No Backtracking in Court: Japan's Supreme Court on Amendments During Trademark Refusal Lawsuits (eAccess Case)

Judgment Date: July 14, 2005

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 16 (Gyo-Hi) No. 4 (Action for Rescission of a Trial Decision)

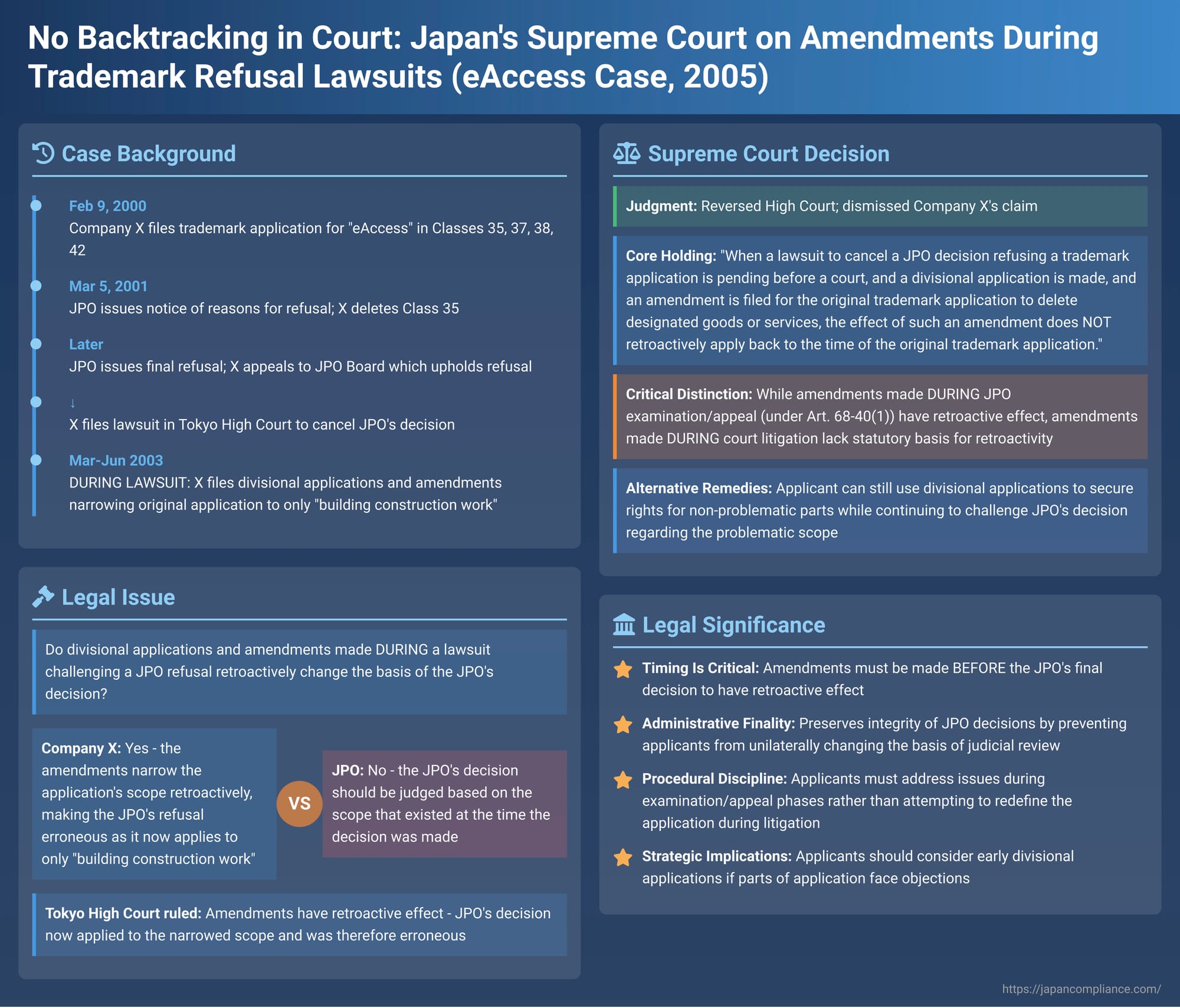

The "eAccess case," decided by the Japanese Supreme Court in 2005, provides a critical clarification on the procedural intricacies of trademark applications, specifically addressing the effect of amendments made to an application after the Japan Patent Office (JPO) has issued a final refusal decision and while a lawsuit to cancel that decision is pending before the courts. The central issue was whether narrowing the scope of designated services through a divisional application during such a lawsuit could retroactively alter the basis of the JPO's original refusal, thereby rendering the JPO's decision flawed. The Supreme Court's negative answer to this question has significant implications for trademark prosecution and litigation strategy in Japan.

