Navigating Testamentary Intent: Japanese Supreme Court on Will Revocation and "Specific Inheritance" Clauses

Wills are fundamental legal instruments that allow individuals to dictate the distribution of their assets after their passing. However, the expression of testamentary intent can sometimes lead to complex legal questions, particularly when subsequent life events or specific phrasing in the will itself create ambiguity. The Supreme Court of Japan has, over the years, provided crucial interpretations to navigate these complexities, striving to uphold the testator's true wishes while adhering to statutory requirements. This article delves into two such significant decisions: one concerning the implied revocation of a will by subsequent conflicting life acts, and another on the precise legal effect of a will that directs specific assets "to be inherited" by certain heirs.

Part 1: When Life Changes a Will – Dissolution of Adoption and Implied Revocation (Supreme Court, November 13, 1981)

Case: Claim for Ownership Transfer Registration, Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of November 13, 1981 (Showa 56 (o) No. 310)

A will, once made, is not necessarily immutable. While formal revocation is the clearest way to change a will, Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Civil Code also recognizes that a will can be deemed revoked if it conflicts with a lifetime disposition or "other legal act" undertaken by the testator after the will was made. This provision raises an important question: what kind of "other legal act" suffices, and how broadly should "conflict" be interpreted? A 1981 Supreme Court decision explored this in the context of a devise made to adopted children whose adoptive relationship with the testator was later dissolved.

Facts of the Case: Adoption for Care, a Generous Devise, a Breach of Trust, and a Dissolution

The case involved a testator, A, and his wife, B.

- Family Background and the Need for Care: A and B had no biological children together. A did have a non-marital child, Y, who did not reside with the couple[cite: 5, 6]. Having had previous unsuccessful adoption experiences and with B suffering from ill health (a cerebral hemorrhage), A and B sought to adopt individuals who could provide them with dedicated lifelong care[cite: 5]. They approached X1 and X2 (a married couple related to B's family), the plaintiffs/appellants in this case[cite: 5].

- The Adoption Agreement and Subsequent Will: Initially hesitant, X1 and X2 agreed to the adoption after A made a significant promise: if they became his adopted children, lived with him and B, and provided them with care for the remainder of their lives, A would devise the bulk of his real estate ("the Property") to X1 and X2[cite: 5]. A also indicated that his non-marital child, Y, would only receive the specific house and land where Y was then living[cite: 5].

The adoption of X1 and X2 by A and B was legally formalized on December 22, 1973[cite: 5]. Following this, X1 and X2 moved in with A and B and began their cohabitation and caregiving duties[cite: 5]. As promised, on December 28, 1973, A executed a formal notarized will (the "Will"). This Will stipulated that:- All of A's cash and bank deposits would be devised to his wife, B[cite: 5].

- A specific house and parcel of land would be devised to his non-marital child, Y[cite: 5].

- All of A's remaining real estate (the Property in dispute) would be devised to the adopted children, X1 and X2, in equal one-half shares[cite: 5].

- A Serious Breach of Trust: In October 1974, a damaging discovery was made. X1, one of the adopted sons, along with his biological brother, had, without A's knowledge or consent, used A's real estate (part of the Property devised to X1 and X2) to secure a very substantial business debt of ¥400 million for their company by creating a revolving mortgage on it[cite: 5]. A was described as "enraged" upon learning of this unauthorized encumbrance[cite: 5]. X1 and his brother provided A with a written undertaking to have the mortgage and its registration cancelled within six months and also to repay a separate ¥15 million loan their company had taken from A. They failed to fulfill these promises[cite: 5].

- Dissolution of the Adoptive Relationship: Having completely lost trust in X1 and X2 due to this profound breach and their failure to rectify the situation, A and B requested a dissolution of the adoptive relationship with X1 and X2[cite: 5]. X1 and X2 consented to this. The adoption was formally dissolved by mutual agreement (協議離縁 - kyōgi rien) on August 26, 1975[cite: 5]. Following the dissolution, X1 and X2 moved out of A and B's home[cite: 5].

- Subsequent Care Arrangements and Testator's Death: After X1 and X2 departed, they provided no further care or support to A and B[cite: 5]. Instead, A's non-marital child, Y, and Y's spouse assumed the responsibility of caring for A and B[cite: 5]. A passed away on January 8, 1977, and his wife B died shortly after, on February 1, 1977[cite: 5].

