Navigating Procedural Boundaries: Japanese Supreme Court on Joining Loss Compensation Claims to State Compensation Lawsuits

Date of Judgment: July 20, 1993

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

Introduction

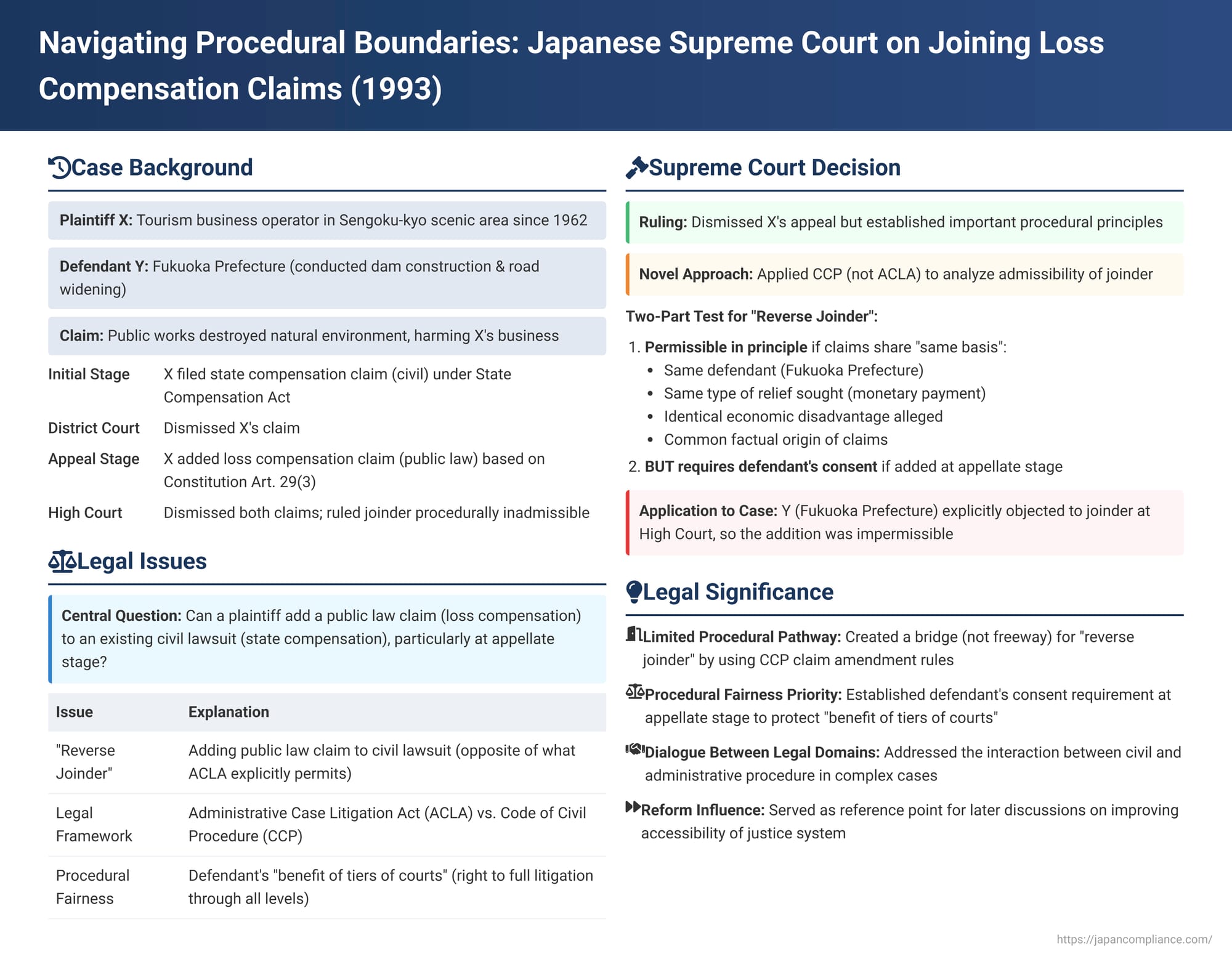

On July 20, 1993, the Third Petty Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a nuanced judgment in a case often referred to by the plaintiff's name, X, against Fukuoka Prefecture. The central issue was a matter of civil procedure with significant implications for how claims against the state are litigated: the permissibility of a plaintiff adding a "loss compensation" claim, which is considered a public law matter, to an existing "state compensation" lawsuit, a civil law matter, particularly when this addition is attempted at the appellate stage. This scenario is sometimes termed "reverse joinder." The Supreme Court's decision shed light on the conditions under which such joinders might be allowed, focusing on the Code of Civil Procedure rather than the Administrative Case Litigation Act, and underscored the paramount importance of procedural fairness, notably the defendant's consent at the appeal level.

