No Automatic Inheritance: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Succession to 'Improved Housing' Tenancy

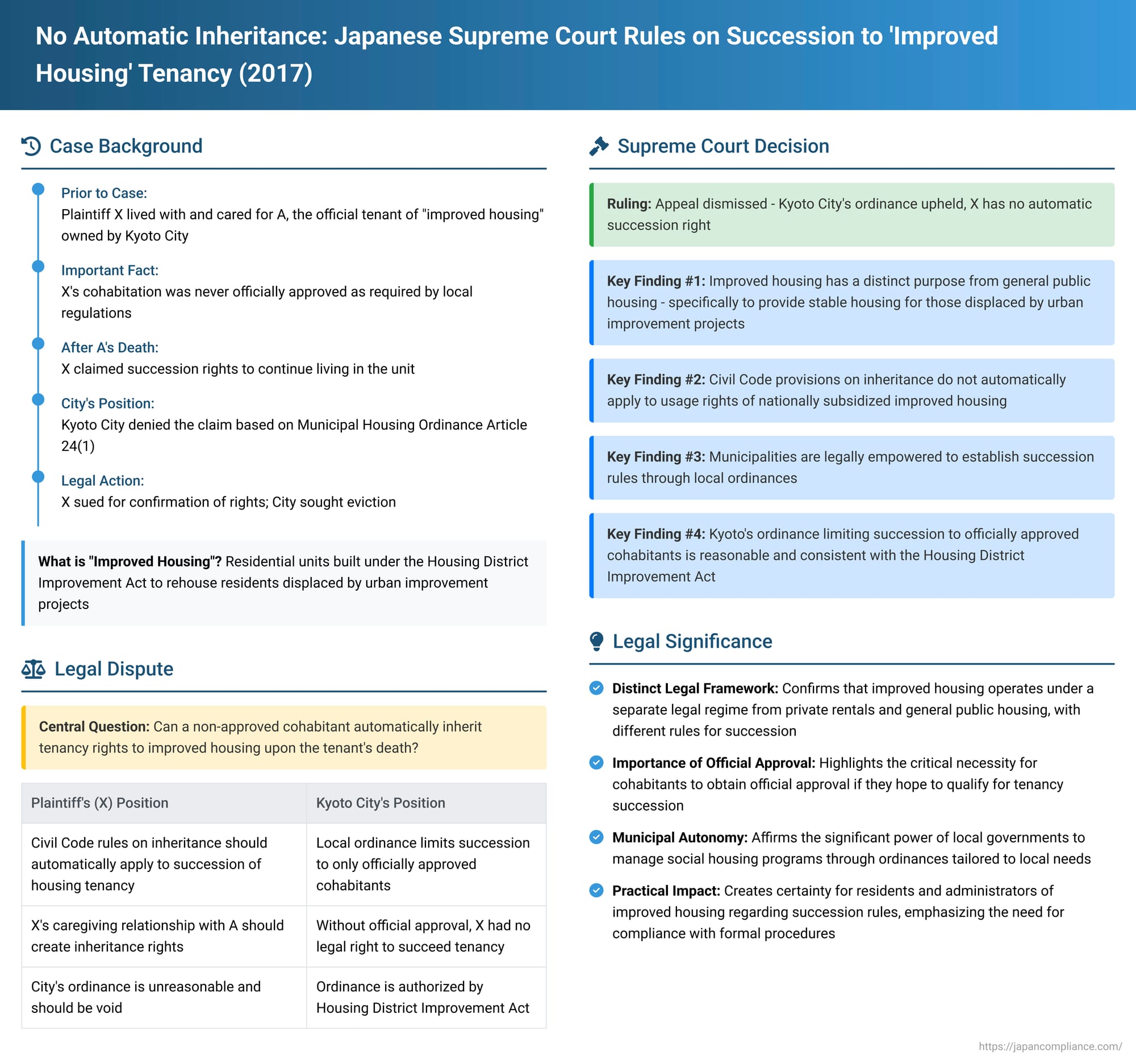

In Japan, "improved housing" (kairyō jūtaku) refers to residential units constructed under the Housing District Improvement Act, aimed at rehousing residents displaced by projects to upgrade areas with substandard dwellings. A critical question arises when an official tenant of such housing passes away: Who, if anyone, has the right to continue living there? Can family members or caregivers automatically inherit the tenancy, or can local government rules restrict such succession? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a definitive answer in a judgment on December 21, 2017 (Heisei 29 (Ju) No. 491), clarifying the legal status of these unique housing units.

The Case of the Caregiver and Kyoto City's Improved Housing

The case involved Plaintiff X, who had been living with and caring for A, the official tenant of an improved housing unit owned and managed by Defendant Y, the City of Kyoto. Importantly, X's cohabitation with A had not received official approval from the city as required by local regulations.

After A's death, X asserted a claim to have succeeded A's right to use the housing unit and sought legal confirmation of this right and the applicable rent. The City of Kyoto (Y) denied X's claim, arguing that X had no right to succeed the tenancy. The City based its position on Article 24, Paragraph 1 of its Municipal Housing Ordinance ("the Ordinance"). This Ordinance stipulated that if a tenant of improved housing died, only a person who was cohabiting with the tenant at the time of death and had been officially approved as a cohabitant (either at the time of initial tenancy or through subsequent approval) could apply for the Mayor's permission to continue residing in the unit. Since X was not an officially approved cohabitant, the City sought X's eviction and payment for unauthorized occupation.

