Navigating Wrongful Dismissal: The Akebono Taxi Case and Interim Income Deduction in Japan

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Judgment of April 2, 1987 (Case No. 1984 (O) No. 84: Claim for Confirmation of Employment Relationship, etc.)

Appellants: A Company

Appellees: X1 and X2

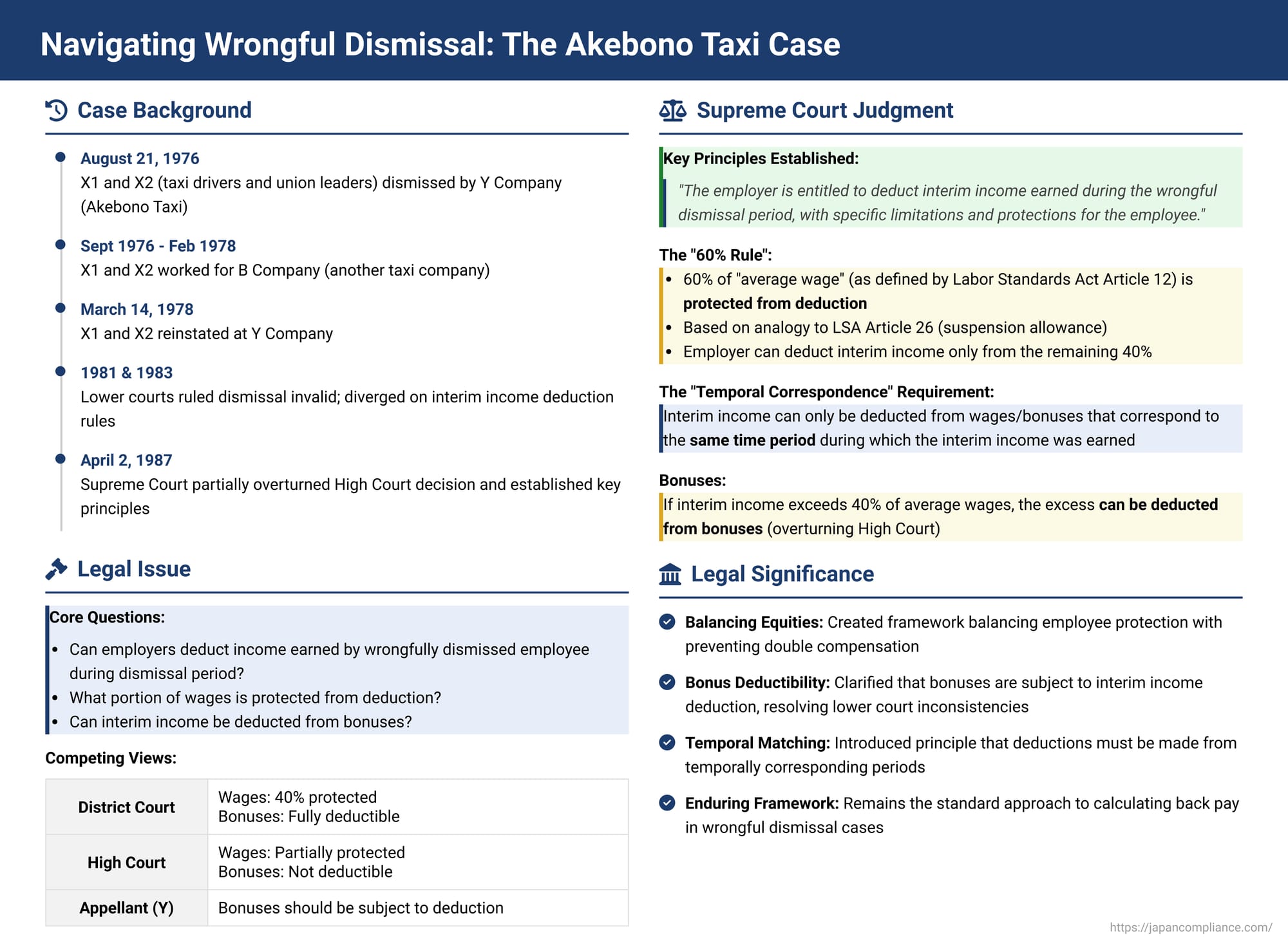

This case, often referred to as the Akebono Taxi case, is a pivotal decision by the Supreme Court of Japan that significantly clarified the rules surrounding the payment of wages for a period of wrongful dismissal and, crucially, how an employer can deduct income earned by the employee from another job during that period (interim income). The judgment of April 2, 1987, delves into the interplay between the Civil Code, the Labor Standards Act (LSA), and principles of fairness in resolving such disputes.

Background of the Dispute

The plaintiffs, X1 and X2, were taxi drivers employed by Y Company, a passenger transportation business. X1 held the position of executive committee chairman of a labor union (not affiliated with the main lawsuit parties), while X2 served as the secretary-general of the same union.

On August 21, 1976, Y Company dismissed both X1 and X2 through disciplinary action, citing reasons such as distributing flyers and unsatisfactory work performance. This dismissal was referred to as "the present dismissal."

Believing their dismissal to be invalid, X1 and X2 initiated legal proceedings against Y Company. They sought:

- Confirmation of their existing rights under their employment contracts.

- Payment of wages for the period they were unable to work due to the dismissal.

It is noteworthy that after their dismissal from Y Company, X1 and X2 found alternative employment. From September 1, 1976, to February 10, 1978, they worked as taxi drivers for B Company and earned income during this period. They were subsequently reinstated at Y Company on March 14, 1978.

Lower Court Rulings

The Court of First Instance (Fukuoka District Court, March 31, 1981):

The District Court ruled in favor of X1 and X2, finding that the dismissal constituted an unfair labor practice and was therefore invalid. Consequently, the court recognized their entitlement to wages and bonuses for the period of non-employment resulting from the wrongful dismissal.

However, the court also permitted Y Company to deduct the interim income earned at B Company from the owed wages and bonuses. The scope of this deduction was specified:

- For regular wages, the deduction was limited to an amount equivalent to 40% of the average wage.

- For bonuses, the entirety of the interim income could be deducted.

The Appellate Court (Fukuoka High Court, October 31, 1983):

The High Court upheld the District Court's finding that the dismissal was invalid. However, it diverged on the issue of interim income deduction. The High Court stipulated that deductions could only be made from wages that form the basis for calculating "average wages" as prescribed by Article 12 of the Labor Standards Act. Bonuses, which are not included in the calculation basis for average wages under the LSA, were deemed non-deductible.

Dissatisfied with this aspect of the ruling, particularly the exclusion of bonuses from the scope of deduction, Y Company appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (April 2, 1987)

The Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's decision and remanded parts of the case, while dismissing other aspects of the appeal.

1. Invalidity of the Dismissal:

The Supreme Court affirmed the lower courts' determination that the dismissal of X1 and X2 constituted an unfair labor practice under Article 7, item 1 of the Labor Union Act, rendering it null and void. The Court found no errors in the High Court's fact-finding or application of the law in this regard.

2. Deduction of Interim Income from Wages and Bonuses:

This was the core issue addressed by the Supreme Court, leading to a significant clarification of legal principles.

- General Principle of Interim Income Deduction:

The Court began by stating a general principle: When an employee is dismissed due to reasons attributable to the employer and subsequently earns income (referred to as "interim benefit" or "interim income") from other employment during the dismissal period, the employer is entitled to deduct the amount of this interim benefit when paying wages for the dismissal period. This is rooted in Article 536, paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, which essentially states that if a party (debtor, here the employee) is prevented from fulfilling an obligation (work) due to the fault of the other party (creditor, here the employer), the creditor cannot refuse their own counter-performance (wage payment). However, if the debtor gains a benefit by being excused from their obligation, they must reimburse this benefit to the creditor. - Protection of a Portion of Wages (The 60% Rule):

