Navigating the Depths: Japanese Supreme Court Rules on Condominium Drainpipe Ownership

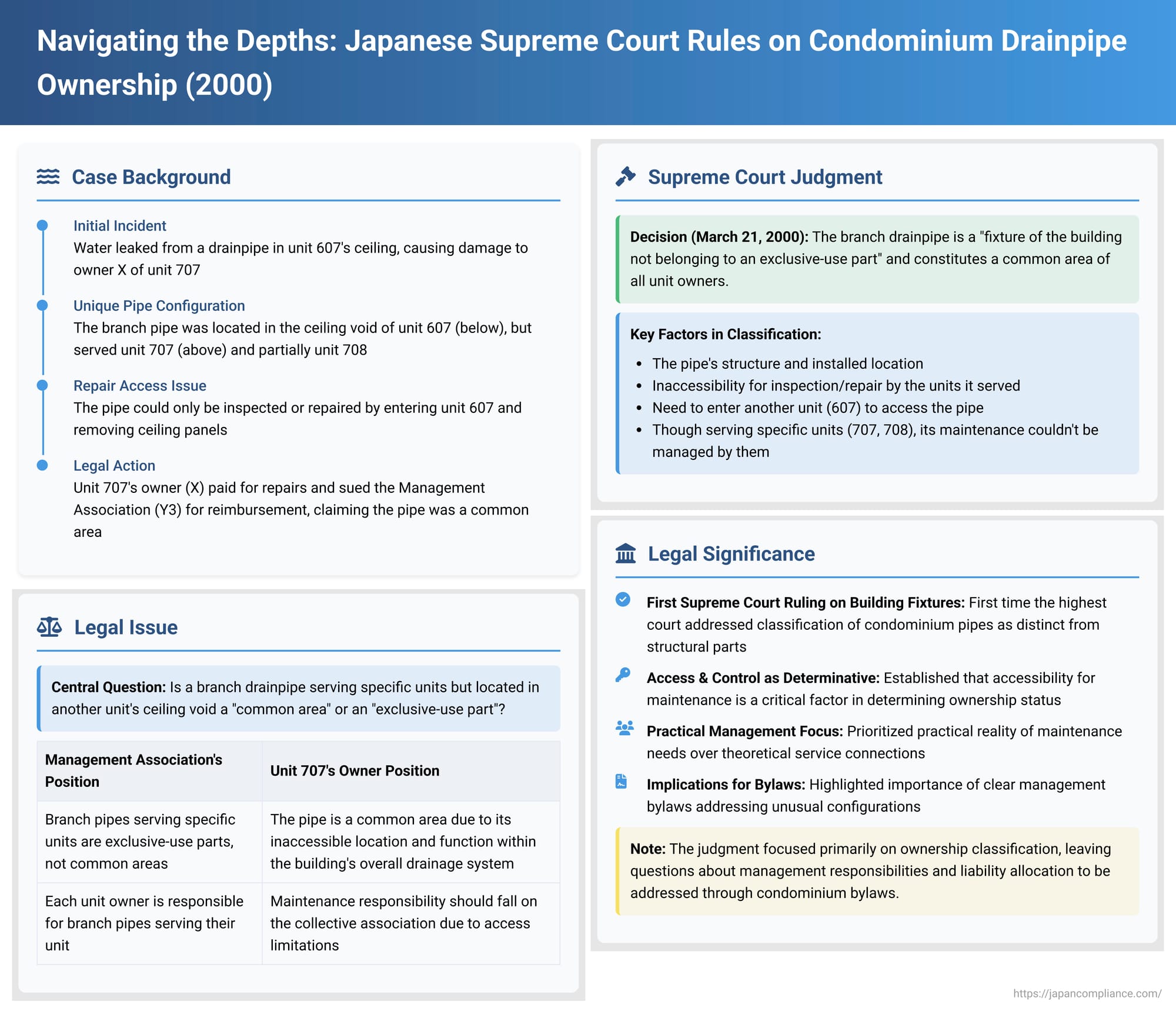

Tokyo, Japan - A significant ruling by the Supreme Court of Japan on March 21, 2000, addressed a pervasive issue in condominium living: determining whether a branch drainpipe, particularly one with an unusual configuration, constitutes an exclusive-use part or a common area. This decision offers crucial guidance on the classification of building fixtures and has lasting implications for how condominium management associations and unit owners approach responsibilities for infrastructure that serves individual units but is located in less accessible or unconventional spaces.

The Drip That Sparked the Dispute

The case originated from a water leakage incident in a condominium building. X, the owner of unit 707, experienced damage due to a leak from a drainpipe situated in the ceiling cavity of unit 607, the apartment directly below. X bore the costs of repairing the damage.

The central element of the dispute was this specific drainpipe (referred to as "the branch pipe in question"). This pipe served a dual purpose: it channeled all wastewater from X's unit 707 (kitchen, bathroom, washroom, and toilet) and also carried toilet wastewater from unit 708. Critically, this branch pipe was located in the space between the concrete structural floor slab of unit 707 and the ceiling panel of unit 607. Access for inspection or repair of this pipe was only possible by entering unit 607 and removing parts of its ceiling.

