Navigating the Digital Shift: Key Changes to Japan's Code of Civil Procedure for International Businesses

TL;DR

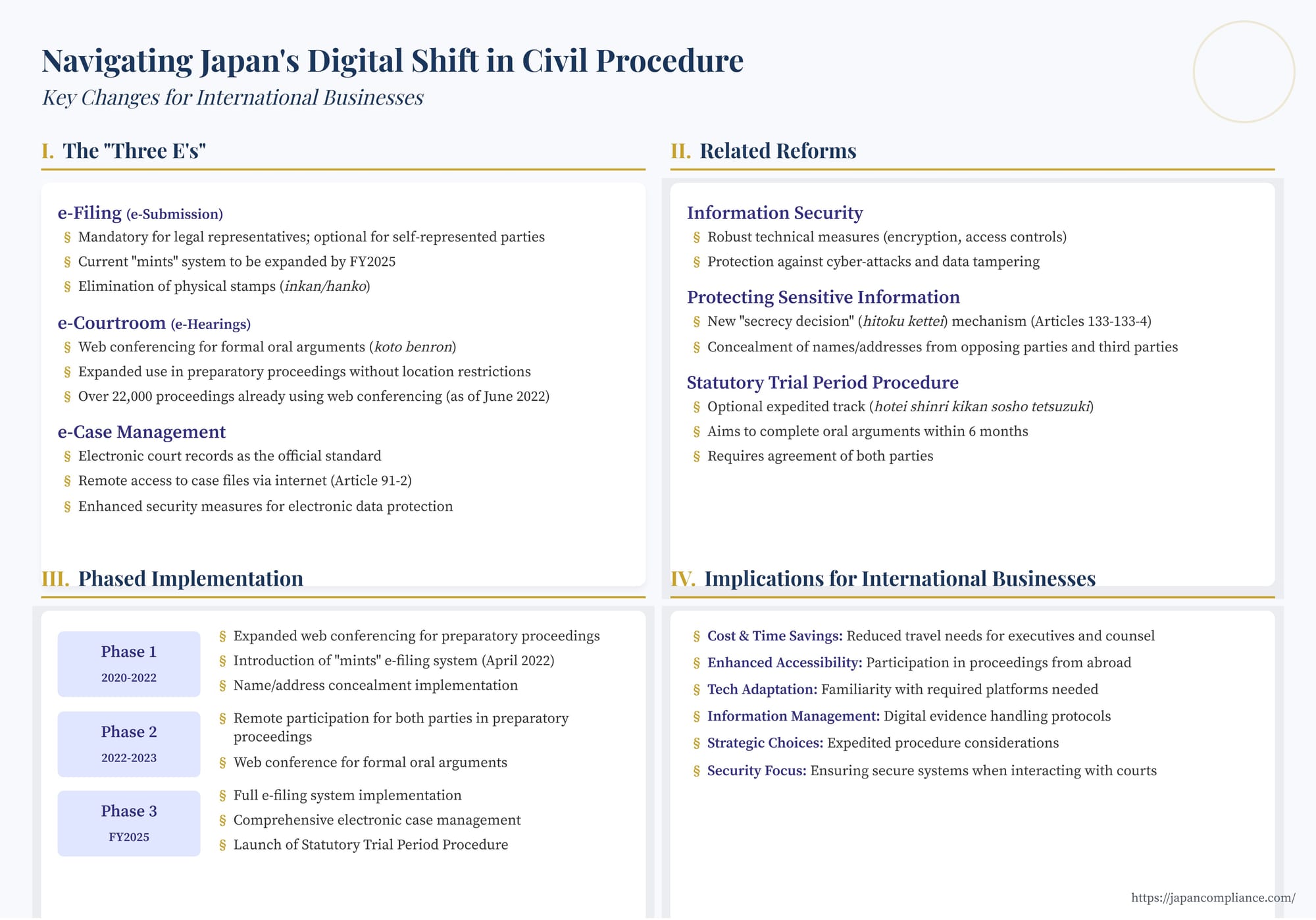

Japan’s 2022 civil-procedure amendments launch a sweeping “digital shift”: mandatory e-filing for lawyers, remote hearings via web conference, and full electronic case records. Phased through FY2025, the reforms promise faster, more accessible litigation but demand new tech readiness and data-security measures from international businesses.