- X1 and X2's Claim Based on the Will: Despite the dissolution of their adoption and their cessation of care, X1 and X2 filed a lawsuit against Y and A's other legal heirs. They asserted that they had acquired ownership of the Property by virtue of A's 1973 Will and sought a court order for the transfer registration of the Property into their names[cite: 5].

- Lower Court Rulings – Devise Deemed Revoked: Both the first instance court and the High Court ruled against X1 and X2[cite: 5]. These courts found that the subsequent dissolution of the adoptive relationship by mutual agreement between A (the testator) and X1/X2 (the devisees) constituted a "legal act conflicting with the prior will" within the meaning of Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code. Therefore, they concluded that the devise of the Property to X1 and X2 in A's Will had been implicitly revoked by this later act of dissolving the adoption[cite: 5]. X1 and X2 appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Dissolution of Adoption Implied Revocation of Devise

The Supreme Court dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, affirming the lower courts' conclusion that the devise had been revoked.

The Court's reasoning focused on the interpretation of Article 1023, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Code, which deals with implied revocation:

- Article 1023(1) states that if a later will conflicts with an earlier will, the earlier will is deemed revoked to the extent of the conflict.

- Article 1023(2) applies this principle mutatis mutandis when a will conflicts with a subsequent lifetime disposition or "other legal act" by the testator.

- The Supreme Court emphasized that the legislative intent (法意 - hōi) behind Article 1023(2) is to give precedence to the testator's final manifested intention as expressed in their subsequent lifetime acts.

- A "conflict" under Article 1023(2) is not limited merely to situations where the subsequent lifetime act makes the physical execution of the prior will objectively impossible. It also encompasses situations where, considering all circumstances, it is clear that the subsequent lifetime act was done with an intention inconsistent with upholding the prior will.

- In this case, the High Court had found that A made the Will devising the Property to X1 and X2 on the premise that they, as his adopted children, would provide him and his wife with lifelong care and support. This expectation was foundational to the devise.

- However, due to X1's severe breach of trust and the subsequent failure to make amends, A lost faith in X1 and X2. This directly led to the mutual agreement to dissolve the adoptive relationship. As a result of this dissolution, A and B legally and factually ceased to receive care and support from X1 and X2.

- The Supreme Court concluded that this agreed-upon dissolution of the adoptive relationship was an act carried out by A with an intention that was irreconcilable with maintaining the prior devise to X1 and X2. The devise was predicated on the adoptive relationship and the expectation of care, both of which were terminated by the dissolution.

- Therefore, the devise in the Will was deemed to have been revoked by the subsequent act of dissolving the adoption, as this later act "conflicted" with the will in the broader, substantive sense intended by Article 1023(2).

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1981 Supreme Court decision offers important insights into the implied revocation of wills:

- Broad Interpretation of "Conflict" (抵触 - teishoku): The judgment confirmed a substantive, rather than purely formalistic, interpretation of what constitutes a "conflict" under Article 1023(2) sufficient to imply revocation[cite: 6]. It's not just about the objective impossibility of executing the will, but about whether the testator's later act demonstrates a clear change of intent that is fundamentally incompatible with the prior testamentary disposition[cite: 6]. This approach aligns with an earlier Daishin'in (Great Court of Cassation) precedent from Showa 18 (1943)[cite: 6].

- "Other Legal Acts" Include Family Law Acts: The decision explicitly establishes that the "other legal acts" capable of revoking a will under Article 1023(2) are not limited to property dispositions (like selling the devised asset)[cite: 6]. They can include significant family law acts, such as the dissolution of an adoptive relationship by mutual agreement, if that act clearly manifests an intention inconsistent with a prior will benefiting the (now former) adopted child[cite: 6]. The PDF commentary suggests this was the first Supreme Court case to clearly affirm this inclusion[cite: 6].

- Primacy of Testator's Final Manifested Intention: The ruling underscores the legal system's deference to the testator's final discernible wishes. If a deliberate legal act undertaken after making a will clearly indicates a repudiation of the basis upon which a prior devise was made, that later act can take precedence and imply revocation.

- Importance of the Devise's Underlying Premise: The fact that the devise to X1 and X2 was intrinsically linked to their adoption and the expectation of lifelong care was central to the outcome[cite: 5]. When this fundamental premise was destroyed by their actions and the subsequent mutual dissolution of the adoption, the rationale for the devise, from the testator's perspective, also collapsed[cite: 5].