Following the incident, X initiated legal proceedings against Y1 (the owner of unit 607), Y2 (a resident of unit 607), and Y3 (the condominium's Management Association). X sought:

- A legal confirmation that the branch pipe in question was a common area belonging to all unit owners.

- A confirmation that Y1 and Y2 were not liable for the damages caused by the leak.

- Reimbursement from Y3, the Management Association, for the repair costs X had advanced, on the basis that the pipe was a common element for which the Association was responsible.

The Legal Flow: Lower Court Decisions

- The Tokyo District Court (First Instance): The District Court found in favor of X. It reasoned that the ceiling space of unit 607, where the branch pipe was located, though structurally distinct, lacked "functional independence" for unit 607. Therefore, this space itself was considered a common area. The court further noted that the branch pipe collected wastewater for multiple units and channeled it to the public sewer, indicating a common utility. Considering the practicalities of maintenance and management, the court found it more appropriate for such a pipe to be managed collectively by all unit owners. It concluded that the pipe was an appurtenance (fixture) of the entire building and did not qualify as a fixture belonging to an exclusive-use part, thus classifying it as a common area. Y3, the Management Association, appealed this decision.

- The Tokyo High Court (Second Instance): The High Court upheld the District Court's ruling, dismissing Y3's appeal. The High Court's analysis was more nuanced. It stated that in determining whether the branch pipe was an exclusive-use part or a common area, several factors needed comprehensive consideration: "the location (space) where the branch pipe was installed, the function of the branch pipe, the method of managing inspections, cleaning, repairs, etc., for the branch pipe, and its connection with the overall drainage of the building." The High Court found that:Based on these factors, the High Court concluded that while the branch pipe served specific unit owners, its location placed it outside their direct control and management. Moreover, due to its connection with the building's overall drainage, integrated management with the main drainpipe was necessary. Therefore, it was not appropriate to deem it the exclusive property of the specific unit owners it served and make them solely responsible for its maintenance. As the owner of unit 607 (the space where the pipe was located) did not use this particular pipe, there was no basis to assign it to unit 607's exclusive ownership. The High Court thus determined that a branch drainpipe serving specific unit owners, if not located within their exclusive-use part, should be treated as a common area, subject to the regulations of the Condominium Ownership Act, to ensure the maintenance and functionality of the entire building's drainage system. It was deemed a "fixture of the building not belonging to an exclusive-use part." Y3 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

- Location: The ceiling space of unit 607 where the pipe was installed belonged to unit 607's exclusive-use part.

- Function: The pipe served unit 707 entirely and unit 708 partially.

- Management & Access: Critically, owners or occupants of units 707 or 708 could not inspect, clean, or repair the pipe without entering unit 607.

- Relation to Building Drainage: Difficulties in management could arise if all pipes, including branch pipes leading to the main pipe, did not possess a unified form and material. This pointed to a greater need for holistic management of branch pipes.

The Supreme Court's Definitive Word (March 21, 2000)

The Supreme Court of Japan dismissed the appeal by Y3 (the Management Association), affirming the High Court's decision.

The Supreme Court first restated the key facts established by the lower court:

- Wastewater from unit 707 (kitchen, washroom, bath, toilet) was structured to flow through a branch pipe located in the ceiling cavity of unit 607 (the unit below), passing through the concrete structural slab of unit 707, and then into the common main vertical drainpipe. The branch pipe in question was the section located in the space between this concrete slab and the ceiling panel of unit 607.

- This branch pipe was also connected, just before joining the main pipe, to another branch pipe carrying wastewater from unit 708's toilet. No wastewater from units other than 707 and 708 flowed into it.

- Crucially, because the branch pipe was located beneath the concrete slab of unit 707, inspection and repair by the occupants of units 707 or 708 were impossible. The only way to access it was by entering unit 607 and going through its ceiling panel.

Based on this factual matrix, the Supreme Court concluded:

"Under these facts, it is reasonable to interpret that the branch pipe in question, in light of its structure and installed location, constitutes a fixture of the building not belonging to an exclusive-use part as stipulated in Article 2, Paragraph 4 of the Act on Condominium Ownership, and further constitutes a common area of all unit owners."

The Court found the High Court's judgment, which reached the same conclusion, to be legitimate and affirmed it, finding no legal error in the original verdict.

Dissecting the Decision: Key Factors and Broader Implications

This Supreme Court judgment is highly significant as it was the first time the highest court provided a clear ruling on whether a branch drainpipe, specifically one serving only certain units, belongs to an exclusive-use part or a common area. It also marked the Supreme Court's first direct pronouncement on the classification of building fixtures (like pipes, wiring, etc.), as distinct from structural parts of a building (like walls or floors), within the framework of condominium ownership. While the ruling is specific to the facts presented (a "jirei hanketsu" or case-specific judgment), it offers valuable principles for analyzing the status of similar building appurtenances.

- A Departure from Traditional Views?