The eAccess Application Journey: From Broad Application to Focused Litigation

The case began when Company X (the appellee before the Supreme Court) filed a trademark application on February 9, 2000, for the mark "eAccess" (the "Original Application"). The application initially designated a broad range of services across four classes under the then-effective Trademark Order:

- Class 35 (referred to as Service Group A)

- Class 37 (Service Group B)

- Class 38 (Service Group C)

- Class 42 (Service Group D)

On March 5, 2001, the JPO issued a notice of reasons for refusal. In response, Company X filed an amendment deleting Service Group A from the designated services. Despite this amendment, the JPO issued a final decision of refusal (拒絶査定 - kyozetsu satei) for the remaining services.

Company X appealed this examiner's refusal to the JPO's appeal board. The appeal board, in a trial decision (審決 - shinketsu) (the "JPO Refusal Decision"), upheld the examiner's refusal. The board found that the "eAccess" trademark was similar to a prior registered trademark owned by another party, and that the designated services in the "eAccess" application were identical or similar to those covered by the cited prior mark. This constituted a ground for refusal under Article 4, Paragraph 1, Item 11 of the Trademark Law.

Dissatisfied with the JPO Appeal Board's Refusal Decision, Company X filed a lawsuit with the Tokyo High Court seeking its cancellation (rescission). This is where the procedural complexity deepened. While this lawsuit was pending before the High Court, Company X undertook two strategic divisional applications (分割出願 - bunkatsu shutsugan) pursuant to Article 10, Paragraph 1 of the Trademark Law:

- In the first divisional application (March 11, 2003), Company X carved out all services in Service Group D from the Original Application.

- In the second divisional application (June 2, 2003), Company X carved out all services in Service Group C and the majority of services in Service Group B, leaving only "building construction work" (建築一式工事 - kenchiku isshiki kōji) from Service Group B in the Original Application.

Concurrently with these divisional applications, Company X submitted procedural amendments (手続補正書 - tetsuzuki hoseisho) to the JPO for the Original Application, formally reflecting the reduction of its designated services to solely "building construction work."

In the ongoing High Court lawsuit, Company X then argued that these post-JPO-decision divisional applications and the resultant amendments had fundamentally changed the scope of the Original Application. Since the services that had formed the basis for the JPO's refusal (due to conflict with the prior mark) were now removed from the Original Application, Company X contended that the JPO Refusal Decision itself was based on an erroneous (outdated) understanding of the designated services. Therefore, the JPO's similarity assessment was flawed, and its decision should be cancelled.

The Tokyo High Court's View: Divisional Applications Retroactively Change the Game

The Tokyo High Court accepted Company X's argument and ruled in its favor, ordering the cancellation of the JPO Refusal Decision. The High Court's reasoning was:

- When a valid divisional application is filed, the designated goods or services of the original application are automatically and inherently divided between the original application and the new divisional application(s). The removal of services from the original application (those now forming the divisional application) is an intrinsic effect of the divisional application itself and does not require a separate procedural act to be effective.

- This reduction in the scope of designated services in the original application means that the subject matter of the lawsuit challenging the JPO's Refusal Decision is also automatically narrowed to the remaining services. The court should then adjudicate the lawfulness of the JPO's decision concerning these remaining services, although the temporal point of reference for the JPO's decision itself remains the time it was made.

- In the eAccess case, following the two divisional applications, the only service remaining in the Original Application was "building construction work." The High Court found that this specific service was not identical or similar to the services covered by the prior registered trademark cited by the JPO in its refusal. Therefore, the JPO Refusal Decision, when assessed against this now-narrowed scope, was, in outcome, erroneous. The High Court concluded that the portion of the JPO's decision effectively pertaining to "building construction work" should be cancelled as unlawful, and the remainder of the JPO's decision had lost its practical effect due to the services being moved to the divisional applications.

The JPO Director General appealed this Tokyo High Court decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Amendments During Litigation Don't Rewrite History

The Supreme Court overturned the Tokyo High Court's judgment and dismissed Company X's original claim to cancel the JPO Refusal Decision. The Supreme Court's core holding was:

"When a lawsuit to cancel a JPO decision refusing a trademark application is pending before a court, and a divisional application is made, and an amendment is filed for the original trademark application to delete designated goods or services, the effect of such an amendment does not retroactively apply back to the time of the original trademark application."

