Negative Equity on Exit: An Unlimited Partner's Duty to Pay a Deficit to a Japanese Limited Partnership – A Supreme Court Analysis

Judgment Date: December 24, 2019

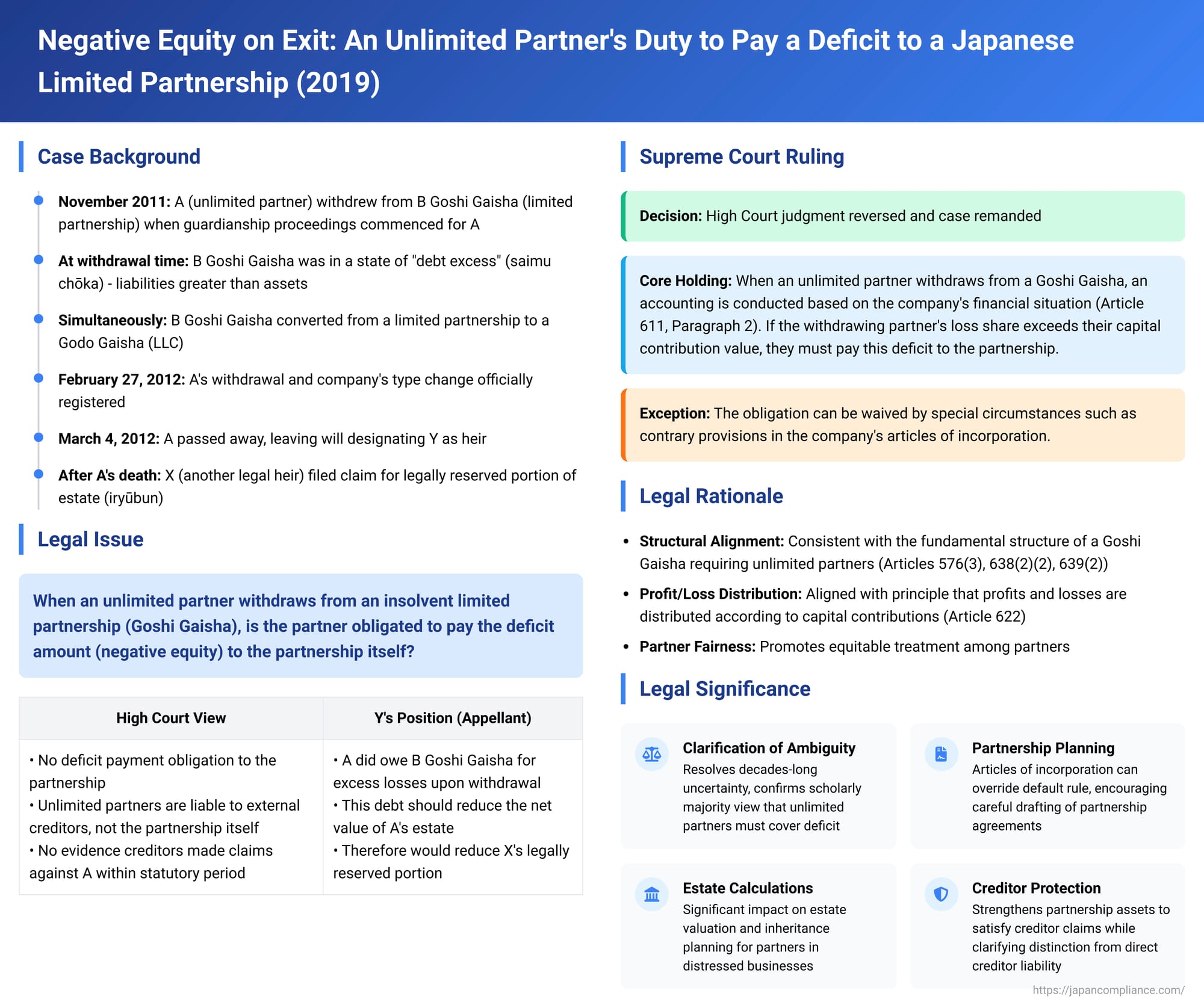

The Japanese Goshi Gaisha, or limited partnership, is a business structure characterized by the presence of two types of partners: those with unlimited liability for the company's debts and those with limited liability, typically restricted to the amount of their capital contribution. A critical question arises when an unlimited partner withdraws from such a partnership, particularly if the company is insolvent and the withdrawing partner's capital account (or "partnership interest") reflects a negative balance – meaning their share of the company's losses exceeds their capital contribution. Does this partner then owe the deficit amount back to the partnership itself? A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on December 24, 2019, addressed this very issue, providing significant clarification.

The Factual Backdrop: An Inheritance Case Hinges on Partnership Law

The case before the Supreme Court was an inheritance dispute, where the central issue necessary to determine the value of the deceased's estate revolved around this question of partnership liability.

