Navigating the Future of Compensation: Japan's Supreme Court on Periodic Payments for Lost Earnings

Date of Judgment: July 9, 2020

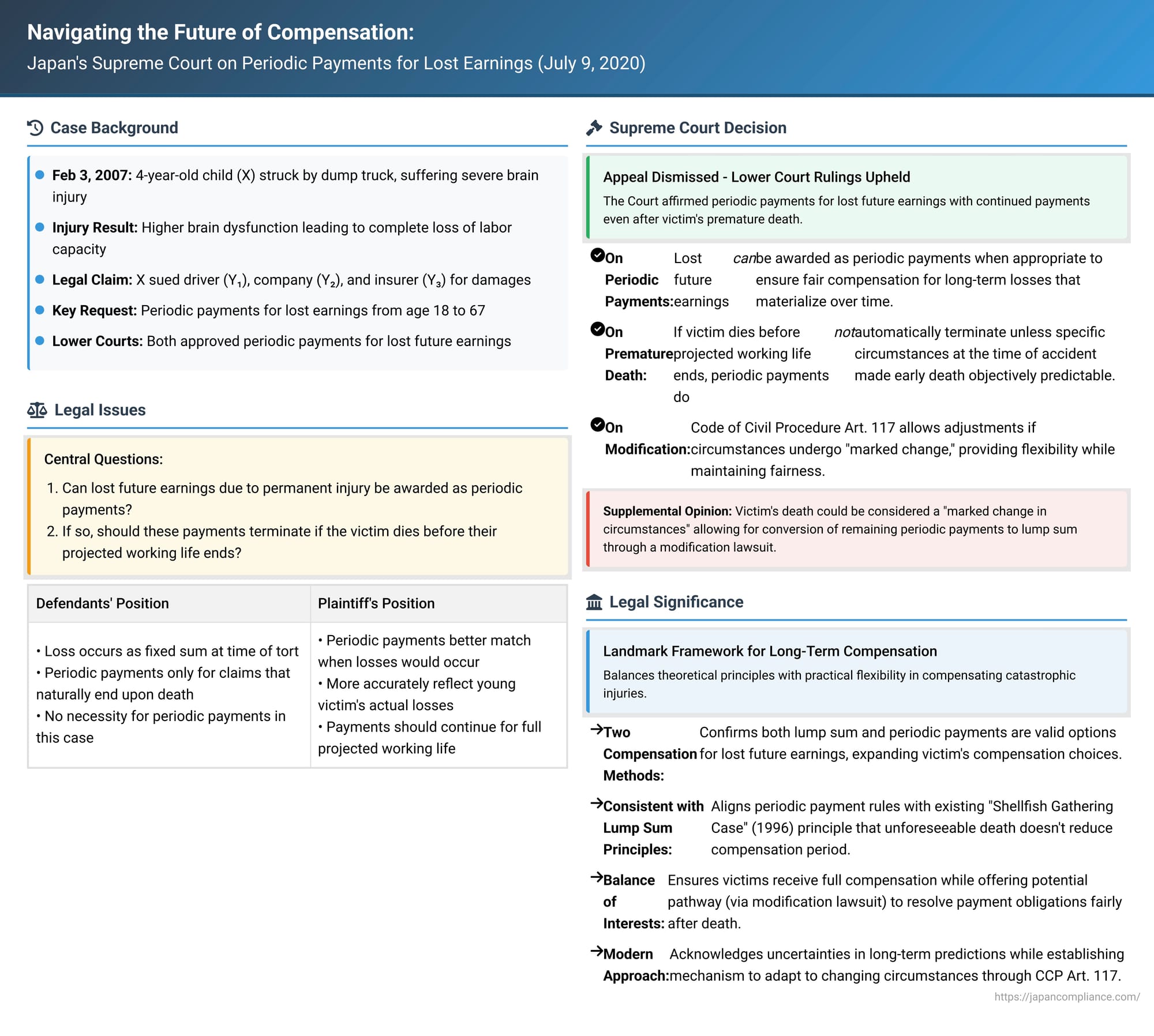

In a significant decision impacting how victims of catastrophic accidents are compensated for long-term losses, the Supreme Court of Japan clarified its stance on awarding lost future earnings through periodic payments. This ruling addresses crucial questions: Can future income loss due to permanent injury be paid out over time, rather than as a single lump sum? And, critically, what happens to these payments if the victim passes away before the anticipated end of their working life?

This decision, arising from a tragic traffic accident, delves deep into the principles of tort law, the nature of damages, and the mechanisms for ensuring fair and adequate compensation in the face of life-altering injuries.

