Navigating Startup Investment in Japan: Key Legal Checkpoints for U.S. Investors

TL;DR

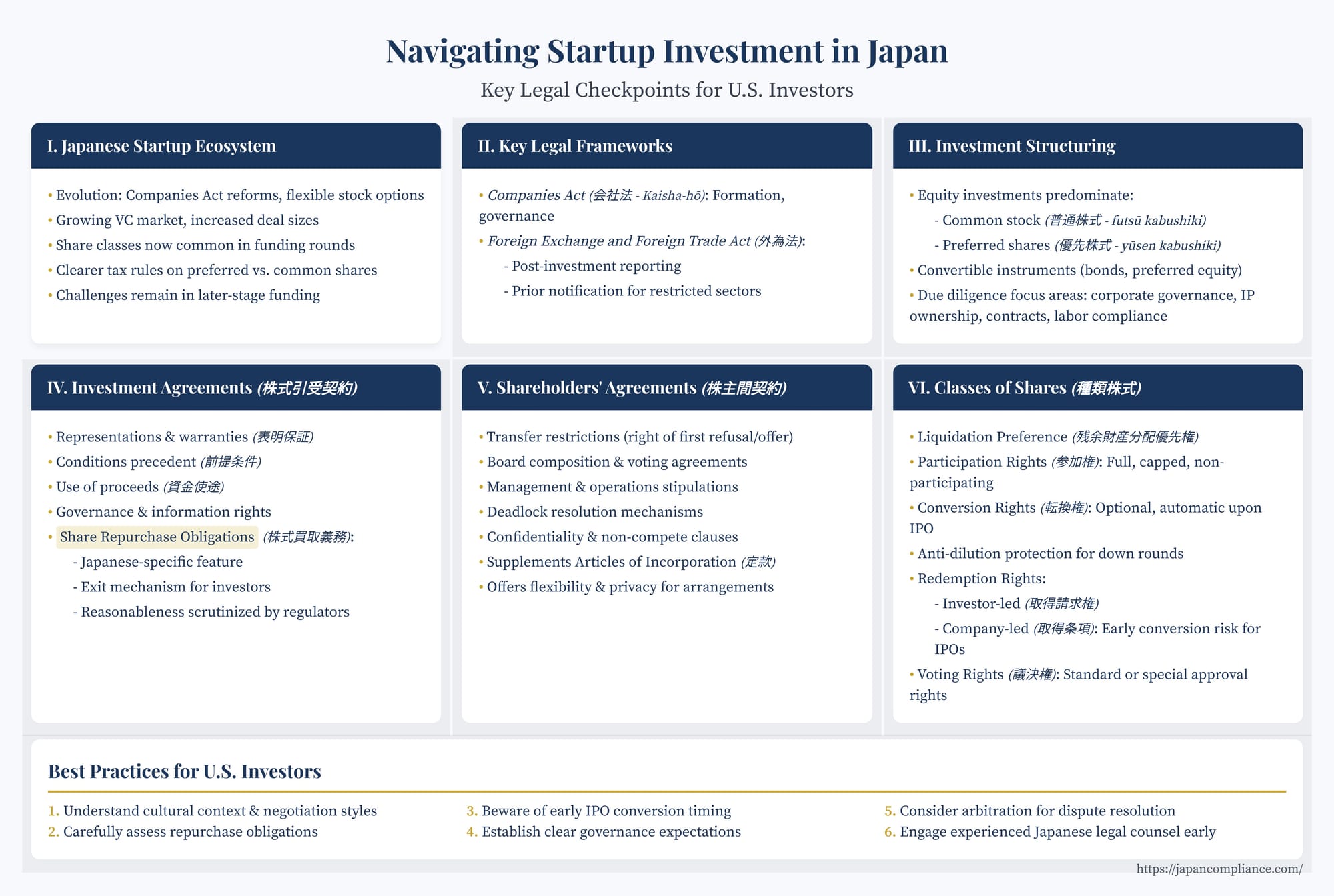

Japan’s startup ecosystem has matured rapidly, but successful U.S. investment still hinges on mastering Japanese legal frameworks—Companies Act, FEFTA compliance, share-class engineering, and culturally attuned deal terms such as share-repurchase obligations. This guide walks you through due diligence, preferred-share mechanics, governance rights, and common pitfalls so you can structure secure, growth-focused deals.

