Navigating Senior Leases and Junior Mortgages: A Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Eviction Orders

Case Name: Appeal Against a Higher Court's Decision Annulling the Original Decision on an Appeal Against a Real Property Eviction Order

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Case Number: Heisei 12 (Kyo) No. 22

Date of Decision: January 25, 2001

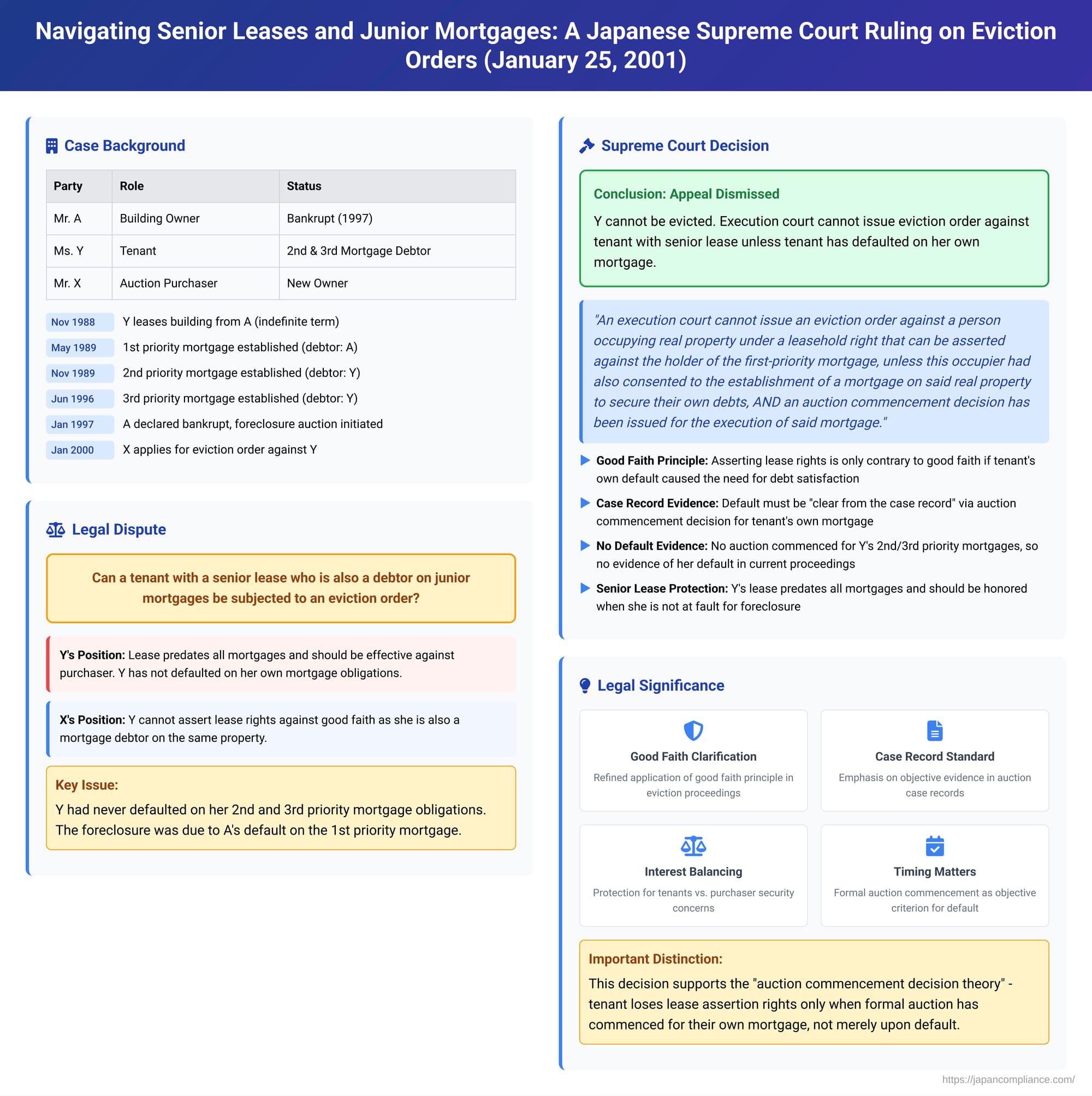

This article examines a significant decision by the Japanese Supreme Court dated January 25, 2001. The case delves into the complex interplay between a tenant's rights under a lease that predates a senior foreclosed mortgage and the tenant's obligations as a debtor under a separate, junior mortgage on the same property. Specifically, it addresses whether such a tenant can be subjected to an eviction order (hikiwatashi meirei) following an auction if they are not in default on their own mortgage debt.

Factual Chronology: A Web of Rights and Obligations

The facts leading to this Supreme Court decision are as follows:

- Ownership and Lease: Mr. A was the owner of a building ("the Building").