I. Factual Background: Business Disruption and a Quest for Redress

The case arose from disruptions experienced by a private business operator due to public works projects.

The Plaintiff's Business

The plaintiff, X, had been operating a ryokan (a traditional Japanese inn) and other tourism-related businesses since approximately 1962. These operations were located in a scenic area known as "Sengoku-kyo," situated within the Dazaifu Prefectural Natural Park in Fukuoka Prefecture.

The State's Actions

The defendant, Y (Fukuoka Prefecture), undertook significant public works projects in the vicinity of X's business operations. These projects involved the construction of a dam and the associated widening of roads.

The Alleged Harm

X contended that these extensive public works carried out by the prefecture resulted in the destruction of the surrounding natural environment, which was crucial for the appeal of X's tourism-focused business. Consequently, X claimed to have suffered a substantial decline in business activities and profitability.

Initial Lawsuit

In response to these alleged losses, X initially filed a lawsuit against Fukuoka Prefecture seeking monetary damages. This primary claim was based on Article 1 of the State Compensation Act, which governs the state's liability for damages caused by the unlawful exercise of public power by public officials. As an alternative legal basis, X also cited Article 415 of the Civil Code, which deals with default on contractual obligations (though its direct applicability to a non-contractual claim against the state for public works impacts is less clear and was likely presented as a fallback argument).

II. Procedural Journey and the Attempted Joinder

The litigation took a complex turn as it moved through the court system, particularly concerning the addition of a new type of claim.

District Court Decision

The court of first instance, the Fukuoka District Court (Nogata Branch), heard X's initial claim for damages under the State Compensation Act. The District Court ultimately dismissed X's claim.

The Appeal and the New Claim

Dissatisfied with the District Court's ruling, X lodged an appeal with the Fukuoka High Court. It was during these appeal proceedings that X sought to significantly modify the scope of the lawsuit by introducing an additional, alternative claim. This new claim was for "loss compensation" (sonshitsu hoshō), grounded in Article 29, paragraph 3 of the Constitution of Japan. This constitutional provision mandates that just compensation be paid when private property is taken for public use. X asserted that the business losses incurred due to Fukuoka Prefecture's projects amounted to a sum identical to that originally claimed as damages under the State Compensation Act. The PDF commentary refers to this procedural maneuver as a "preliminary and additional joinder" (yobiteki・tsuikateki heigō).

High Court's Stance

The Fukuoka High Court, after deliberation, dismissed X's appeal concerning the original state compensation claim. Furthermore, and critically for the subsequent appeal to the Supreme Court, the High Court also dismissed the newly added loss compensation claim. It deemed the joinder of this distinct type of claim at the appellate stage to be procedurally inadmissible. Following this comprehensive defeat at the High Court, X appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Supreme Court's Decision on "Reverse Joinder"

The Supreme Court's judgment meticulously addressed the permissibility of joining the loss compensation claim to the ongoing state compensation proceedings, particularly focusing on the procedural nuances.

A. The Concept of "Reverse Joinder"

The core procedural challenge before the Supreme Court was the admissibility of what legal commentators often refer to as "reverse joinder" (gyaku heigou).

The Administrative Case Litigation Act (ACLA) of Japan contains explicit provisions that allow for the joinder of related civil law claims (such as a state compensation claim for damages) to a primary administrative lawsuit (for example, a suit seeking the revocation of an administrative disposition) (ACLA Arts. 13, 16, 19). In such scenarios, the administrative claim is the anchor.