Therefore, the JPO's Refusal Decision – which was correctly based on the broader scope of designated services as they existed at the time the JPO made its decision – does not become erroneous in outcome simply because the applicant later narrowed that scope during litigation. The Supreme Court found that the High Court's contrary interpretation was a clear error of law that affected the judgment.

The Supreme Court's Reasoning and Elaboration

The Supreme Court's decision hinged on a careful interpretation of the provisions governing divisional applications and amendments in the Trademark Law.

- Divisional Applications and Amendments: Two Contexts

- While an Application is Pending at the JPO:

- Trademark Law Article 10, Paragraph 1 allows an applicant to divide an application designating two or more goods or services into one or more new applications. This can be done while the application is pending in examination, appeal, or retrial at the JPO, or even when a lawsuit to cancel a JPO refusal decision is pending in court. The crucial benefit, under Article 10, Paragraph 2, is that such new divisional applications are deemed to have been filed at the time of the original application.

- If a divisional application is made while the case is still at the JPO, Article 68-40, Paragraph 1 of the Trademark Law allows the applicant to amend the original application (e.g., to delete the goods/services that have been moved to the divisional application). Such amendments made under Article 68-40(1) are generally understood to have retroactive effect back to the original filing date of the application. This means both the newly created divisional application and the amended original application (with its reduced scope) are treated as separate applications, both benefiting from the original filing date, and both proceed through examination or appeal accordingly. The applicant enjoys considerable flexibility in how they apportion goods/services between the original and divisional applications during this JPO-pendency phase.

- The PDF commentary notes that this broad ability to divide and amend with retroactive effect while an application is at the JPO is a feature of Japanese trademark law that is more flexible than corresponding provisions in Japanese patent law, and is partly explained as aligning with requirements of the Trademark Law Treaty (TLT Article 7).

- Divisional Applications and Amendments During a Lawsuit to Cancel a JPO Refusal Decision:

- This was the scenario in the eAccess case. While Article 10(1) permits the filing of divisional applications even when a lawsuit challenging a JPO refusal is pending, Article 68-40(1)—the provision that grants retroactive effect to amendments—explicitly limits its applicability to situations where the application is pending before the JPO (i.e., in examination, opposition review, appeal, or retrial). It does not extend to the period when a lawsuit is pending in court.

- The Trademark Law Implementing Regulations (at the time, Article 22, Paragraph 4; now Article 22, Paragraph 2) do require that when a divisional application is filed (whether the case is at the JPO or in court), an amendment to the schedule of goods/services in the original application must be filed simultaneously. This is for procedural neatness to reflect the division.

- The Core Legal Question: The Supreme Court had to decide if an amendment made pursuant to these Implementing Regulations during a lawsuit should be given the same retroactive effect as an amendment made under Article 68-40(1) while the application is pending at the JPO. The High Court had effectively said yes, arguing that the retroactive nature of the divisional application itself (under Art. 10(2)) inherently implied a retroactive change to the original application's scope.

- While an Application is Pending at the JPO:

- The Supreme Court's Stance on Retroactivity During Litigation:

- The Supreme Court firmly rejected the High Court's view. It reasoned that an amendment made to the original application during a pending lawsuit, even if filed simultaneously with a divisional application as required by the Implementing Regulations, is not an amendment under Article 68-40, Paragraph 1. Therefore, there is no statutory basis in Article 68-40(1) for such an amendment to have retroactive effect.

- The Court found no other provision in the Trademark Law that would grant retroactive effect to amendments made at this stage.

- To allow retroactive effect to amendments made during a lawsuit would, in the Supreme Court's view, contravene the legislative intent of Article 68-40, Paragraph 1, which deliberately restricts the timing of such retroactive amendments to periods when the application is still within the JPO's jurisdiction. The Court referenced its own 1984 decision (Showa 56 (Gyo-Tsu) No. 99, decided October 23, 1984), which held that a partial abandonment of designated goods made after a JPO refusal decision and during a subsequent lawsuit does not have retroactive effect to the application date.

- Protection of Applicant's Interests: The Supreme Court also addressed the concern that denying retroactive effect might unduly harm applicants. It pointed out that an applicant whose application is refused due to issues with only some of their designated goods/services is not left without a remedy.