Table of Contents

- The Evolving Japanese Startup Scene: A Brief Overview

- Key Legal Frameworks

- Structuring the Investment

- Due Diligence: Beyond the Numbers

- Investment Agreements (Kabushiki Hikiuke Keiyaku)

5.1 Share Repurchase Obligations (Kabushiki Kaitori Gimu) - Shareholders' Agreements (Kabunushi-kan Keiyaku)

- The Strategic Use of Classes of Shares (Shurui Kabushiki)

- Potential Pitfalls and Best Practices for U.S. Investors

- Conclusion

Japan's startup ecosystem has undergone a remarkable transformation over the past two decades. Once perceived as lagging, it's now a dynamic landscape brimming with innovation and attracting increasing attention from international investors. For U.S. corporate legal professionals and business people eyeing opportunities in this market, understanding the nuances of Japanese startup investment is crucial. This article explores the key legal checkpoints, from structuring deals to navigating common contractual provisions.

The Evolving Japanese Startup Scene: A Brief Overview

The journey of Japan's startup environment has been one of significant legal and practical evolution. Revisions to the Companies Act, the introduction of flexible stock option schemes, and the diversification of M&A tools have collectively laid a more fertile ground for entrepreneurs and investors. Investment figures have seen a substantial rise, with both the total amount and the average deal size per company increasing. Venture capital, once dominated by financial institution-backed VCs, now sees a strong presence of independent VCs, partly thanks to legislative support for investment limited partnerships (LPS).

A notable trend is the increased use of different classes of shares in funding rounds, a practice that took time to gain traction but is now commonplace, utilized in a significant majority of startup financing. This adoption was also spurred by clarifications in tax rules regarding the valuation differences between common and preferred shares.

Despite these advancements, challenges remain, particularly in later-stage funding where the supply of capital and the number of startups ready for large-scale investment are still developing. This context shapes many of the legal practices and contractual terms encountered in Japanese startup investments.

Key Legal Frameworks

When investing in a Japanese startup, U.S. investors will primarily interact with the Companies Act (会社法 - Kaisha-hō), which governs the formation, operation, and governance of Japanese corporations (typically Kabushiki Kaisha, or K.K.). Additionally, the Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act (外国為替及び外国貿易法 - Gaikoku Kawase oyobi Gaikoku Bōeki-hō) may apply, requiring post-investment reporting or, in specific restricted sectors, prior notification for foreign investments.

Structuring the Investment

Equity investments are the norm for startups. While simple common stock (普通株式 - futsū kabushiki) investments occur, venture capital and later-stage investments almost invariably involve preferred shares (優先株式 - yūsen kabushiki). These are designed to offer investors downside protection and preferential economic rights. Convertible instruments, such as convertible bonds or convertible preferred equity, are also utilized, providing flexibility for both the investor and the startup.

Due Diligence: Beyond the Numbers

Thorough due diligence is paramount. Beyond the standard financial and business reviews, legal due diligence should focus on:

- Corporate Governance: Compliance with the Companies Act, internal controls, and decision-making processes.

- Intellectual Property: Ownership and protection of key IP assets.

- Contracts: Material agreements with customers, suppliers, and employees.

- Labor Law: Compliance with Japan's robust employee protection laws.

- Permits and Licenses: Necessary approvals for the startup's business operations.

A unique aspect to consider in Japan is the potential for unwritten understandings or practices that might not be immediately apparent from formal documentation. Cultural nuances in business relationships can also play a significant role.

