Navigating the Lines of Legitimacy: Picketing and Employer Rights in Japan – The X Taxi Case (Supreme Court, October 2, 1992)

Case Reference: Claim for Damages

Court: Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench

Judgment Date: October 2, 1992

Case Number: (O) No. 676 of 1989

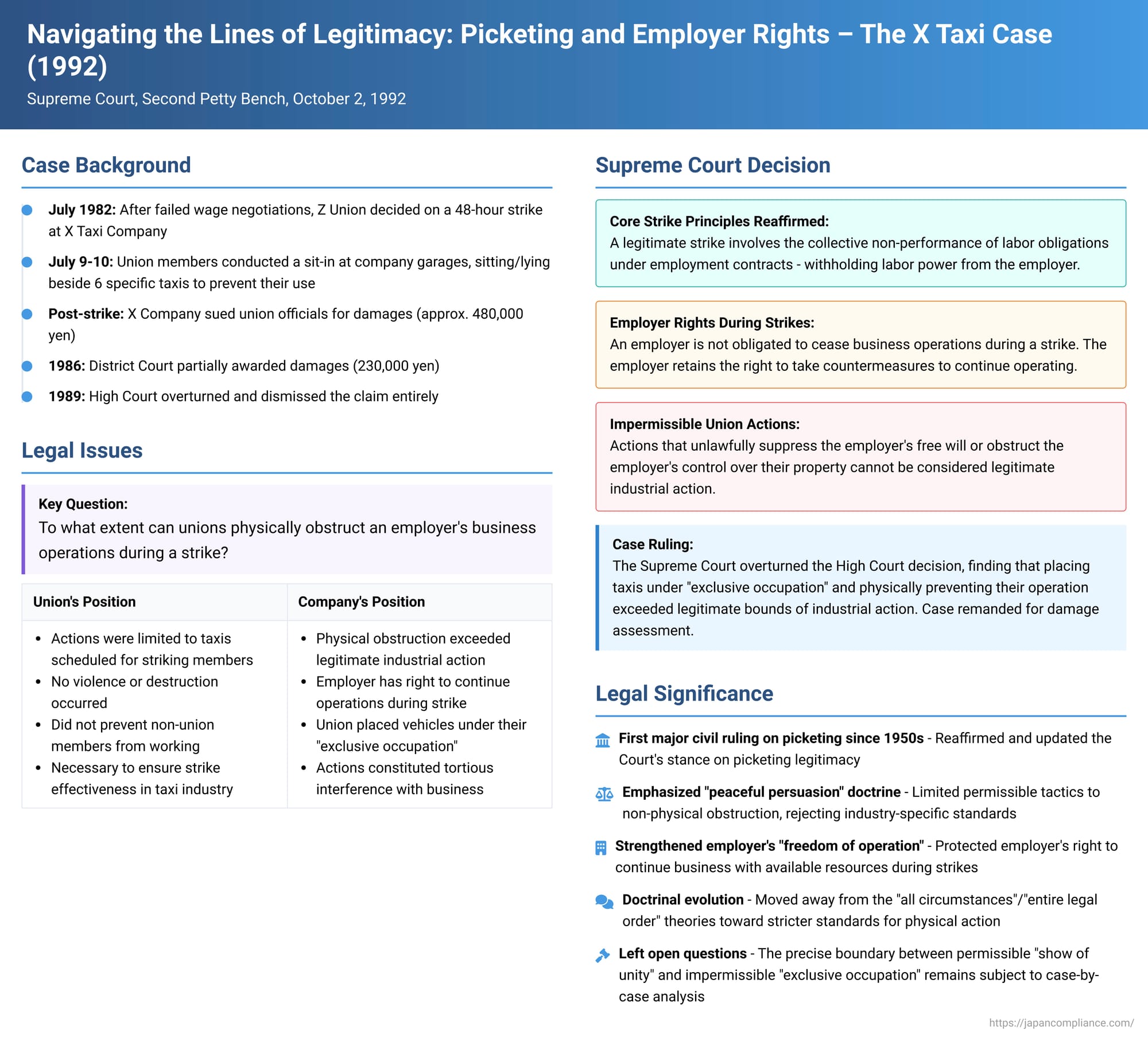

This article explores a key Japanese Supreme Court decision, commonly known as the X Taxi case (referring to the anonymized company name). This ruling, delivered on October 2, 1992, grapples with the complex legal boundaries of picketing during industrial disputes, particularly focusing on the extent to which unions can obstruct an employer's operations and property, and conversely, the scope of an employer's right to continue business during a strike. The case provides important clarifications on the concept of "legitimate industrial action" under Japanese labor law.

