Navigating the Nuances of Medical Liability in Japan: The "Expectation Right" and a Landmark Case

Date of Judgment: February 25, 2011, Supreme Court of Japan (Second Petty Bench)

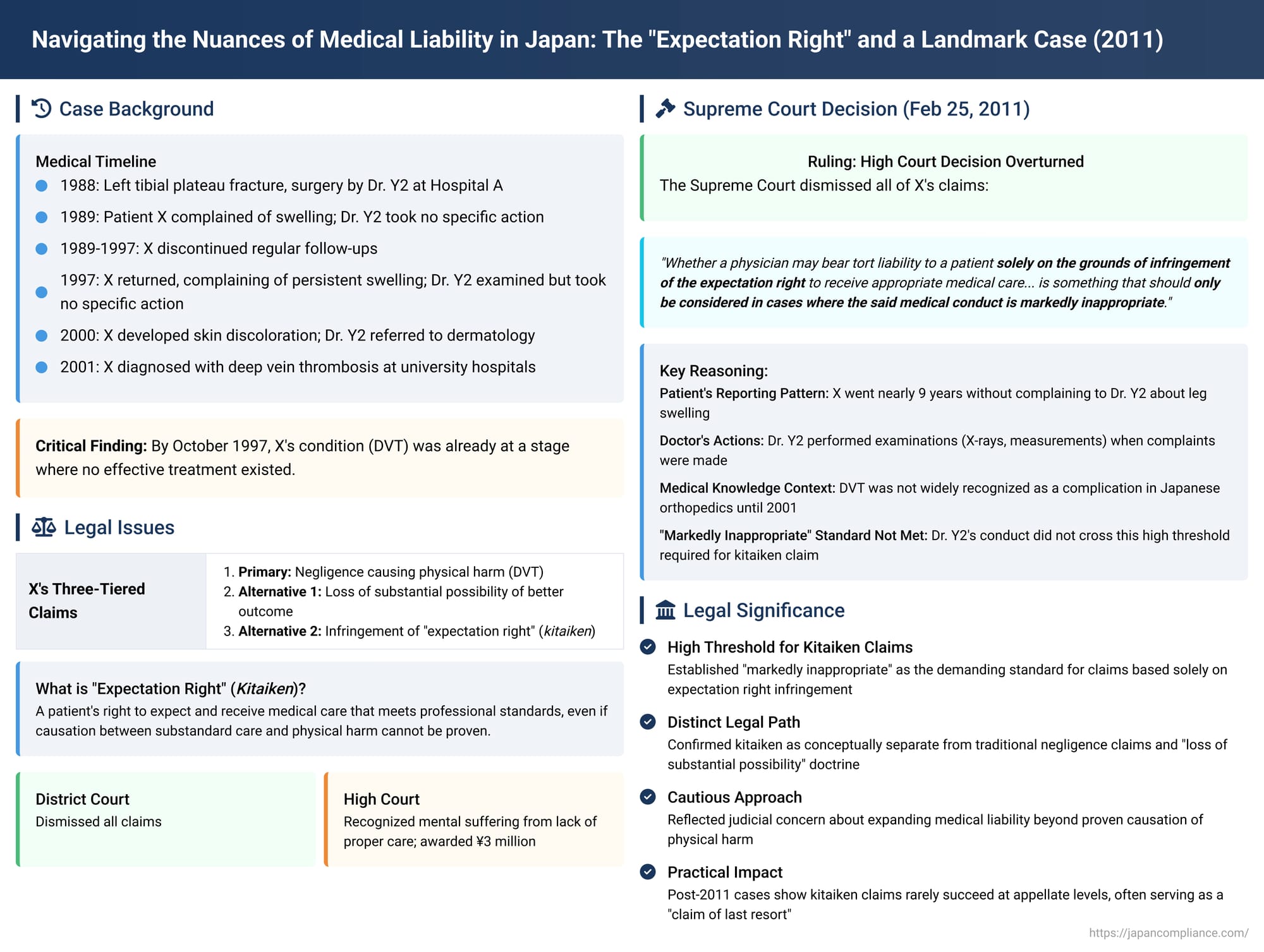

The realm of medical malpractice litigation often grapples with the intricate challenge of proving a direct causal link between a medical professional's actions (or omissions) and a patient's adverse outcome. In Japan, this challenge has led to the judicial exploration of unique legal concepts, one of the most notable being the "expectation right" (kitaiken, 期待権). This refers to a patient's right to expect and receive medical care that aligns with prevailing professional standards. A pivotal Supreme Court decision issued on February 25, 2011, shed significant light on the contours of this concept, particularly in situations where definitive medical negligence causing physical harm is difficult to establish. This article delves into the facts, legal arguments, and the ultimate judgment in this case, examining its implications for understanding medical liability in Japan.

The Factual Matrix: A Patient's Prolonged Journey

The case revolved around the medical treatment received by Mr. X, following a serious leg injury. His journey spanned over a decade, marked by persistent symptoms, multiple consultations, and an eventual diagnosis that came years after the initial problem began.

Initial Injury and Surgery (1988)

In October 1988 (Showa 63), Mr. X suffered a left tibial plateau fracture. He was admitted to A Hospital, an institution established by Y1, and underwent osteosynthesis (surgical fixation of bones) and a bone graft. The surgery was performed by Dr. Y2, an orthopedic surgeon at A Hospital.

Post-Operative Period and Early Complaints (1989)

Mr. X was discharged from A Hospital in January 1989 (Heisei 1). During his post-operative hospitalization and subsequent outpatient visits for rehabilitation—leading up to a second hospitalization in August 1989 for the removal of surgical bolts—Mr. X complained to Dr. Y2 about swelling in his left leg. However, Dr. Y2 did not conduct specific examinations or initiate treatment for this swelling at that time.

A Long Hiatus and Intermittent Visits (1989 - 1997)