- November 1, 1988: Ms. Y (the respondent in the Supreme Court, original appellant, and tenant) leased the Building from Mr. A for an indefinite term and commenced occupation. Crucially, this lease was established before any mortgages were placed on the Building.

- Mortgages:

- May 1, 1989: A first-priority base mortgage (neteitōken) was established on the Building, with Mr. A as the debtor.

- November 18, 1989: A second-priority base mortgage was established, with Ms. Y (the tenant) as the debtor.

- June 5, 1996: A third-priority base mortgage was established, also with Ms. Y as the debtor.

All mortgages were duly registered.

- Owner's Bankruptcy and Auction Initiation:

- January 13, 1997: Mr. A, the owner, was declared bankrupt.

- March 18, 1997: The first-priority mortgagee initiated a foreclosure auction (担保不動産競売 - tanpo fudōsan keibai) against the Building due to Mr. A's default.

- Auction Proceedings: The Building was subsequently abandoned from Mr. A's bankruptcy estate by the bankruptcy trustee, and the foreclosure auction initiated by the first-priority mortgagee proceeded.

- Purchase and Eviction Application: Mr. X (the petitioner in the Supreme Court, original respondent, and auction purchaser) became the successful bidder and new owner of the Building. After paying the purchase price, Mr. X, on January 26, 2000, applied to the execution court for an eviction order against Ms. Y, who was still occupying the Building.

- Tenant's Mortgage Status: A key fact is that Ms. Y had never defaulted on her own obligations secured by the second and third-priority base mortgages.

The Legal Conundrum: Can the Tenant's Senior Lease Prevail?

The central issue was whether Ms. Y, despite being a debtor under junior mortgages, could assert her leasehold rights—which predated all mortgages—against Mr. X, the auction purchaser. Generally, a lease that is senior to a foreclosed mortgage can be asserted against the purchaser. However, Ms. Y's status as a debtor for other mortgages on the same property complicated the matter.

Path Through the Lower Courts

- Execution Court (Yokohama District Court, Kawasaki Branch): The execution court granted Mr. X's application and issued an eviction order against Ms. Y.

- High Court (Tokyo High Court): Ms. Y appealed this order. The Tokyo High Court reversed the execution court's decision, finding that Ms. Y's appeal was meritorious and dismissed Mr. X's application for an eviction order. The High Court reasoned as follows:

- If a tenant, whose lease is otherwise valid against third parties, is also the debtor for a mortgage on the leased property, and that mortgage is foreclosed due to the tenant's own default, the tenant generally cannot assert their lease against the auction purchaser. This is because it would be contrary to good faith and equity for the tenant to cause the foreclosure through their default and then benefit from the lease to the detriment of the sale.

- However, this principle does not apply if the tenant-debtor is not in default on their own mortgage obligations. In such a scenario, the foreclosure is not due to their fault. If the auction is triggered by the default of another party (like the owner under a senior mortgage), and the tenant's own mortgage is simply extinguished due to the "elimination principle" (shōjo shugi, where junior encumbrances are wiped out by the auction), there is no basis to strip the tenant of their otherwise valid senior lease rights.

- In Ms. Y's case, she had not defaulted on her mortgage debts. The auction was due to Mr. A's default on the first mortgage. Therefore, Ms. Y could assert her lease against Mr. X.

Mr. X then sought and was granted permission to appeal to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision

On January 25, 2001, the Supreme Court (Third Petty Bench) dismissed Mr. X's appeal, thereby upholding the High Court's decision that Ms. Y could not be evicted under these circumstances.

The Supreme Court's key holding was:

"An execution court cannot issue an eviction order against a person occupying real property under a leasehold right that can be asserted against the holder of the first-priority mortgage, unless this occupier had also consented to the establishment of a mortgage on said real property to secure their own debts, AND an auction commencement decision (including a concurrent auction commencement decision) has been issued for the execution of said mortgage."

The Court elaborated on its reasoning:

- The Principle of Good Faith (Shingi-soku): Even if a person occupies property under a lease that is senior to the first-priority mortgage, if that property was also pledged as security for the occupier's own debts, and circumstances arise where those debts should be satisfied from the sale proceeds of that mortgaged property due to the occupier's default, then asserting the leasehold right would be contrary to the principle of good faith. This is because asserting the lease could hinder the sale of the mortgaged property or cause a reduction in its sale price, thereby harming the interests of both the mortgagee (whose loan is secured by the tenant's mortgage) and the owner who provided the property as security. In such cases, the occupier cannot assert their lease against the auction purchaser.

