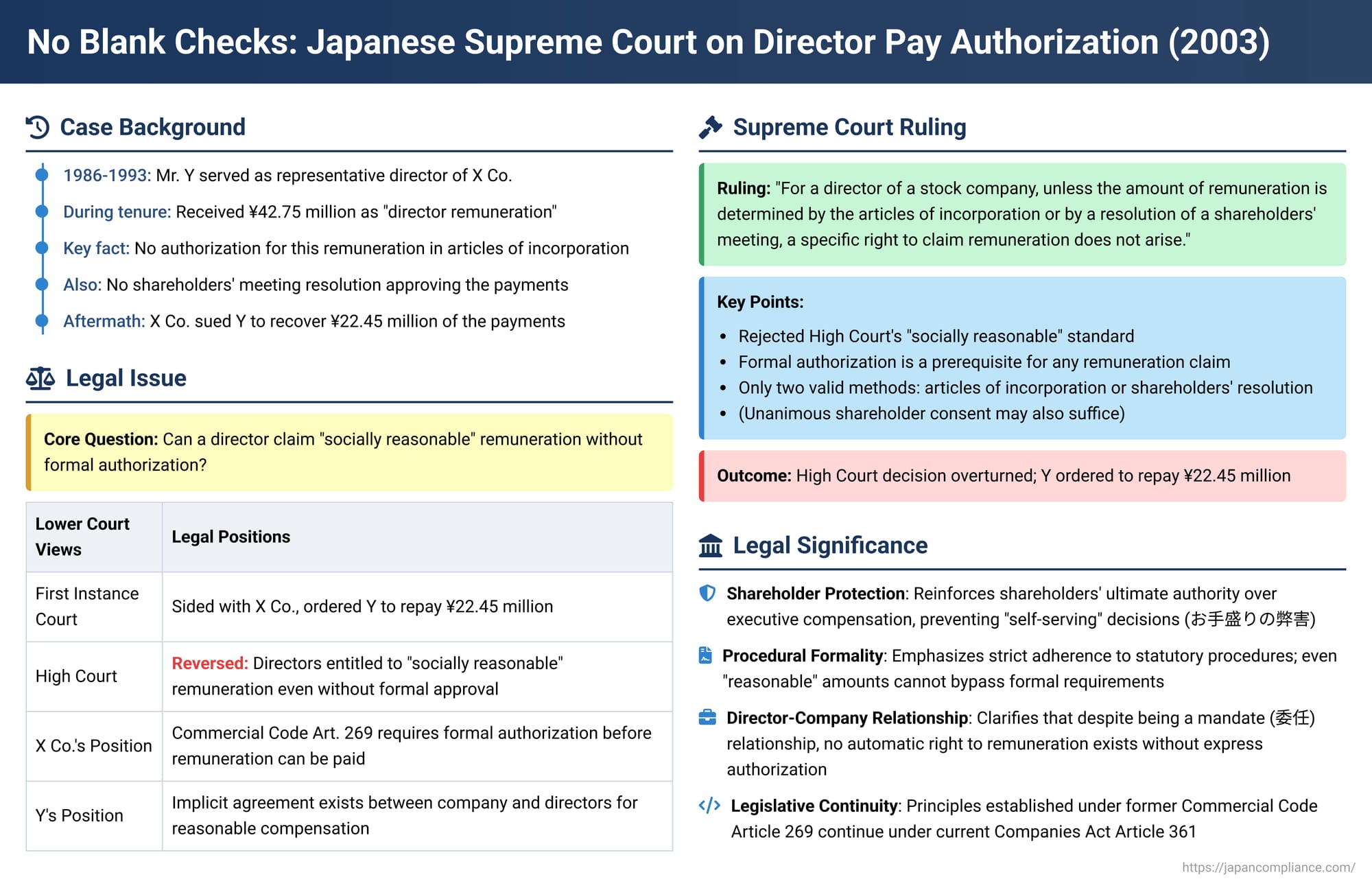

No Blank Checks: Japanese Supreme Court on Director Pay Authorization

Date of Judgment: February 21, 2003

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

Determining the remuneration of company directors is a critical aspect of corporate governance. It directly impacts company expenses and involves individuals who are in positions of power and trust. A key question arises: can directors decide their own pay, or take what they believe to be a "reasonable" amount, without specific, formal approval? Or does Japanese corporate law impose stricter controls?

