Product-by-Process Claim Clarity in Japan: Drafting Challenges & Best Practices

TL;DR

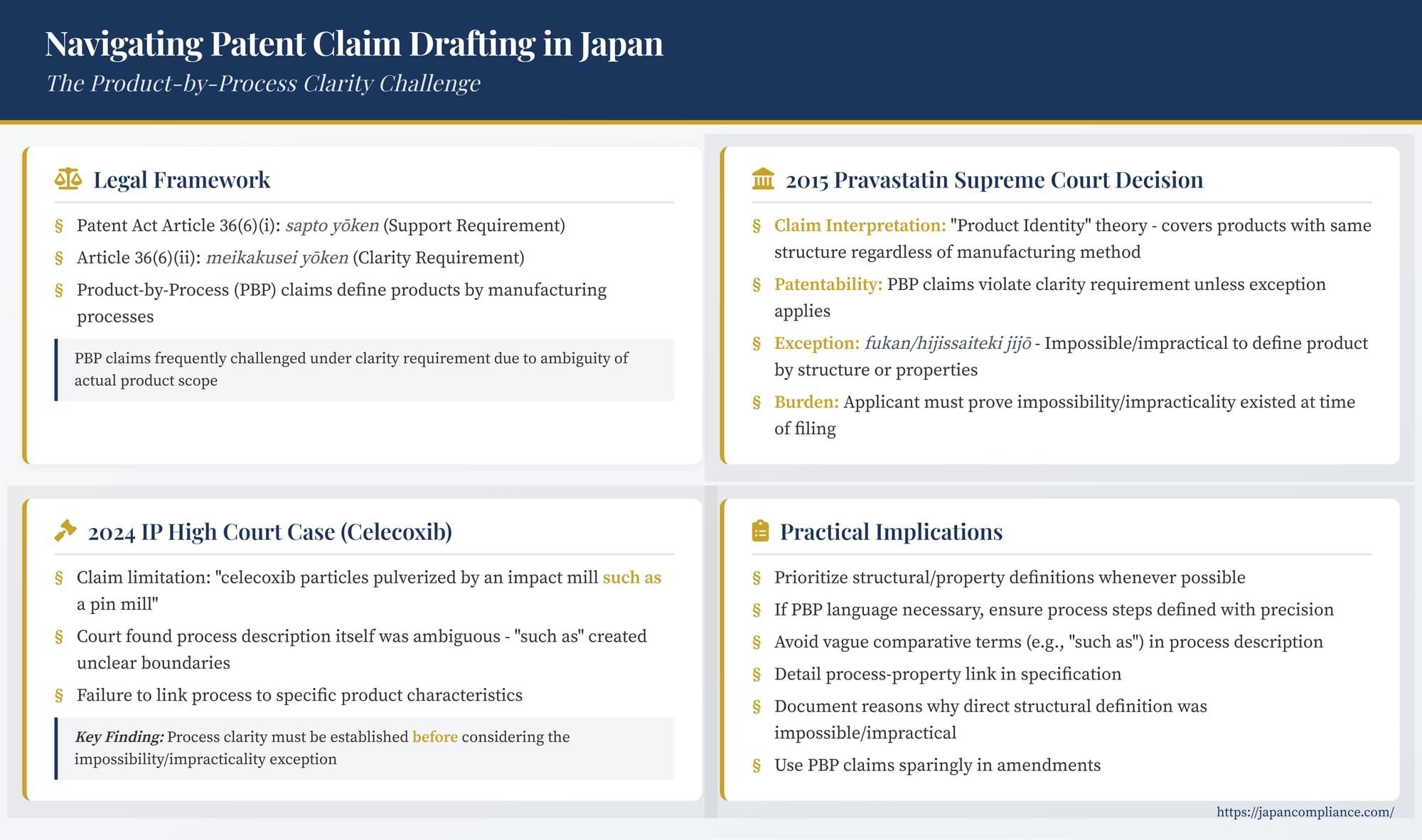

- Japan applies a uniquely strict clarity test to product-by-process (PBP) claims after the 2015 Pravastatin decision and the IP High Court’s 2024 Celecoxib case.

- A PBP claim is allowed only if defining the product by structure/properties was impossible or impractical at filing and the recited process itself is unambiguous.