However, the ACLA does not contain any specific provision addressing the inverse situation: the addition of a public law claim to an existing civil lawsuit. A loss compensation claim, particularly one based directly on Article 29, paragraph 3 of the Constitution, is generally considered a public law claim, often taking the form of a "substantive party suit" (jisshitsuteki tōjisha soshō) under Article 4 of the ACLA. X's initial lawsuit for damages was a civil claim.

Prior to this Supreme Court ruling, lower courts in Japan had shown a division of opinion on whether such "reverse joinders" were permissible. Some courts had denied such joinders, often reasoning that the ACLA established a specific and distinct framework for administrative litigation where administrative suits were intended to be the primary vehicle, and that allowing civil suits to become the base for public law claims was not envisaged. Other courts, however, had permitted such joinders, particularly in complex cases like those related to vaccine injuries, where the claims often presented a blend of public and private law elements, or where the procedural differences between handling the claims together versus separately were deemed minimal and outweighed by considerations of judicial economy and plaintiff convenience. The High Court in X's case had adopted the stricter, negative view.

B. Supreme Court's Novel Approach: Focusing on the Code of Civil Procedure (CCP)

The Supreme Court, in its 1993 decision, charted a distinct course from many lower court precedents that had grappled with this issue through the lens of the ACLA. Instead of attempting to interpret or extend the ACLA to cover this "reverse joinder" scenario, the Supreme Court framed the question of its permissibility primarily as an issue to be resolved under Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (CCP), specifically looking at the rules governing the amendment of claims during ongoing litigation.

The Court reasoned that the ACLA's provisions on claim joinder were designed for situations where an administrative lawsuit serves as the foundational or base case, and other related claims are joined to it. These ACLA provisions, the Court implied, do not directly address the scenario where a civil lawsuit is the base case and a public law claim is sought to be added.

The Supreme Court stated that the joinder of X's loss compensation claim to the pre-existing state compensation claim should be considered "analogous to" (ni junjite) an additional amendment of claim as permitted under the then-Article 232 of the CCP (which was later revised and is now, in substance, Article 143 of the current CCP).

The Court's use of the phrase "analogous to" is significant. The old CCP Article 232, and the general rule for the objective joinder of claims found in the old CCP Article 227 (now CCP Article 136), generally required that claims could be joined or amended into a proceeding only if they were pursuable under the "same type of litigation procedure" (dōshu no soshō tetsuzuki ni yoru). A state compensation claim, which proceeds under civil litigation rules, and a loss compensation claim, which is a type of administrative party suit with its own procedural characteristics, are not strictly of the "same type.". The Supreme Court, therefore, appeared to be looking beyond strict procedural categorization to the substantial commonalities and connections between the claims in question.

C. Conditions for Permitting Joinder based on "Same Basis of Claim"

The Supreme Court found the joinder of the loss compensation claim to be permissible in principle by examining whether the claims shared the "same basis of claim" (seikyū no kiso)—a key concept for allowing claim amendments under CCP Article 232/143. The Court identified several specific factors that, in this particular case, indicated such a shared basis:

- Same Defendant: Both the original state compensation claim and the proposed loss compensation claim were directed against the same defendant, Y (Fukuoka Prefecture). This was an important factor, as an amendment of claim under the CCP generally does not permit a change of defendants.

- Nature of Relief Sought: Both claims sought monetary payment, and in the context of these claims, the parties (X as plaintiff, Y as defendant state entity) were considered to be on an equal footing for the purpose of the litigation.

- Identity of Economic Disadvantage: The underlying economic disadvantage that X alleged—the business losses stemming from the environmental impact of the public works—was identical for both claims. Furthermore, the amount X claimed under the loss compensation theory was the same as the amount sought under the state compensation theory.

- Common Origin of Claims: Both claims were asserted to have arisen from the same set of actions undertaken by Y—namely, the dam construction and road widening projects. This meant that the factual origin of the dispute was substantially common to both claims.

Given these strong interrelations—same defendant, same type of relief sought (monetary), same alleged economic loss, and a common factual genesis—the Supreme Court concluded that the claims shared the same essential foundation. This common foundation made the joinder, in principle, acceptable by analogy to the CCP rules for amending claims.

