Navigating Probationary Periods in Japan: The Landmark Mitsubishi Jushi Supreme Court Judgment

Judgment Date: December 12, 1973

Case Name: Claim for Confirmation of Labor Contractual Relationship Existence (Known as the Mitsubishi Jushi Case)

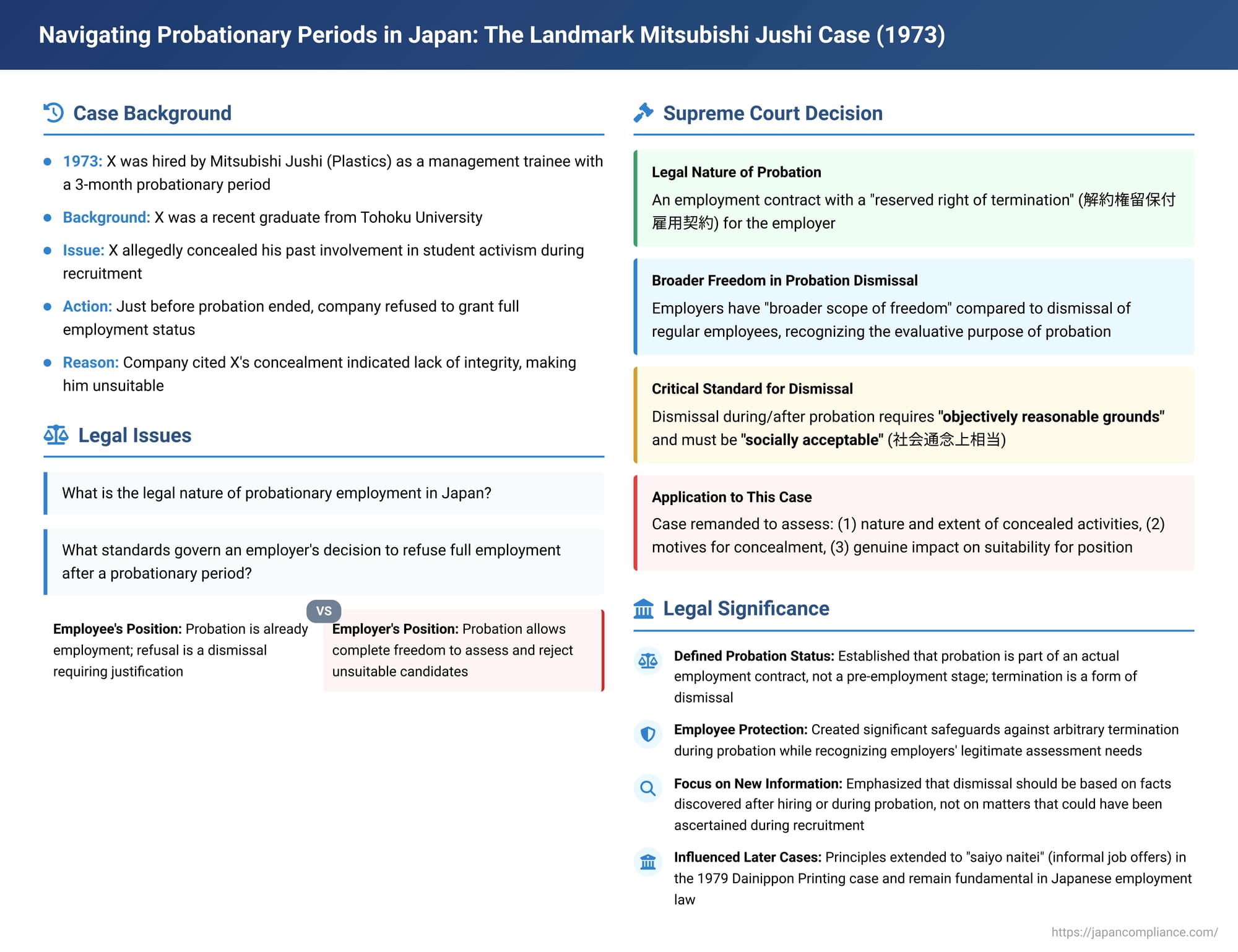

Probationary periods are a common feature in Japanese employment practices, intended to allow employers to assess a new hire's suitability before confirming permanent employment. However, the legal status of employees during this period and the extent of an employer's discretion to refuse full employment have been critical legal questions. The Japanese Supreme Court's Grand Bench judgment in the Mitsubishi Jushi (Mitsubishi Plastics) case, delivered on December 12, 1973, is a foundational ruling that provided significant clarity on these issues, establishing key principles that continue to influence labor law in Japan. While this case also famously dealt with an employer's freedom to inquire into an applicant's beliefs during recruitment, this analysis will focus specifically on the Court's pronouncements regarding the probationary period itself.