I. Background of the Dispute: From Failed Negotiations to a Garage Sit-in

The plaintiff, Company X (the appellant before the Supreme Court), was a taxi company operating in Kochi City. It employed approximately 115 individuals and maintained a fleet of 42 active taxis. The defendants, individuals Y1 through Y6 (the respondents), were members of Z Union, specifically its Local HQ (a unitary labor union for taxi workers in the prefecture formed through individual memberships) and/or officials of the M Branch, which consisted of 24 employees of Company X.

The dispute originated during the annual spring labor offensive (Shuntō) of 1982. The Local HQ of Z Union presented several demands to Company X, including an increase in basic wages, the payment of annual bonuses, and the conversion of temporary employees to permanent employee status. Collective bargaining sessions were held, but these negotiations ultimately failed to produce an agreement.

Facing this impasse, the Local HQ of Z Union decided to conduct a 48-hour strike, scheduled to commence from the start of the workday on July 9, 1982. Company X was formally notified of this impending strike on July 6.

In accordance with the Local HQ's decision, Y1 through Y6, along with other members of the M Branch and supporting members from the broader Local HQ, took action to prevent Company X from operating six specific taxis. These six vehicles (hereinafter "the Taxis in Question") were scheduled to be driven by members of the M Branch who were participating in the strike.

On July 9 and July 10, 1982, the union members, including the defendants, engaged in a sit-in at Company X's two garages where the Taxis in Question were stored. They positioned themselves by sitting or, in some instances, lying down beside these taxis. Despite requests from Company X management to vacate the premises, the union members refused to move. Consequently, Company X was unable to move the Taxis in Question out of the garages and operate them on either of these two days.

Following these events, Company X initiated legal proceedings against Y1 through Y6, seeking monetary damages of approximately 480,000 yen. The claim was based on tort, alleging that the union members' actions constituted an illegal obstruction of business.

II. Lower Court Rulings: A Divergence of Opinions

The case saw differing outcomes in the lower courts.

- Kochi District Court (May 6, 1986): The court of first instance partially found in favor of Company X, awarding damages of approximately 230,000 yen. The District Court determined that the union members' actions in preventing the taxis from being moved constituted an illegal obstruction of Company X's business operations through the use of physical force.

- Takamatsu High Court (February 27, 1989): The defendants appealed this decision. The Takamatsu High Court overturned the District Court's ruling and dismissed Company X's claim entirely. The High Court's reasoning centered on several observations:

- The Local HQ's actions specifically targeted only those taxis that were scheduled to be driven by striking union members.

- The union members did not engage in any destruction of the Taxis in Question. Furthermore, they did not seize control of essential items like engine keys or vehicle inspection certificates, which would have indicated an attempt to place the vehicles under the union's exclusive possession and control.

- There was no evidence that they had obstructed non-union members, who might have been scheduled to drive, from using the taxis in the normal course of their duties. Crucially, the union members did not resort to violence during their interactions with company management or other individuals.

- Considering these circumstances, the High Court concluded that the union members' actions did not deviate from the permissible scope of legitimate industrial action.

Company X subsequently appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Intervention: Overturning and Remanding

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of October 2, 1992, disagreed with the High Court's assessment and overturned its decision, remanding the case for further consideration of damages. The Supreme Court's reasoning was grounded in established principles of Japanese labor law concerning strikes and employer rights.

- Core Principles of Strike Legitimacy Reaffirmed:

The Court began by reiterating fundamental tenets:- While a strike inherently disrupts the normal operations of a business, its essential nature lies in the collective non-performance by workers of their labor supply obligations under their employment contracts. The method involves workers, acting in unity, withholding their labor power from the employer.

