Navigating Regulatory Compliance and Public Works: A Japanese Supreme Court Precedent

Date of Judgment: February 18, 1983

Case: Loss Compensation Ruling Revocation Request Case

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

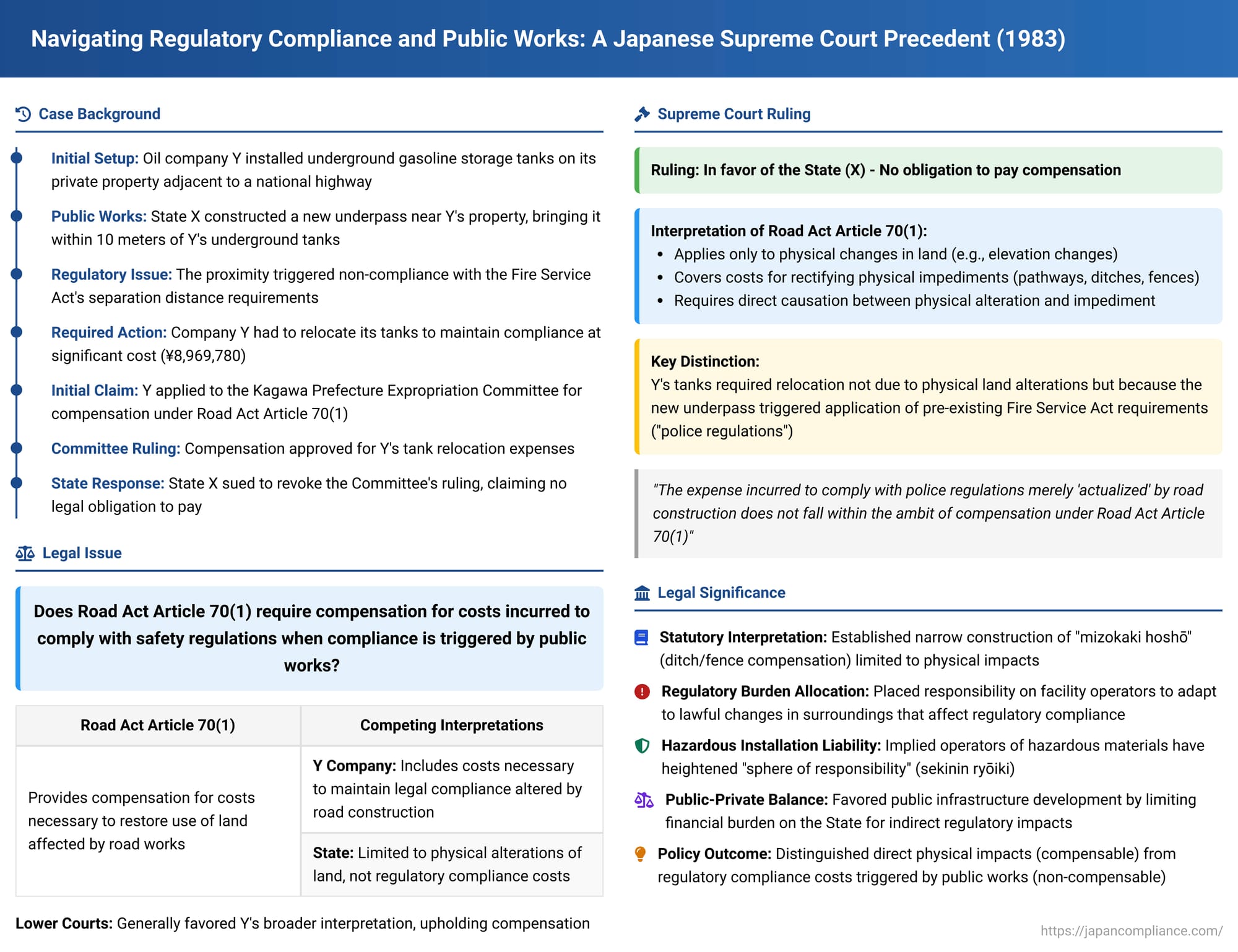

Businesses operating in developed nations often encounter situations where public infrastructure projects interact with their existing operations. A crucial question that can arise is who bears the financial burden when such projects necessitate changes to private property, not due to direct physical damage or expropriation, but because the new public work renders an existing facility non-compliant with safety or other regulations. A landmark decision by the Supreme Court of Japan on February 18, 1983, delved into this complex interplay, offering significant insights into the interpretation of statutory compensation provisions and the allocation of responsibility when regulatory compliance costs are triggered by public works. This case, involving the relocation of underground fuel storage tanks, provides a detailed examination of the boundaries of state compensation obligations.

The Factual Matrix: A Collision of Public Works and Private Enterprise

The case involved Y Company, an oil corporation, which had lawfully installed underground gasoline storage tanks on its privately-owned land. This land was situated adjacent to a national highway. The company operated a petroleum service station at this location, and the tanks were an essential part of its business infrastructure.

Sometime after the installation and compliant operation of these tanks, X (the State), acting as the road administrator, undertook a significant public works project: the construction of a new underpass in the vicinity of Y Company's property. The completion of this underpass brought its structure within a 10-meter horizontal distance of Y Company's underground tanks.

This proximity created a new legal issue. The Japanese Fire Service Act, a comprehensive piece of legislation aimed at preventing and mitigating fire hazards, along with its related cabinet orders and ministerial ordinances, stipulated specific technical standards for facilities handling dangerous materials like gasoline. Among these were "separation distance" requirements, mandating a minimum distance between hazardous material storage and certain public structures, including underpasses, to ensure public safety. With the new underpass now closer than the prescribed 10 meters, Y Company's tanks, though previously compliant, were thrust into a state of "police violation" – meaning they no longer met the existing safety regulations due to the changed external circumstances created by the State's actions.