The Court referenced its own precedent (Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, July 20, 1962 - the K-M Y Unit Case). This precedent established that, when deducting interim income, the portion of the owed wages that amounts to 60% of the "average wage" (as defined in Article 12, paragraph 1 of the Labor Standards Act) is protected from deduction. In other words, the employer must pay at least 60% of the average wage for the dismissal period, regardless of interim earnings. This protection is linked to Article 26 of the LSA, which mandates that an employer pay an allowance of at least 60% of the average wage if work is suspended for reasons attributable to the employer. The Court interpreted this not just as a requirement for suspension allowance but as a floor for payment even in wrongful dismissal cases where interim income is a factor. - Deduction from Wages Exceeding the Protected Portion:

Therefore, the employer can deduct interim income from the portion of the wage debt that exceeds 60% of the average wage. - Crucial Clarification on Bonuses and Other Payments:

The Supreme Court then addressed the High Court's contention that bonuses were entirely non-deductible. It ruled that if the amount of interim benefit (interim income) exceeds 40% of the average wage (i.e., the portion of regular wages that can be offset), then the employer is permitted to deduct this excess from the entirety of other wages that are not included in the calculation basis for average wages. This specifically includes payments like bonuses (which Article 12, paragraph 4 of the LSA excludes from the average wage calculation basis).

This was a direct refutation of the High Court's interpretation. The Supreme Court reasoned that the LSA's 60% average wage protection ensures a minimum living standard. However, for income beyond this, including bonuses, the principle from the Civil Code (reimbursing benefits gained) applies. - The "Temporal Correspondence" Requirement:

A highly significant and novel aspect of this judgment was the introduction of a "temporal correspondence" requirement. The Court stipulated:

"Interim benefits that can be deducted from wages must be limited to those benefits that arose during a period that temporally corresponds to the period for which said wages are being paid. It is not permissible to deduct benefits earned in a period that is temporally different from the period covered by the wage payment."

This means there must be a temporal alignment between the earning of the interim income and the wage period from which it's being deducted. One cannot, for instance, deduct a lump sum earned by the employee at a specific point from wages accrued over a much broader, or entirely different, timeframe without considering this correspondence. - Application to the Bonuses in this Case:

Based on these principles, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had erred in its interpretation of the law by ruling that the bonuses in question were entirely exempt from the deduction of interim income. This error in legal interpretation was deemed to have affected the judgment.

Therefore, the part of the High Court's decision that affirmed X1 and X2's claims for bonuses (specifically, the amounts exceeding 1,458,044 yen for X1 and 1,452,105 yen for X2) was quashed. - Remand for Re-examination:

The case was remanded to the Fukuoka High Court concerning the bonus payments. The Supreme Court instructed the High Court to re-examine the winter 1976 bonus, summer 1977 bonus, winter 1977 bonus, and summer 1978 bonus. The High Court was tasked with determining whether, after deducting the amount of interim benefits earned by X1 and X2 during periods temporally corresponding to the respective bonus calculation periods, any remaining bonus amount was due.

Significance and Implications of the Supreme Court's Decision

The Akebono Taxi judgment carries substantial weight in Japanese labor law for several reasons:

- Affirmation and Elaboration of Interim Income Deduction Rules: The decision reaffirmed the existing framework for deducting interim income, primarily based on the 1962 K-M Y Unit Case. This framework seeks to balance the employer's obligation to pay wages for a wrongful dismissal (as if the employment continued) with the principle that the employee should not receive a windfall by retaining both full back pay and interim earnings for the same period of relieved labor. The Civil Code's Article 536, paragraph 2, provides the underlying rationale, while LSA Article 26 (regarding休業手当 - leave allowance) is used to establish the 60% protected portion of average wages.

- Definitive Stance on Bonuses: This was arguably the most impactful element of the judgment. Lower court decisions had been inconsistent on whether bonuses could be subject to interim income deduction. The Supreme Court provided a clear answer: bonuses are subject to deduction, but only after the interim income has first offset the non-protected portion (up to 40%) of the average wage. If interim income still remains after this, then the full amount of the bonus can be targeted for deduction. This recognized that bonuses, while not part of the "average wage" calculation for LSA purposes, are still part of the remuneration an employee would have received had the dismissal not occurred, and thus fall under the Civil Code principle of reimbursing benefits.