The Supreme Court of Japan addressed this fundamental issue in its decision on February 21, 2003, emphasizing that a director's right to claim remuneration is not automatic but hinges on explicit authorization through prescribed corporate procedures.

The Legal Framework: Preventing Self-Dealing in Director Remuneration

The cornerstone of Japanese law regarding director remuneration is designed to ensure transparency and shareholder control, primarily to prevent self-dealing. At the time of this case, Article 269 of the Commercial Code (the principles of which are carried into the current Companies Act, Article 361, Paragraph 1) stipulated that matters concerning directors' remuneration—if not provided for in the company's articles of incorporation—must be determined by a resolution of the shareholders' meeting.

The legislative intent behind this rule is clear:

- To prevent directors or the board of directors from engaging in "otemori no heigai" (お手盛りの弊害) – a Japanese term referring to the abuse of making self-serving decisions, particularly regarding their own compensation.

- To entrust the ultimate decision-making authority over director pay to the autonomous judgment of the shareholders, who are the company's owners.

The Case of X Co. and Director Y

The case involved X Co. (formerly Tomaruya Housing K.K.) and its former representative director, Y (Mr. Kido Hideo).

- Mr. Y served as the representative director of X Co. from March 1986 to June 1993. During this period, he received payments totaling 42.75 million yen, which were characterized as director's remuneration.

- Crucially, there was no provision in X Co.'s articles of incorporation that fixed the amount of director remuneration. Furthermore, no resolution had ever been passed at a shareholders' meeting to approve these payments, nor was there evidence of unanimous consent from all shareholders that could have substituted for such a resolution.

- X Co. subsequently filed a lawsuit against Y to recover these payments. The company argued that because the remuneration was paid without the necessary authorization required by Commercial Code Article 269, the payments were unlawful, and Y was liable to repay the amount as damages to the company (under then Commercial Code Article 266, Paragraph 1, Item (v), relating to director liability).

The Lower Courts' Conflicting Views

The case saw differing approaches in the lower courts:

- The First Instance Court: Partially sided with X Co., ordering Y to repay 22.45 million yen of the received remuneration, plus interest.

- The High Court's "Socially Reasonable" Standard: On appeal, the High Court took a different view. It opined that there is generally an implicit agreement (a tacit understanding) between a company and its directors that the directors will be remunerated for their services. Building on this, the High Court reasoned that if no specific shareholder resolution exists setting the remuneration amount, a director should still be entitled to claim a "socially reasonable amount" of compensation from the company. The High Court found that the amount Y had received was not, in fact, more than what could be considered socially reasonable. Therefore, it concluded that the payments did not violate Commercial Code Article 269 and were lawful, reversing the first instance court's order for repayment and dismissing X Co.'s claim for the 22.45 million yen.

X Co. then appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (February 21, 2003)

The Supreme Court, in a unanimous judgment, decisively overturned the High Court's reasoning and reasserted the primacy of formal authorization for director remuneration.

Rejection of the "Socially Reasonable" Standard Without Prior Authorization

The Supreme Court squarely rejected the High Court's approach of allowing "socially reasonable" remuneration in the absence of prior formal authorization. It held that the perceived reasonableness of the amount paid is irrelevant if the foundational legal requirements for authorizing that payment have not been met.