Factual Background of the Mitsubishi Jushi Case (Probationary Aspect)

The plaintiff, X, was hired by Company Y, a plastics manufacturer, as a prospective management trainee upon his graduation from Tohoku University. His employment commenced with a stipulated three-month probationary period. However, just before this period was set to expire, Company Y orally informed X that his full, permanent employment would be refused. The primary reason cited by Company Y was X's alleged concealment of his past involvement in student activism during his university years. Company Y argued that this concealment indicated a lack of integrity and rendered him unsuitable for a management position within the company, thus justifying the refusal of full employment.

The lower courts had grappled with the nature of this probationary employment and the legality of Company Y's action. Both the Tokyo District Court and the Tokyo High Court characterized X's initial hiring as an employment contract that included a "reserved right of termination" (解約権留保 - kaiyaku-ken ryūho) for Company Y. This meant Company Y could terminate the contract during the probationary period if it found X unsuitable. Both lower courts ultimately ruled in favor of X, deeming the refusal of full employment (effectively a dismissal) invalid.

The Supreme Court's Rulings on the Probationary Period

The Supreme Court, while ultimately remanding the case for further factual determination regarding the concealment issue, laid down crucial legal principles concerning probationary employment:

- Legal Nature of Probationary Employment: An Employment Contract with a Reserved Right of Termination:

The Supreme Court concurred with the lower courts' characterization of the probationary employment. It emphasized that the legal nature of such an arrangement should be determined not solely by the literal wording of company work rules or employment contracts, but also by considering the actual treatment of probationary employees within the company and any established practices regarding their transition to full employment.

In Company Y's case, there was a history of new university graduates consistently transitioning to full employment after their probation, and no separate employment contract was typically executed upon confirmation; rather, a simple formal notice of assignment (辞令 - jirei) was issued. Based on these factual circumstances, the Court found it justifiable to view X's probationary employment as an employment contract with a reserved right of termination for the employer.

This finding was significant because it meant that the refusal to grant full employment at the end of the probationary period was not merely a decision not to enter into a new contract, but rather the exercise of a right to terminate an existing one—in other words, a form of dismissal. - Rationale and General Validity of Probationary Periods:

The Court acknowledged the practical utility and general reasonableness of employers utilizing probationary periods, particularly when hiring new university graduates. It recognized that at the initial recruitment stage, it is often difficult for an employer to thoroughly assess a candidate's aptitude, character, abilities, and overall suitability for a specific role, especially a management track position. A probationary period allows the employer to observe the employee's performance and conduct, and to gather further information, before making a final decision on permanent employment. The Court affirmed that such clauses reserving the right to terminate are generally valid and enforceable, provided the probationary period is of a reasonable duration. - "Broader Freedom" of Dismissal During Probation, Yet Subject to Strict Limitations:

The Supreme Court stated that a dismissal based on a reserved right of termination during a probationary period generally affords the employer a "broader scope of freedom" compared to the dismissal of a regular, fully confirmed employee. This acknowledges the evaluative purpose of probation.

However, this broader freedom is by no means absolute or unfettered. The Court immediately qualified this by imposing significant limitations, drawing on several considerations:- The general legislative intent in labor law to distinguish between the employer's freedom at the initial hiring stage and the stricter constraints on dismissing an employee once an employment relationship has been established.

- The typically superior bargaining position of the employer when an employment contract (even one with a probationary period) is concluded.

- The legitimate expectations of the employee. An individual who accepts probationary employment typically does so with the anticipation of continued, permanent employment if they perform satisfactorily, and in doing so, they often forgo other employment opportunities.

- The "Objectively Reasonable and Socially Acceptable" Standard for Probationary Dismissal:

Synthesizing these considerations, the Supreme Court established a crucial standard: the exercise of a reserved right to terminate during or at the end of a probationary period is permissible only if there exist objectively reasonable grounds for the dismissal, and the dismissal is considered socially acceptable (justifiable in light of common societal norms), when viewed in light of the purpose for which the right of termination was originally reserved.

The Court elaborated that this means an employer can validly exercise its reserved right of termination if, based on facts discovered after the initial hiring decision or observed during the probationary period—facts that were not known and could not reasonably have been expected to be known at the time of hiring—it is objectively reasonable to conclude that retaining the individual in employment would be inappropriate. - Application to X's Case and Remand:

In X's specific situation, Company Y claimed that his concealment of past student activism rendered him unsuitable. The Supreme Court stated that whether such concealment constituted an "objectively reasonable ground" for dismissal was not a simple matter. It would depend on a comprehensive assessment of various factors, including:- The precise nature, content, and extent of the concealed student activities (particularly whether any of these activities were illegal).

- X's motives and reasons for the concealment.

- How these concealed facts, and the act of concealment itself, would genuinely impact an objective evaluation of X's future conduct, reliability, and overall suitability as a management trainee for Company Y.

