Cross‑Border Trade Secret Disputes Involving Japan: Jurisdiction & Governing Law Guide

Learn how Japan’s 2024 UCPA changes affect jurisdiction and choice of law in cross‑border trade‑secret cases—and what US companies must do to stay protected.

TL;DR

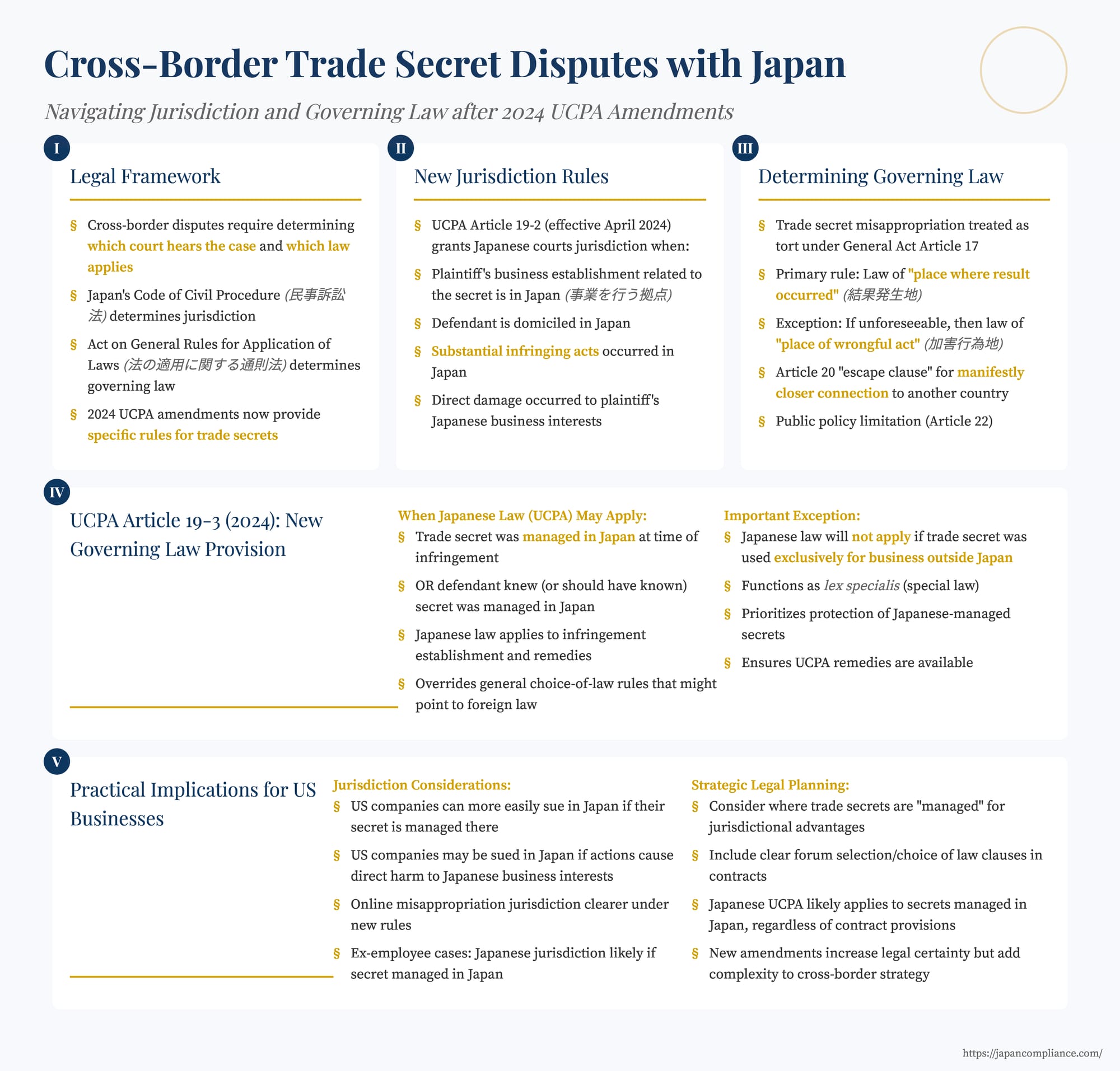

Japan’s 2024 amendments to the Unfair Competition Prevention Act give Japanese courts clearer jurisdiction and strengthen the likelihood that Japanese law governs when a trade secret is managed in Japan—even in cross‑border disputes. US businesses should map where secrets are “managed,” anticipate dual‑forum tactics, and align NDAs with these new rules.