After the bolts were removed in August 1989, Mr. X, by his own judgment, discontinued regular follow-up visits to A Hospital for his leg. Over the subsequent years, he did visit A Hospital and was seen by Dr. Y2 on three occasions for unrelated issues: for rib pain in July 1992 (Heisei 4), for back pain in June 1995 (Heisei 7), and again for back pain in August 1996 (Heisei 8). Notably, during these three consultations, Mr. X did not report any issues concerning the swelling in his left leg to Dr. Y2.

Re-emergence of Symptoms and a Crucial Consultation (October 22, 1997)

On October 22, 1997 (Heisei 9), approximately nine years after the initial surgery, Mr. X returned to A Hospital and consulted Dr. Y2, specifically complaining that the swelling in his left leg had persisted since the surgery. Dr. Y2 conducted an X-ray examination and measured the circumference of both legs, finding the left leg to be about 3 cm larger than the right. However, Dr. Y2 observed that Mr. X had a good range of motion in his left knee (0 to 140 degrees), experienced no tenderness upon palpation, and had been able to continue his work as a carpenter. Based on these findings, Dr. Y2 concluded that there was no functional impairment or significant problem and, therefore, took no specific measures in response to Mr. X's complaint about the swelling.

A critical finding of fact by the courts, pertinent to later legal arguments, was that by this date—October 22, 1997—Mr. X's underlying condition (later diagnosed as deep vein thrombosis) was already at a stage where no appropriate treatment method existed, and any treatment, even if administered, would not have been expected to yield positive effects.

Further Incidents and Worsening Condition (1998 - 2000)

In August 1998 (Heisei 10), Mr. X visited A Hospital again, this time for pain in his right big toe resulting from an injury. During this visit, he did not raise the issue of his left leg swelling with Dr. Y2.

Around February 2000 (Heisei 12), Mr. X's left leg symptoms worsened. He developed an egg-sized red bruise slightly above his left ankle. Subsequently, numerous dark red bruises and skin discoloration appeared, extending from below his left knee to his ankle. Following these developments, Mr. X consulted Dr. Y2 at A Hospital. Upon observing these symptoms, Dr. Y2 advised Mr. X to seek a consultation with a dermatology department.