- Applicants should prioritise structural definitions, draft crystal-clear process language and document “impossibility” justifications before filing or amending.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Importance of Precision in Patent Claims

- The Japanese Legal Framework for PBP Claims

- The Cornerstone: The Pravastatin Supreme Court Decision (June 5 2015)

- Case Study: The Celecoxib Composition Clarity Issue (IP High Court, Mar 18 2024)

- Analysis and Implications for Patent Practice

- Practical Advice for Drafting and Prosecution in Japan

- Conclusion: Precision is Key for PBP Claims in Japan

Introduction: The Importance of Precision in Patent Claims

Securing robust patent protection is fundamental for innovative companies, particularly in technology-intensive fields like pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, and materials science. The claims of a patent define the legal scope of the invention, and their clarity is paramount for ensuring enforceability and legal certainty. However, drafting clear claims can be challenging, especially when an invention relates to a product that is difficult to define solely by its structure or inherent properties.

In such situations, applicants sometimes resort to Product-by-Process (PBP) claims. These are claims directed to a product (mono or 物 in Japanese) but which define that product, at least in part, by reference to the manufacturing process used to obtain it. While potentially useful when structural or property-based definitions are elusive, PBP claims carry inherent risks of ambiguity regarding the actual scope of protection granted.

Different jurisdictions approach PBP claims differently. Japan, following a landmark Supreme Court decision in 2015, adopts a particularly stringent approach, placing significant hurdles on the patentability of PBP claims, primarily concerning the requirement for claim clarity under its Patent Act. A recent Intellectual Property (IP) High Court decision (March 18, 2024) further illuminates these challenges, highlighting that even before considering the established exceptions, the process description itself within a PBP claim must be unambiguous.

For US companies and practitioners involved in filing and prosecuting patents in Japan, understanding these demanding requirements for PBP claims is crucial for developing effective IP strategies and avoiding potential pitfalls during examination or post-grant challenges.

The Japanese Legal Framework for PBP Claims

The key statutory provisions governing claim requirements in Japan are found in Article 36 of the Patent Act:

- Article 36(6)(i): Support Requirement (サポート要件, sapōto yōken): The claimed invention must be supported by the detailed description of the invention provided in the specification. This means the specification must disclose the invention sufficiently to enable a person skilled in the art to recognize that the problem addressed by the invention can be solved by the claimed features.

- Article 36(6)(ii): Clarity Requirement (明確性要件, meikakusei yōken): The invention for which a patent is sought must be "clear" (meikaku, 明確). This requires that the boundaries of the claimed invention be unambiguous, allowing third parties to reasonably determine what falls within the scope of the patent right and what does not.

PBP claims frequently face challenges under the clarity requirement (Art. 36(6)(ii)) because defining a product by its process can obscure the actual product intended for protection.

The Cornerstone: The Pravastatin Supreme Court Decision (June 5, 2015)

The modern understanding and practice regarding PBP claims in Japan are fundamentally shaped by the Supreme Court's judgment in the Pravastatin Sodium case (Supreme Court decision, June 5, 2015, Minshu Vol. 69, No. 4, p. 700). This decision addressed both how PBP claims should be interpreted for infringement purposes and the requirements for their patentability.

1. Claim Interpretation (for Infringement)

The Supreme Court adopted the "product identity" theory for infringement. It held that the technical scope of a PBP claim covers all products that possess the same structure and properties as the product obtained through the process recited in the claim, regardless of the actual manufacturing process used by the alleged infringer. This means if an accused product is structurally identical to the patented product (even if made by a different process), it infringes the PBP claim.

2. Patentability Requirements (Clarity Focus)

While seemingly broad for infringement, the Supreme Court imposed very strict conditions on the patentability of PBP claims, primarily based on the clarity requirement (Art. 36(6)(ii)):

- General Lack of Clarity: The Court reasoned that defining a product by its manufacturing process is generally unclear because the process description often fails to adequately specify the resulting product's actual structure or properties. Third parties cannot reliably determine the scope of the protected product based solely on the process language.

- The Impossibility/Impracticality Exception (不可能・非実際的事情, fukanō / hijissaiteki jijō): Consequently, the Court ruled that using PBP language to define a product is only permissible if, at the time of filing the patent application, it was impossible or practically infeasible for the applicant to define the product directly and adequately by its structure or properties.

- "Impossible" refers to situations where the structure/properties cannot be analyzed or identified with existing technology.

- "Impractical" refers to situations where attempting to define by structure/properties would require an excessive amount of effort or cost that would be unrealistic to expect from an applicant.

- Burden of Proof: Crucially, the burden lies squarely on the applicant or patentee to prove that such "impossibility or impracticality" existed at the time of filing if the PBP claim is challenged during examination or in invalidity proceedings.