Table of Contents

- Which Court Can Hear the Case? International Jurisdiction in Japan

- Which Law Applies? Choice of Law for Trade Secret Disputes

- Practical Takeaways for US Businesses

- Conclusion: Increased Clarity, Lingering Complexity

As US businesses increasingly engage in global R&D, supply chains, and partnerships, the risk of trade secret misappropriation often transcends national borders. When such disputes involve Japanese entities or actions connected to Japan, two critical preliminary questions arise: Which country's courts have jurisdiction to hear the case? And which country's substantive law will apply to resolve the dispute?

Japan has a framework for addressing these international private law issues, primarily through its Code of Civil Procedure (for jurisdiction) and the Act on General Rules for Application of Laws (for governing law). Furthermore, significant amendments to Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA), effective from April 1, 2024, have introduced specific provisions tailored to international jurisdiction and the applicable law in trade secret infringement cases, aiming to provide greater clarity and protection.

Which Court Can Hear the Case? International Jurisdiction in Japan

The authority of Japanese courts to adjudicate international disputes, including those involving trade secrets, is primarily determined by Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP - 民事訴訟法 Minji Sosho Ho). For trade secret misappropriation, which is considered a tort (不法行為 - fuho koi), a key provision is CCP Article 3-3, Item 8.

1. General Tort Jurisdiction (CCP Art. 3-3, Item 8):

This article grants Japanese courts jurisdiction over tort claims if the "place where the tort was committed" (不法行為があった地 - fuho koi ga atta chi) is within Japan. This phrase has consistently been interpreted by Japanese courts to encompass two main locations:

* The place where the wrongful act itself was committed (加害行為地 - kagai kouichi).

* The place where the direct result or damage from that act occurred (結果発生地 - kekka hasseichi).

2. The Challenge of "Result Occurrence Place" for Intangible Trade Secrets:

For physical injuries or property damage, pinpointing the place of the act or the result is often straightforward. However, for intangible assets like trade secrets, determining the "place where the result occurred" can be complex. Various legal theories have been discussed, including:

* The place where the trade secret was managed (管理地説 - kanrichi setsu).

* The place where the defendant committed an infringing act (e.g., illicit acquisition, use, or disclosure) (行為地説 - kouichi setsu).

* The marketplace where the plaintiff's competitive advantage was harmed (市場地説 - shijouchi setsu).

* The victim's principal place of business, where the economic impact of the misappropriation is primarily felt (被害者本拠地説 - higaisha honkyochi setsu).

Prior to recent UCPA amendments, Japanese courts often found jurisdiction if significant infringing acts (like disclosure or use of the trade secret) took place in Japan, but a universally accepted definition for "result occurrence place" in trade secret cases remained elusive.

3. New Specific Jurisdiction Rules under UCPA (Art. 19-2 - Effective April 1, 2024):

Recognizing the need for greater predictability in international trade secret disputes, the 2023 revision to the UCPA introduced Article 19-2, which establishes specific grounds for Japanese courts to exercise jurisdiction in civil cases concerning the infringement of trade secrets protected under Japanese law. A Japanese court will have jurisdiction if:

- (a) The plaintiff's business establishment (事業を行う拠点 - jigyo o okonau kyoten) related to the trade secret is located in Japan. This focuses on where the secret is actually used or managed for business by the plaintiff.

- (b) The defendant is domiciled in Japan.

- (c) Multiple defendants are involved, and one of them is domiciled in Japan, and the claims are closely related.

- (d) A substantial part of the infringing acts (excluding mere online accessibility) occurred in Japan. This could include acts of acquisition, use, or disclosure within Japan.

