Navigating Wage Claims for Non-Strikers: The Northwest Airlines Case (Supreme Court of Japan, July 17, 1987)

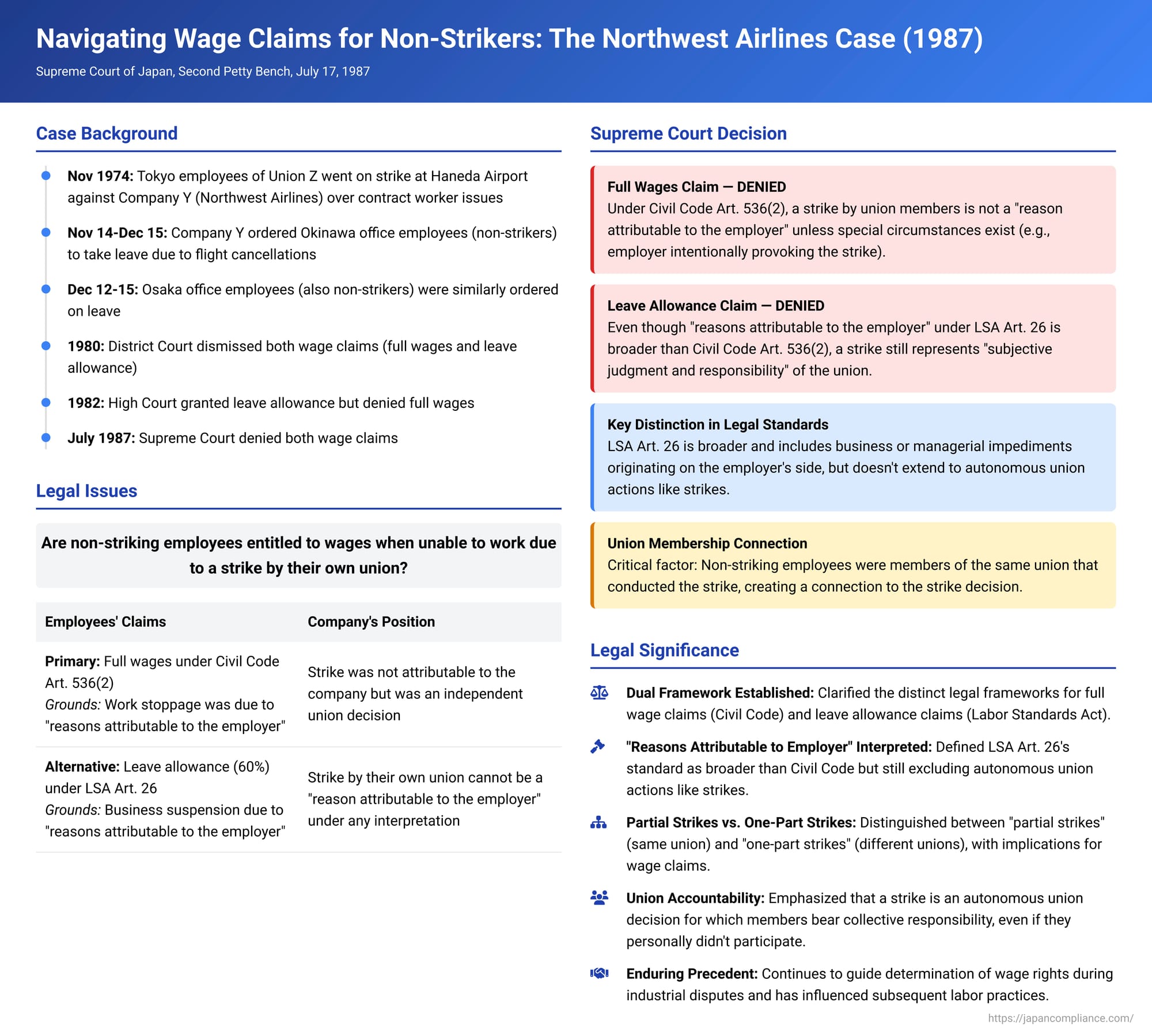

On July 17, 1987, the Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a significant judgment in what is commonly known as the Northwest Airlines case. This case addressed crucial questions regarding the wage rights of employees who, though not participating in a strike themselves, were unable to work due to a strike conducted by other members of their own union. The ruling clarified the distinction between claims for full wages under the Civil Code and claims for statutory allowance for business suspension (leave allowance) under the Labor Standards Act (LSA), and it provided a detailed interpretation of "reasons attributable to the employer" in such contexts.