- Scholarly Debate and Alternative Views: The PDF commentary notes that this broad interpretation of "conflict" to include disparate legal acts (a property devise vs. a family law act of dissolution) has faced some scholarly criticism[cite: 7]. Some argue that for Article 1023(2) to apply, the "conflict" should ideally arise between acts of a similar nature (e.g., a property devise being implicitly revoked by a subsequent disposition of the same property)[cite: 7]. These critics suggest that outcomes like the one in this case might be better achieved through other legal constructions, such as interpreting the original devise as being implicitly conditional upon the continuation of the adoptive relationship and care, or potentially viewing the former adopted children's claim to the devise as an abuse of rights given their conduct[cite: 7].

This judgment highlights the dynamic nature of testamentary intent and how subsequent life events and legal acts can profoundly impact the validity of a previously executed will. It serves as a reminder of the importance of regularly reviewing and updating testamentary plans to ensure they accurately reflect one's final wishes, especially when significant changes in family relationships occur.

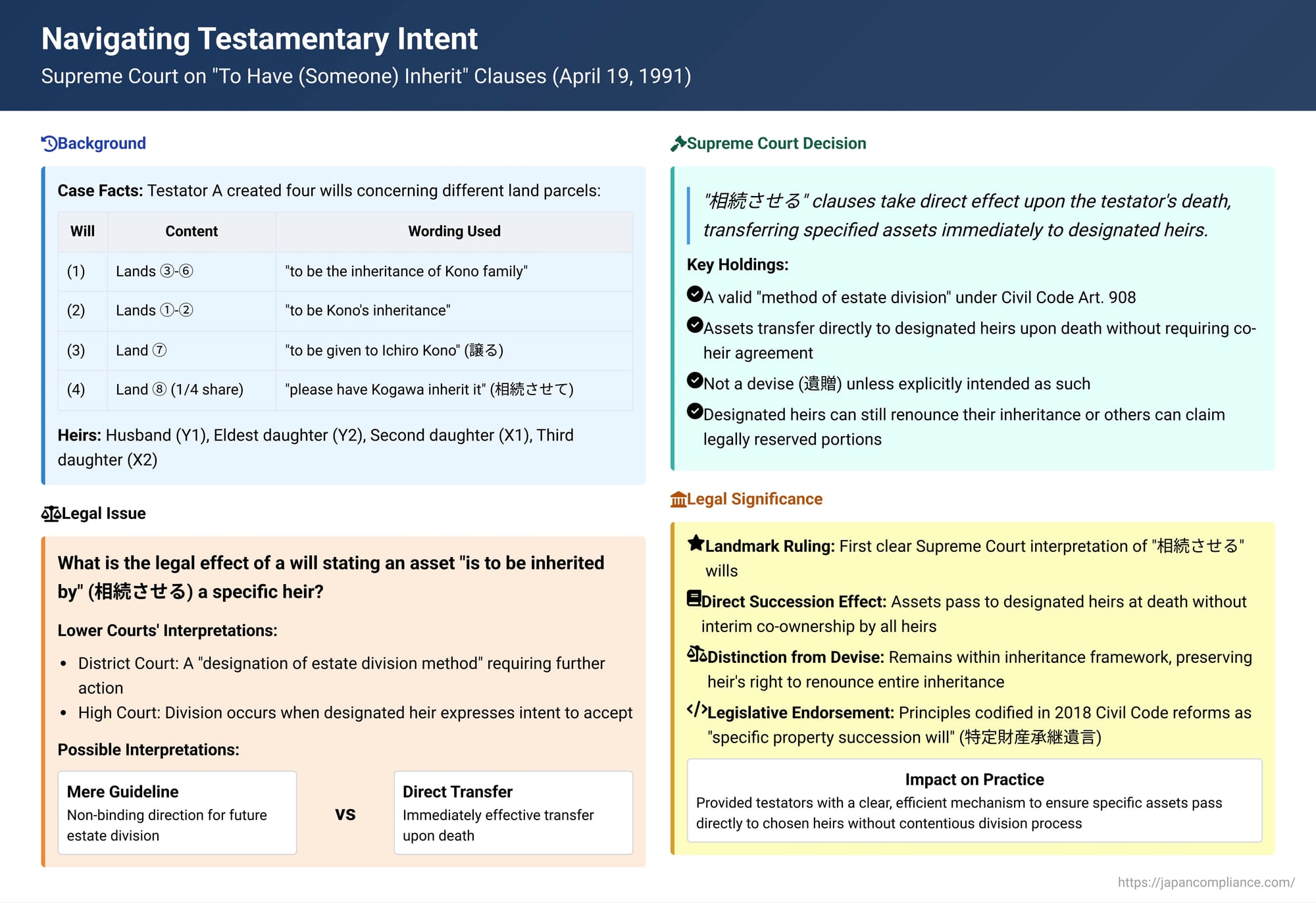

Part 2: "To Have (Someone) Inherit" – Interpreting a Testator's Specific Directive (Supreme Court, April 19, 1991)

Case: Claim for Land Ownership Transfer Registration Procedure, Supreme Court, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of April 19, 1991 (Heisei 1 (o) No. 174)

Testators sometimes use specific, seemingly straightforward phrases in their wills that can nonetheless lead to legal disputes over their precise meaning and effect. One such common phrasing in Japanese wills is when a testator directs that a particular asset "is to be inherited by" a specific heir (「相続させる」 - sōzoku saseru). Does this merely designate that heir as a recipient within the general framework of inheritance and estate division, or does it have a more direct effect, perhaps akin to a specific devise, bypassing some aspects of the usual estate division process? The Supreme Court of Japan provided a landmark interpretation of such "相続させる" clauses in its decision on April 19, 1991.

Facts of the Case: Multiple Wills with "Inherit" and "Devise" Language