D. The Crucial Rider: Defendant's Consent at the Appellate Stage

Despite finding the joinder permissible in principle based on the shared basis of the claims, the Supreme Court introduced a critical and ultimately decisive condition for such joinders when they are attempted at the appellate stage of litigation: the consent of the defendant.

This requirement for the defendant's consent is not an explicit, universal mandate under CCP Article 232/143 for all amendments of claims (which generally focuses on whether the amendment would substantially delay the proceedings or fundamentally change the nature of the dispute beyond the "same basis"). The Supreme Court's imposition of this stricter consent requirement in this specific context was justified by several considerations:

- Public Law Nature of the Added Claim: The Court emphasized that a loss compensation claim, such as the one X sought to add, is a public law claim. As such, it is properly tried under administrative litigation procedures, typically as a substantive party suit.

- Defendant's "Benefit of Tiers of Courts" (shinkyu no rieki): Introducing a new type of claim, especially one with a distinct procedural nature like a loss compensation claim, for the first time at the appeal level could significantly prejudice the defendant's right to have that claim fully litigated through all available judicial tiers, starting from the court of first instance. The PDF commentary elaborates that this concern is particularly relevant because substantive party suits under the ACLA, such as loss compensation claims, have their own unique procedural characteristics. For instance, while ACLA provisions like the court's power to examine evidence ex officio apply, the potential for formal participation of other administrative agencies in the lawsuit (under ACLA Article 23) might be relevant in some loss compensation cases. Additionally, the binding effect of judgments in such cases on related administrative agencies could also be a pertinent factor. Depriving the defendant (and potentially other relevant administrative entities) of a first-instance hearing where these specific aspects could be addressed was seen as potentially unfair.

- Maintaining Parity with ACLA Joinder Rules: The Court also likely considered the need for procedural balance with the ACLA's own rules. The ACLA, when it does allow related civil claims to be joined to a primary administrative suit, generally requires the defendant's consent if that joinder is to occur at the appellate stage (ACLA Art. 41, para. 2, which applies ACLA Art. 19, para. 1, which in turn incorporates ACLA Art. 16, para. 2, stipulating this consent requirement). Requiring consent for this "reverse joinder" scenario at the appeal stage thus aligns with the ACLA's approach to late-stage joinders and ensures a degree of procedural consistency.

E. Application to X's Case and Final Outcome

In X's specific circumstances, Fukuoka Prefecture (Y), the defendant, had explicitly objected to the joinder of the loss compensation claim when X attempted to introduce it at the High Court. Y had argued that the joinder was impermissible and had formally requested its dismissal. Therefore, there was clearly no consent from Y for this late-stage addition of the new claim.

Consequently, the Supreme Court concluded that, due to the lack of Y's consent, the addition of the loss compensation claim at the appellate stage was not permissible in this instance. The Court noted that X's request for joinder was evidently predicated on having both the state compensation claim and the loss compensation claim heard and decided together within the same set of proceedings. Since this combined adjudication was not procedurally possible without the defendant's consent at that stage, the Supreme Court found that the High Court's decision to dismiss the added loss compensation claim as inadmissible was, in its ultimate conclusion, correct. As a result, X's appeal to the Supreme Court was dismissed.

IV. Significance and Implications of the Ruling

The Supreme Court's 1993 decision, while specific to its facts, carried broader implications for understanding the procedural interplay between civil and administrative litigation in Japan.

A. A Bridge, Not a Freeway, for "Reverse Joinder"

The judgment was notable because it acknowledged a potential pathway for "reverse joinder" by drawing an analogy to the CCP's rules on claim amendment, rather than outright rejecting such joinders due to the ACLA's silence on the matter. This approach was interpreted by some legal commentators as a step towards lowering the traditionally somewhat rigid procedural barrier between civil litigation and substantive party suits under administrative law.

However, it is crucial to understand that the ruling did not provide a blanket permission for all types of "reverse joinders". The Supreme Court's willingness to consider the joinder permissible in principle was heavily contingent on the specific facts of the case, particularly the very close factual and legal connections between the two claims, which allowed the Court to find a "same basis of claim.". The Court meticulously listed these connecting factors: the same defendant, the request for monetary relief, the identical nature of the economic loss alleged, and the common factual origin of the claims. This detailed enumeration suggests that future courts would need to undertake a similar case-by-case analysis based on these criteria, rather than applying a general rule that any public law claim can be easily appended to any ongoing civil suit.