- (e) The place where the damage (limited to direct damage) occurred is in Japan, provided the infringement causes harm to the plaintiff's business interests in Japan that are based on the trade secret.

This new Article 19-2 provides more concrete anchors for jurisdiction in trade secret cases than relying solely on the general tort provision of the CCP. For US companies, this means a higher likelihood of being able to sue in Japan if their Japanese operations manage or utilize the trade secret that was misappropriated, or if significant infringing acts occurred within Japan. Conversely, US companies could be sued in Japan if they are domiciled there or if their actions cause direct harm to Japanese trade secret-related business interests within Japan.

Which Law Applies? Choice of Law for Trade Secret Disputes

Once a Japanese court has jurisdiction, it must determine which country's substantive law will govern the merits of the trade secret claim. This is primarily guided by Japan's Act on General Rules for Application of Laws (法の適用に関する通則法 - Ho no Tekiyo ni Kansuru Tsusoku Ho, hereafter "General Act").

1. Trade Secret Misappropriation as a Tort (General Act Art. 17):

As with jurisdiction, trade secret misappropriation is characterized as a tort for choice-of-law purposes. Article 17 of the General Act lays down the primary rule:

* The claim is governed by the law of the "place where the result of the wrongful act occurred" (結果発生地 - kekka hasseichi). This is the principle of lex loci delicti commissi.

* Exception: If the occurrence of the result in that place was "ordinarily unforeseeable" by the defendant, then the law of the "place where the wrongful act was committed" (加害行為地 - kagai kouichi) applies instead. This exception aims to protect defendants from the application of an entirely unexpected foreign law.

The debate surrounding the definition of "result occurrence place" for governing law mirrors the jurisdictional discussion, with similar theories proposed. The focus is generally on where the direct harmful impact of the misappropriation is primarily experienced by the trade secret holder.

2. Manifestly More Closely Connected Law (General Act Art. 20):

Even if Article 17 points to a specific law, Article 20 provides an escape clause. If it is "manifestly more closely connected" with another country, the law of that other country will apply. This could be relevant, for example, if both the plaintiff and defendant are US companies, and the dispute primarily concerns actions and impacts within the US, even if some minor element touched Japan. It's also invoked where a tort is closely intertwined with a pre-existing contractual relationship (e.g., an NDA governed by a specific law, where the trade secret misappropriation also constitutes a breach of that NDA).

3. New Specific Governing Law Provision under UCPA (Art. 19-3 - Effective April 1, 2024):

Parallel to the new jurisdictional rule, the 2023 UCPA revision also introduced Article 19-3, which specifically addresses the law applicable to the infringement of trade secrets protected under the UCPA. This provision states that, regarding the establishment of infringement of a trade secret managed in Japan and the remedies available (such as injunctions and damages under the UCPA), Japanese law (i.e., the UCPA) may be applied, even if the general rules of the General Act (e.g., Article 17) would point to a foreign law.

This provision applies if either:

- The trade secret was managed in Japan at the time of infringement, OR

- The defendant knew (or was grossly negligent in not knowing) that the trade secret was managed in Japan.

However, there's an important exception: Japanese law will not be applied under this special rule if the trade secret was used exclusively for business outside Japan.

Article 19-3 significantly strengthens the potential application of Japanese UCPA to protect trade secrets managed within Japan, even in cross-border scenarios. It acts as a form of lex specialis (special law) or a strong public policy directive prioritizing the protection of Japanese-managed trade secrets under Japanese standards, particularly concerning the availability of UCPA-specific remedies. This means that even if a foreign law might theoretically apply under the General Act, if that foreign law doesn't offer protection equivalent to the UCPA for a secret managed in Japan, Japanese law can step in.

4. Public Policy and Other Limitations (General Act Art. 22):

Foreign law, even if designated by the General Act, will not be applied if its application would be contrary to Japanese public order or good morals. Furthermore, Article 22 states that if the act in question is not considered wrongful under Japanese law (even if it's wrongful under the otherwise applicable foreign law), no claim for damages or other remedies available under that foreign law can be made, except for remedies that are also recognized under Japanese law. This reinforces the baseline protection of Japanese law.