The case involved the estate of A (Haru Otsuyama), who passed away on April 3, 1986. Her heirs were her husband Y1 (Taro Otsuyama), eldest daughter Y2 (Natsuko Otsuyama), second daughter X1 (Akiko Kono), and third daughter X2 (Fuyuko Kogawa). X3 (Ichiro Kono) was X1's husband.

A had created four holographic wills concerning various parcels of land (Land ① to ⑧):

- Will (1): Lands ③ to ⑥ were "to be the inheritance of the Kono family (甲野一家の相続とする - Kōno ikka no sōzoku to suru)."

- Will (2): Lands ① and ② were "to be Kono's inheritance (甲野の相続とする - Kōno no sōzoku to suru)."

- Will (3): Land ⑦ was "to be譲る (yuzuru - given/transferred/assigned) to Ichiro Kono (X3)."

- Will (4): A's 1/4 share in Land ⑧ was "please have Kogawa inherit it (甲川に相続させてください - Kōgawa ni sōzoku sasete kudasai)." (Kogawa refers to X2).

X1, X2, and X3 (the plaintiffs/appellants) filed a lawsuit seeking confirmation of their ownership or co-ownership rights in these various parcels of land based on these will provisions.

- First Instance Court Ruling:

- Interpreted Will (3) ("譲る" to X3) as a specific devise (遺贈 - izō), granting X3 ownership of Land ⑦[cite: 1].

- Interpreted Wills (1), (2), and (4) (using forms of "相続させる") as designations of the method of estate division (遺産分割方法の指定 - isan bunkatsu hōhō no shitei) under Article 908 of the Civil Code[cite: 1]. It held that because a formal estate division had not yet occurred, X1 only had a 1/6 co-ownership share in Lands ①-⑥, and X2 only had a 7/24 co-ownership share in Land ⑧ (this included X2's original statutory share plus whatever was intended for her by the will, aggregated somehow with her existing share)[cite: 1].

- High Court Ruling:

- Upheld the first instance court's interpretation of Will (3) (Land ⑦ to X3) as a devise[cite: 1].

- Interpreted "Kono family" in Will (1) to mean X1 (Akiko Kono) and her husband X3 (Ichiro Kono), treating the part for X3 (a non-heir in A's direct line for statutory purposes, though A's son-in-law) as a devise[cite: 1].

- It agreed that X1's portion of Will (1) and Wills (2) (for X1) and (4) (for X2) were designations of the method of estate division[cite: 1]. However, it uniquely reasoned that when the designated heirs (X1 and X2) filed the current lawsuit asserting their rights under these wills, this act constituted a clear expression of their intent to accept the testamentary disposition, which, when communicated to the other co-heirs (Y1 and Y2) through the lawsuit, effectively resulted in a partial estate division agreement coming into existence at that moment[cite: 1].