Investment Agreements (株式引受契約 - Kabushiki Hikiuke Keiyaku)

The Investment Agreement is the cornerstone document outlining the terms of the investment. For U.S. investors, several clauses warrant close attention:

- Representations and Warranties (表明保証 - Hyōmei Hoshō): These are declarations by the startup and its founders about the state of the business. Breaches can lead to remedies for the investor. In Japan, the scope and detail of these clauses can vary, and it's crucial to ensure they provide adequate coverage.

- Conditions Precedent (前提条件 - Zentei Jōken): These are conditions that must be met before the investor is obligated to close the investment.

- Use of Proceeds (資金使途 - Shikin Shito): Restrictions or guidelines on how the invested capital will be used. Misuse of funds can be a trigger for investor remedies.

- Governance and Information Rights: These may include rights to appoint a director or observer to the board, and rights to receive regular financial and operational reports.

- Investor Protective Provisions (Veto Rights): Certain corporate actions may require investor consent (事前承認権 - jizen shōninken). These often cover major decisions like issuing new shares, amending the articles of incorporation, selling significant assets, or changing the nature of the business. The enforceability and practicality of these rights are key.

- Exit Clauses: Provisions related to IPOs (e.g., cooperation from the company and founders), drag-along rights (where majority shareholders can force minority shareholders to join a sale of the company), and tag-along rights (allowing minority shareholders to join a sale initiated by majority shareholders).

A Unique Feature: Share Repurchase Obligations (株式買取義務 - Kabushiki Kaitori Gimu)

A distinctive feature often found in Japanese startup investment agreements is the share repurchase obligation imposed on the company or its founding shareholders. This clause typically allows investors to demand that their shares be bought back under certain circumstances, such as:

- Breach of material representations and warranties.

- Misuse of investment funds by the company or founders.

- Failure to obtain investor's prior approval for critical corporate actions.

- Failure to achieve an IPO by a certain date (though this is increasingly scrutinized).

The rationale behind these clauses, historically, was to provide investors with an exit mechanism and a remedy in a market where IPOs were the primary exit route and minority shareholder protections might have been perceived as less robust.

However, the fairness and enforceability of these provisions, particularly when they impose a heavy burden on founders or the company itself, have been subjects of debate and scrutiny. Japanese regulatory bodies have issued guidelines suggesting that such clauses should be reasonable and not unduly disadvantageous to the startup or its founders. For instance, setting an excessively high repurchase price or triggering repurchase for minor breaches could be problematic.

When negotiating these clauses, U.S. investors should consider:

- Triggers: Are they clearly defined and linked to material issues?

- Valuation: How is the repurchase price determined? Common methods include the original investment amount plus interest, fair market value, or a pre-agreed formula. The method should be commercially reasonable.

- Obligor: Is the obligation on the company, the founders, or both? Repurchase by the company is subject to Japanese company law restrictions on share buybacks (e.g., distributable profits). Founder obligations can create significant personal financial risk.

- Reasonableness: The overall impact of the clause on the startup's ability to operate and grow.

While providing a level of security, overly aggressive repurchase clauses can stifle a startup's growth or even lead to disputes. A balanced approach that protects legitimate investor interests without crippling the company is essential.

Shareholders' Agreements (株主間契約 - Kabunushi-kan Keiyaku)

Alongside the Investment Agreement, a Shareholders' Agreement is often executed. This agreement governs the ongoing relationship among shareholders, including founders and multiple investors who may enter at different funding rounds.

Key areas covered typically include:

- Transfer of Shares: Restrictions on share transfers (e.g., right of first refusal, right of first offer).

- Board Composition and Voting: Agreements on director nomination rights and voting for specific matters. Recent Japanese court decisions have affirmed the enforceability of voting agreements, providing greater certainty.

- Management and Operations: Sometimes, key management roles or operational undertakings are outlined.

- Deadlock Resolution: Mechanisms to resolve disputes among shareholders.

- Confidentiality and Non-Compete Clauses.

Shareholders' Agreements supplement the company's Articles of Incorporation (定款 - Teikan). While some governance matters can be enshrined in the Articles, shareholder agreements offer more flexibility and privacy for bespoke arrangements among specific parties. However, it's crucial to ensure consistency between the Shareholders' Agreement and the Articles of Incorporation to avoid conflicts.