Because the High Court had based its decision on the erroneous premise that Company Y's inquiries into X's beliefs were illegal per se, it had not adequately examined these factual issues. The Supreme Court, therefore, remanded the case for a more thorough factual inquiry to determine if Company Y's refusal of full employment met the "objectively reasonable and socially acceptable" standard.

Analysis and Enduring Significance of the Probationary Period Doctrine

The Mitsubishi Jushi judgment has become a cornerstone of Japanese labor law concerning probationary periods, offering both a framework for their use and vital protections for employees.

- Defining the Legal Status of Probation:

The case was pivotal in solidifying the prevailing legal view that a probationary period is not a pre-employment stage but rather part of an actual employment contract—specifically, an employment contract with a reserved right of termination. This characterization ensures that employees under probation are not in a legal vacuum and that any termination is treated as a dismissal, subject to legal scrutiny, rather than a mere non-commencement of a future contract. - Balancing Employer Assessment Needs with Employee Protection:

The Supreme Court sought to strike a balance. It recognized the legitimate need for employers to assess new hires, particularly those with limited track records like recent graduates. This justifies the "broader freedom" in dismissal compared to regular employees. However, by imposing the "objectively reasonable and socially acceptable" standard, it significantly curbed arbitrary terminations, protecting employees' reliance interests and their investment in the new role. - The Stringent Standard for Probationary Dismissal:

While the term "broader freedom" might suggest a significantly lower bar for dismissal, the practical application of the "objectively reasonable and socially acceptable" standard means that employers must have compelling, concrete, and typically newly discovered reasons for not confirming an employee. Mere subjective dissatisfaction is insufficient. The grounds must be objectively justifiable and align with the evaluative purpose of the probation.

Subsequent legal scholarship and some court decisions have even suggested that certain factors, such as those that could have been readily assessed during the initial recruitment process or very general aspects of personality or cooperativeness (unless severely problematic), should not typically form the basis for a valid probationary dismissal. This further narrows the practical ease of such dismissals. - Influence on Broader Employment Law (e.g., "Saiyo Naitei"):

The principles established in Mitsubishi Jushi regarding reserved termination rights and the standard for their exercise have had a wider impact. Notably, the later Supreme Court decision in the Dainippon Printing case (1979) explicitly drew an analogy between the status of an employee during a probationary period and that of an individual who has received a "saiyo naitei" (an informal job offer common for new graduates). This extended a similar protective framework to "naitei" cancellations. - Ongoing Debates and Evolving Application:

- Justification for New Graduates: Some legal scholars have continued to debate the inherent reasonableness of applying probationary periods to new graduates who lack prior work experience. The argument is that their suitability is often based on future potential and adaptability, which may be difficult to accurately assess within a short probationary timeframe through "experimental" employment. This debate influences the strictness with which courts scrutinize the reasons for not confirming such employees.

- Application to Different Employee Categories: While the Mitsubishi Jushi case involved a new graduate hired as a management trainee, its principles are applied more broadly. However, the specific application may vary. For instance, in cases involving mid-career hires for roles requiring specific technical skills or experience, courts might be more inclined to find a probationary dismissal reasonable if there's clear evidence of a significant deficiency in those expected core competencies.

- Dismissal Mid-Probation: Some lower court judgments, like the News Securities High Court decision, have suggested that a dismissal occurring during the probationary period (as opposed to at its conclusion) might be subject to an "even higher degree of reasonableness and social acceptability," given that the full period of assessment has not been completed.

- Extension of Probationary Periods:

The status of an employee during probation is inherently less secure than that of a fully confirmed employee. Therefore, the unilateral extension of a probationary period by an employer is generally viewed with caution. Such extensions are typically considered permissible only if there is a clear basis in the employment contract or work rules (specifying the possibility, reasons, and duration of extension), and often only if the extension is genuinely for the employee's benefit (e.g., to provide more time to demonstrate improvement) and accompanied by clear explanations of the conditions for eventual confirmation. The potential psychological stress on employees due to prolonged uncertainty was highlighted in a Sapporo District Court case (Cares Sapporo), where an extended probationary period under ambiguous circumstances was linked to a work-related suicide.

Concluding Thoughts

The Mitsubishi Jushi Supreme Court judgment remains a critical reference point for understanding probationary employment in Japan. It established that while probationary periods serve a legitimate employer interest in assessing new hires, the decision to terminate employment during or at the end of this period is not left to the employer's unfettered discretion. The "objectively reasonable and socially acceptable" standard provides a significant safeguard for employees, ensuring that dismissals are based on genuine, demonstrable unsuitability discovered or confirmed during the trial period. As employment practices continue to evolve with a greater diversity of hiring patterns and employment types, the foundational principles laid down in Mitsubishi Jushi regarding fairness, objective justification, and the balance of interests in the probationary context retain their enduring importance.