No Afterthoughts in Discipline: Japan's Supreme Court on Adding Reasons Post-Dismissal (September 26, 1996)

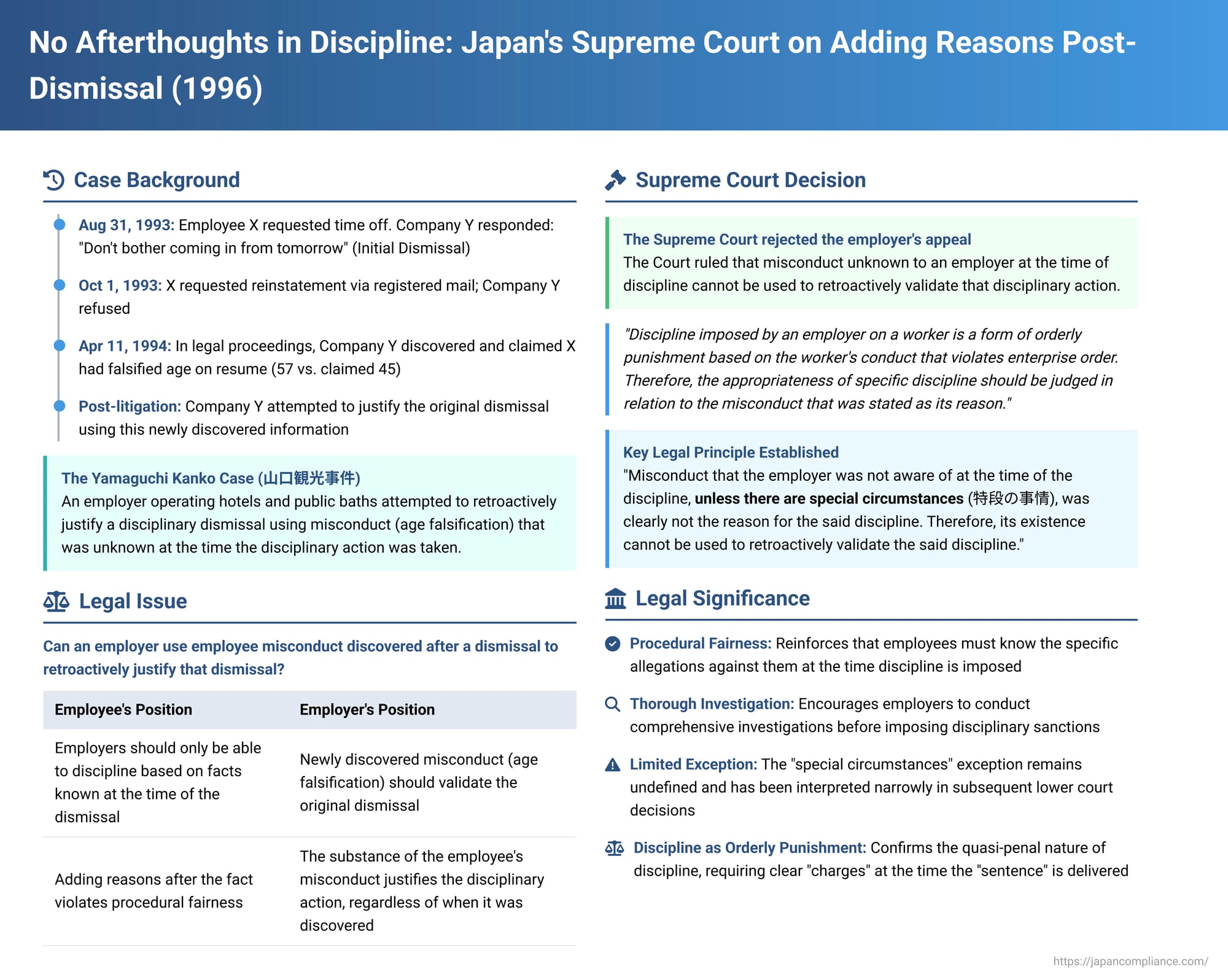

On September 26, 1996, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered an important judgment in a wage claim case, commonly known by commentators as the "Yamaguchi Kanko Case" (山口観光事件). This ruling addressed a critical procedural question in employment law: Can an employer, when defending the legality of a disciplinary action already taken against an employee, introduce and rely on new grounds of misconduct that the employer was not aware of at the time the original disciplinary sanction was imposed? The Court's decision significantly curtails an employer's ability to retroactively justify disciplinary actions with later-discovered facts.