The Case: A Life Irrevocably Changed

The case, Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, 2018 (Ju) No. 1856, concerned a young victim, X, who was only four years old at the time of the accident on February 3, 2007. X was crossing a road when struck by a large dump truck driven by Y₁ and owned by Company Y₂.

The consequences for X were devastating. The accident caused severe injuries, including a brain contusion and diffuse axonal injury, leading to permanent higher brain dysfunction. This condition resulted in a complete loss of X's labor capacity, categorized under Japan's Automobile Liability Security Act Enforcement Ordinance as a very severe disability.

Seeking redress, X (through representatives) filed a lawsuit against Y₁ (the driver) based on general tort principles (Civil Code Art. 709), and against Company Y₂ (the vehicle owner) under the Automobile Liability Security Act Art. 3. A claim was also made against Insurance Company Y₃, which had an automobile liability insurance contract with Company Y₂, for payment equivalent to the damages awarded, conditional upon a final judgment against Y₁ or Company Y₂.

A key aspect of X's claim was the request for compensation for lost future earnings. Specifically, X sought periodic payments to cover the income that would have been earned from the month after turning 18 (the presumed start of the working period) until the month of turning 67 (the presumed end of the working period).

Lower Courts Endorse Periodic Payments

Both the court of first instance and the subsequent appellate court sided with X, affirming the appropriateness of awarding lost future earnings through periodic payments. Dissatisfied with this outcome, the defendants (Y₁, Company Y₂, and Insurance Company Y₃) appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that lost future earnings arise as a fixed sum at the time of the unlawful act and that periodic payments should only be permissible for types of claims that naturally terminate upon the victim's death. They further contended that, in this specific case, the conditions of necessity and appropriateness for ordering periodic payments were not met.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Pronouncements

On July 9, 2020, the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, dismissing the appeal and upholding the lower courts' decisions. The Court's reasoning provided crucial clarifications on the use of periodic payments for lost future earnings.

1. Lost Future Earnings: A Candidate for Periodic Payments

The Court first addressed whether lost future earnings due to permanent injuries can be awarded as periodic payments.

It began by reaffirming a standard principle: a damage compensation obligation arising from a single unlawful act is considered one indivisible obligation, and the damage itself is deemed to occur at the moment of the unlawful act. Consequently, it's permissible to calculate the total sum of lost future earnings due to diminished or lost labor capacity and order this as a lump-sum payment.

However, the Court highlighted a critical characteristic of such damages: they materialize sequentially over a considerable period after the unlawful act. Calculating this future loss inevitably involves predictions and assumptions about uncertain future elements, such as the ongoing severity of the disability, future wage levels, and other evolving economic factors. This predictive nature means that significant discrepancies can emerge between the initially calculated lump-sum amount and the actual losses that eventually unfold.

The Court noted that Japan's Civil Code (Art. 722(1) concerning torts, and Art. 417 concerning monetary compensation) does not mandate that damages must only be paid as a lump sum. Furthermore, the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP) Art. 117 explicitly provides for a lawsuit to modify a final judgment that orders periodic payments if the circumstances forming the basis of the original calculation undergo a "marked change." The Court interpreted the purpose of CCP Art. 117 as acknowledging that for damages which, although existing in principle at the time of the judgment, will only become concrete with the passage of time, periodic payments can be a suitable method. The modification mechanism then allows for adjustments to ensure the compensation aligns with the reality of the loss, promoting fairness.

Drawing on the fundamental aims of the tort compensation system – to monetarily assess the victim's actual damages, have the tortfeasor compensate for these, thereby restoring the victim (as much as possible) to their pre-tort state, and to achieve a fair distribution of the burden of loss – the Court found that periodic payments can be an appropriate method. Specifically for lost future earnings due to permanent injury, ordering payments to correspond with the periods in which the income would have been earned, coupled with the possibility of adjustment under CCP Art. 117 if significant discrepancies arise, can be deemed "appropriate."

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that when a victim requests periodic payments for lost future earnings due to accident-induced permanent injuries, such earnings can be the subject of periodic payments if deemed appropriate in light of the purpose and principles of the tort compensation system.

2. The Specter of Premature Death: Does It Curtail Payments?

The second major issue was whether, if periodic payments are ordered, the victim's subsequent death (before the end of the originally assessed working life) automatically shortens the payment period to the date of death.

The Court drew a parallel to how lost future earnings are calculated for lump-sum payments. In that context, established case law (e.g., Supreme Court, April 25, 1996) dictates that even if a victim dies after the accident but before the conclusion of their projected working life, this subsequent death is not factored in to reduce the working period, unless at the time of the accident, specific reasons existed that made the victim's imminent death objectively predictable.