- Actions that unlawfully suppress the employer's free will or obstruct the employer's control over their property are not permissible and cannot be considered legitimate industrial action.

- Crucially, even during a strike, an employer is not obligated to cease business operations. The employer retains the right to take necessary countermeasures to continue operating. In stating these principles, the Supreme Court referenced its own landmark precedents, including the Asahi Shimbun Kokura Branch Case, the Haboro Coal Mine Case, and the Sanyo Electric Railway Case.

- Application to the Taxi Industry:

The Court emphasized that these principles apply fundamentally even to businesses like taxi services, where it might be perceived that the strike's effectiveness could be easily undermined by non-union members or replacement workers continuing operations. - Prohibition of Exclusive Occupation and Physical Obstruction:

The Supreme Court explicitly stated that it is impermissible for workers, during a strike, to go beyond the scope of persuasive activities and take actions that result in placing company vehicles, such as taxis, under their exclusive occupational control to prevent non-union members or others from operating them. Such acts of physically obstructing vehicle operation cannot be deemed legitimate industrial action. The Supreme Court specifically rejected the High Court's suggestion that workers in the taxi industry possess a right to physically prevent, to a certain extent, the continuation of operations by substitute personnel. - Evaluation of the Defendants' Actions in This Case:

Applying these principles to the facts, the Supreme Court found that Y1 through Y6, acting in concert and following the Z Union Local HQ's decisions, had effectively placed the Taxis in Question – which were under Company X's management and control – under the exclusive occupation of the Z Union Local HQ. By sitting or lying beside the taxis and refusing management's requests to vacate, they physically prevented Company X from moving and operating these vehicles. - Mitigating Factors Considered Insufficient to Confer Legitimacy:

The Supreme Court acknowledged several factors that the High Court had considered as mitigating circumstances. These included:However, even considering all these circumstances, the Supreme Court concluded that the defendants' actions in obstructing the operation of the vehicles went beyond the legitimate bounds of industrial action. The act of establishing exclusive occupation and physically preventing the use of company property was deemed illegal.- The purpose of the strike – to improve working conditions – was not in itself problematic.

- The union's tactic specifically targeted only those taxis that were due to be driven by its striking members, out of a larger fleet of 42.

- The union members did not seize engine keys or vehicle inspection documents, nor did they resort to violence or property destruction.

- Access to the garages by company management and other non-striking employees was apparently permitted.

- There were indications that the Z Union Local HQ had made efforts to avoid unnecessary confrontations, influenced perhaps by past practices in the region where dispute agreements sometimes allowed non-striking employees to continue working or by previous (though expired) agreements with Company X that outlined orderly conduct during disputes.

- Company X's management had primarily confined its response to requesting that the taxis be allowed to move, and had not attempted to forcibly remove them. Thus, the situation did not escalate to a point where the union members had to physically resist such an attempt with violence.

IV. Picketing in Japanese Labor Law: A Broader View

The X Taxi case offers a window into the broader legal treatment of picketing in Japan.

- Defining Picketing and Its Role:

"Picketing" in its original sense refers to the act of watching or keeping guard. In labor law, it's often categorized as a form of "positive industrial action" (sekkyokuteki sōgi kōi), meaning actions that go beyond the mere passive withdrawal of labor. There isn't a single, universally fixed definition of picketing in academic literature. Its scope can vary depending on the functions it's seen to pursue (e.g., strengthening union member solidarity and control, preventing the employer from accessing labor or product markets, publicizing the dispute), the targets of the picketing (e.g., union members, non-striking workers, the employer, suppliers, customers, or the employer's property), the specific methods used (e.g., monitoring, verbal appeals and persuasion, demonstrations of solidarity, or actual physical prevention of access or operations), and the location (e.g., inside or outside the employer's premises).

Despite this definitional breadth, there's a general consensus that picketing is typically conducted as an ancillary activity. Its main purpose is to ensure the effectiveness of a primary industrial action (like a strike) or to maintain and strengthen it.

