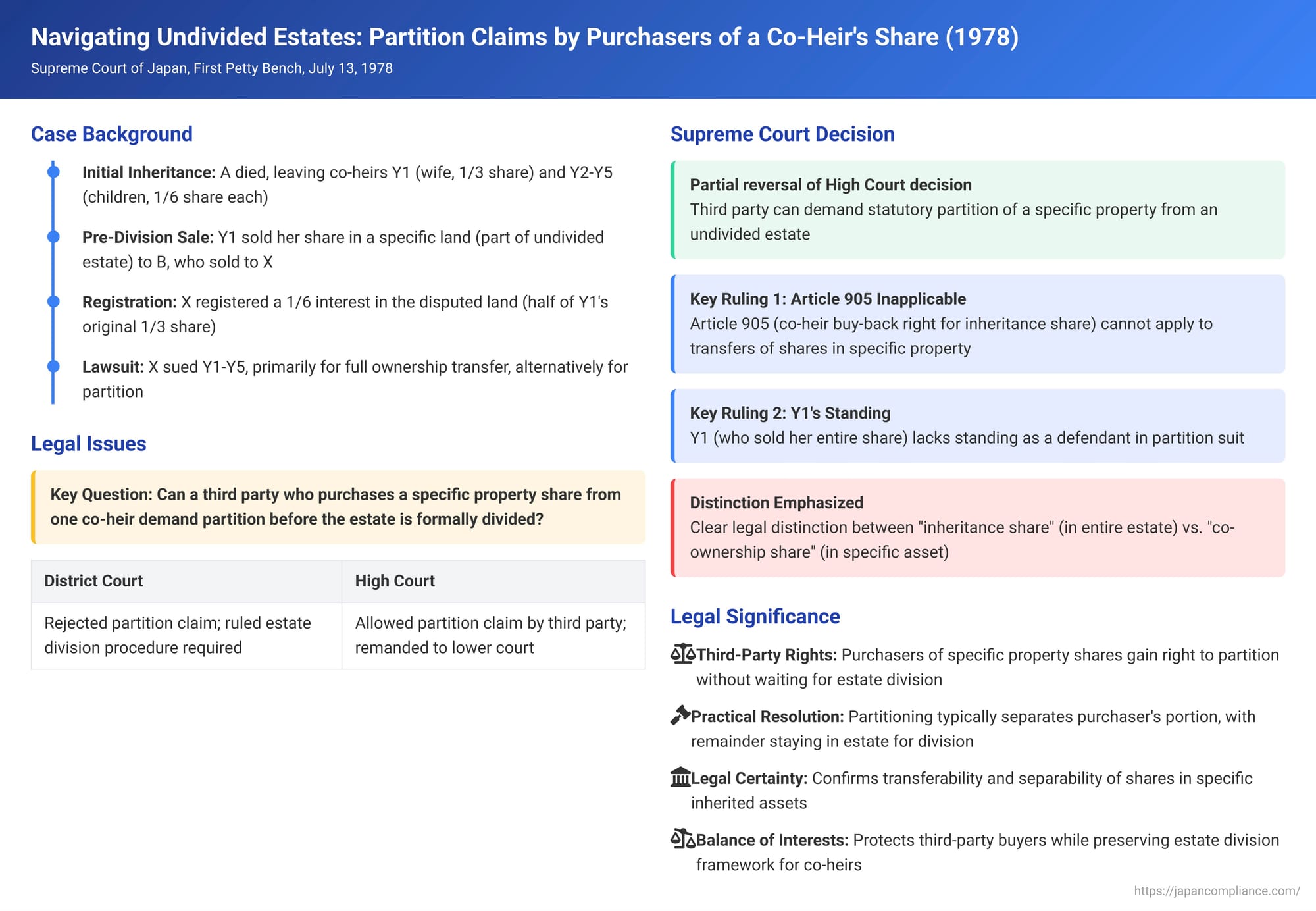

Navigating Undivided Estates: Partition Claims by Purchasers of a Co-Heir's Share in Specific Property

Date of Judgment: July 13, 1978

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench, Case No. Showa 52 (o) No. 1171 (Claim for Partition of Co-owned Property)

When an estate is inherited by multiple heirs, it enters a state of co-ownership until a formal estate division (遺産分割 - isan bunkatsu) is completed. Complications often arise if one co-heir, before this division, sells their interest in a specific piece of property within the undivided estate to a third party. Can this third-party purchaser demand a partition of that specific property? And what becomes of the selling co-heir's legal standing concerning that asset? The Supreme Court of Japan addressed these critical questions in its judgment on July 13, 1978, providing important clarifications on the rights of such purchasers and the nature of co-ownership in inherited assets.