The Factual Background: A Dismissal and a Later Revelation

The plaintiff, X, had been employed since 1991 in the massage business operated by Defendant Company Y, a company running hotels and public baths.

The sequence of events leading to the dispute was as follows:

- Leave Request and Initial Dismissal: On August 31, 1993, which was X’s scheduled day off, X contacted Company Y by telephone. Citing extreme exhaustion, X requested to take the following two days off. The representative of Company Y responded dismissively, stating, "We can't operate if you take days off as you please. We don't need someone like you anymore. You can resign. Don't bother coming in from tomorrow". This communication was treated by both parties as X's dismissal (referred to as the "Dismissal" or "initial Dismissal").

- Request for Reinstatement and Legal Action: On October 1, 1993, X formally requested reinstatement via registered mail but was refused. Consequently, X applied to the court for a provisional disposition to preserve employment status.

- Company Y's "Preliminary Dismissal" Based on New Grounds: In its written response to X’s application for a provisional disposition, dated April 11, 1994, Company Y introduced a new element. It stated that if the initial Dismissal of August 31, 1993 (which it had based on X's alleged refusal to report to work) was found to be invalid, then Company Y was, as a contingency, effecting a preliminary disciplinary dismissal (the "Preliminary Dismissal"). The grounds for this Preliminary Dismissal were that X had allegedly falsified information on the resume submitted at the time of hiring – specifically, X had stated an age of 45 when, in fact, X was 57 years old.

- The Main Lawsuit: The present case before the Supreme Court was the main lawsuit initiated by X seeking payment of unpaid wages following the initial Dismissal.

The Lower Courts' Handling of the Dismissals

- Osaka District Court (First Instance):

- The District Court found the initial Dismissal of August 31, 1993, to be invalid. It reasoned that X's actions regarding the leave request did not constitute a valid disciplinary ground such as "violating work-related instructions."

- Regarding the age falsification on X's resume (a misrepresentation of personal history - 経歴詐称, keireki sashō), the court noted that this was a fact discovered by Company Y after the initial Dismissal had already occurred and was not a reason cited by the company at that time. Therefore, this later-discovered misrepresentation could not be used to retroactively justify the initial Dismissal as a disciplinary dismissal. The court also found that treating the initial Dismissal as an ordinary dismissal based on this later-discovered fact would amount to an abuse of the right to dismiss.

- However, the District Court found the Preliminary Dismissal (which was explicitly based on the age falsification discovered prior to this specific declaration) to be a valid disciplinary dismissal. It determined that the age misrepresentation fell under a work rule provision allowing for disciplinary action if an employee "gained employment by falsifying important personal history or by other fraudulent means." The court found no abuse of disciplinary power in this instance.

- Consequently, the District Court ordered Company Y to pay X wages up to the date the valid Preliminary Dismissal took effect.

- Osaka High Court (Appeal): Both Plaintiff X and Company Y appealed the District Court's decision. The High Court largely agreed with the first instance judgment and dismissed both appeals.

Company Y then appealed to the Supreme Court. The central issue in this appeal was whether the High Court had erred in law by ruling that Company Y could not use the fact of X's age falsification (discovered after the initial Dismissal) as a reason to validate that initial Dismissal.

The Supreme Court's Key Ruling: No Retroactive Justification with Unknown Facts

The Supreme Court dismissed Company Y's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision on this critical point. The Supreme Court’s reasoning was clear and direct:

- Nature of Disciplinary Action: "Discipline imposed by an employer on a worker is a form of orderly punishment (秩序罰 - chitsujo batsu) based on the worker's conduct that violates enterprise order. Therefore, the appropriateness of specific discipline should be judged in relation to the misconduct that was stated as its reason."

- Misconduct Unknown at Time of Discipline: "Consequently, misconduct that the employer was not aware of at the time of the discipline, unless there are special circumstances (特段の事情 - tokudan no jijō), was clearly not the reason for the said discipline. Therefore, its existence cannot be used to retroactively validate the said discipline."