The Court reasoned that periodic payments for lost future earnings stem from the same single right to compensation that arises at the time of the accident and target the same damages as a lump-sum award. It would, the Court stated, contravene the principle of fairness if a liable party were to be relieved of all or part of their compensation obligation simply because the victim later died from causes unrelated to, and unforeseeable at the time of, the accident. This would leave the victim or their heirs without full recompense for the damages sustained. This principle holds true regardless of whether compensation is structured as a lump sum or as periodic payments.

Consequently, the Supreme Court held that when ordering periodic payments for lost future earnings due to permanent injury, the subsequent death of the victim before the end of the assumed working period does not mean the payment period automatically ends at the victim's death, unless specific circumstances were present at the time of the accident that made the victim’s early death objectively predictable.

Application to X's Case

Applying these principles, the Court found that X, who was a young child at the time of the accident and suffered a complete loss of labor capacity due to higher brain dysfunction, was facing a situation where lost earnings would materialize over a very long future period. Considering these and other circumstances, making periodic payments the method of compensation was deemed consistent with the purpose and ideals of the tort compensation system.

Furthermore, the Court found no evidence of any "special circumstances" existing at the time of the accident that would have made X's premature death objectively predictable. Thus, the lower courts were correct in not stipulating that the periodic payments would terminate upon X's potential death before reaching the age of 67.

The Supplemental Opinion: A Practical Path for Payers?

One of the Justices offered a supplemental opinion, agreeing with the majority but addressing a potential point of concern: the "awkwardness" some might feel about periodic payments continuing to a victim's heirs long after the victim's death.

The supplemental opinion suggested that the victim's death, which effectively ends any future variability in the extent of their disability or other related factors for the remaining period, could be construed as a "marked change in circumstances" relevant to the calculation of damages. If so, the party liable for payments (the defendant) could potentially file a lawsuit under CCP Art. 117 (or by analogy to it) after the victim's death. This lawsuit would seek to modify the original judgment, converting the remaining periodic payments for the rest of the originally determined working period into a single lump-sum payment, calculated at its present value as of the time the modification lawsuit is filed. This, the Justice suggested, could be a viable way to resolve the obligation for ongoing periodic payments.

The supplemental opinion also touched upon the criteria for determining the "appropriateness" of ordering periodic payments in the first place, given the lack of explicit substantive legal provisions. It suggested that this determination should be guided by the overarching purpose and principles of the tort compensation system, the rationale behind periodic payments, and their connection to the procedural remedy of a modification lawsuit under CCP Art. 117. It cautioned against giving undue weight to factors such as the administrative burden of managing periodic payments or debates around interim interest deductions (which are often seen as a technical means to achieve present value rather than a fundamental aspect of the damage itself).

Unpacking the Judgment: Deeper Currents and Interpretations

The Supreme Court's decision, while providing clear directives, also opens avenues for deeper analysis regarding the conceptual underpinnings of how such damages are understood. The interplay between the idea of damage being fixed at the time of the tort and the flexibility offered by periodic payments invites careful consideration.

Two broad ways of conceptualizing the damage and the role of periodic payments emerge from legal scholarship and are implicitly touched upon by the judgment and its supplemental opinion:

Lens 1: The "Single, Fixed Damage" Perspective

This view, which seems to align with the majority opinion's core reasoning, emphasizes that the entire damage – including all future lost earnings – arises as a single, ascertainable (though perhaps difficult to precisely calculate upfront) quantum at the moment of the unlawful act. The loss of labor capacity is the fundamental injury, and lost future earnings are the measure of this loss.

Under this perspective:

- Both lump-sum and periodic payments are merely different methods of disbursing compensation for this same, singular damage.

- Periodic payments, with the CCP Art. 117 adjustment mechanism, are seen as a way to more accurately realize the true value of that initially fixed damage over time, correcting for the inherent uncertainties of upfront, long-term prediction.

- If the damage is fundamentally fixed at the time of the tort, and the victim was entitled to compensation for a full working life (barring foreseeable early death), then the victim's subsequent unrelated death doesn't diminish that original entitlement. The payments, representing that entitlement, could logically continue to their heirs.

- The supplemental opinion's suggestion to convert to a lump sum post-death is then seen not as a re-evaluation of the total damage, but as a pragmatic way to finalize a payment schedule for an already established quantum of loss.

Lens 2: The "Continuously Materializing Loss" Perspective

This alternative, more traditional view, distinguishes more sharply between the impairment of labor capacity (an immediate, fixed loss) and the loss of specific income that would have been earned in successive periods.