Table of Contents

- The Core Components: Embracing the “Three E’s”

- e-Filing (e-Submission)

- e-Courtroom (e-Hearings)

- e-Case Management

- Related Reforms and Considerations

- Information Security

- Protecting Sensitive Information (Name/Address Concealment)

- Statutory Trial Period Procedure (Expedited Track)

- Phased Implementation and Preparation

- Practical Implications for International Businesses

- Conclusion: A System in Transition

Japan's civil justice system is undergoing a significant transformation. Driven by the need for greater efficiency, accessibility, and alignment with global digital trends, comprehensive amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure were enacted in May 2022 (Act No. 48 of 2022). This "digital shift" aims to modernize court procedures fundamentally, moving away from a predominantly paper-based system towards integrated IT solutions. For international businesses operating in Japan or engaging in cross-border litigation involving Japanese counterparts, understanding these changes is crucial. The reforms touch upon nearly every aspect of civil litigation, from initiating lawsuits and submitting documents to attending hearings and managing case records.

This overhaul isn't merely about replacing paper with electronic files; it represents a rethinking of how civil disputes are managed and resolved. The goals are ambitious: streamline processes, reduce the time and cost associated with litigation, enhance access to justice (particularly for those geographically distant from courts), and improve the overall user experience. While the full implementation is phased over several years, reaching completion by FY2025, key components are already being rolled out or are imminent. This article explores the core elements of Japan's civil procedure digitalization, focusing on the practical implications for businesses involved in the Japanese legal system.

The Core Components: Embracing the "Three E's"

The foundation of Japan's judicial IT reform rests on three pillars, often referred to as the "Three E's": e-Filing, e-Courtroom, and e-Case Management.

- e-Filing (e-Submission): Towards Paperless Litigation

Perhaps the most fundamental change is the move towards online submission of court documents. The amended Code broadly permits parties to file petitions, briefs, evidence, and other submissions electronically via a dedicated court-managed system.- Mandatory Electronic Filing for Professionals: A significant aspect of this reform is the mandatory requirement for appointed legal representatives (primarily attorneys and judicial scriveners – shiho shoshi) to use the electronic filing system. While exceptions exist for system failures or other unavoidable circumstances attributable to the court system, the default expectation for represented parties is digital submission.

- Optional for Self-Represented Litigants: Parties without legal representation (litigating pro se) can still file documents in paper format. In such cases, the court clerk will be responsible for digitizing these documents and saving them to the electronic case file. However, the system aims to encourage electronic filing even for these parties, and support mechanisms are being considered to address the "digital divide" and assist those unfamiliar with IT procedures.

- System Infrastructure: Japan has already begun experimenting with electronic filing systems. The "mints" (Minji Saiban Shorui Denshi Teishutsu System) was introduced in April 2022 in select courts (including parts of Tokyo and Osaka District Courts, the Intellectual Property High Court, and others) for submitting certain documents like preparatory briefs and evidence exhibits (as copies) in cases where both parties are represented and agree to use the system. This initial phase allows PDF, Word, and Excel file uploads (up to 50MB total per submission). The experience gained from mints will likely inform the development of the more comprehensive system required for full implementation by FY2025. The final system is expected to be web-browser-based, though details regarding specific functionalities like format input versus API integration are still under consideration.

- Elimination of Physical Stamps (Inkan/Hanko): Traditionally, court documents required physical seals. Electronic filing necessitates a move away from this, relying instead on system-based authentication, although specific details regarding requirements like electronic signatures are expected to be outlined in Supreme Court rules, with a tendency towards minimizing user burden.

- e-Courtroom (e-Hearings): Redefining Court Attendance

The reforms significantly expand the possibilities for remote participation in court proceedings, reducing the need for physical travel to the courthouse.- Web Conferencing for Oral Arguments: A major development is the explicit authorization for parties to participate in formal oral argument sessions (koto benron) via web conferencing (video and audio). Previously, oral arguments required physical presence. Under the new rules (Article 87-2), the court can permit web conference participation when deemed appropriate after hearing the parties' opinions. Participants joining remotely are legally considered to have "appeared" at the hearing.

- Expanded Use in Preparatory Proceedings: While telephone and video conferencing were already used to some extent in preparatory proceedings (benron junbi tetsuzuki or shomen ni yoru junbi tetsuzuki), the amendments remove restrictive requirements, such as the need for at least one party to be physically present for benron junbi tetsuzuki or the "remote location" requirement. Now, if the court deems it appropriate, both parties can participate remotely via web conference or even telephone conference in these crucial stages focused on clarifying issues and evidence. This flexibility was trialed during the COVID-19 pandemic using commercial platforms like Microsoft Teams and proved popular, paving the way for its formal incorporation. In June 2022 alone, over 22,000 preparatory proceedings reportedly utilized web conferencing.