- Application to the Present Case: "Applying this to the present case, according to the facts lawfully established by the High Court, the disciplinary dismissal in question [the initial Dismissal of August 31, 1993] was effected for reasons such as X's request for leave and X's attitude during that interaction. At the time of this disciplinary dismissal, Company Y was not aware of the fact of X's age falsification. Therefore, the said age falsification cannot be used to validate this disciplinary dismissal."

The Supreme Court found the High Court's reasoning on this point to be correct and justifiable, and saw no error in its legal interpretation or conflict with existing precedents.

Deeper Dive: Rationale and Implications

This judgment by the Supreme Court was the first of its kind at the highest judicial level to explicitly adopt a restrictive stance against employers adding or substituting reasons for disciplinary action based on facts that were unknown to them when the discipline was originally imposed.

- The Punitive Nature of Discipline: The Court's reasoning stems from the understanding that disciplinary action is a form of "orderly punishment" (chitsujo batsu) imposed for specific violations of enterprise order. This quasi-penal nature implies that, much like in criminal law, the "charges" (i.e., the reasons for discipline) should be clear and known at the time the "sentence" (the disciplinary sanction) is delivered.

- The "Special Circumstances" Caveat: The Supreme Court did include a caveat: "unless there are special circumstances (tokudan no jijō)". However, the judgment itself does not elaborate on what might constitute such special circumstances. This has left room for interpretation in subsequent case law and academic discussion.

- The commentary suggests that later lower court cases have often explored this in the context of situations where the newly cited misconduct is "substantially identical, of the same type/category, or closely related" to the originally stated reason. This is particularly relevant for the "second type" of scenario, where the employer knew of other misconduct at the time of discipline but did not explicitly state it as a reason. The Fujimi Kotsu Case (Tokyo High Court, 2001) is cited as an example of this line of thinking.

- Some interpretations suggest "special circumstances" might cover situations like repeated, similar offenses (e.g., ongoing embezzlement) where the employer's disciplinary intent could reasonably be understood to encompass the entire pattern of behavior, including specific instances not yet fully discovered at the moment of initial action.

- Emphasis on Procedural Fairness and Due Process: Academic commentary largely supports the Supreme Court's restrictive approach, often grounding it in principles of procedural fairness and due process. The argument is that allowing an employer to later introduce new reasons for a disciplinary action, especially reasons unknown at the time, effectively deprives the employee of a meaningful opportunity to explain or defend themselves against those specific allegations before the sanction is imposed (this is often linked to the concept of 弁明の機会 - benmei no kikai, the opportunity for explanation or defense). Introducing new grounds later can be seen as an unfair "ambush" in legal proceedings.

- Distinction from New Disciplinary Actions or Ordinary Dismissals: It's important to distinguish the issue in this case—adding reasons to justify an existing disciplinary action—from an employer taking new disciplinary action or effecting an ordinary dismissal based on facts that have come to light subsequently. The latter involves a fresh decision-making process and is subject to its own set of legal requirements. The Yamaguchi Kanko case specifically addresses the retroactive justification of a past disciplinary act.

The Importance of Stated Reasons at the Time of Discipline

The Supreme Court's decision in the Tourism Company Y case reinforces several important principles for employers:

- Thorough Investigation Pre-Discipline: Employers should conduct a comprehensive investigation into alleged misconduct before imposing any disciplinary sanctions. Decisions should be based on the facts known at that time.

- Clear Articulation of Reasons: The specific misconduct forming the basis of the disciplinary action should be clearly communicated to the employee at the time the discipline is imposed. This ensures transparency and allows the employee to understand the charges against them.

- Discipline is Not a Moving Target: Once a disciplinary action is taken for specified reasons, the employer generally cannot "bolster" its justification by later introducing other, previously unknown, instances of misconduct by the employee.

Conclusion: Upholding Fairness in Disciplinary Procedures

The Supreme Court's judgment in the Yamaguchi Kanko (Tourism Company Y) case significantly clarifies the rules regarding the justification of disciplinary actions in Japan. By largely prohibiting employers from using after-acquired knowledge of employee misconduct to validate a prior disciplinary sanction, the Court underscored the importance of procedural fairness and the principle that discipline must be tied to the reasons known and articulated by the employer when the action was taken. While the narrow, undefined exception of "special circumstances" exists, the ruling sends a strong message that employers must be diligent in their investigations and clear in their reasoning at the moment discipline is imposed, rather than seeking to retroactively build a case based on later discoveries. This contributes to a more predictable and fair disciplinary process for employees.