Historically, a common understanding in practice, often supported by drafters of early condominium legislation, was that while main utility pipes (vertical stacks) are common areas, branch pipes that lead from an individual unit's outlets to the main pipe are typically considered part of the exclusive-use portion. This view was often based on the rationale that items within a unit owner's spatial control should be their responsibility to manage, and they should likewise bear the risks associated with those items. Indeed, post-2004 revisions to Japan's Standard Management Bylaws for Condominiums appear to maintain this general stance for typical configurations.

The Supreme Court, however, did not simply declare all branch pipes to be common or exclusive. Its decision was intricately tied to the specific circumstances of the pipe in question. - The Critical Triad: Structure, Location, and Accessibility

The Supreme Court's reasoning pivoted on three interconnected factual elements highlighted in its judgment:- Peculiar Structure/Location: The pipe was a "ceiling-run pipe" (天井配管 - tenjō haikan), installed in the ceiling cavity of the unit below the one it primarily served. This is less common than underfloor piping systems where pipes serving a unit are located beneath its own floor. This specific location—between unit 707's structural floor slab and unit 607's decorative ceiling panel—was paramount.

- Limited Service (but not exclusive to one): The pipe exclusively served units 707 and 708; no other units utilized it. This limited service distinguishes it from main pipes but doesn't automatically make it part of either 707's or 708's exclusive property given its location.

- Inaccessibility for Users (The Linchpin): The most heavily emphasized factor, both in the Supreme Court's concise reasoning and in subsequent legal analyses, was the impossibility for the owners/occupants of units 707 and 708 (the users of the pipe) to perform any inspection, maintenance, or repair without entering unit 607 and accessing its ceiling void. This lack of direct access severely undermined any notion that the pipe was under the exclusive control or management of its users.

- The Interplay of Control and Benefit

Legal scholars suggest the Supreme Court implicitly recognized that X (owner of unit 707) could not be deemed to have control over the pipe, a crucial element for exclusive ownership. Simultaneously, since the pipe did not serve unit 607, there was no basis to consider it an exclusive fixture of unit 607, despite its physical presence within the spatial confines of that unit's ceiling structure. - A Narrower Focus than the High Court?

Notably, the Supreme Court's judgment did not explicitly reference the High Court's argument about the general "necessity for integrated management" of branch pipes with the main drainage system. Some commentators interpret this omission as suggesting that the Supreme Court's ruling might be more narrowly confined to the specific facts of "ceiling piping" configurations where accessibility is a major issue. It implies that if a branch pipe, even if serving only one unit, is located such that the unit owner can access and repair it from within their own exclusive-use space without needing permission to enter another unit, it might still be classified as an exclusive-use fixture. (A subsequent Fukuoka High Court decision, for instance, found an underfloor branch pipe accessible from the unit it served to be an exclusive-use part, a finding not necessarily contradictory to the Supreme Court's framework when accessibility is considered).

Beyond Ownership: The Lingering Questions of Management and Liability

While the Supreme Court definitively classified the branch pipe in question as a common area, its ruling focused squarely on the ownership status. The judgment did not directly address the equally important practical issues of:

- Who bears the ongoing financial burden of managing, maintaining, and repairing such pipes?

- Who is liable if accidents or damage (like leaks) originate from these pipes?

Legal commentary points out that these aspects of management and liability should not be inflexibly tied to the strict legal classification of ownership. Attempting to do so could lead to impractical or unfair outcomes. Instead, these are matters best proactively addressed through clear and detailed provisions within the condominium's management bylaws (規約 - kiyaku). For example, Japan's Standard Management Bylaws (specifically, provisions like Article 21, Paragraph 2 concerning common area repairs and owner responsibilities) offer a model for how such responsibilities can be allocated, often differentiating between routine maintenance and issues arising from defects or negligence.

Practical Takeaways for Condominium Stakeholders

The March 21, 2000, Supreme Court decision serves as a vital reminder for condominium developers, management associations, and unit owners:

- Acknowledge Physical Realities: The physical layout, specific installation choices (e.g., ceiling-run vs. underfloor piping), and, critically, the accessibility of building systems and fixtures are paramount in determining their legal status and associated responsibilities.

- The Imperative of Comprehensive Bylaws: Default legal classifications may not always align with practical management needs or equitable distribution of responsibilities. Condominium bylaws should be meticulously drafted to explicitly address the ownership, management, maintenance obligations, repair cost allocation, and liability for all types of building fixtures, especially those with unusual configurations, shared service, or challenging access. Assumptions about "exclusive use" based solely on service to a particular unit can be overturned by specific structural and locational facts.

- Proactive Management: This case underscores the importance of understanding how different parts of the building's infrastructure are interconnected and how they can be accessed for maintenance and repair. This knowledge is essential for effective and fair condominium governance.

In essence, the Supreme Court's ruling on this leaky drainpipe highlights that in the world of shared condominium living, the lines between exclusive and common property are not always clear-cut, particularly when it comes to the building's vital but often hidden fixtures. The structure, location, and practical accessibility of these elements play a decisive role, pushing condominium communities to look beyond simplistic definitions and towards more nuanced, fact-based assessments and clearly articulated internal regulations.