- Evidence of Default in the "Case Record": When an auction commencement decision has been issued for the execution of the mortgage securing the occupier's own debts, the fact of their default is considered "clear from the case record" as stipulated in the proviso to Article 83, Paragraph 1 of the Civil Execution Act (Minji Shikkō Hō). In such a situation, asserting the lease is impermissible within the execution proceedings.

- Absence of Default in the Record: However, if no auction commencement decision has been issued for the execution of the mortgage securing the occupier's own debts, then the fact of their default is not clear from the execution case record of the current auction (which is proceeding based on the foreclosure of a different, typically senior, mortgage). In this situation, the occupancy is considered to be based on a leasehold right that can be asserted against the purchaser.

Applying this to the present case, the Supreme Court noted that, according to the execution case record:

- Ms. Y occupied the Building under a leasehold right that was senior to (and thus effective against) the first-priority mortgage being foreclosed.

- Although Ms. Y had consented to the establishment of mortgages on the Building to secure her own debts (the second and third-priority mortgages), no auction commencement decision had been issued based on these mortgages.

Therefore, the conditions for issuing an eviction order against Ms. Y were not met. The High Court's decision to dismiss Mr. X's application for an eviction order was affirmed.

Analysis and Significance

This Supreme Court decision offers crucial guidance on the rights of tenants in foreclosure sales, particularly when those tenants also have their own mortgage obligations related to the property.

- Clarification of the Good Faith Principle: The ruling refines the application of the good faith principle (shingi-soku) in eviction order proceedings. It confirms that a tenant acting against good faith by asserting a senior lease typically involves a situation where their own default on a mortgage they granted is the reason their secured debt should be paid from the property's sale.

- Importance of the "Case Record": The decision underscores the significance of what is objectively ascertainable from the "case record" (jiken no kiroku jō) of the specific auction proceeding, as per Article 83(1) of the Civil Execution Act. An eviction order is a summary proceeding, and the court relies on information readily available in the record. If the tenant's default on their own mortgage isn't evidenced by an auction commencement decision for that mortgage within the current proceedings' records, their senior lease rights are likely to be upheld against the purchaser.

- "Auction Commencement Decision Theory" Favored: The commentary surrounding this case indicates that the Supreme Court's reasoning aligns with what is known as the "auction commencement decision theory" (kaishi kettei ji kōtei setsu). This theory posits that a tenant-debtor under a non-executing mortgage (a mortgage not currently being foreclosed) loses the right to assert their senior lease only if an auction has formally commenced due to their default on that specific mortgage. This contrasts with the "default time theory" (saimu furikō ji kōtei setsu), which might argue that merely being in a state of default on their mortgage, even if not yet formally acted upon by foreclosure, could be sufficient to prevent them from asserting their lease on good faith grounds. The Supreme Court's focus on the formal auction commencement decision as the trigger provides a clearer, more objective criterion.

- Balancing Interests: The decision attempts to strike a balance. It protects auction purchasers from tenants who, through their own default on related mortgages, might unfairly impede the sale or diminish the property's value. However, it also protects tenants with valid senior leases if their own mortgage obligations are not the cause of the current foreclosure and their default is not formally established in the ongoing proceedings.

- Interaction with Subsequent Legal Reforms:

- 2003 Security/Execution Law Reforms: These reforms introduced a system of eviction grace periods for buildings (e.g., former Civil Code Article 395, allowing a six-month grace period for occupants under certain conditions after an auction). The commentary suggests that even if a tenant-debtor (under a non-executing mortgage) is merely in default but no auction has commenced for their mortgage, making an eviction order difficult under the logic of the present Supreme Court decision, it might still be possible to seek eviction through ordinary civil litigation during any such grace period if their continued occupancy is deemed inequitable. The direct application of the grace period to a tenant who is deemed to be acting against good faith (e.g., a defaulting debtor on the executing mortgage) is likely to be denied.

- 2018 Inheritance Law Reforms: These reforms introduced spousal residential rights (e.g., Civil Code Article 1028). The commentary raises the question of whether this Supreme Court decision's logic would apply if a spouse holding such a registered residential right was also the debtor under the foreclosed mortgage. If spousal residential rights are seen as analogous to leasehold rights, then asserting them might be denied if it contravenes good faith by harming the sale due to the spouse's own default.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's January 25, 2001, decision provides critical clarity for a nuanced scenario in Japanese real estate foreclosure law. It establishes that a tenant with a lease predating a foreclosed senior mortgage, who is also a debtor under a junior mortgage on the same property, cannot be evicted via an eviction order unless an auction has formally commenced due to the tenant's default on their own mortgage. This ruling emphasizes the importance of objectively verifiable facts within the auction case record and carefully applies the principle of good faith, ensuring that tenants are not unjustly deprived of senior leasehold rights when they are not responsible for the specific foreclosure event.