- Based on this, the High Court concluded that X1 owned Lands ① and ② outright and had a 1/2 co-ownership share in Lands ③-⑥; and X2 had a 1/2 co-ownership share in Land ⑧[cite: 1].

- Appeal by Y2 to the Supreme Court: Y2 (A's eldest daughter) appealed the High Court's decision concerning the rights granted to X1 (her sister Akiko Kono).

The Supreme Court's Decision: "To Have Inherit" as a Direct Method of Estate Division

The Supreme Court dismissed Y2's appeal, thereby largely upholding the High Court's ultimate allocation to X1, but it provided a far more direct and influential legal reasoning for the effect of "相続させる" (to have (someone) inherit) wills.

The Court laid down the following principles:

- Primary Goal of Will Interpretation: When interpreting wills concerning the succession of a deceased's estate, the court must respect the testator's intentions as expressed in the will document and interpret its meaning reasonably.

- Considering Testator's Circumstances: A testator makes a will considering various factors: the relationship with each heir, their current and future living situations and financial resources, and any particular connection a specific heir might have to certain estate assets[cite: 1].

- Interpreting "相続させる" (To Have Inherit):

- When a will expresses the testator's intent to "have a specific heir inherit" a particular estate asset, considering that the designated heir is already a person entitled to inherit, the testator's natural and reasonable intent should be understood as wanting that specific heir to inherit that asset directly and solely, not merely as part of a later co-owned pool to be divided with other co-heirs[cite: 1].

- Unless the wording of the will clearly indicates that a devise (遺贈 - izō, a gift effective upon death which can be made to non-heirs and has different procedural implications) was intended, or there are special circumstances requiring it to be interpreted as a devise, a "相続させる" clause should not be construed as a devise[cite: 1].

- "相続させる" Wills as a Method of Estate Division (Article 908):

- Article 908 of the Civil Code allows a testator to prescribe the method of dividing their estate by will. The very purpose of this provision is to enable a testator to direct that specific assets be succeeded to by specific heirs through inheritance[cite: 1].

- Therefore, a will stating that a specific asset is "to be inherited by" a particular heir is precisely a will that stipulates the method of dividing the estate as per Article 908[cite: 1].

- Such a directive is binding on the other co-heirs. They cannot reach a contrary estate division agreement, nor can a court order a different division in an estate division adjudication[cite: 1].

- Direct Succession Effect:

- A "相続させる" will, being a testator-defined method of estate division, creates a succession outcome equivalent to a partial estate division having been completed for that specific asset, directly attributing it to the designated heir[cite: 1].

- Unless there are special circumstances in the will indicating that such succession is contingent on the designated heir's acceptance, the specified asset passes directly to that heir by inheritance at the moment of the testator's death (when the will takes effect), without requiring any further action[cite: 1].

- The asset does not first enter a state of co-ownership among all heirs to then be formally divided.

- Remaining Rights of the Designated Heir and Other Heirs:

- Even with such direct succession, the designated heir still retains the freedom to renounce their inheritance (相続の放棄 - sōzoku no hōki). If they do so, the asset retroactively does not pass to them[cite: 1].

- Furthermore, such a directive in a will does not preclude other heirs from exercising their rights to a legally reserved portion (遺留分 - iryūbun) if the devise infringes upon it[cite: 1].

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that the High Court's ultimate conclusion regarding X1's acquisition of rights to the specified lands was justifiable (even if the High Court's reasoning about a "division agreement forming upon filing suit" was a more circuitous route than the Supreme Court's direct effect theory).

Legal Principles and Significance

This 1991 Supreme Court judgment is a landmark in Japanese inheritance law, providing a clear and authoritative interpretation of "相続させる" (to have (someone) inherit) clauses in wills.

- "相続させる" Will as a Method of Estate Division with Direct Effect: The most significant takeaway is that a will directing a specific asset "to be inherited by" a particular heir is treated as a testamentary designation of the method of estate division under Article 908, which takes direct effect upon the testator's death. The specified asset passes immediately and solely to the designated heir, bypassing the stage of co-ownership by all heirs that would typically precede a formal estate division agreement or adjudication[cite: 2].

- Rejection of Interpretation as Mere Guideline for Future Division: This ruling moved away from earlier lower court views that sometimes treated "相続させる" clauses as merely indicative of the testator's wishes to be considered in a subsequent, separate estate division process. The Supreme Court gave it a much stronger, self-executing effect[cite: 2].