To rectify this regulatory non-compliance and continue its operations lawfully, Y Company was compelled to undertake the costly process of relocating its underground storage tanks to a different position on its property that would satisfy the Fire Service Act's distance requirements from the new underpass. Faced with these substantial, unanticipated expenses, Y Company sought financial redress. It applied to the Kagawa Prefecture Expropriation Committee, arguing for compensation for the relocation costs. The legal basis for its claim was Article 70, Paragraph 1 of Japan's Road Act.

The Legal Path: From Local Committee to the Supreme Court

The Kagawa Prefecture Expropriation Committee, the body responsible for adjudicating such compensation claims related to land use and public works, reviewed Y Company's application. The Committee found merit in Y Company's position and issued a ruling that approved the company's claim for compensation, ordering the State to pay for the tank relocation expenses, which amounted to 8,969,780 yen.

Dissatisfied with this outcome, X (the State) initiated legal proceedings. The State filed a lawsuit seeking two primary remedies: first, the revocation of the Expropriation Committee's ruling that had granted compensation to Y Company, and second, a declaratory judgment confirming that the State had no legal obligation to pay the said compensation amount to Y Company for the relocation of the tanks.

The case then proceeded through the lower courts. Both the court of first instance and the subsequent appellate court (the second instance court) largely sided with Y Company, upholding, in principle, its right to compensation. These lower courts were inclined to interpret the relevant compensation provisions in a manner that accommodated Y Company's loss, seemingly influenced by the fact that the State's actions had directly led to the company incurring significant expenses. However, the State remained steadfast in its position that it was not liable for these particular costs under the cited law, leading to a final appeal to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision of February 18, 1983

The Supreme Court, in its judgment delivered by the Second Petty Bench, took a decidedly different stance from the lower courts. The Court overturned the prior decisions that had favored Y Company and ultimately ruled in favor of X (the State). The core of the Supreme Court's decision rested on its meticulous interpretation of Article 70, Paragraph 1 of the Road Act, the specific statutory provision upon which Y Company had based its claim.