Impact of Pravastatin

This decision dramatically changed PBP practice in Japan. Prior to Pravastatin, PBP claims were used more liberally. Post-Pravastatin, the Japan Patent Office (JPO) examiners and the courts rigorously apply the impossibility/impracticality test. Applicants seeking to use PBP claims face a high threshold and must be prepared to strongly justify why a direct structural or property-based definition was not feasible at the time of filing. Failure to meet this burden typically results in rejection or invalidation based on lack of clarity.

Case Study: The Celecoxib Composition Clarity Issue (IP High Court, March 18, 2024)

A recent decision by a panel of the IP High Court (Case Nos. Reiwa 4 (Gyo-Ke) 10127-10130, Reiwa 5 (Gyo-Ke) 10027) further refines the understanding of PBP claim requirements, adding another layer to the clarity analysis.

Background

- The patent at issue concerned pharmaceutical compositions containing celecoxib, an anti-inflammatory drug.

- The patent had previously been involved in invalidity proceedings where claims were found to lack support under Art. 36(6)(i).

- In response, during reopened invalidity proceedings, the patent owner (Defendant Y) requested amendments to the claims. Amended Claim 1 included, among other features related to particle size (D90 of 30µm) and excipients (including sodium lauryl sulfate), the following limitation: "wherein the celecoxib particles are those pulverized by an impact mill such as a pin mill" (「セレコキシブ粒子が、ピンミルのような衝撃式ミルで粉砕されたものであり、」). This was the key PBP feature ("the pin mill feature").

- The patent owner argued this specific pulverization process imparted desirable properties like reduced particle agglomeration and improved blend uniformity compared to other milling methods.

- The JPO allowed the amendments and maintained the patent, finding that the PBP claim met the clarity requirement because the impossibility/impracticality exception applied (i.e., defining the resulting particle properties directly was deemed difficult).

- Opponents (Plaintiffs X, including Teva) filed suit seeking cancellation of the JPO's decision, arguing, among other things, that the amended claim still lacked clarity (Art. 36(6)(ii)) and support (Art. 36(6)(i)).

The IP High Court's Decision on Clarity

The IP High Court overturned the JPO's decision, finding that Amended Claim 1 lacked clarity under Article 36(6)(ii). Its reasoning focused not on the Pravastatin impossibility/impracticality test, but on the ambiguity of the process description itself:

- PBP Nature Confirmed: The court agreed that the "pin mill feature" was PBP language, attempting to define the product (celecoxib particles) by reference to a manufacturing process.

- Ambiguity of the Recited Process: The core problem identified by the court was that the phrase "pulverized by an impact mill such as a pin mill" was inherently unclear.

- Lack of Link to Properties: While the patent specification mentioned benefits like reduced agglomeration and improved uniformity resulting from pin milling, it failed to adequately explain how this specific process achieved these results or, more importantly, what specific structural or physical characteristics distinguished pin-milled particles from those produced by other milling techniques. Without this link, the process description didn't clearly define a specific product structure or property set.

- Ambiguous Scope of "Such As": The phrase "an impact mill such as a pin mill" (ピンミルのような衝撃式ミル) was deemed fatally ambiguous. The specification provided no criteria or guidance for determining which other types of impact mills would qualify as being "like" a pin mill for the purpose of obtaining the desired particle properties. Does it refer to mills with similar mechanisms, energy inputs, or simply any mill capable of producing particles with the mentioned (but vaguely defined) properties? As the court noted, without clear guidance on how to determine if a given impact mill falls within the scope of "such as a pin mill," the boundary of the resulting product defined by this process term was unclear.

- Clarity Failure Precedes Pravastatin Test: Because the process description itself was ambiguous, the court concluded that the claim failed the clarity requirement of Article 36(6)(ii) before even needing to consider the Pravastatin impossibility/impracticality exception. The JPO's error was in proceeding to the impossibility/impracticality analysis without first ensuring the process term itself was clear.

Comments on Support Requirement

Although finding the claim invalid for lack of clarity was sufficient to overturn the JPO decision, the court briefly addressed the support requirement (Art. 36(6)(i)) as well, likely to provide guidance for potential future proceedings. It stated that if the unclear "pin mill feature" were disregarded, the remaining elements of the claim (specific particle size D90, presence of sodium lauryl sulfate, etc.) were described in the specification in a manner sufficient for a skilled person to understand that the invention could solve the stated problem (improving bioavailability). This suggests the underlying invention, defined by particle size and formulation, might have been patentable if claimed directly, but the flawed PBP language rendered the claim invalid.