Seeking Clarity and Eventual Diagnosis (2001)

On January 4, 2001 (Heisei 13), Mr. X revisited Dr. Y2 at A Hospital, complaining that the swelling and skin discoloration in his left leg were not improving. Dr. Y2 noted that Mr. X had consulted a dermatologist and had been diagnosed with "congestion" (鬱血 - ukketsu) and was receiving medication. Dr. Y2 performed an X-ray but took no further specific action.

Frustrated with the lack of improvement, Mr. X sought opinions from other medical institutions. Between April and October 2001, he visited Tottori University Hospital, Kyushu University Hospital, and Kobe University Hospital. At each of these university hospitals, he was diagnosed with either left lower limb deep vein thrombosis (DVT) or post-thrombotic syndrome (referred to in the judgment as "the sequelae in question" or "the present sequelae"). This syndrome is a long-term complication of DVT.

Medical Understanding at the Time

The courts acknowledged an important aspect of the medical context: the high frequency of DVT as a complication following lower limb surgery only became generally recognized among orthopedic surgeons in Japan from Heisei 13 (2001) onwards. Dr. Y2, prior to Mr. X receiving the DVT diagnosis from the university hospitals in 2001, had not suspected DVT as the underlying cause of Mr. X's persistent left leg symptoms.

The Legal Battle: Allegations and Defenses

Armed with the DVT diagnosis, Mr. X initiated legal proceedings against Dr. Y2 and Y1 (the operator of A Hospital), seeking approximately 57 million yen in damages based on tort. His claims were structured in a tiered manner:

- Primary Claim (Negligence and Causation): Mr. X alleged that Dr. Y2 had a duty to perform necessary examinations for his leg swelling or to refer him to a specialist in vascular diseases. He claimed that Dr. Y2 negligently breached this duty, and as a direct result, Mr. X developed and suffered from the post-thrombotic syndrome.

- Alternative Claim 1 (Loss of a Substantial Possibility): If the court found that a direct causal link between Dr. Y2's alleged breach of duty and the development of the post-thrombotic syndrome could not be proven, Mr. X argued, alternatively, that Dr. Y2's omissions had infringed upon his "substantial possibility" (相当程度の可能性 - soutou teido no kanousei) of avoiding the sequelae or achieving a better outcome.

- Alternative Claim 2 (Infringement of the "Expectation Right"): As a further alternative, if both direct causation and the loss of a substantial possibility were not established, Mr. X contended that Dr. Y2 had failed to provide appropriate and sincere medical care consistent with the medical standards reasonably expected at the time. This failure, he argued, infringed his "expectation right" (kitaiken) to receive such care, thereby causing him harm (e.g., prolonged suffering, lack of information, mental distress).

The Lower Courts' Journey

- District Court: The initial trial at the District Court concluded with a dismissal of all of Mr. X's claims. The court found no basis for liability against Dr. Y2 or Y1.

- High Court (Court of Appeal): Mr. X appealed to the High Court. The High Court partially reversed the District Court's decision. It did not find for Mr. X on his primary claim of negligence directly causing the post-thrombotic syndrome, nor on the loss of a substantial possibility of avoiding the physical sequelae. However, the High Court did find that Dr. Y2 had breached a duty of care. Specifically, it ruled that as of October 22, 1997 (when Mr. X complained of persistent swelling), Dr. Y2 had a duty to take further steps, such as referring Mr. X to a specialist. The High Court reasoned that Dr. Y2’s failure to do so meant that Mr. X was left for approximately three years without knowing the cause of his symptoms and was deprived of any treatment or guidance that might have been available at that point. This, the High Court concluded, caused Mr. X mental suffering. Consequently, the High Court ordered Dr. Y2 and Y1 to pay Mr. X 3 million yen in damages as compensation for this mental distress, effectively recognizing a form of harm stemming from the failure to provide adequate medical attention, even if that failure didn't provably alter the physical outcome.