The deceased, A, had been an unlimited partner in B Goshi Gaisha. In November 2011, A withdrew from B Goshi Gaisha. This withdrawal was not voluntary but occurred due to a statutory reason: the commencement of guardianship proceedings against A (as per Article 607, Paragraph 1, Item 7 of the Companies Act). At the time of A's withdrawal, B Goshi Gaisha was in a state of "debt excess" (saimu chōka), meaning its liabilities were greater than its assets.

Simultaneously with A's withdrawal, B Goshi Gaisha underwent a structural change, converting from a limited partnership to a Godo Gaisha (a Japanese company type akin to an LLC). The official registration of A's withdrawal and B Goshi Gaisha's change in company type were both completed on February 27, 2012. Shortly thereafter, on March 4, 2012, A passed away.

A had left a will stipulating that all of his property was to be inherited by Y (the defendant and appellant in the Supreme Court). X (the plaintiff and appellee), A's other legal heir, filed a claim for their legally reserved portion of the estate (iryūbun減殺請求 - iryūbun gensai seikyū). To accurately calculate the value of A's estate, and thus X's reserved share, it was essential to determine all of A's assets and liabilities. The pivotal contested liability was whether A, upon his withdrawal from the insolvent B Goshi Gaisha, incurred a debt to B Goshi Gaisha for the amount by which his share of the company's losses exceeded his capital contribution.

The Lower Court's Position: No Debt Owed to the Partnership for Negative Equity

The High Court (Nagoya High Court) had ruled that A did not owe such a "loss excess payment obligation" (損失超過額支払債務 - sonshitsu chōkagaku shiharai gimu) to B Goshi Gaisha. The High Court's reasoning was primarily that while partners, especially unlimited ones, are liable for the partnership's debts (under provisions like Article 580, Paragraph 1, Item 1 of the Companies Act), this liability is owed to the company's external creditors, not to the company itself as a consequence of an internal negative equity balance.

Furthermore, the High Court considered the liability of a withdrawn partner for pre-withdrawal company debts to external creditors (governed by Article 612, Paragraph 1 of the Companies Act). It found no evidence that B Goshi Gaisha's creditors had made any claims against A (or his estate) within the statutory two-year period following the registration of A's withdrawal, suggesting that A's liability to those creditors had likely extinguished.

Y, wishing to reduce the net value of A's estate by including this alleged debt, appealed this part of the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court, contending that A did indeed owe B Goshi Gaisha for the excess losses upon withdrawal.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision

The Supreme Court, on December 24, 2019, reversed the High Court's judgment on this specific point and remanded the case for further proceedings.

The Supreme Court laid down the following core holding:

When an unlimited partner withdraws from a Goshi Gaisha, an accounting is conducted based on the company's financial situation at the time of withdrawal (as per Article 611, Paragraph 2 of the Companies Act). If, as a result of this accounting, the amount of loss to be borne by the withdrawing partner is less than the value of that partner's capital contribution (i.e., the partner has a positive equity interest), the partner is entitled to a refund of their partnership interest (Article 611, Paragraph 1).

However, if the accounting reveals that the amount of loss to be borne by the withdrawing partner exceeds the value of that partner's capital contribution (i.e., the partner has a negative equity interest or deficit), then, absent special circumstances such as a contrary provision in the company's articles of incorporation, the withdrawing unlimited partner is obligated to pay this excess amount (the deficit) to the partnership.

The Supreme Court provided two main justifications for this interpretation:

- Alignment with the Goshi Gaisha System: This interpretation is consistent with the fundamental structure and mechanisms of a Goshi Gaisha. The Court pointed to several statutory provisions underpinning this:

- The requirement that unlimited partners must exist for the formation and continued existence of a Goshi Gaisha (Companies Act Articles 576, Paragraph 3; 638, Paragraph 2, Item 2; and 639, Paragraph 2).

- The principle that profits and losses are distributed among partners according to their capital contributions or other agreed-upon ratios (Companies Act Article 622).

- Fairness Among Partners: The Court stated that this interpretation also accords with fairness among the partners of the Goshi Gaisha.

Applying this to A's situation, the Supreme Court noted that since B Goshi Gaisha was in a state of debt excess when A, an unlimited partner, withdrew, if the withdrawal accounting determined that A's share of the company's losses exceeded A's capital contribution, then A (and consequently, his estate) would be liable to pay this deficit to B Goshi Gaisha, unless special circumstances, such as a specific provision in the articles of incorporation, dictated otherwise.

The case was remanded to the High Court to re-examine whether A owed such a debt to B Goshi Gaisha and to recalculate X's legally reserved share of A's estate accordingly.

Unpacking the Legal Principles

This Supreme Court decision clarifies a significant aspect of partnership law, particularly the responsibilities of unlimited partners.

- Accounting Upon Withdrawal (Article 611): The Companies Act mandates an accounting process when a partner withdraws. This process determines the value of the partner's "interest" or "share" (mochibun) in the company. This share generally reflects the partner's past capital contributions adjusted by their allocated portion of the company's accumulated profits and losses.

- The Nature of the "Deficit Payment Obligation": The obligation identified by the Supreme Court is a debt owed by the withdrawing unlimited partner directly to the partnership. This payment would bolster the partnership's assets, enabling it to better satisfy its own external creditors. This is distinct from the partner's direct liability to those external creditors.