Facts of the Case

The dispute centered around a parcel of land (the "Disputed Land") that was part of an undivided inherited estate.

- The Inheritance: A passed away, and the estate was jointly inherited by Y1 (A's wife) and Y2-Y5 (A's children). Under the Civil Code provisions applicable at the time (pre-1980 amendment), Y1's statutory inheritance share was 1/3, and the children Y2-Y5 each had a share of 1/6.

- The Transactions: Before the estate was formally divided, Y1, allegedly without the consent of Y2-Y5, purported to sell the Disputed Land (which was part of the inherited estate) to an intermediary, B. B subsequently sold this interest to X (the plaintiff).

- Property Registration: Following A's death, an inheritance-based registration was made for the Disputed Land, reflecting Y1's co-ownership share as 1/3 and Y2-Y5's shares as 1/6 each. Later, a further registration was made, transferring one-half of Y1's 1/3 share (amounting to a 1/6 interest in the entire Disputed Land) to X.

- X's Claims in Court: X initiated legal proceedings against all the co-heirs (Y1-Y5).

- X's primary claim was for the transfer registration of all co-ownership shares held by Y1-Y5 in the Disputed Land, based on the assertion that Y1 had effectively sold the entire property.

- Alternatively, X sought a statutory partition (共有物分割 - kyōyūbutsu bunkatsu) of the Disputed Land, asserting X's status as a co-owner by virtue of acquiring Y1's 1/6 interest.

- Lower Court Rulings:

- The court of first instance rejected X's primary claim, finding that Y1 did not have the authority to dispose of the shares belonging to Y2-Y5. It did, however, recognize the transfer of Y1's own share to X. Regarding X's alternative claim for statutory partition, the court dismissed it, stating that matters concerning the division of inherited property should be resolved through comprehensive estate division procedures, not a separate statutory partition of a single asset.

- The High Court, on appeal, upheld the dismissal of X's primary claim. However, it took a different view on the alternative claim. It ruled that X's request for statutory partition was permissible and remanded this part of the case back to the first instance court for further proceedings. It was this decision by the High Court that Y1-Y5 appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court's judgment addressed several key legal points:

1. Inapplicability of Article 905 of the Civil Code:

The appellants (Y1-Y5) had argued for the application of Article 905 of the Civil Code, which, under certain conditions, allows co-heirs to retrieve an inheritance share (相続分 - sōzokubun, meaning an heir's overall fractional interest in the entire estate) that has been assigned to a third party.

The Supreme Court affirmed the High Court's judgment on this point, definitively stating that Article 905 cannot be applied, even by analogy, to cases where a co-heir has transferred their co-ownership share (共有持分権 - kyōyū mochibunken) in a specific piece of real estate within the inherited property. The Court distinguished between the assignment of an heir's holistic "inheritance share" and the transfer of an interest in a particular asset.

2. Y1's Standing in the Partition Suit (Reviewed Ex Officio):

This was a central part of the Supreme Court's decision.

- The Court noted that the facts established by the High Court indicated that Y1 had sold her entire co-ownership interest (1/3, which was registered as a transfer of 1/6 of the whole to X) in the Disputed Land to B, who then sold it to X. The judgment text is specific that the sale concerned Y1's share in the "Disputed Land" (本件係争地), which was a subset of the overall inherited properties.

- Since Y1 had effectively divested herself of her entire co-ownership interest in the Disputed Land, she no longer held any such interest in that specific property.

- Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that Y1 lacked legal standing (当事者適格 - tōjisha tekikaku) as a party (specifically, as a defendant) in X's lawsuit seeking statutory partition of the Disputed Land. A person who is no longer a co-owner of a property cannot be a proper defendant in a suit to partition that property.