Case References: 1982 (O) No. 1189 & 1190 (Wage Claim Case)

Appellant in No. 1189 / Appellee in No. 1190 (Original Defendant): Company Y (Northwest Airlines, Inc.)

Appellees in No. 1189 / Appellants in No. 1190 (Original Plaintiffs): Mr. X et al. (Yoshiharu Iha and 16 others)

Judgment of the Supreme Court:

- Regarding the employees' appeal (No. 1190, for full wages): Appeal dismissed (upholding denial of full wages).

- Regarding the company's appeal (No. 1189, against leave allowance): Original judgment (High Court's award of leave allowance) overturned; employees' appeal at the High Court stage dismissed (denying leave allowance).

This effectively meant that the employees' claims for both full wages and statutory leave allowance were ultimately rejected.

The Factual Landscape: A Strike's Ripple Effect

The dispute arose under the following circumstances:

- The Parties: Company Y was a U.S.-based airline operating internationally, with offices in Japan, including Tokyo, Osaka, and Okinawa. Mr. X et al. (the plaintiffs) were employees of Company Y working at its Osaka or Okinawa offices and were members of Union Z, the labor union representing Company Y's Japan branch employees.

- The Underlying Labor Dispute: In 1974, Union Z was in conflict with Company Y over the company's use of external contract workers (from J Service Company) for ground services at Tokyo's Haneda Airport. Union Z contended that this practice violated Article 44 of the Employment Security Act (concerning the prohibition of labor supply businesses). Demands included regularizing the contract ground hostesses and halting the subcontracting of loading operations.

- The Strike in Tokyo: Company Y proposed countermeasures, including a plan to integrate all loading staff into one group, which it claimed would resolve the alleged Employment Security Act violations. Union Z, however, found these proposals insufficient and, to prevent their implementation, initiated a strike from November 1, 1974, involving its members in the Tokyo (Haneda) district. This strike included the occupation of Company Y's ground equipment at Haneda Airport and continued until December 15, 1974.

- Impact on Flight Operations and Non-Striking Employees: Due to the difficulty in conducting ground operations at Haneda Airport caused by the strike, Company Y was forced to reduce the number of flights transiting Japan and alter routes.

- Flights via Okinawa ceased entirely from November 12, 1974. Consequently, Company Y ordered its employees in the Okinawa office (part of Mr. X et al.) to be on leave from November 14 to December 15, 1974, as their work was deemed unnecessary.

- Flights via Osaka also ceased from December 12, 1974. As a result, employees in the Osaka office (the remaining Mr. X et al.) were ordered on leave from December 12 to December 15, 1974.

- The Lawsuit: As Mr. X et al. were not paid their wages for these periods of mandated leave, they filed a lawsuit. Their primary claim was for full wages for the leave period. Alternatively, they sought the payment of statutory allowance for business suspension (leave allowance) as provided under Article 26 of the Labor Standards Act.

Procedural Journey

- The District Court (Tokyo District Court, judgment February 18, 1980) dismissed all of Mr. X et al.'s claims.

- The High Court (Tokyo High Court, judgment July 19, 1982) partially ruled in favor of Mr. X et al., granting their claim for statutory leave allowance under LSA Article 26, but denying their primary claim for full wages.

Both parties appealed to the Supreme Court: Mr. X et al. contested the denial of their full wage claim, and Company Y contested the award of the statutory leave allowance.

The Supreme Court's Adjudication

The Supreme Court addressed the employees' appeal for full wages and the company's appeal against the statutory leave allowance separately.