Comparative Note: The traditional Japanese approach of lex loci delicti (often focusing on where the damage is suffered) can be contrasted with, for example, the EU's Rome II Regulation, which has more specific rules for unfair competition (distinguishing between acts affecting competitors directly, where the law of the country where competitive relations or consumer interests are affected applies, and broader market harm). The US approach often involves a more flexible "most significant relationship" test or governmental interest analysis. The new UCPA provisions bring Japan closer to providing more targeted rules for trade secrets in line with international trends.

Practical Takeaways for US Businesses

The interplay of these rules, especially with the recent UCPA amendments, has several practical implications:

- Suing in Japan / Being Sued in Japan:

- A US company whose trade secrets managed in Japan (e.g., by a Japanese subsidiary or in a Japanese R&D facility) are misappropriated by a foreign entity may find it easier to establish jurisdiction in Japanese courts under the new UCPA Art. 19-2.

- Conversely, a US company whose actions (even if primarily outside Japan) cause direct damage to Japanese business interests reliant on a trade secret managed in Japan could find itself subject to Japanese court jurisdiction.

- Applicable Law:

- If a trade secret is managed in Japan, there's a strong likelihood that Japanese UCPA will now apply to questions of infringement and remedies (Art. 19-3 UCPA), potentially overriding a foreign law that might otherwise be indicated by general choice-of-law rules, unless the secret was used exclusively abroad.

- For NDAs and other contracts, while choice of law clauses are generally respected for contractual claims, tort claims for trade secret misappropriation will be analyzed under the statutory choice-of-law rules. However, a pre-existing contract and its chosen law can be a factor under the "more closely connected" test (General Act Art. 20).

- Specific Scenarios:

- Misappropriation by Ex-Employees Moving Internationally: If an employee of a US company's Japanese subsidiary misappropriates trade secrets managed in Japan and takes them to a new employer (US or other foreign company), Japanese courts may have jurisdiction, and Japanese UCPA may apply to the infringement.

- Online Misappropriation: If trade secrets are stolen and published online, affecting a US company's business in Japan (where the secret was managed or business interests are harmed), establishing jurisdiction and applying Japanese law is now more clearly supported by the UCPA amendments. The "place of the act" might be where the server is, but the "place of result/damage" or where the secret is "managed" could bring it within Japan's purview.

- Contractual Strategy: While statutory rules largely govern jurisdiction and choice of law for torts, clear contractual provisions in NDAs, employment agreements, and partnership agreements are still vital:

- Jurisdiction/Forum Selection Clauses: While not always binding for tort claims, they can influence courts or be determinative for related contract claims.

- Choice of Law Clauses: Similarly, primarily for contract claims.

- Confidentiality Obligations: Clearly define what constitutes a trade secret and the scope of permissible use, which can be relevant regardless of which law applies.

Conclusion: Increased Clarity, Lingering Complexity

The 2023/2024 amendments to Japan's Unfair Competition Prevention Act have brought welcome clarity to the often-murky waters of international jurisdiction and governing law in cross-border trade secret disputes. The new Articles 19-2 and 19-3 provide more specific grounds for Japanese courts to hear cases and apply Japanese law, particularly when trade secrets managed in Japan are at stake.

However, complexities remain. Determining the "place of management," the "place of substantial infringing acts," or "direct damage" will still require careful factual analysis. For US businesses, these developments underscore the importance of robustly managing trade secrets within their Japanese operations and understanding the reach of Japanese law. When disputes arise, a nuanced understanding of both the general principles of private international law and these new UCPA-specific rules will be crucial for developing effective litigation and dispute resolution strategies. Consulting with legal counsel experienced in Japanese IP and cross-border litigation is indispensable.

- Licensing Trade Secrets and Data in Japan: Navigating the Risks to Licensee Rights

- Protecting Your IP in Japan: Strategies for Patents, Trademarks, and Copyright

- What Is Japanese Digital Business Law, and How Will Evolving Tech Reshape It?

- Outline of the Unfair Competition Prevention Act (METI)

- Code of Civil Procedure – English Translation (Ministry of Justice)