Dr. Y2 and Y1 appealed this High Court decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Adjudication (February 25, 2011)

The Supreme Court's Second Petty Bench delivered its judgment on February 25, 2011. It overturned the High Court's ruling that had favored Mr. X and reinstated the District Court's original decision, ultimately dismissing Mr. X's claims in their entirety.

Core Reasoning of the Supreme Court

The Supreme Court meticulously reviewed the factual circumstances and the High Court’s legal reasoning, disagreeing with the latter’s conclusions.

- Patient's Reporting History: The Supreme Court placed significant emphasis on the timeline of Mr. X's complaints. It noted that while Mr. X did report left leg swelling during his initial post-operative period up until the bolt removal in August 1989, he then went nearly nine years without raising this specific complaint to Dr. Y2. His next documented complaint about the left leg swelling was on October 22, 1997. Even after this, his complaints about the leg were sporadic until the more alarming skin discoloration appeared in 2000.

- Dr. Y2's Actions: The Court acknowledged that Dr. Y2 did not simply ignore Mr. X's complaints when they were made. On October 22, 1997, Dr. Y2 performed an X-ray and measured the leg. When Mr. X presented with skin discoloration in 2000, Dr. Y2 recommended a dermatology consultation. Later, in January 2001, another X-ray was performed.

- Prevailing Medical Knowledge Regarding DVT: A crucial element in the Supreme Court's assessment was the state of general medical knowledge among orthopedic surgeons in Japan at the relevant times. The Court reiterated the finding that the high incidence of DVT as a complication of lower limb surgery was not widely recognized in the Japanese orthopedic community until 2001 or later. This meant that during most of the period when Mr. X was experiencing symptoms and consulting Dr. Y2 (prior to 2001), DVT was not an obvious or commonly suspected diagnosis for an orthopedic surgeon in Dr. Y2's position under similar circumstances.

- Assessment of Dr. Y2's Conduct – The "Markedly Inappropriate" Standard: Based on the above points—Mr. X's inconsistent reporting, Dr. Y2's responsive actions (albeit not leading to a DVT diagnosis), and the limited awareness of DVT prevalence at the time—the Supreme Court concluded that Dr. Y2's failure to suspect DVT or to refer Mr. X to a vascular specialist earlier could not be characterized as "markedly inappropriate" (著しく不適切な - ichijirushiku futekisetsu na). The judgment explicitly stated: "it is clear that Dr. Y2's aforementioned medical conduct cannot be said to have been markedly inappropriate."

- The "Expectation Right" (Kitaiken) Threshold: This conclusion was pivotal for the Supreme Court's handling of Mr. X's claim regarding the infringement of his "expectation right." The Court articulated its stance on this specific type of claim as follows:

"Whether a physician may bear tort liability to a patient solely on the grounds of infringement of the expectation right to receive appropriate medical care, in cases where the patient was unable to receive such care, is something that should only be considered in cases where the said medical conduct is markedly inappropriate." (Emphasis added).

Since the Court had already determined that Dr. Y2's conduct did not meet this high threshold of being "markedly inappropriate," it followed logically that there was no basis to consider liability for an infringement of the expectation right. The judgment stated: "The present case cannot be said to be such a case. Therefore, there is no room to examine the existence or non-existence of the aforementioned tort liability for [Dr. Y2 and Y1], and it should be said that [they] do not bear tort liability to [Mr. X]." - Regarding the Futility of Treatment by 1997: The Supreme Court also implicitly acknowledged the earlier finding that by October 22, 1997, no effective treatment was available for Mr. X's condition. This undercut the High Court's reasoning that Mr. X was deprived of "treatment or guidance that could have been provided." If no effective treatment could have been provided, the failure to refer for such treatment could not have caused the loss of a chance for a better physical outcome. The mental suffering component, while acknowledged by the High Court, was not deemed sufficient by the Supreme Court to establish liability under the stringent "markedly inappropriate" standard required for an expectation right claim.