- Distinction from Devises (遺贈 - Izō): While the effect of a "相続させる" clause (direct transfer of a specific asset to a specific person upon death) is very similar to that of a specific devise, the Supreme Court was clear that it should be interpreted as an act within the framework of inheritance and estate division rules applicable to heirs, not as a devise, unless a devise is clearly intended or special circumstances warrant it[cite: 1, 2]. This distinction is crucial:

- Identity of Beneficiary: "相続させる" is typically used for statutory heirs. Devises can be made to anyone, including non-heirs.

- Legal Framework: Treating it as a method of division for heirs keeps it within the "inheritance" paradigm. For example, the designated heir can still renounce the entire inheritance (including the specified asset), which would not be the case if it were a simple devise they accepted[cite: 2]. If it were a devise, accepting the devised asset would generally imply acceptance of heirship (if the devisee is also an heir), but renouncing the devise itself is different from renouncing the status of heir. The Supreme Court's interpretation ensures that the ability to renounce the entire inheritance is preserved.

- Practical Advantages (Historical and Conceptual): The PDF commentary explains that historically, "相続させる" wills had practical advantages in terms of registration procedures and registration taxes compared to devises to heirs[cite: 2]. While some of these tax and procedural distinctions have been reduced by later legal reforms (e.g., registration tax for inheritance and devise to an heir are now similar; registration by a sole heir-devisee is now easier [cite: 2]), the conceptual difference remains: a "相続させる" will is fundamentally an act of partitioning the estate among those entitled to inherit, reflecting the testator's specific plan for this internal distribution[cite: 2, 3].

- Binding on Other Heirs: The testator's designation is binding. Other heirs cannot agree to a different division of that specific asset, nor can the Family Court order one, unless the "相続させる" clause itself is invalid (e.g., due to infringing a legally reserved portion beyond permissible limits, or if the designated heir renounces)[cite: 1].

- Statutory Endorsement in Later Civil Code Reforms: The principles established by this Supreme Court judgment have been so influential that they were effectively codified and clarified in later amendments to the Civil Code. The 2018 reforms (effective 2019) introduced the term "specific property succession will" (特定財産承継遺言 - tokutei zaisan shōkei igon) in Article 1014, Paragraph 2, to describe a will that, as a method of estate division, directs a specific estate asset to be succeeded to by one or more co-heirs[cite: 2]. This legislative endorsement affirms the direct succession effect recognized by the 1991 Supreme Court decision.

- Continued Relevance of Testator's Intent: The judgment heavily emphasizes that the interpretation must be based on the testator's rational intent, considering all relevant circumstances, including family relationships and the financial situations of the heirs[cite: 1, 3]. This allows for a nuanced understanding rather than a rigid application of the phrase.

- Interaction with Legally Reserved Portions and Renunciation: The Court explicitly noted that this direct succession effect does not negate an heir's right to renounce the inheritance entirely, nor does it prevent other heirs from making claims for their legally reserved portions (遺留分) if the "相続させる" disposition infringes upon them[cite: 1, 2]. (Under the current law, an infringement of a legally reserved portion typically leads to a monetary claim against the recipient, not a direct claim to the asset itself [cite: 2]).

- Registration Against Third Parties (A Broader Context): While this case focused on the effect among heirs, the PDF commentary links it to the broader issue of registration against third parties. If an asset passes directly to an heir via a "相続させる" will, questions arise about perfecting this title against third parties who might acquire conflicting interests from other heirs. The commentary discusses how the 2018 Civil Code amendment (Article 899-2) now generally requires registration if an heir acquires rights exceeding their statutory share through such a will, in order to assert those excess rights against third parties[cite: 4]. This creates a balance between respecting the testator's specific directions and ensuring transactional security[cite: 4].

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1991 decision profoundly shaped the understanding of "相続させる" (to have (someone) inherit) wills in Japan. By interpreting such clauses as a testator's binding designation of the method of estate division with direct effect upon death, the Court provided a clear mechanism for testators to ensure specific assets pass to chosen heirs without the need for a subsequent, potentially contentious, estate division process for those assets. This approach respects the testator's intent to achieve a swift and certain transfer within the framework of inheritance, while still preserving the fundamental rights of heirs, such as the ability to renounce the inheritance or claim their legally reserved portions. The principles of this judgment have since been reinforced by legislative reforms, solidifying its importance in Japanese succession law.