- Practical Considerations: The shift to remote hearings brings benefits like reduced travel time and costs, easier scheduling, and improved access for parties with mobility issues or those located far from the court. However, it also raises practical challenges:

- Identity Verification: Ensuring the person participating remotely is indeed the party or their authorized representative.

- Environment: Maintaining the formality and integrity of proceedings when parties participate from diverse locations (offices, homes). Courts may need rules regarding suitable environments to prevent distractions or confidentiality breaches.

- Technology: Ensuring stable internet connections and adequate equipment for all participants.

- Unauthorized Recording: Preventing participants from recording proceedings without permission (which is generally prohibited under court rules).

- Functionality: Determining the appropriate use of web conference features like chat or screen sharing within the formal structure of different hearing types. While useful in preparatory stages for sharing documents or clarifying points, their role in formal oral arguments might be more limited.

- e-Case Management: Digital Court Records

The move to electronic filing naturally leads to the digitization of the entire court record.- Electronic Record as Standard: Electronically filed documents become the official record. Paper documents submitted by unrepresented parties are scanned and incorporated by the court clerk (Article 132-12). Judgments, court orders, and hearing minutes will also be generated and maintained electronically.

- Online Access and Viewing: A key benefit is the planned ability for parties and other authorized individuals (e.g., third parties with a legal interest) to access and view the electronic case file remotely via the internet (Article 91-2). This eliminates the need to visit the courthouse physically to inspect paper records.

- Security and Confidentiality: Transitioning to electronic records necessitates robust security measures to protect against unauthorized access, data breaches, and tampering. This includes securing the court's servers and ensuring secure authentication for users accessing the system. Confidentiality concerns also arise, particularly regarding sensitive information within the record, leading to related reforms discussed below.

Related Reforms and Considerations

Beyond the core "Three E's," the digitalization package includes other significant changes and necessitates careful thought regarding security and privacy.

- Information Security:

The shift to a digital environment brings inherent security risks. The amendments were developed with information security as a key consideration. Discussions during the legislative process highlighted the need for security levels comparable to other governmental and private sector systems handling sensitive information. Concerns include cyber-attacks, data leakage (intentional or accidental), unauthorized access, data tampering, and denial-of-service attacks impacting the system's availability. Robust technical measures (firewalls, encryption, access controls, monitoring) and organizational measures (user training, clear protocols) are essential. The specific security standards and protocols will be detailed in Supreme Court rules and system design, but the foundational legislation acknowledges the criticality of protecting the integrity and confidentiality of digital court proceedings. - Protecting Sensitive Information (Name/Address Concealment):

Coinciding with the IT reforms, a new system allows parties to request that their name, address, or other identifying information be kept confidential from the opposing party and third parties accessing the court record (Articles 133 to 133-4). This was primarily motivated by the need to protect victims of domestic violence, stalking, or sexual offenses from secondary harm that could result from the abuser gaining access to their current location through court filings.- Procedure: A party must file a motion demonstrating that disclosure of the information would pose a significant risk of harm to their social life. If granted, the court issues a "secrecy decision" (hitoku kettei) and designates alternative identifiers (e.g., using only initials or a generic location) to be used in publicly accessible parts of the record. Access to the original, unredacted information is then restricted to the party who filed it and the court.

- Balancing Interests: This system requires balancing the need for protection against the opposing party's right to due process (knowing the identity of their accuser/opponent) and the principle of open justice (public access to court records). The opposing party or an interested third party can petition to cancel the secrecy decision if the requirements are no longer met or were lacking initially. Furthermore, if the secrecy hinders the opposing party's ability to mount an effective defense, they can apply to the court for permission to view the restricted information (Article 133-4(2)).

- Broader Implications: While designed for specific victim protection scenarios, this mechanism highlights the increasing focus on managing sensitive personal data within the court system, a concern amplified by the move to easily accessible electronic records.

- Statutory Trial Period Procedure (Expedited Track):

To address long-standing concerns about the length of civil litigation in Japan, the reforms introduce a new, optional expedited procedure (hotei shinri kikan sosho tetsuzuki) (Articles 381-2 to 381-9).- Goal: This track aims to conclude oral arguments within six months of commencement and deliver a judgment within one month thereafter.