- Introduction of the "Temporal Correspondence" Requirement: This was a novel and crucial development. By requiring that the interim income and the wage/bonus payment period align temporally, the Court aimed for a more equitable and precise calculation. It prevents potentially unfair situations where, for example, an employee's substantial but short-term interim earnings could be used to offset wages owed over a much longer period, or vice-versa. This principle mandates a more granular examination of when the interim income was earned relative to the specific wage or bonus periods in question.

- Practical Application and Subsequent Interpretation: The "temporal correspondence" principle, while sound, required further interpretation in practice. The way the remanded High Court handled this offers insight.

- The Remanded High Court Decision (Fukuoka High Court, October 26, 1988): When re-evaluating the bonuses, the remanded High Court meticulously applied the temporal correspondence rule. For example, concerning the winter 1976 bonus, which had a calculation period from June 1, 1976, to November 30, 1976 (183 days):

- The period from June 1, 1976, to August 31, 1976 (92 days) was before X1 and X2 started working at B Company (they started on September 1, 1976). Therefore, the portion of the bonus attributable to these 92 days could not have interim income deducted from it, as no interim income was earned that temporally corresponded to this specific part of the bonus calculation period.

- The portion of the bonus attributable to the remaining 91 days (from September 1 to November 30), during which they were earning interim income at B Company, was subject to deduction.

- A similar approach was taken for the summer 1978 bonus, exempting the portion corresponding to the period after they left B Company but before their reinstatement at Y Company. The remanded court essentially interpreted "temporally corresponding" by aligning the period of interim employment (on a daily basis) with the specific calculation period of each bonus.

- The Remanded High Court Decision (Fukuoka High Court, October 26, 1988): When re-evaluating the bonuses, the remanded High Court meticulously applied the temporal correspondence rule. For example, concerning the winter 1976 bonus, which had a calculation period from June 1, 1976, to November 30, 1976 (183 days):

- Ongoing Discussion and Scholarly Views: The Supreme Court's approach, particularly its interpretation of LSA Article 26 to justify the 60% protection, has been described by some scholars as a "creative interpretation" designed to provide a clear and practically manageable standard for a complex legal issue. It attempts to reconcile the Civil Code's principles of risk and benefit with the protective aims of the Labor Standards Act, especially the principle of full wage payment (LSA Article 24, paragraph 1, though exceptions exist).

However, critiques exist. Some argue that applying general Civil Code principles meant for ordinary contractual defaults to wrongful dismissal cases (which often involve employer misconduct like unfair labor practices) is inappropriate. Alternative views suggest there's no direct causal link between being relieved of the duty to work (due to wrongful dismissal) and the earning of interim income, or that an employer who wrongfully dismissed an employee should not, in good faith, be able to claim a deduction of income the employee was forced to seek elsewhere.

Furthermore, the exclusion of bonuses from the "average wage" calculation (LSA Article 12, paragraph 4) can itself be problematic. If bonuses constitute a significant portion of an employee's total compensation, the 60% protection based solely on the "average wage" might result in the employee receiving substantially less than 60% of their actual expected earnings during the dismissal period. The Akebono Taxi ruling, while clarifying bonus deductibility, operates within this existing LSA framework.

Conclusion

The Akebono Taxi Supreme Court judgment of April 2, 1987, remains a landmark in Japanese labor law. It solidified the rules for deducting interim income earned by wrongfully dismissed employees, notably extending these rules clearly to bonuses. Perhaps its most enduring contribution is the introduction of the "temporal correspondence" requirement, which insists on a fair and logical alignment between the timing of interim earnings and the wage or bonus periods from which they are deducted. This decision continues to guide how courts and practitioners navigate the financial remedies in cases of wrongful dismissal, striving for an equitable resolution between the employer's obligations and the employee's mitigated losses.