- "Special Circumstances" – The Articles of Incorporation Exception: The Supreme Court explicitly allows for the articles of incorporation of the Goshi Gaisha to provide otherwise. This means a partnership could, in its foundational document, choose to waive or modify this obligation for withdrawing unlimited partners to pay a deficit. Legal commentary suggests this reflects a view that the direct liability of the unlimited partner to company creditors (under Article 612) might be considered sufficient protection for those creditors in certain contexts, allowing the partnership internal flexibility. For example, when an unlimited partner changes status to become a limited partner, their liability for future contributions to cover company losses can be internally adjusted by amending the articles, while creditors retain their direct claims for past debts.

Analysis and Implications

This 2019 judgment has several important implications:

- Clarification of an Ambiguity: Prior to this decision, while a Daishin-in case from 1918 (Taisho 7.12.7) was often interpreted as supporting the view that a withdrawing partner with negative equity owed the company, some commentators argued that the older case might have specifically concerned an unfulfilled capital contribution rather than a net deficit arising from losses. The prevailing scholarly view, however, was that unlimited partners should indeed cover such deficits. This Supreme Court decision provides clear, high-level judicial confirmation.

- Interaction with Direct Liability to Creditors (Article 612): A key point of discussion is how this obligation to the partnership interacts with the withdrawing unlimited partner's ongoing direct liability to the company's creditors for debts incurred before their withdrawal was registered (as per Article 612, Paragraph 1). Some critics of the ruling raise a "double liability" concern: if the partner pays the deficit to the company, and the company (or remaining partners) subsequently becomes insolvent, the withdrawn partner might still be pursued by creditors for the same underlying company debts, effectively paying twice or bearing the insolvency risk of the ongoing enterprise.

However, as legal commentary points out, this risk is somewhat inherent to the status of an unlimited partner. Even a partner who withdraws with positive equity and receives a refund could later be called upon by creditors under Article 612 if the company subsequently fails. The legal framework for Goshi Gaisha appears to presuppose that unlimited partners accept a degree of risk related to the company's (and other partners') solvency. - The "Fairness Among Partners" Rationale: The Supreme Court mentioned that requiring the withdrawing unlimited partner to pay the deficit is "fair among partners." The concept of "fairness" can be subjective. Some might argue that only requiring the fulfillment of any unpaid capital contributions would be a fairer standard, especially when considering the differing positions of unlimited and limited partners. However, the Court's use of "fairness" might be interpreted as alignment with the typical, reasonable expectations and implied understanding among partners entering into a Goshi Gaisha structure, which relies heavily on the financial backing of its unlimited partners.

- Permissive Nature of the Obligation: The Court's reasoning for the deficit payment obligation refers to mandatory statutory provisions about the essential role of unlimited partners in a Goshi Gaisha (e.g., Articles 576(3), 638(2)(2)). Yet, its conclusion is that the obligation itself is permissive, meaning it can be waived by the articles of incorporation. This apparent tension might be resolved if one understands the Court to be inferring the "ordinary intent" or default understanding of partners from these structural, mandatory rules. If partners wish to deviate from this default, they can explicitly do so in their articles.

- Scope of the Ruling:

- Applicability when other unlimited partners remain: The facts of this case involved the withdrawal of an unlimited partner (A) and a simultaneous change in the company's type from a Goshi Gaisha to a Godo Gaisha, which might imply A was the sole or one of the last remaining unlimited partners whose withdrawal necessitated the change. Does the ruling apply with equal force if an unlimited partner withdraws but other unlimited partners remain, and the company continues as a Goshi Gaisha? Legal commentary suggests that from the perspective of internal profit and loss allocation among partners, the principle should still hold: the withdrawing unlimited partner should generally be liable to the company for their share of excess losses.

- Limited Partners: This judgment is specifically about the obligations of a withdrawing unlimited partner. It does not address the situation of a withdrawing limited partner. The widely held scholarly view is that limited partners, whose liability is generally capped at their contribution amount, are not obligated to pay any deficit to the company if their share becomes negative due to losses.

- Significance for Estate Planning and Valuation: As this case illustrates, the existence of such a debt owed by a deceased former unlimited partner to the partnership can significantly affect the net value of their estate, impacting the distribution among heirs and the calculation of legally reserved shares.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's December 2019 decision provides crucial clarity on a previously somewhat ambiguous area of Japanese partnership law. It establishes a default rule that withdrawing unlimited partners from a Goshi Gaisha are indeed liable to the partnership for any deficit in their capital account arising from an excess of losses over their contributions. This reinforces the fundamental role and responsibility of unlimited partners in covering the financial shortfalls of the partnership. However, the ruling also provides flexibility, allowing partners to modify this default rule through specific provisions in their articles of incorporation. This judgment has important practical consequences for the structuring of partnership agreements, the management of partner withdrawals, and the valuation of a partner's assets and liabilities, especially in the context of estate settlement.