The Court began by elucidating its understanding of the purpose and scope of this article. It stated that Article 70, Paragraph 1 of the Road Act is designed to address situations where the construction or alteration of a road by the road administrator leads to physical changes in the land, such as the creation of a height difference between the road and the adjacent private property. When these physical changes directly cause an impediment to the use or management of the adjacent land, preventing its owner from continuing to use or manage it as before, Article 70(1) comes into play.

According to the Supreme Court, the compensation envisioned by this provision is specifically for expenses unavoidably incurred to rectify such physical impediments. This includes costs for works like constructing, improving, repairing, or relocating ancillary structures such as pathways, ditches, fences, or similar installations. It also covers expenses for necessary earthworks, like cutting or banking soil, to restore the utility or manageability of the land disrupted by the road project's physical impact. Crucially, the Court emphasized that the compensable loss must be a direct consequence of the physical alteration of the land's topography or shape caused by the road construction.

Applying this interpretation to the facts of Y Company's case, the Supreme Court found a fundamental disconnect. Y Company had relocated its tanks not because the new underpass had physically altered its land in such a way as to make the tanks' original location unusable (e.g., by creating an unstable slope or a direct physical obstruction to access). Instead, the relocation was necessitated because the presence of the underpass, in its newly constructed location, triggered a pre-existing regulatory requirement under the Fire Service Act. The construction of the underpass resulted in a "police violation" – a failure to meet the technical safety standards concerning separation distances for hazardous materials.

The Supreme Court characterized this loss as one where a police regulation (the Fire Service Act's standards) was merely "actualized" or brought into effect by the road construction. The expense incurred by Y Company was to bring its facility into compliance with these police regulations. Such a loss, the Court concluded, does not fall within the ambit of compensation provided for under Article 70, Paragraph 1 of the Road Act. That provision, the Court reiterated, is concerned with restoring the usability of land affected by direct physical changes from road works, not with covering costs associated with meeting collateral regulatory standards, even if those standards are triggered by the road works.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the lower court's judgment, which had found Y Company's losses to be compensable under Road Act Article 70(1), was based on an erroneous interpretation and application of the law. This error, being critical to the outcome, justified the reversal of the lower court's decision. The Supreme Court then proceeded to directly rule on the merits, revoking the Expropriation Committee's compensation award to Y Company and confirming that the State had no obligation to pay the claimed amount.

Deconstructing the Rationale: A Deep Dive into Legal Interpretations

The Supreme Court's decision was not merely a technical application of a statute but reflected deeper considerations about the nature of regulatory burdens, causation, and the responsibilities of entities handling potentially hazardous materials.

The Textual Boundaries of Road Act Article 70(1): "Mizokaki Hoshō"

Article 70, Paragraph 1 of the Road Act is sometimes colloquially referred to as "mizokaki hoshō," which translates to "ditch/fence compensation." This moniker itself hints at the types of direct, physical alterations and consequent remedial works the provision traditionally targets. The article specifically lists examples such as "passages, ditches, fences, or similar structures" and "cutting or banking of soil." The Supreme Court's interpretation adhered closely to this textual emphasis on physical changes and the direct consequences thereof.

Legal commentators have generally agreed that the Supreme Court's narrow construction of this article is textually sound. The requirements for compensation under this provision typically involve:

- The new construction or reconstruction of a road.

- An impact on land that directly adjoins the road.

- A resultant, unavoidable necessity to undertake work such as new construction, extension, repair, or relocation of specific types of ancillary structures (like passages or fences), or to perform earthworks.

- This necessity must arise from an impediment to the use or management of the land, directly caused by physical changes to the land's condition (e.g., altered elevation, severed access) due to the road project.