Historically, in Japan, diverse forms of industrial action, including tactics like "production control" (seisan kanri, where workers take over the facility and continue production under their own management) and "workplace occupations" (shokuba senkyo), emerged in the immediate aftermath of World War II, following the enactment of the original Trade Union Act in December 1945. Picketing, alongside strikes, was also a frequently used tactic from this early period, and debates over its "legitimacy" – as per Articles 1(2) and 8 of the current Trade Union Act which grant immunities for proper industrial action – began relatively early. - Evolution of Supreme Court Doctrines on Picketing Legitimacy:

The Supreme Court's approach to picketing legitimacy has evolved through several key phases and conceptual frameworks:- The "Peaceful Persuasion" (Heiwateki Settoku) Theory: The Court first articulated a framework in civil cases. The Asahi Shimbun Kokura Branch Case (Supreme Court Grand Bench, October 22, 1952), cited in the X Taxi judgment, established that the essence of a strike lies in the non-performance of the duty to supply labor. Actions such as using violence or threats to obstruct the employer's performance of business were deemed to deviate from this essence and thus could not be considered legitimate industrial action.

Subsequently, in the Haboro Coal Mine Case (Supreme Court Grand Bench, May 28, 1958), a criminal case also cited in the X Taxi judgment, the Court stated that it is impermissible to unlawfully suppress the employer's free will or obstruct the employer's control over their property. These rulings helped crystallize the Supreme Court's "peaceful persuasion" doctrine, setting a standard that picketing should generally be limited to non-coercive methods. - The "All Circumstances" (Shōhan no Jijō) Theory: It's important to note that, particularly in criminal cases, the "peaceful persuasion" doctrine was not initially the sole determinant. The Haboro Coal Mine Case itself, while espousing peaceful persuasion as a general principle, also introduced the idea that the legitimacy of workers' use of force to halt an employer's operations during a labor dispute should be judged by considering "all circumstances." If such actions were found to exceed legitimate bounds based on this holistic assessment, they could constitute criminal offenses like forcible obstruction of business. This "all circumstances" approach provided a degree of flexibility in assessing the legitimacy of picketing.

- The "From the Standpoint of the Entire Legal Order" (Hōchitsujo Zentai no Kenchi) Theory: This combined framework, developed in the 1950s, was carried forward in subsequent Supreme Court criminal judgments. There were instances where this approach led to acquittals (e.g., Sapporo City Labor Federation Case, Supreme Court decision, June 23, 1970). During this period, some lower court civil judgments also adopted standards that appeared to permit "some degree of physical force" in picketing.

However, a shift occurred in the 1970s. In the JNR Kurume Station Case (Supreme Court Grand Bench, April 25, 1973), a criminal case involving railway workers, the Court stated that the legitimacy of a disputed act must be determined by "taking into account the concrete circumstances of the said act and other various circumstances, and judging whether or not it should be permissible from the standpoint of the entire legal order." Following this ruling, many commentators observed that the Supreme Court's willingness to meticulously consider the specific, nuanced circumstances of industrial actions significantly diminished. The Court appeared to adopt a stricter stance against the use of physical force, and acquittals in such cases became rare.

- The "Peaceful Persuasion" (Heiwateki Settoku) Theory: The Court first articulated a framework in civil cases. The Asahi Shimbun Kokura Branch Case (Supreme Court Grand Bench, October 22, 1952), cited in the X Taxi judgment, established that the essence of a strike lies in the non-performance of the duty to supply labor. Actions such as using violence or threats to obstruct the employer's performance of business were deemed to deviate from this essence and thus could not be considered legitimate industrial action.

V. Academic Discourse on Picketing

Academic views on picketing legitimacy have also been diverse and have evolved over time.

A major debate was sparked in 1954 by a Vice-Minister of Labor administrative circular which advocated for a strict application of what became known as the "absolute peaceful persuasion theory" – essentially arguing that picketing must be strictly limited to non-physical, persuasive activities.

However, even before this circular, a more moderate view, often termed "relative peaceful persuasion theory," held considerable sway. This theory suggested that the use of some physical force to prevent operations might be permissible depending on the target of the picketing (e.g., distinguishing between preventing strikebreakers and obstructing the employer themselves).

After the 1954 circular, a significant portion of academic opinion shifted towards a "physical prevention permissible theory" (jitsuryoku soshi yōnin setsu), which argued that, in principle, physical prevention could be a legitimate aspect of picketing under certain conditions.

