Navigating "Successor Liability" in Japanese Judgments: The Rights of a Bona Fide Purchaser

In the realm of civil litigation, a judgment rendered between two parties can sometimes extend its effects—both its binding factual and legal determinations (res judicata) and its enforceability—to third parties who succeed to the rights or obligations of the original litigants. Japanese law provides for such extensions, notably against those who become successors after the conclusion of oral arguments in a lawsuit. However, complexities arise when such a successor has their own independent legal defenses against the claim. A pivotal 1973 Supreme Court of Japan decision shed light on this intricate interplay, particularly safeguarding a bona fide purchaser who acquired property subject to a prior, unexecuted judgment.

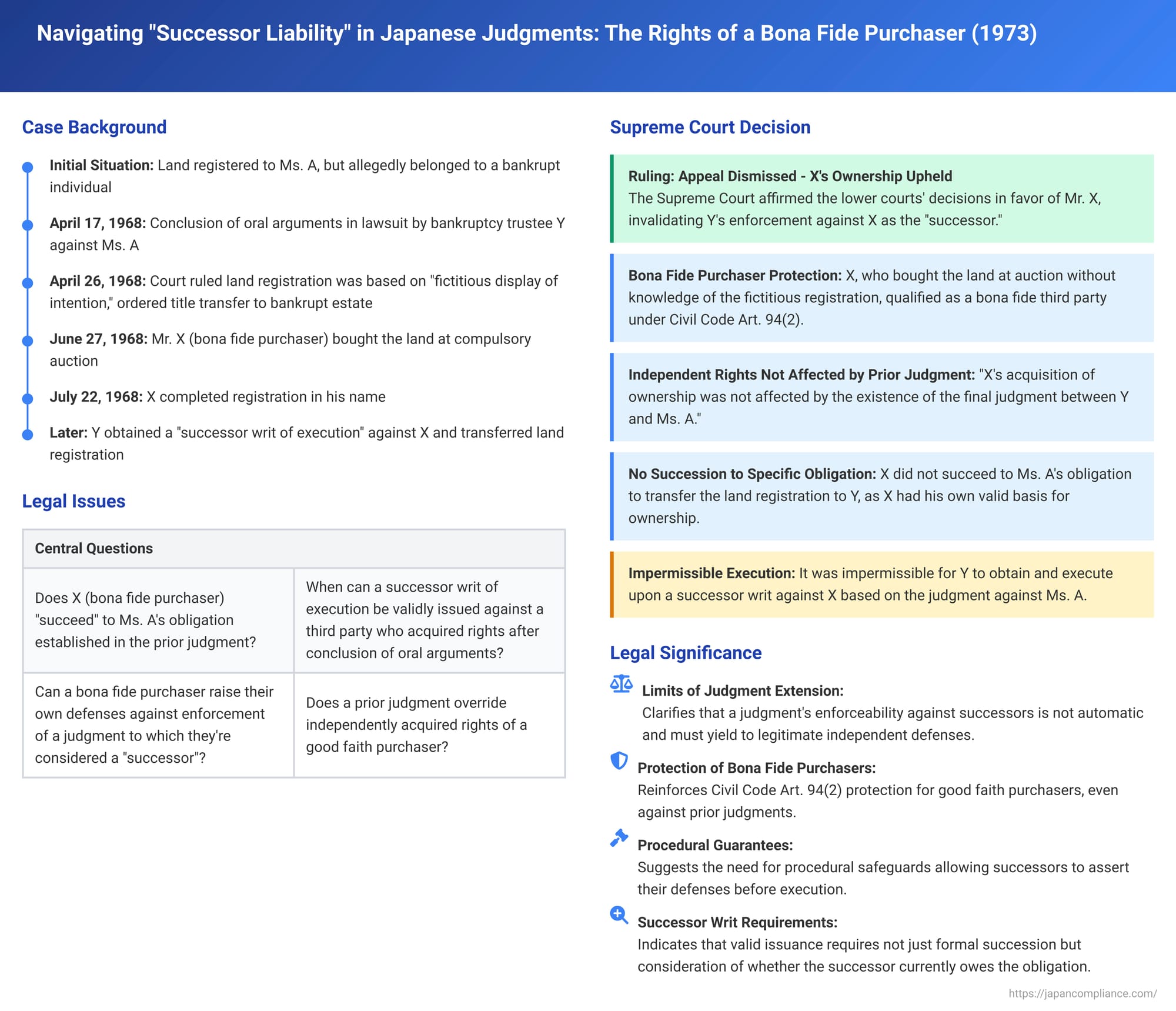

This article delves into the Supreme Court's ruling of June 21, 1973 (Showa 47 (O) No. 198), which addressed the enforceability of a judgment against a successor in interest and the successor's right to assert their own defenses.