No Liability Found: Consequently, the Supreme Court quashed the part of the High Court judgment that had found Y1 and Y2 liable and ordered them to pay damages. It upheld the original District Court decision, which was to dismiss Mr. X's claim.

Dissecting the "Expectation Right" (Kitaiken) in Japanese Medical Malpractice

The Supreme Court's 2011 judgment is a significant landmark in the evolving jurisprudence surrounding the "expectation right" in Japanese medical malpractice law.

Conceptual Basis of Kitaiken

The "expectation right" is not a right explicitly codified in Japanese statutes like the Civil Code. Instead, it is a concept that has been predominantly developed and debated within case law. It generally refers to a patient's inherent and legitimate expectation that the medical care they receive will adhere to the professional standards prevalent at the time of treatment. It embodies the idea that a patient entrusts their health and well-being to medical professionals and, in return, can reasonably expect competent, diligent, and sincere medical attention.

Distinction from Traditional Negligence, Causation, and "Loss of Substantial Possibility"

- Traditional Negligence: Standard medical malpractice claims require the plaintiff to prove three core elements: (i) a duty of care owed by the medical professional to the patient, (ii.ii) a breach of that duty (negligence), and (iii) harm or injury to the patient that was directly caused by that breach. Proving the causal link (iii) can be exceptionally difficult in complex medical scenarios where multiple factors might contribute to an outcome.

- "Loss of a Substantial Possibility": Recognizing the difficulties in proving direct causation, Japanese courts, including the Supreme Court in earlier key precedents (e.g., decisions on September 22, 2000, and November 11, 2003), have embraced the doctrine of "loss of a substantial possibility." This doctrine allows for compensation if a doctor's negligence, while not definitively proven to have caused the ultimate negative outcome (like death or severe permanent impairment), is shown to have deprived the patient of a "substantial possibility" or a significant chance of a better outcome. This doctrine somewhat eases the burden of proving strict causation for the ultimate harm.

- Kitaiken as a Distinct Concept: The "expectation right," particularly as framed in the arguments in Mr. X's case and discussed by the Supreme Court, is posited as a potential basis for damages even when direct causation of the physical harm (the sequelae) or the loss of a substantial possibility of avoiding that physical harm cannot be proven. The alleged harm in a pure kitaiken infringement claim is, in essence, the denial of the right to receive appropriate medical care itself. This denial can lead to various forms of suffering, such as prolonged uncertainty, anxiety, lack of necessary information or guidance, or the feeling of being let down by the medical system, irrespective of whether the physical outcome would have been different with better care.

The "Markedly Inappropriate" Standard: A High Bar

The 2011 Supreme Court judgment is particularly noteworthy for its explicit articulation of the standard required to potentially sustain a claim based solely on the infringement of the expectation right. The Court did not completely reject the theoretical possibility of such claims. However, it established a very demanding threshold: such claims would only merit consideration if the medical conduct in question was "markedly inappropriate" (ichijirushiku futekisetsu na).

This phrase implies a standard of conduct that is significantly worse than simple negligence or a mere error in judgment. "Markedly inappropriate" suggests medical care that falls so far below the accepted norms and standards of the medical profession at the time that it could be considered grossly deficient, exceptionally poor, or perhaps even indefensible. It signals a qualitative difference, not just a quantitative one, from an ordinary breach of duty.

Historical Context and Judicial Deliberation

The notion of compensating patients for harms related to the quality of care, distinct from provable physical injury caused by that care, has appeared in Japanese jurisprudence before this 2011 ruling.

For example, a Fukuoka District Court decision in 1977 (Showa 52.3.29) is often cited as an early instance where the term "expectation right" was used. In that case, a patient died, but causation between alleged medical negligence and the death could not be definitively established because the bereaved family had refused an autopsy. The court, however, acknowledged that the patient had an expectation of receiving adequate medical observation and management under the medical contract. It found that this expectation was breached and awarded consolation money (a form of non-pecuniary damages) for this breach, even without proof of causation for the death.