- They can utilize Article 10, Paragraph 1 to file divisional applications for the non-problematic goods or services. These divisional applications will benefit from the original filing date (under Article 10(2)) and can proceed to examination and potential registration if they independently meet all requirements.

- The original application, now effectively narrowed by the non-retroactive amendment (which serves to define what remains for the lawsuit), would still be subject to the JPO's Refusal Decision concerning those remaining (and presumably problematic) goods/services. The applicant can continue their lawsuit to argue that the JPO's decision was incorrect for those specific remaining items based on the circumstances as they existed when the JPO made its decision.

- Thus, the Court concluded, denying retroactive effect to the amendment of the original application during litigation does not prejudice the applicant's ability to secure rights for the unobjectionable parts of their original application, nor does it conflict with the purpose of Article 10 regarding divisional applications.

Legal Rationale and Broader Principles

The Supreme Court's decision in the eAccess case aligns with a broader principle concerning the finality and integrity of administrative decisions.

- Finality of Administrative Decisions: Once the JPO, as the competent administrative authority, has issued a final decision (like a refusal decision in an appeal trial), that decision is based on the facts and scope of the application as it stood at that time. To allow a private party (the applicant) to unilaterally and retroactively alter the very subject matter of that administrative decision through actions taken during subsequent judicial review would undermine the stability and predictability of the administrative process, unless there's a specific legal provision that explicitly permits such retroactive alteration by the applicant at that stage.

- Comparison with Patent Law: The PDF commentary notes that while the patent system in Japan has a mechanism like a "correction trial" (訂正審判 - teisei shinpan) which can, through a separate administrative procedure, retroactively alter the scope of a granted patent, the type of unilateral amendment attempted by Company X during litigation does not have an equivalent with retroactive effect in trademark law for changing the basis of a past JPO refusal.

- Correcting Overly Applicant-Friendly Interpretations: The commentary also suggests that the eAccess decision, similar to the 1984 Supreme Court ruling on post-refusal partial abandonment, can be seen as a move by the Supreme Court to correct a perceived tendency in some earlier trademark law interpretations to be excessively accommodating to applicants, potentially allowing them to revise the terms of engagement even after a formal administrative decision had been rendered. This ruling brings a stricter procedural discipline.

Practical Implications for Applicants and Litigants

The eAccess case has clear practical implications:

- Strategic Timing of Amendments: If an applicant anticipates that certain designated goods or services in their application might face objections, and they wish to narrow the application to avoid refusal for the entire application, it is crucial to make such amendments (e.g., deletions) before a final JPO refusal decision (either by the examiner or the appeal board) is issued, if they want those amendments to be considered retroactively as defining the scope of the application for that decision.

- Effective Use of Divisional Applications Post-Refusal: If a JPO refusal decision has already been issued covering multiple goods/services, and the applicant believes the refusal is only justified for some of them:

- They can file divisional applications for the goods/services they believe are registrable. These divisional applications will retain the original filing date and will be examined (or re-examined) on their own merits.

- For the original application (which will now, after the non-retroactive amendment, formally list only the disputed goods/services), the lawsuit challenging the JPO's Refusal Decision will proceed. The court will assess the correctness of the JPO's decision based on that narrowed (but originally refused) scope, as it stood when the JPO made its decision. The subsequent narrowing via divisional application does not change the historical basis of the JPO's decision being reviewed.

- Understanding the Scope of Judicial Review: The case clarifies that judicial review of a JPO refusal decision is a review of the correctness of that specific administrative decision at the time it was made, based on the application as it then existed. It is not a de novo re-examination where the applicant can freely redefine the application's scope during the litigation itself and expect that redefinition to retroactively invalidate the JPO's original findings.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment in the eAccess case brought important clarity to the procedural effects of divisional applications and amendments made during the course of litigation challenging a JPO trademark refusal decision. By ruling that such amendments do not have retroactive effect on the original application for the purposes of the JPO decision under review, the Court reinforced the principle of finality for administrative decisions and delineated the proper use of the divisional application system. While applicants can still use divisional applications to salvage rights for non-problematic parts of a broader application even after a refusal, they cannot use this mechanism to retroactively change the factual and legal basis upon which the JPO's original decision was made and is being judicially scrutinized. This decision mandates a disciplined approach to trademark prosecution and litigation, emphasizing the importance of addressing potential issues with the scope of an application while it is still under the JPO's purview if retroactive amendments are sought.