Background of the Dispute

The case involved a parcel of land. Initially, the land was registered in the name of Ms. A. However, Mr. Y, acting as the bankruptcy trustee for the original "true" owner of the land, filed a lawsuit (the "prior suit") against Ms. A. Y alleged that the registration in Ms. A's name was the result of a "fictitious display of intention" (通謀虚偽表示 - tsūbō kyogi hyōji) between the bankrupt individual and Ms. A, meaning it was a sham transaction intended to deceive, and that the land truly belonged to the bankrupt estate. Consequently, Y sought a court order compelling Ms. A to transfer the land registration to the bankrupt estate for the purpose of "true name recovery" (i.e., to reflect the actual ownership).

The oral arguments in this prior suit between Y and Ms. A concluded on April 17, 1968. On April 26, 1968, the court ruled in favor of Y, ordering Ms. A to transfer the title. This judgment became final and binding shortly thereafter.

Meanwhile, Mr. X, being unaware of the dispute between Y and Ms. A or the underlying fictitious nature of Ms. A's registration, participated in a compulsory auction concerning the said land, which was being sold to satisfy debts owed by Ms. A. On June 27, 1968—importantly, after the conclusion of oral arguments in the prior suit between Y and Ms. A—Mr. X successfully bid for the land. He completed the ownership registration in his name on July 22, 1968.

Subsequently, Y, armed with the final judgment against Ms. A, obtained a "successor writ of execution" (承継執行文 - shōkei shikkōbun) against Mr. X. This type of writ allows a judgment obtained against an original party to be enforced against their successor in interest. Based on this successor writ, Y proceeded to have the land registration transferred from Mr. X to Y (representing the bankrupt estate).

In response, Mr. X filed a new lawsuit (the "current suit") against Y. Mr. X sought a court declaration confirming his ownership of the land and an order compelling Y to transfer the registration back to him for true name recovery. The lower courts ruled in favor of Mr. X. Mr. Y then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision

The Supreme Court dismissed Mr. Y's appeal, upholding the decisions of the lower courts in favor of Mr. X. The core of the Supreme Court's reasoning was as follows:

- Protection of the Bona Fide Third Party: The Court affirmed that the registration of the land in Ms. A's name was indeed based on a fictitious display of intention between her and Mr. Y's bankrupt. However, under Article 94, Paragraph 2 of the Japanese Civil Code, the nullity of such a fictitious act cannot be asserted against a bona fide third party (a third party who was unaware of the fictitious nature and acted in good faith). Mr. X, having acquired the land at a compulsory auction without knowledge of the fictitious registration, qualified as such a bona fide third party. Therefore, Mr. X validly acquired ownership of the land.

- Effect of the Prior Judgment on the Bona Fide Successor: The Supreme Court stated unequivocally that Mr. X's acquisition of ownership was "not affected by the existence of the final judgment between Y and Ms. A." This is a critical point: the prior judgment against Ms. A did not automatically override Mr. X's independently acquired rights as a bona fide purchaser.

- No Succession to the Specific Obligation: Consequently, the Court found that Mr. X did not succeed to Ms. A's obligation to transfer the land registration to Mr. Y (which was the obligation established by the Y vs. A judgment). Because X had his own valid basis for ownership (as a bona fide purchaser), he was not merely stepping into Ms. A's shoes with respect to the specific duty decreed in the prior judgment.

- Impermissibility of Execution against the Successor: Given that Mr. X did not inherit Ms. A's specific transfer obligation in a way that Y could enforce against him, the Court concluded that it was impermissible for Y to obtain a successor writ of execution against Mr. X based on the judgment against Ms. A and to execute upon it.

- Illegality of Y's Registration: As a result, Mr. Y's action of using the improperly obtained successor writ to transfer the land registration into his name was deemed illegal. The registration secured by Y was therefore void.

Significance and Analysis of the Decision

This 1973 Supreme Court judgment is highly significant as it clarifies the limits on extending the effects of a judgment to successors in interest, especially when those successors possess their own substantive defenses. The PDF commentary provides a detailed analysis of the decision's implications:

1. Clarification on Unlawful Execution against Successors

The ruling clearly establishes that compulsory execution based on a successor writ of execution is unlawful if the writ was issued without considering the successor's own independent defenses. This underscores that the process of extending enforceability is not merely administrative but must respect substantive rights.

2. Successor's Right to Assert Independent Defenses

A crucial takeaway is that a third party who becomes a successor to a judgment debtor after the conclusion of oral arguments in the original lawsuit (a "successor after conclusion of oral arguments" as per Article 115(1)(iii) of the Code of Civil Procedure) is not barred from asserting their own defenses regarding the inherited obligation. They can do so in a subsequent lawsuit, as Mr. X did here.

3. Interplay of Res Judicata and Executory Force Extension

The case touches upon two distinct but related concepts:

- Extension of Res Judicata: This concerns the binding effect of the findings in the prior suit (Y vs. A) on the successor (X). Generally, a successor after the conclusion of oral arguments cannot re-litigate the merits of the claim as it existed between the original parties at the time oral arguments closed in the prior suit. The purpose of extending res judicata is to protect the vested rights of the party who won the prior suit. So, X could not argue, for example, that Ms. A's registration wasn't fictitious in relation to Y.