- Opt-In: It requires the agreement of both parties to utilize this procedure. The court must grant the application unless it would unfairly prejudice one party or hinder the realization of a proper trial (e.g., in exceptionally complex cases).

- Process: The procedure emphasizes focused case management, early clarification of issues and evidence, and potentially more streamlined proceedings, although the specific rules governing its operation are yet to be fully detailed and implemented (expected by FY2025).

- Relevance: For businesses seeking faster resolution of commercial disputes, this could offer a valuable alternative to standard litigation, provided both sides agree and the case is suitable. Its success will depend heavily on the cooperation of the parties and their counsel, as well as efficient court management.

Phased Implementation and Preparation

The transition to a fully digital civil justice system is occurring in stages:

- Phase 1 (Ongoing/Recent): Utilization of existing legal frameworks to expand IT use, such as the increased use of web conferencing for preparatory proceedings (started 2020) and the introduction of the "mints" e-filing system (started April 2022). The system for concealing names/addresses is also expected to be implemented relatively early (within 9 months of the May 2022 promulgation).

- Phase 2 (Expected FY2022-FY2023): Implementation of key legislative changes enabling broader remote participation. This includes allowing both parties to participate remotely in preparatory proceedings and settlement conferences via web/telephone conferencing (within 1 year of promulgation) and enabling web conference participation in formal oral arguments (within 2 years of promulgation).

- Phase 3 (Expected FY2025): Full implementation of the comprehensive IT system, including mandatory e-filing for legal professionals, full electronic case management and record access, and the launch of the Statutory Trial Period Procedure (within 4 years of promulgation).

Courts, lawyers, and businesses need to prepare for these changes. The Supreme Court is tasked with developing detailed rules of procedure to supplement the amended Code. Law firms are adapting their workflows and investing in technology. Businesses involved in Japanese litigation should anticipate a shift towards digital communication and participation.

Practical Implications for International Businesses

The digitalization of Japan's civil procedure holds several potential implications for US and other international companies:

- Potential Cost and Time Savings: Remote participation in hearings can significantly reduce travel costs and time away from the office for executives, in-house counsel, or foreign legal advisors. Streamlined electronic filing may also reduce administrative burdens. The expedited track, if applicable, offers the promise of faster dispute resolution.

- Enhanced Accessibility: Participating in Japanese litigation from abroad becomes more feasible with expanded web conferencing options. Accessing electronic case records remotely will also improve transparency and case management for overseas parties and their counsel.

- Need for Tech Adaptation: Companies and their legal teams (both in-house and external Japanese counsel) need to be comfortable with the required technology platforms (web conferencing software, e-filing systems). Ensuring secure and reliable internet connectivity for remote hearings is essential.

- Information Management: With electronic filing and records, managing digital evidence and documents effectively becomes paramount. Clear protocols for handling sensitive information, especially in light of the new confidentiality rules, are necessary.

- Strategic Choices: The option of the Statutory Trial Period Procedure introduces a new strategic consideration at the outset of litigation – is a faster, potentially more intense process desirable and achievable given the case specifics and the opponent's likely stance?

- Navigating the Transition: As the changes are phased in, parties may encounter hybrid situations (e.g., some documents filed electronically, others on paper; some participants remote, others in person). Clarity on procedures during this transition period will be important.

- Focus on Security: Businesses must be mindful of the information security implications, ensuring their own systems are secure when interacting with court platforms and managing sensitive case data digitally.

Conclusion: A System in Transition

Japan's move to digitalize its civil justice system is a landmark reform with far-reaching consequences. By embracing e-filing, remote hearings, and electronic case management, the system aims to become more efficient, accessible, and aligned with the needs of a modern, globalized economy. While challenges related to security, the digital divide, and the adaptation of ingrained practices remain, the direction is clear. For international businesses, these changes present both opportunities for more efficient dispute resolution and the need to adapt to new digital procedures and security considerations. Staying informed about the phased rollout and preparing technologically and strategically will be key to successfully navigating Japan's evolving civil litigation landscape in the coming years.

Digitalization of Japan's Civil Litigation: Key Changes to Court Procedures and What They Mean for Businesses

Navigating Civil Litigation in Japan: A Primer for US Companies

"A Nation Averse to Litigation?" Understanding Dispute Resolution in Japan

Overview of the IT-Related Amendments to the Code of Civil Procedure (Ministry of Justice)