- Therefore, the first instance court's decision to dismiss X's partition claim with respect to Y1 was, in effect, correct, albeit for the reason of Y1's lack of standing rather than the procedural ground initially cited by the first instance court (i.e., that it should be an estate division).

- The Supreme Court also clarified that X had not acquired any share in other inherited lands besides the Disputed Land. Thus, X lacked standing to demand partition of those other lands from Y1-Y5.

Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court partially overturned the High Court's judgment. It quashed the part of the High Court's decision that had reversed the first instance court's dismissal of the partition claim concerning the Disputed Land against Y1 and concerning other lands against all of Y1-Y5. The Supreme Court effectively reinstated the dismissal of X's partition claim against Y1 for the Disputed Land (due to her lack of standing) and against all Y1-Y5 for any lands other than the Disputed Land (due to X having no share in them).

3. Permissibility of Statutory Partition by a Transferee (Underlying Premise):

While not the direct point of contention resolved by this particular appeal, the Supreme Court's judgment implicitly proceeded on a premise established in earlier case law, notably a Supreme Court decision from November 7, 1975 (Showa 50). This premise is that a third party who has validly acquired a co-ownership share in a specific property forming part of an undivided inherited estate can initiate a statutory partition lawsuit (under Article 258 of the Civil Code) for that specific property. Such a transferee is not necessarily forced to await or participate in the often more complex and comprehensive estate division proceedings covering the entire estate.

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1978 Supreme Court decision, along with the preceding and subsequent case law it forms a part of, carries significant implications:

- Distinction Between "Inheritance Share" and Asset-Specific Share: The case strongly reinforces the legal distinction between an heir's overall "inheritance share" in the entire estate and their co-ownership interest in a particular piece of inherited property. This distinction is crucial for determining applicable legal rules, such as the non-applicability of Article 905's buy-back provisions to transfers of shares in specific assets.

- Standing in Partition Suits: A party must hold a current co-ownership interest in the property to have standing in a statutory partition suit concerning that property. A co-heir who has sold their entire share in a specific asset is no longer a proper party to a partition suit for that asset.

- Rights of Third-Party Transferees: The line of Supreme Court decisions, including this one, affirms that third parties who purchase a co-ownership share in a specific inherited asset are entitled to seek a resolution of that co-ownership through a statutory partition. This allows them to extricate their interest from the complexities of the ongoing co-ownership and the internal dynamics of the original heirs' estate division.

- Mechanism of Partition Involving Inherited Shares: When such a partition occurs, the court's aim is typically to divide the specific property into a portion allocated to the third-party transferee (based on their acquired share) and a portion allocated to the remaining co-heirs (collectively). The portion allocated to the remaining co-heirs then continues to be subject to the internal estate division process among themselves.

The Broader Context: Balancing Interests

The Supreme Court's stance in these cases reflects an attempt to balance competing interests:

- Protecting Third Parties: It provides a mechanism for third parties who acquire shares in specific inherited properties to achieve clarity and separateness for their interest, upholding the principle that partition is a fundamental attribute of co-ownership.

- Preserving the Estate Division Framework: By allowing the third party to partition out only their specific interest in a particular asset, the remainder of that asset (if co-owned by multiple original heirs) and the rest of the undivided estate can still be managed and distributed through the comprehensive estate division process designed for co-heirs.

However, this approach has not been without criticism. Some commentators argue that a third party who knowingly acquires an interest in an undivided inherited property should perhaps be limited to remedies within the broader estate division process. There are also ongoing discussions about how best to protect third parties who transact with a single heir under the mistaken belief that the heir has sole authority or that the property is not part of an undivided estate. Later legislative changes and case law have continued to refine these areas, including methods for achieving partition, such as comprehensive monetary compensation.

Conclusion

The 1978 Supreme Court judgment is a key piece in the jurisprudential puzzle of how Japanese law handles transactions involving specific assets within an undivided estate. It clarifies the distinct nature of an asset-specific co-ownership share versus an overall inheritance share, defines the limits of co-heir buy-back rights, and underscores the importance of legal standing in partition suits. Most importantly, it confirms a pathway for third-party purchasers of such shares to seek a statutory partition, enabling them to manage their acquired interest even before the full estate division among the original heirs is complete. This contributes to a degree of legal certainty for third parties while attempting to respect the integrity of the internal estate division process among co-heirs.