B. Emphasis on Procedural Fairness in Appeals

The introduction and application of the defendant's consent requirement for allowing a joinder at the appellate stage prominently underscore the Supreme Court's deep concern for procedural fairness and the protection of what is often termed the "benefit of tiers of courts" (shinkyu no rieki). This principle holds that parties generally have a right to have their case heard and adjudicated through the established hierarchy of the court system, allowing for full factual development at the first instance and review at higher instances.

This concern is particularly acute when the new claim sought to be introduced at a late stage, such as X's loss compensation claim, involves distinct legal principles or procedural features that are characteristic of a different branch of litigation (in this case, administrative litigation). Forcing a defendant to confront such a new claim for the first time on appeal, without the opportunity to address its unique aspects at the trial court level, could lead to significant prejudice.

C. The Ongoing Dialogue between Civil and Administrative Procedure

This case serves as an important illustration of the ongoing interaction, and sometimes the inherent tension, between Japan's Code of Civil Procedure (governing general civil lawsuits) and its Administrative Case Litigation Act (designed to provide specialized procedures for disputes involving the exercise of state power). Real-world situations, like X's, frequently involve elements that straddle the lines between public law and private law.

The PDF commentary touches upon the idea that the distinction between state compensation claims (often viewed as analogous to tort claims for unlawful acts) and loss compensation claims (rooted in constitutional principles of "just compensation" for lawful, but specially burdensome, takings or public actions) can sometimes become blurred. This is particularly so in cases that fall into what is sometimes described by scholars as the "valley" (tanima) between these two established forms of redress—situations where lawful state actions nevertheless cause a "special sacrifice" (tokubetsu no gisei) that may warrant compensation. While the Supreme Court's judgment in X's case did not explicitly base its justification for potential joinder on this "valley" theory, it operated within a legal landscape where such complex, hybrid situations are recognized. The Court's decision can be seen as a pragmatic attempt to find a workable procedural solution for handling closely related claims efficiently, without necessarily requiring plaintiffs to file entirely separate lawsuits, albeit conditioned on strict fairness considerations.

D. Relevance for Future Procedural Reforms

The specific issues addressed in this judgment, and the broader questions of claim joinder they raise, remain highly relevant to ongoing discussions in Japan about how to make the litigation process more efficient, accessible, and effective for citizens seeking redress for harms caused by state actions. The PDF commentary associated with this line of cases concludes by observing that the 2004 amendments to the ACLA were aimed, in part, at expanding and enhancing the protection of citizens' rights. From that perspective, it notes, a re-examination of various theories and rules concerning claim joinder in administrative and civil litigation is necessary. This 1993 Supreme Court decision provides a key historical and jurisprudential reference point in that continuing dialogue about procedural reform and access to justice.

V. Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of July 20, 1993, in the matter involving X and Fukuoka Prefecture, offers significant insights into the procedural intricacies of joining public law claims (specifically, loss compensation claims under the Constitution) to ongoing civil lawsuits (in this instance, state compensation claims under statute) in the Japanese legal system.

By indicating that such "reverse joinder" could be permissible in principle, by way of analogy to the Code of Civil Procedure's rules on the amendment of claims—provided there is a demonstrably close connection establishing a "same basis of claim"—the Court exhibited a degree of procedural flexibility. This was a nod towards judicial economy and the practical realities faced by litigants.

However, this flexibility was carefully counterbalanced by a robust emphasis on procedural fairness. The imposition of a requirement for the defendant's consent for such a joinder to occur at the appellate stage stands as a firm protection for the defendant's right to have all facets of the case properly and fully litigated through the court system's different tiers. It ensures that a party is not unfairly surprised or disadvantaged by the late introduction of a claim with distinct legal and procedural characteristics.

Ultimately, the judgment reflects a pragmatic judicial effort to manage intertwined claims arising from state actions, while diligently navigating the often-complex boundaries and specific procedural regimes of civil and administrative litigation in Japan.