The lower courts, including the Osaka High Court, had sided with Kyoto City, finding the Ordinance provision lawful and concluding that X had no right to succeed the tenancy. X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Framework: Housing District Improvement Act vs. General Inheritance

Understanding this case requires a look at the relevant laws:

- Housing District Improvement Act ("the Act"): This national law provides the framework for improving living conditions in areas with dilapidated housing. It obliges implementing bodies (typically municipalities) to construct "improved housing" and offer it to those displaced by such projects who are in housing distress.

- Publicly Operated Housing Act: While some provisions of this Act are applied to the management of nationally subsidized improved housing, a key provision (Article 27, Paragraph 6, concerning the succession rights of cohabitants in regular public housing) is not applied to improved housing under the Act. This distinction is crucial.

- Civil Code: In general private rental housing, the Civil Code's rules on inheritance would typically allow heirs to succeed to a tenancy.

- Municipal Ordinances: The Act (specifically Article 29, Paragraph 1, via Article 48 of the Publicly Operated Housing Act) authorizes and requires implementing bodies like Kyoto City to enact local ordinances to stipulate necessary matters concerning the management of improved housing. Kyoto City's Ordinance Article 24(1) was one such rule.

The Supreme Court's Decision (December 21, 2017): Ordinance Upheld, No Automatic Succession

The Supreme Court dismissed X's appeal, upholding the legality of Kyoto City's Ordinance and confirming that there is no automatic right of succession to improved housing tenancy through general inheritance rules.

The Court's reasoning unfolded as follows:

- Improved Housing is Distinct from General Public Housing: The Court emphasized that improved housing has a specific purpose: to provide stable housing for those who lose their homes due to urban improvement projects and are in housing distress. This differs from general publicly operated housing, which caters to a broader category of low-income individuals in housing need. The explicit non-application of certain succession rules from the Publicly Operated Housing Act to improved housing underscores this distinction.

- Right to Occupy Improved Housing is Not Compensation: The Court clarified that providing improved housing to displaced residents is not a form of compensation for their prior property rights (for which separate monetary compensation is provided under the Act). Rather, it is an obligation placed on the implementing body to ensure the housing stability of these specific individuals. This characterization influenced the Court's view on succession.

- No Automatic Civil Code Inheritance: Given the specific nature and purpose of improved housing, the Court concluded that "the provisions of the Civil Code concerning inheritance cannot be interpreted as automatically applying" to the succession of usage rights in nationally subsidized improved housing when a tenant dies.

- Ordinances Can Define Succession Rules: The Supreme Court affirmed that implementing bodies (municipalities) are empowered by the Act to establish rules for the management of improved housing, including rules on succession of usage rights, through local ordinances. This delegation is valid as long as the ordinances do not conflict with the provisions or the fundamental purpose of the Act.

- Kyoto City's Ordinance Deemed Lawful and Reasonable: The Court examined Kyoto City's Ordinance Article 24(1), which limited the possibility of continued residency to those who were officially approved cohabitants at the time of the original tenant's death (and then only with the Mayor's subsequent approval). The Court found this provision to be reasonable and consistent with the Act's objective of ensuring housing stability for the intended beneficiaries of housing improvement projects. By limiting succession to approved cohabitants, the Ordinance helps ensure that the housing continues to serve those for whom it was specifically built. The Court concluded that the Ordinance "cannot be said to be unreasonable in light of the provisions and purport of the Act" and was therefore not illegal or void.

Since Plaintiff X was not an officially approved cohabitant at the time of A's death, X could not claim succession rights under the valid Ordinance.

Key Takeaways and Differences from Other Housing Types

This Supreme Court decision has several important implications:

- Importance of Official Approval for Cohabitants: For individuals living with tenants in improved housing, especially caregivers or family members not part of the original household, this case highlights the critical importance of obtaining official approval for cohabitation from the municipal authority if they hope to have any chance of succeeding the tenancy. Informal arrangements are insufficient.

- Improved Housing is Not Private Rental: The automatic inheritance of tenancy rights commonly seen in private rental agreements under the Civil Code does not apply to this specific category of social housing.

- Distinct Rules from General Public Housing: While there are rules for cohabitant succession in some types of publicly operated housing, improved housing under the Housing District Improvement Act operates under a distinct legal framework where local ordinances play a decisive role in defining succession, and these can be more restrictive. The specific non-application of Publicly Operated Housing Act Art. 27(6) to improved housing was a key legal point for the Court.

The Role of Municipal Ordinances in Social Housing

The judgment reaffirms the significant power and responsibility vested in local governments to manage specific social housing programs like improved housing through ordinances. As long as these local rules are rational and consistent with the objectives of the national enabling legislation, they can establish particular criteria for tenancy, including the often sensitive issue of who may continue to live in a unit after the original tenant's death. The commentary suggests that many municipalities have ordinances similar to Kyoto City's.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2017 decision brings clarity to the often complex and emotionally charged issue of who can succeed to the usage rights of "improved housing" in Japan. It establishes that there is no automatic right of inheritance under general civil law. Instead, succession is governed by the specific provisions of the Housing District Improvement Act and, crucially, by the local municipal ordinances enacted thereunder. These ordinances can legitimately restrict succession to specific categories of individuals, such as officially approved cohabitants, in line with the unique purpose and targeted nature of this form of social housing. This ruling underscores the necessity for residents and their families in improved housing to be acutely aware of and comply with local regulations regarding cohabitation and succession.