- Extension of Executory Force: This concerns the ability to enforce the prior judgment against the successor using a successor writ of execution. This was the direct issue in Y's execution against X.

The Supreme Court's decision means that while res judicata from the Y vs. A judgment might prevent X from challenging the finding that Ms. A owed an obligation to Y at that time, it does not prevent X from raising a new defense that arose relevant to X after the conclusion of oral arguments in the Y vs. A suit. Mr. X's status as a bona fide third party under Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2 was precisely such a defense, shielding him from the consequences of the fictitious transaction. The Court's statement that X's ownership was "not affected by the existence of the final judgment between Y and A" strongly supports this.

4. Conditions for Issuing a Successor Writ of Execution

The judgment implies that for a successor writ of execution to be validly issued against a party like X, it's not enough that X is a "successor" in a general sense. The successor must also currently owe the specific obligation to the judgment creditor, taking into account any independent defenses the successor might have. This aligns with what legal scholars call the "substantive theory" for writ issuance.

The PDF commentary discusses various academic theories regarding the issuance of successor writs:

- Rights Ascertainment Theory (権利確認説 - kenri kakunin setsu): A successor writ may be issued if succession and the current obligation are prima facie (on first appearance) demonstrated. The successor can then challenge the writ's legitimacy through an "action of objection to the grant of a writ of execution" (民事執行法34条 - Civil Execution Act Art. 34).

- Burden of Suing Shifting Theory (起訴責任転換説 - kiso sekinin tenkan setsu): A successor writ is issued if the fact of succession (of legal status) is proven. If the successor has their own defenses (like X's bona fide status), they must then take the initiative to file an "action of objection to claim" (民事執行法35条 - Civil Execution Act Art. 35) to prevent enforcement.

The commentary suggests that the "Burden of Suing Shifting Theory" is currently influential in Japan. This theory emphasizes that the writ-issuing authority (a court clerk or judge) is not equipped to conduct a full substantive review of whether the claim still exists against the successor, especially considering potential new defenses. Such substantive issues are more appropriately handled in an action of objection to claim. This aligns with a 1977 Supreme Court precedent stating that objections concerning the existence of the claim against the successor are grounds for an action of objection to claim, not an action concerning the writ itself.

5. Procedural Guarantees for the Successor

The "substantive theory" (which the 1973 judgment seems to lean towards for the specific facts) and the "rights ascertainment theory" effectively place a burden on the judgment creditor (Y) at the writ issuance stage to address, or at least for the system to consider, the non-existence of the successor's (X's) independent defenses. This is particularly important in cases like this one, involving an obligation to register title, where execution can be completed swiftly, potentially before the successor has a practical opportunity to file an action of objection to claim.

However, placing this burden on the creditor can be considered harsh, as the creditor would not typically bear the burden of disproving a successor's unique defenses if they were to file a new lawsuit against the successor to obtain a fresh title of obligation. In many other types of execution (e.g., eviction of a successor occupant), the successor usually has a viable opportunity to raise their defenses through an action of objection to claim.

6. Successor Execution for Registration Duties: A Special Case?

The "Burden of Suing Shifting Theory," in its traditional formulation, was hesitant to allow successor execution for obligations involving registration of title due to the perceived lack of procedural guarantees for the successor before execution completes.

The PDF commentary suggests that even under this theory, successor execution for registration duties could be permissible. However, to ensure fairness, the successor should be afforded an opportunity—perhaps by analogy to Article 177, Paragraph 3 of the Civil Execution Act (which deals with execution against heirs for inherited property)—to submit documents proving non-succession or, crucially, to file an action of objection to claim to assert their own defenses within a certain period before the writ is finalized or executed. Had such a procedure been followed, allowing X an opportunity to raise his bona fide purchaser defense before Y's execution, the outcome might have been different at an earlier stage. In the absence of such an opportunity, the execution against X based on the successor writ was deemed unlawful.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 1973 decision provides vital protection to successors in interest, like bona fide purchasers, who possess independent substantive defenses against a claim established by a prior judgment. It highlights that the extension of a judgment's enforceability to a successor is not automatic and must yield to the successor's legitimately acquired rights. While the judgment debtor in the original suit (Ms. A) was bound by the prior judgment, Mr. X, who subsequently acquired the property in good faith, was entitled to the protection of Civil Code Article 94, Paragraph 2. The Court correctly found that Y could not use a successor writ of execution to circumvent X's superior rights.

This case underscores the careful balance Japanese law attempts to strike between ensuring the effectiveness of judgments and protecting third parties who acquire rights in good faith. It also illustrates the ongoing legal discussion regarding the precise procedural mechanisms and burdens of proof when extending judgment effects to successors with their own defenses.