Analysis and Implications for Patent Practice

This IP High Court decision reinforces the strict scrutiny applied to PBP claims in Japan and adds an important preliminary step to the analysis:

- Process Clarity is Paramount: The case establishes that the manufacturing process recited in a PBP claim must itself be clear and unambiguous. If the scope of the process steps or the equipment used (especially when defined using comparative or exemplary language like "such as") is unclear, the claim can fail the clarity requirement under Art. 36(6)(ii) regardless of whether the Pravastatin impossibility/impracticality exception might otherwise apply. Ambiguity in the process leads directly to ambiguity in the product defined thereby.

- Importance of Linking Process to Product Features: While not the primary basis for the clarity rejection in this case, the court's difficulty in understanding how the pin mill process led to specific properties highlights the importance of clearly articulating this link in the specification. Explaining the structural or property-related consequences of the claimed process helps demonstrate the technical significance of the PBP feature and potentially supports arguments for its necessity (impossibility/impracticality).

- High Bar for PBP Claims Remains: The decision confirms that PBP claims are disfavored in Japan. Applicants must prioritize defining products by their structure or properties whenever feasible. Resorting to PBP language requires not only meeting the strict Pravastatin impossibility/impracticality test but also ensuring the process description itself is crystal clear.

- Risks of PBP Amendments: Introducing PBP limitations during prosecution or post-grant amendments to distinguish over prior art or address support/enablement issues is fraught with risk. As this case shows, poorly drafted or ambiguous process language can create fatal clarity defects, potentially invalidating the entire claim. The amendment intended to save the patent ended up being its downfall on clarity grounds.

Practical Advice for Drafting and Prosecution in Japan

Given the stringent requirements, companies and practitioners should adopt the following strategies when dealing with potential PBP claims in Japan:

- Prioritize Structural/Property Definitions: Make every effort to define the invention directly by its chemical structure, physical properties, parameters, or a combination thereof. PBP language should be a true last resort.

- Ensure Process Clarity: If PBP language is deemed absolutely necessary, define the process steps with utmost precision. Avoid vague terms, open-ended lists, or comparators like "such as" unless the specification provides a clear, objective basis for determining the scope (e.g., defining the class of "similar" mills by specific functional or operational parameters linked to the desired outcome).

- Detail the Process-Property Link: Explicitly describe in the specification how the specific process steps lead to unique or advantageous structures or properties in the final product that cannot be readily achieved or defined otherwise.

- Prepare Justification for Impossibility/Impracticality: If relying on the Pravastatin exception, meticulously document the reasons why direct structural/property definition was impossible or impractical at the time of filing. This might include records of analytical challenges, failed attempts at characterization, or explanations of why known parameters were insufficient to distinguish the invention. This justification should be included in or readily available from the application as filed or related documents.

- Use PBP Sparingly in Amendments: Be extremely cautious when introducing PBP features via amendment. Ensure the added language is precise and consider whether the impossibility/impracticality burden can realistically be met for the amended claim scope.

Conclusion: Precision is Key for PBP Claims in Japan

Japan's patent law demands a high degree of clarity in claim drafting, and this standard is applied with particular rigor to Product-by-Process claims. While the landmark Pravastatin decision established the stringent "impossibility/impracticality" exception as a prerequisite for allowing PBP definitions, the recent Celecoxib composition decision from the IP High Court adds a crucial reminder: the clarity analysis starts even earlier. The manufacturing process recited within the PBP claim must itself be unambiguous before the question of whether defining the product directly was possible is even reached.

For technology companies seeking patent protection in Japan, especially in fields where PBP claims might seem tempting, this necessitates a disciplined approach. Prioritize direct structural or property-based claiming wherever possible. If PBP language is unavoidable, ensure the process description is meticulously clear and unambiguous, thoroughly explain the resulting product characteristics in the specification, and be prepared to robustly defend the impossibility or impracticality of alternative definitions based on the state of the art at the time of filing. Navigating Japan's PBP requirements demands precision in both technical understanding and legal drafting.

- Patent Litigation Across the Pacific: Key Differences Between the US and Japanese Systems

- Balancing Innovation and Security: Strategic IP and R&D Adjustments Under Japan's Patent Non-Disclosure System

- Decoding Japanese IP Law: How Judicial Interpretation Shapes Patent, Trademark and Copyright Cases

- Product-by-Process Claims – Examination Guidelines (JPO)