The Strategic Use of Classes of Shares (種類株式 - Shurui Kabushiki)

As mentioned, the use of different classes of shares is a cornerstone of modern Japanese startup finance. U.S. investors will typically receive preferred shares with rights superior to common shares held by founders and employees.

Common features of preferred shares in Japan include:

- Liquidation Preference (残余財産分配優先権 - Zanyo Zaisan Bunpai Yūsenken): In the event of a liquidation, merger, or sale of the company (often covered by "deemed liquidation clauses" or みなし清算条項 - minashi seisan jōkō), preferred shareholders receive their investment back (often with a multiple or accrued dividends) before common shareholders receive any proceeds.

- Participation Rights (参加権 - Sankaken): After receiving their liquidation preference, preferred shareholders may also "participate" with common shareholders in the distribution of remaining assets, either on an as-converted basis (fully participating) or up to a certain cap (capped participation). Non-participating preferred shares are also common, particularly in later rounds or if the preference multiple is high.

- Conversion Rights (転換権 - Tenkanken): Preferred shares are typically convertible into common shares, often at the option of the holder and automatically upon a qualified IPO. Anti-dilution provisions adjust the conversion price to protect investors from dilution if the company issues new shares at a lower price than the preferred shareholders paid ("down rounds").

- Redemption Rights (取得請求権/取得条項 - Shutoku Seikyūken/Shutoku Jōkō):

- Investor-led Redemption (取得請求権 - Shutoku Seikyūken): Gives the investor the right to require the company to redeem their shares after a certain period if an exit event (like an IPO or M&A) has not occurred. This is akin to a repurchase obligation.

- Company-led Redemption (取得条項 - Shutoku Jōkō): Allows the company to force conversion or redeem shares, often used to simplify the capital structure before an IPO. In Japan, it's common practice for preferred shares to be converted to common stock before an IPO application is formally approved by the exchange, a timing that can pose risks if the IPO is delayed or aborted post-conversion.

- Voting Rights (議決権 - Giketsuken): Preferred shares may have standard voting rights on an as-converted basis, or they may have special approval/veto rights over certain corporate actions, as mentioned under Investor Protective Provisions. While the Companies Act allows for appointing directors through class-specific voting (クラスボーティング - kurasu bōtingu), this is not as commonly used for board representation in practice compared to contractual rights in shareholders' agreements. This is sometimes due to concerns about the public registration (登記 - tōki) of such detailed class rights and a preference for the flexibility of contractual arrangements.

The specific terms of preferred shares are heavily negotiated and reflect the stage of the startup, the amount of investment, the relative bargaining power of the parties, and market conditions.

Potential Pitfalls and Best Practices for U.S. Investors

- Understanding Cultural Context: Japanese negotiation styles can be less direct. Building relationships and understanding implicit communications are vital.

- Repurchase Obligations: Carefully assess the triggers, valuation, and impact of these clauses. Seek a balance that protects your investment without unduly burdening the startup.

- IPO Conversion Timing: Be aware of the practice of early conversion of preferred shares before an IPO is fully secured and negotiate protections if possible.

- Governance Expectations: While founder control is common in early stages, establishing clear governance rights and expectations early on is crucial, especially as the company scales.

- Enforcement: While the legal framework is robust, enforcement of contractual rights through litigation can be time-consuming. Consider dispute resolution mechanisms like arbitration.

- Local Legal Counsel: Engage experienced Japanese legal counsel early in the process. They can navigate local laws, regulations, and market practices effectively.

Conclusion

Investing in Japanese startups offers exciting potential for U.S. companies and investors. The legal landscape, while having its unique features, has matured significantly to support venture investment. By understanding key contractual provisions like share repurchase obligations, the strategic use of different classes of shares, and the nuances of shareholders' agreements, U.S. investors can better navigate this dynamic market, structure sound investments, and protect their interests while fostering innovation and growth in Japan.