Under this perspective:

- Periodic payments are primarily seen as compensating for the loss of specific income as it would have been earned, period by period. The payments track the damage as it "materializes."

- If the victim dies from an unrelated cause, the actual loss of future specific income for periods after death ceases. The logic here would be that one cannot lose income they would no longer be alive to earn.

- Compensation post-death might then shift. Periodic payments for specific income loss would stop. However, there could still be a claim for any uncompensated portion of the value of the lost labor capacity itself, viewed as a capital asset, perhaps payable as a lump sum to the heirs.

- The supplemental opinion's mechanism for converting to a lump sum upon the victim's death aligns quite closely with this outcome, providing a procedural route to what this perspective would see as a substantively justified adjustment.

Navigating the Nuances

The Supreme Court’s judgment navigates complex territory. While it states that periodic payments cover the "same damage" as a lump sum, which is fixed at the time of the tort, it also embraces the idea that periodic payments can be adjusted based on future changes. This raises questions:

- If periodic payments are adaptable to future changes in, for example, wage levels or the victim's condition (had they lived), why is the victim's death (the most definitive change) not treated as a factor that redefines the end-point of the original damage period for income loss itself, unless it was foreseeable at the time of the accident? The Court's answer lies in maintaining consistency with the principle established for lump-sum payments: the tortfeasor should not gain a windfall from an unrelated, unforeseeable death. The entitlement to compensation for a full working life is established at the tort, barring specific prior knowledge of a shortened lifespan.

- The judgment creates a distinction: the duration of the working life is normatively set (e.g., 18 to 67) and generally not affected by a later, unrelated death. However, the amount of loss within that period can be subject to adjustment via CCP Art. 117 if circumstances change significantly (e.g., inflation, deflation, or changes in disability, though the latter is moot if the victim dies). This approach suggests that the "value" of the lost working life is a core component of the damage, while the periodic amounts are the means of its expression, which can be fine-tuned.

- An interesting point arises if one strictly follows the "single, fixed damage" idea for lump sums. If a large lump sum is paid based on predictions, and actual subsequent economic conditions (e.g., severe deflation) or an unrelated earlier death (which, under the ruling's logic for lump sums, doesn't reduce the initial calculation unless predictable) mean the victim (or their estate) received "more" than what future reality would have dictated, this overpayment is generally not recoverable due to the finality of judgments. The Court's approach to periodic payments, while allowing for adjustments for unfolding realities, still anchors the period of compensation to the initial assessment of working life, promoting a degree of certainty for the victim.

Commentators have noted that the desire to ensure victims receive compensation for a "full" working life, irrespective of later unrelated misfortunes, while also allowing periodic payments to adapt to evolving economic realities, creates a sophisticated, albeit complex, legal framework. The supplemental opinion's proposed solution for post-death scenarios appears to offer a pragmatic route to balance the continuation of the underlying entitlement with the practicalities of closing out a long-term payment obligation.

It is also noteworthy that the judgment implicitly supports the idea that different types of future damages might be treated differently under periodic payment schemes. For instance, future nursing care costs, if awarded periodically, would naturally cease upon the victim's death because the need for care ceases. This is distinct from lost future earnings, which are seen as compensation for the loss of an earning capacity over a defined period. The Supreme Court's reasoning in the present case, even from the "single damage event" perspective, would likely accommodate such a distinction for care costs, suggesting that the nature of the specific head of damage remains crucial.

Conclusion: A Step Towards Dynamic and Fair Compensation

The Supreme Court's July 9, 2020 decision is a pivotal moment in Japanese tort law concerning compensation for long-term lost earnings. It firmly establishes the availability of periodic payments for such losses, emphasizing the system's goals of achieving fair and reality-congruent compensation. Crucially, it holds that a victim's subsequent, unforeseeable death does not automatically truncate the established period of compensation, thereby upholding the principle that the tortfeasor's liability is fixed based on the circumstances at the time of the unlawful act and the projected losses therefrom.

While the judgment affirms these key principles, the supplemental opinion and the ensuing legal discourse highlight the ongoing considerations in balancing the theoretical underpinnings of damage calculation with practical administration and fairness to all parties. The possibility for a liable party to seek a conversion to a lump sum post-victim-death, via a modification lawsuit, suggests a pathway that respects the original judgment's determination of the loss period while allowing for a practical conclusion to the payment obligation.

This ruling underscores a commitment to a more dynamic approach to compensation, one that acknowledges the uncertainties of the distant future while striving to ensure that victims of serious negligence receive the full measure of damages to which they are entitled.