No Specific Right to Remuneration Without Formal Authorization

The Court laid down a clear and unequivocal rule: "For a director of a stock company, unless the amount of remuneration is determined by the articles of incorporation or by a resolution of a shareholders' meeting, a specific right to claim remuneration does not arise, and the director cannot claim remuneration from the company." This means that without one of these forms of authorization, a director simply has no concrete legal entitlement to be paid by the company.

Reinforcement of Shareholder Control and Prevention of Self-Dealing

This interpretation strongly reinforces the legislative purpose of Commercial Code Article 269 (and its successor in the Companies Act). By mandating that remuneration amounts be fixed either in the articles of incorporation (which shareholders approve) or by a direct resolution of the shareholders' meeting, the law places the ultimate control over director compensation firmly in the hands of the company's owners. This structure is designed to prevent directors from unilaterally setting their own pay or using their board positions to approve excessive compensation for themselves without shareholder scrutiny.

Unanimous Shareholder Consent as a Potential Alternative

While the judgment primarily focuses on the two statutory methods of authorization (articles or shareholder resolution), both the judgment text and the accompanying PDF commentary indicate that unanimous consent of all shareholders to the remuneration could also serve as valid authorization. This is particularly relevant for closely held companies where obtaining unanimous consent might be more feasible than a formal meeting and can be seen as functionally equivalent to a shareholder resolution for this purpose.

Outcome of the Appeal

Based on its reasoning, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of the law. Since Y had received remuneration without it being authorized by X Co.'s articles of incorporation, a shareholders' meeting resolution, or the unanimous consent of all shareholders, Y had no legal right to claim that remuneration. The Supreme Court therefore quashed the part of the High Court's judgment that had dismissed X Co.'s claim for the 22.45 million yen. This effectively reinstated the first instance court's decision ordering Y to repay that specific amount to X Co.

Nature of the Director's Contract (Mandate)

The relationship between a company and its director is legally characterized as a mandate (inin) under the Japanese Civil Code (a principle also reflected in Article 330 of the Companies Act). Under the Civil Code (Article 648, Paragraph 1), a mandate is, in principle, gratuitous (unpaid) unless there is a special agreement to the contrary.

Historically, Japanese legal theory and practice often presumed that an implicit agreement for remuneration existed in director appointment contracts, given the nature of the duties. The Supreme Court's 2003 decision does not necessarily negate the idea that there might be an underlying agreement or expectation of remuneration. However, it crucially clarifies that such an underlying agreement, even if presumed, does not by itself create a specifically enforceable claim for a particular amount of remuneration. The statutory requirements of authorization through the articles of incorporation or a shareholders' meeting resolution act as a precondition for the director's right to claim a specific sum to crystallize and become legally enforceable against the company.

Implications for Corporate Governance

This Supreme Court decision has several important implications for corporate governance in Japan:

- Strict Adherence to Formalities: It underscores the absolute necessity for companies to strictly follow the prescribed legal procedures for determining and authorizing director remuneration. Informal arrangements or assumptions of "reasonableness" are insufficient.

- Protection for Companies and Shareholders: The ruling safeguards company assets from unauthorized payments to directors and reinforces the fundamental right of shareholders to oversee and approve director compensation, a key aspect of holding management accountable.

- Clarity for Directors: It provides unambiguous guidance to directors: they cannot assume a right to remuneration, even if they believe their contributions warrant it or the amount seems "fair," unless that remuneration has been properly authorized according to company law.

Conclusion

The 2003 Supreme Court decision stands as a definitive statement on the prerequisites for director remuneration in Japanese companies. It affirms that a director's concrete and legally claimable right to remuneration arises only when the amount has been duly authorized either by the company's articles of incorporation or by a resolution of its shareholders' meeting (with the implicit understanding that unanimous shareholder consent can also suffice).

This ruling firmly prioritizes shareholder control and the robust prevention of director self-dealing over subjective assessments of "reasonableness" when the essential step of formal authorization is absent. It serves as a vital reminder of the importance of procedural correctness and shareholder oversight in the critical area of executive compensation.