1. Employees' Appeal for Full Wages (Case No. 1190)

The Court dismissed the employees' appeal, upholding the denial of their claim for full wages. Its reasoning centered on the principles of risk allocation in bilateral contracts under Article 536, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Civil Code.

- Framework for Non-Performance: The Court stated that when employees who did not participate in a strike are unable to perform their labor obligations because work has become impossible or valueless from a societal perspective due to a strike by other employees, the question of whether the non-participating employees retain their wage claim rights should be examined as a matter of risk allocation under their individual employment contracts, assuming they had the will to work.

- Attribution of Cause for Strike-Induced Stoppage:

- A strike is an exercise of the right to dispute, guaranteed to workers. Employers cannot intervene in or control the decision to strike.

- The employer is free to decide what response to give to union demands and to what extent to concede during collective bargaining. Therefore, if negotiations break down and a strike ensues, this outcome cannot generally be considered attributable to the employer.

- Consequently, when a strike by a portion of employees renders it impossible for non-striking employees to perform their labor obligations, the non-striking employees lose their right to claim wages, unless special circumstances exist, such as the employer instigating the strike with the intent of committing an unfair labor practice or for other improper motives. Such a strike, absent these special circumstances, does not fall under "reasons attributable to the creditor (employer)" as stipulated in Article 536, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code.

- Application to the Facts: In this specific case, the Court found no such special circumstances. The inability of Mr. X et al. to work during the leave period was a consequence of the strike by their fellow union members in Tokyo. Therefore, this inability to perform work was not due to reasons attributable to Company Y under the Civil Code. As such, Mr. X et al. did not possess the right to claim full wages for this period.

2. Company's Appeal Against Statutory Leave Allowance (Case No. 1189)

The Court upheld the company's appeal, thereby overturning the High Court's decision to award statutory leave allowance under LSA Article 26.

- Nature of LSA Article 26 and its Relation to Civil Code Article 536(2):

- LSA Article 26 mandates that an employer pay an allowance of at least 60% of the average wage in case of a business suspension due to "reasons attributable to the employer." This provision aims to guarantee workers' livelihood to that extent.

- Importantly, LSA Article 26 does not exclude the application of Civil Code Article 536, Paragraph 2. If the cause of the suspension falls under "reasons attributable to the creditor (employer)" per the Civil Code, and the worker does not lose their full wage claim, then the claim for leave allowance and the claim for full wages can co-exist (though, in practice, the worker would pursue the more favorable claim).

- Interpretation of "Reasons Attributable to the Employer" (LSA Art. 26):

- The Court emphasized that interpreting "reasons attributable to the employer" under LSA Article 26 requires consideration of what grounds for suspension make it socially just to demand that the employer bear this level of burden for the protection of workers' livelihoods.

- Viewed this way, this phrase under LSA Article 26 is a concept that incorporates perspectives different from the general principle of fault-based liability found in contract law (as in Civil Code Art. 536(2)). It is broader than "reasons attributable to the creditor" under the Civil Code and includes business or managerial impediments originating on the employer's side.

- Application to the Facts of this Case:

- The High Court had found Company Y at fault for the occurrence of the strike, citing its alleged prior violations of the Employment Security Act and its failure to resolve the strike earlier by properly explaining its new operational plans to the union.

- The Supreme Court disagreed with the High Court's assessment. While acknowledging that Company Y's previous handling of contract workers might have contributed to the strike's origins, the Supreme Court noted that Company Y had made proposals to address the union's concerns, including plans to regularize some contract workers and restructure operations to comply with the Employment Security Act. The Court viewed Company Y's explanations for these plans as a "valid viewpoint."

- Against this backdrop, Union Z, holding a different view, decided to strike to achieve its demands, occupying company equipment and forcing a significant alteration of flight schedules. The Supreme Court concluded that this strike should be seen as an action undertaken based solely on the subjective judgment and responsibility of Union Z, to which Mr. X et al. belonged. Therefore, the strike was not an event attributable to Company Y. The company's alleged failure to explain a subsequent contract with J Service Company to the union did not alter this conclusion.