Y Company's situation did not neatly fit these criteria. The underpass construction did not, for instance, create a sudden cliff on Y Company's land or block access in a way that required a new retaining wall or pathway merely to continue using the land as before. The impediment was regulatory, not directly physical in the sense described by the statute. The lower courts had adopted a more expansive view, suggesting that Article 70(1) could encompass losses stemming from legal or regulatory constraints triggered by roadworks, even if the examples given in the statute were primarily physical. The Supreme Court rejected this broader interpretation as being inconsistent with the plain language and established purpose of the provision.

The Nature of the Loss: Physical Impediment vs. Regulatory Compliance

A pivotal distinction drawn by the Supreme Court was between losses stemming from direct physical interference with land use and losses incurred to comply with what it termed "police regulations." The Fire Service Act, with its safety distance requirements, falls into the category of police regulations – laws designed to maintain public safety and order by imposing standards on certain activities or facilities.

The Court's view was that the road construction did not, in itself, physically prevent Y Company from using the land where the tanks were located. Rather, the road construction created a new external condition (the proximity of the underpass) that brought Y Company's pre-existing facility into conflict with the existing Fire Service Act standards. The financial loss was the cost of resolving this regulatory conflict. This, in the Court's eyes, was fundamentally different from compensating a landowner for, say, having to build a new access ramp because a road project changed the street level, making their driveway unusable.

The Role of "Police Regulations" (Fire Service Act)

The judgment implied that the duty to comply with such police regulations primarily rests with the entity whose activities or facilities are subject to those regulations – in this case, Y Company, as the operator of a gasoline storage facility. The road construction was the event that triggered the non-compliance, but the underlying obligation to meet the Fire Service Act's safety standards was always incumbent upon Y Company.

This line of reasoning suggests that when public works lead to a state of regulatory violation for an adjacent property, the costs of rectifying that violation are not automatically the responsibility of the public entity undertaking the works, at least not under a statute like Road Act Article 70(1). The direct legal source of the obligation to move the tanks was the Fire Service Act, not the Road Act. If compensation were to be due for costs incurred purely due to the Fire Service Act, that Act itself would typically be expected to contain provisions for such compensation. However, the Fire Service Act, in this type of scenario, did not provide for compensation to businesses required to modify their facilities to meet its standards due to nearby public developments.

Causation and Responsibility: Who Bore the Onus?

The question of causation is central. Did the State's underpass construction "cause" Y Company's loss? In a "but-for" sense, yes: but for the underpass, the tanks would not have needed to be moved. However, the Supreme Court's reasoning points to a more nuanced view of legal causation and responsibility.

The Court seemed to adopt a perspective that the responsibility for ensuring that a hazardous facility (like a gasoline storage tank) remains compliant with safety regulations lies with the owner or operator of that facility. The State's action (building the underpass) was a lawful exercise of its public duties. While this action created a new circumstance, the legal imperative to move the tanks arose from the Fire Service Act's pre-existing and overarching safety requirements. The loss was, in this view, a "police regulation-based loss" that happened to be actualized by the road project.

This resonates with legal concepts sometimes discussed in administrative law, such as "Zustandshaftung" (often translated as "condition responsibility" or "state responsibility," though the latter can be confusing in English; it refers to liability arising from the condition of property). The idea is that the owner of property that poses a potential risk or is subject to specific safety regulations bears a certain inherent responsibility for maintaining that property in a compliant and safe state, even if external factors change.

Foreseeability and the "Sphere of Responsibility" for Hazardous Installations

Perhaps the most profound aspect of the underlying legal thinking, as also explored in legal commentaries on this case, touches upon foreseeability and the allocation of risk. When Y Company initially installed its gasoline tanks, it did so under a regulatory regime (the Fire Service Act) that already stipulated separation distances from certain types of structures, including underpasses. Even if no underpass existed nearby at the time of installation, the possibility of future, lawful public development in the vicinity was arguably a latent risk.

The argument supporting the Supreme Court's conclusion is that a business operating a facility with inherent hazards, subject to specific safety regulations like distance requirements, has a degree of responsibility to anticipate potential future lawful developments on adjacent land. Had Y Company, for instance, initially sited its tanks further away from the boundary of the public highway, it might have avoided the subsequent conflict when the underpass was built. To suggest that public infrastructure projects must either be routed around all existing private facilities (that might become non-compliant) or automatically trigger compensation if they are not, could significantly hinder public development.