Over the years, various lower courts have grappled with similar situations, sometimes using phrases like the patient being "unjustly deprived of the opportunity to receive appropriate treatment" rather than explicitly naming an "expectation right."

Within the Supreme Court itself, individual opinions in other cases preceding the 2011 judgment (for instance, in a decision from December 8, 2005, concerning medical care for a detained individual) also reflected judicial consideration of these issues. Some justices argued in favor of recognizing the infringement of the "benefit of receiving timely and appropriate medical examination, treatment, etc." as a distinct legal harm. Conversely, other justices expressed concerns that an overly broad interpretation of an abstract "expectation right" could lead to an excessive expansion of medical liability. These cautious voices suggested that if such a right were to be recognized as an independent basis for damages, it should be strictly confined to exceptional circumstances involving medical conduct that was, for example, "unworthy of the name of medical practice" or "markedly inappropriate and insufficient."

The 2011 Ruling's Cautious Approach

The Supreme Court's February 25, 2011, judgment in Mr. X's case clearly reflects this cautious and restrictive approach. By establishing the "markedly inappropriate" conduct standard, the Court signaled that while the conceptual door for claims based purely on an infringed expectation right is not entirely slammed shut, it is, at best, only slightly ajar. This standard reserves such claims for truly egregious deviations from acceptable medical practice. The ruling carefully balances the patient's legitimate desire for diligent and respectful care against the need to protect medical professionals from liability for diagnostic uncertainties or outcomes that are less than perfect, provided their conduct does not descend to the level of being "markedly inappropriate."

The Aftermath and Practical Implications of the "Markedly Inappropriate" Test

The stringent "markedly inappropriate" test articulated by the Supreme Court has significant practical implications for medical malpractice litigation in Japan. It means that successfully pursuing a claim based solely on the infringement of the expectation right, especially when direct causation of physical harm or a loss of substantial possibility of a better outcome cannot be proven, is exceedingly difficult.

Post-2011 case law trends indicate that claims relying on this narrowed formulation of kitaiken have rarely succeeded, particularly at the appellate levels. There was one reported instance where a district court (Osaka District Court, July 25, 2011) found that a roughly 30-minute, human-error-caused delay in ordering emergency blood for a patient suffering a massive postpartum hemorrhage (amniotic fluid embolism with DIC) was "markedly inappropriate." This court initially awarded damages based on the infringement of the expectation right as per the Supreme Court's framework. However, on appeal, the High Court, while still finding for the plaintiff, based its larger damages award on the more established grounds of negligence leading to a loss of a substantial possibility of survival, rather than solely on the kitaiken infringement.

This pattern suggests that while the "expectation right" may be argued by plaintiffs, it often serves as a subsidiary or alternative plea—a legal argument of last resort when more traditional claims related to causation of physical harm or loss of substantial chance prove untenable. Legal practitioners are likely to be circumspect about making kitaiken the central argument of their case, given the exceptionally high bar set by the "markedly inappropriate" standard.

Conclusion: A Narrow Path for a Niche Claim

The Japanese Supreme Court's decision of February 25, 2011, in the case of Mr. X provides crucial clarification on the legal status of the "expectation right" (kitaiken) in medical malpractice. While the judgment acknowledges the fundamental principle that patients are entitled to expect appropriate medical care, it decisively restricts the scope for independent claims based solely on the breach of this expectation, especially when detached from proof of consequent physical harm or the loss of a substantial chance for a better physical outcome.

The imposition of the "markedly inappropriate" conduct standard means that such claims will only be viable in exceptional circumstances involving truly egregious failures in medical care. This ruling underscores the judiciary's ongoing effort to strike a delicate balance: upholding patient rights and ensuring accountability for substandard medical practice, while simultaneously recognizing the inherent complexities, uncertainties, and pressures of the medical profession, thereby preventing an undue expansion of liability. This judgment continues to be a significant reference point, shaping the strategies and outcomes in medical malpractice litigation in Japan.