Despite these vigorous debates, academic discussions specifically focused on picketing reportedly became less prominent from the 1960s onwards and were even described by some as having largely "concluded" or "ended" by around 1975, as other labor law issues came to the fore.

VI. The X Taxi (Mikuni Hire) Judgment in Context

It was against this backdrop of evolving case law and quieting academic debate that the X Taxi judgment emerged in the 1990s.

- Significance as a Modern Civil Ruling: It was hailed by some as the first "full-fledged Supreme Court civil judgment" on picketing since the landmark Asahi Shimbun Kokura Branch Case from decades earlier. The fact that it was an employer's claim for damages also made it somewhat unusual for its time.

- Factual Nuance of the Case: The X Taxi case involved what are known as "vehicle securing tactics" (sharyō kakuho senjutsu), where unions attempt to prevent the use of company vehicles during a strike. However, within this category, the degree of actual business obstruction or infringement upon property rights in this specific instance was considered by some commentators to be relatively minor compared to other potential scenarios.

- Divergence from the High Court: The High Court, while ostensibly relying on the Supreme Court's existing frameworks, had placed strong emphasis on the unique characteristics of the taxi industry. It suggested a standard where picketing or sit-ins would be deemed legitimate unless they completely "sealed off" the employer's ability to take countermeasures and were accompanied by violence or property destruction. The High Court viewed the defendants' actions in the X Taxi case as largely remaining within the scope of a "show of unity" (danketsu no jii).

- Supreme Court's Emphasis: The Supreme Court, in contrast, while citing the "peaceful persuasion" principle from its earlier cases, notably did not explicitly refer to the "all circumstances" or "from the standpoint of the entire legal order" doctrines that had featured in its criminal case law. Instead, it prominently cited and emphasized the employer's "freedom of operation" (sōgyō no jiyū), drawing from the Sanyo Electric Railway Case. It explicitly rejected the High Court's approach of tailoring the legitimacy standard based on the specific nature of the industry. The Supreme Court characterized the defendants' actions as "physical prevention" (jitsuryoku de soshi) of operations.

VII. Unanswered Questions and Future Implications

The X Taxi judgment left several questions open for interpretation and future development:

- Shift in Doctrinal Emphasis?: The Supreme Court's omission of the "all circumstances" and "entire legal order" considerations raised questions. Was this an intentional differentiation between the standards for civil and criminal cases regarding industrial action? Or was it a result of the specific factual context of "vehicle securing tactics"? Alternatively, was the Court signaling a move towards an even stricter standard of legitimacy for picketing in general, superseding the "entire legal order" approach? While some subsequent lower court civil judgments (particularly in damages claims) have cited the X Taxi ruling in contexts beyond vehicle securing tactics, there is no definitive consensus in academic evaluations regarding the precise scope and broader implications of this decision.

- Defining "Peaceful Persuasion" and "Exclusive Occupation": A critical point of divergence was the factual evaluation: the High Court saw a "show of unity," while the Supreme Court saw "physical prevention" leading to "exclusive occupation." Contemporary leading academic theories, even those that align with the "absolute peaceful persuasion" lineage, often argue that "persuasion accompanied by a show of unity" – which goes beyond mere verbal appeals – should still be considered within the bounds of "peaceful persuasion." In the X Taxi case, the Supreme Court's assessment that the defendants had placed the taxis under their "exclusive occupation" (haitateki senyū ka) appears to have been the decisive factor in deeming their actions illegal.

However, the precise substantive meaning of "peaceful persuasion" within the overall body of Japanese case law, and the criteria for determining when a "show of unity" crosses the line into impermissible "exclusive occupation" or "physical prevention," remain somewhat elusive and are subjects of ongoing debate and development.

The X Taxi ruling stands as a significant marker in Japanese labor law, reinforcing the employer's right to continue operations during a strike and setting limits on picketing activities that involve the physical obstruction of company property and operations. It underscores that actions deemed to place company assets under the union's "exclusive occupation" are likely to be found illegitimate, regardless of other potentially mitigating circumstances like the absence of violence or the limited scope of the targeted assets.