This perspective places the onus on the "kiken jakkisha" (the party creating the risk – here, Y Company, by storing hazardous materials) to manage its operations within a "sekinin ryōiki" (sphere of responsibility) that includes considering the dynamic nature of the surrounding environment, particularly concerning lawful public works. This does not mean that the business is at fault, but rather that the risk of having to adapt to new, lawful neighboring developments (in terms of regulatory compliance) may, to some extent, lie with the business.

Exceptions might be considered if, for example, the State had expropriated Y Company's land to build the underpass (which would trigger compensation under land expropriation laws) or if the underpass had been constructed illegally or in an area where such structures were prohibited. However, those were not the facts of this case. The underpass was a lawful public work.

The lower courts had leaned towards the view that Y Company could not easily have foreseen the future state of non-compliance and that the relocation was forced upon it by circumstances beyond its control. However, the Supreme Court's implicit stance is more stringent: operators of facilities subject to strict safety regulations tied to proximity must factor in the potential for lawful changes in their surroundings.

Broader Implications: Balancing Public Development and Private Interests

This case illustrates the delicate balance that legal systems must strike between facilitating necessary public infrastructure development and protecting the economic interests of private entities. If any indirect cost incurred by a private party due to public works automatically qualified for compensation, the financial burden on the state could become prohibitive, potentially stalling essential projects. Conversely, leaving private parties to bear all costs associated with adapting to changes brought about by public projects, even regulatory compliance costs, can seem unfair, especially when the original installation was perfectly lawful.

The Supreme Court's decision in this case drew a relatively firm line, confining compensation under Road Act Article 70(1) to direct physical impacts. It implicitly suggested that costs arising from the need to comply with general safety regulations, even when triggered by public works, are part_._of the broader regulatory landscape in which businesses operate.

Constitutional Undercurrents

While not explicitly a constitutional case centered on "takings" or just compensation under constitutional property rights clauses, the backdrop of such principles is often present in compensation disputes. The lower courts' willingness to grant compensation might have been influenced by a general sense that it was constitutionally "just" for Y Company to be compensated since the State's project led to its expense.

However, the Supreme Court's decision, by narrowly interpreting the specific statute and emphasizing the nature of the loss as a "police regulation-based loss," suggests that not every economic detriment caused by government action rises to the level of a constitutionally compensable taking, especially when the cost is incurred to comply with pre-existing public safety laws. The financial burden was seen as an outcome of Y Company's obligation to adhere to the Fire Service Act in light of new, lawful circumstances created by the State, rather than a direct appropriation or physical damaging of property by the State for public use that would more clearly demand compensation under general constitutional principles.

Conclusion

The February 18, 1983, Supreme Court decision in the Loss Compensation Ruling Revocation Request Case provides a critical precedent in Japanese administrative law concerning compensation for losses incurred by private entities due to public works. The Court established a clear distinction between compensation for direct physical impediments to land use caused by road construction (covered by Road Act Article 70, Paragraph 1) and costs incurred to comply with separate "police regulations" (such as the Fire Service Act), even when such compliance is necessitated by the public works.

The judgment underscores that the mere fact that a lawful public project triggers a regulatory non-compliance for an adjacent private facility does not automatically render the state liable for the costs of achieving compliance, at least not under statutes primarily aimed at redressing direct physical impacts. Instead, the ruling implies that businesses, particularly those handling hazardous materials subject to stringent safety codes, operate within a dynamic legal and physical environment and bear a degree of responsibility for anticipating and adapting to lawful changes in their surroundings, including the emergence of new public infrastructure that might affect their regulatory obligations. This case serves as a key reference for understanding the allocation of financial burdens at the intersection of public development and private enterprise under Japanese law.