- Since the flights through Osaka and Okinawa were almost entirely eliminated during the mandated leave period, making the labor of Mr. X et al. valueless from a societal perspective, the resulting leave ordered by Company Y could not be considered a business or managerial impediment originating on Company Y's side.

- Thus, the leave was not due to "reasons attributable to the employer" under LSA Article 26, and Mr. X et al. could not claim the statutory leave allowance.

Analysis and Significance

The Northwest Airlines judgment is a landmark decision providing critical clarification on how Japanese labor law addresses the wage rights of employees who are idled due to strikes they do not directly participate in, especially when the strike is by their own union.

- Dual Framework for Wage and Allowance Claims: The decision firmly establishes two distinct legal frameworks:

- Full Wage Claims: Governed by the Civil Code's risk allocation principles (Art. 536(2)). The employer is liable for full wages only if the work stoppage is due to reasons specifically attributable to the employer's fault or equivalent circumstances. A strike by a union, being an independent action of the union, generally does not meet this criterion, even for non-striking members of that union.

- Statutory Leave Allowance Claims (LSA Art. 26): This provision has a worker protection purpose and uses a broader concept of "reasons attributable to the employer." It's not strictly fault-based and can include business or managerial issues on the employer's side that lead to a work stoppage.

- "Reasons Attributable to the Employer" under LSA Art. 26 Defined: The Supreme Court's interpretation of this phrase in LSA Art. 26 as being wider than its Civil Code counterpart is highly significant. It implies that even without direct fault, an employer might be liable for leave allowance if the work stoppage stems from, for example, material shortages, facility malfunctions, or other operational decisions directly within the employer's managerial sphere. This interpretation has been influential beyond strike scenarios, for instance, in guiding the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare's approach to leave allowances during the COVID-19 pandemic.

- Partial Strikes and Non-Striker Rights:

- This case involved a "partial strike" (部分スト - bubun suto), where the non-striking employees (Mr. X et al.) were members of the same union (Union Z) that conducted the strike in a different location (Tokyo).

- The Court's finding was that even under the broader LSA Art. 26 standard, a strike resulting from the "subjective judgment and responsibility" of the union is not a "reason attributable to the employer" for the purpose of granting leave allowance to these non-striking members of the same union. The cause of their inability to work was rooted in their own union's actions.

- The PDF commentary accompanying this case notes an important distinction often made in legal theory: "one-part strikes" (一部スト - ichibu suto), where non-strikers are not members of the striking union (e.g., they belong to a different union or are non-unionized). While this judgment denied leave allowance in a partial strike scenario, academic opinion strongly suggests that in a one-part strike, where non-striking employees are entirely independent of the striking union, a claim for leave allowance under LSA Art. 26 should be recognized if their work becomes impossible due to the strike. This specific judgment does not rule on such a scenario but provides a crucial piece of the puzzle.

- Employer's Responsibility in Labor Disputes: The Supreme Court was disinclined to attribute the cause of the strike to the employer based on the history of the labor dispute. It acknowledged the employer's attempts to propose solutions and placed the ultimate responsibility for the strike action on the union. This suggests that unless an employer's actions are clearly unreasonable or constitute unfair labor practices that provoke a strike, the strike itself will likely be viewed as an independent decision by the union.

Conclusion

The Northwest Airlines Supreme Court judgment of 1987 clarified that non-striking employees, whose inability to work is a consequence of a strike conducted by other members of their own union, are generally not entitled to claim full wages from their employer under the Civil Code, nor are they typically eligible for statutory leave allowance under Article 26 of the Labor Standards Act. This is because the strike, being an autonomous action of the union, is not considered a "reason attributable to the employer" under either the narrower Civil Code standard or the broader LSA standard in this specific context of a partial strike. The decision underscored the independence of union actions and provided a more nuanced understanding of employer responsibility in the complex dynamics of industrial relations.