Navigating New Rules: A Local Government's Duty of Consideration to Businesses – The 2004 K Town Case

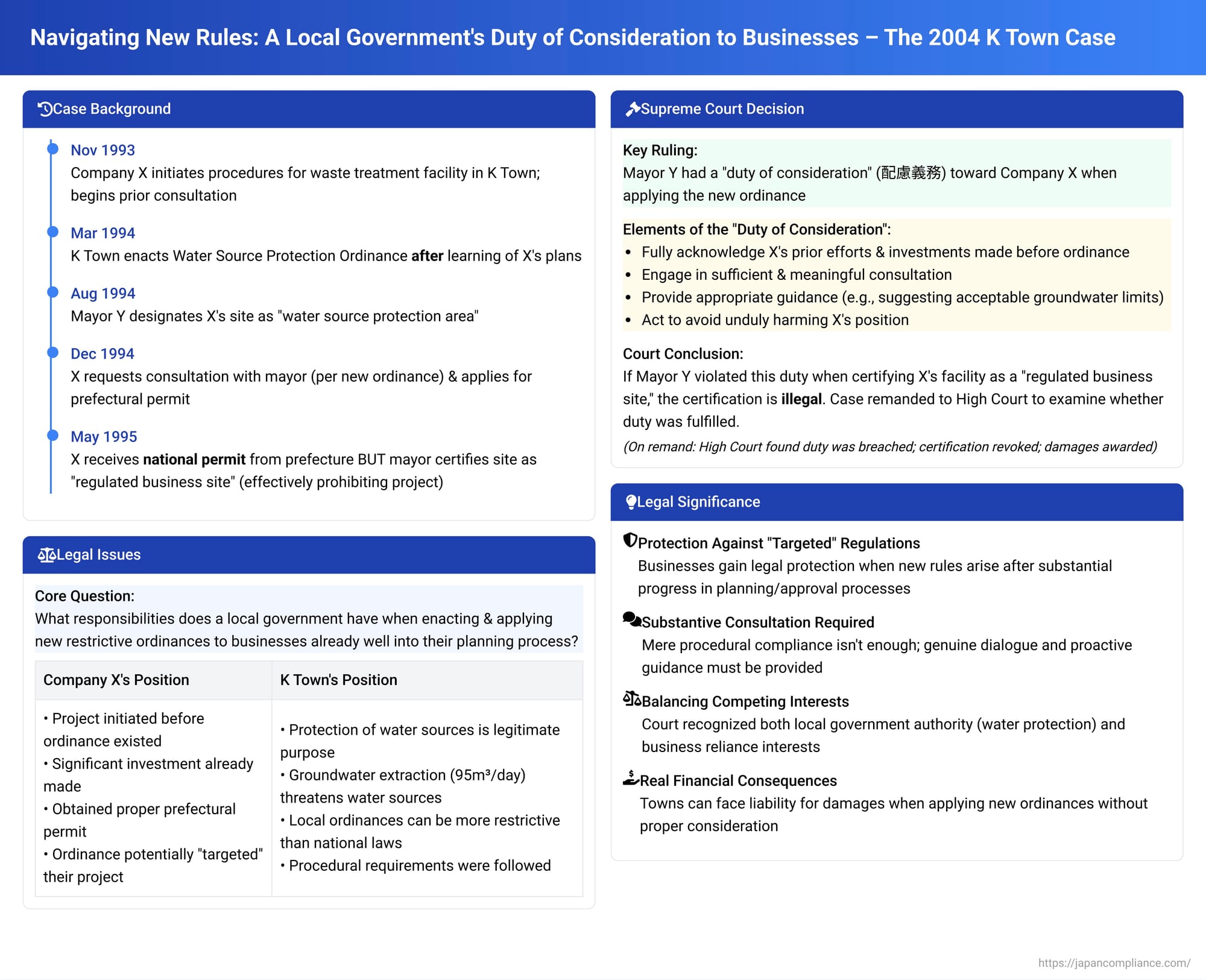

Businesses often face a challenging landscape where regulations can change, sometimes after substantial investment in a project has already been made. A key question arises: what responsibilities do local governments have towards businesses caught in such a transition? A Japanese Supreme Court decision on December 24, 2004, shed light on this issue, establishing that local authorities may have a "duty of consideration" (hairyo gimu) when new ordinances impact entities already well into their planning and approval processes.

The Case Background: A Waste Treatment Project Meets a New Ordinance

The dispute involved Company X, an industrial waste treatment operator, and K Town, a municipality in Mie Prefecture[cite: 1, 2].

- Project Initiation and Initial Consultations: Company X planned to construct an intermediate industrial waste treatment facility within K Town[cite: 1, 2]. In November 1993, X submitted its business plan for this facility to the director of the Mie Prefectural Owase Health Center, initiating the necessary administrative procedures[cite: 1, 2]. Following this, prior consultation meetings (jizen kyōgi) were held. These meetings involved Company X, relevant departments of Mie Prefecture, and officials from K Town[cite: 1, 2].

- Enactment of a New Local Ordinance: Through these consultations, K Town became aware of Company X's specific plans. Subsequently, in March 1994, the K Town assembly enacted the "K Town Water Source Protection Ordinance" (Suidō Suigen Hogo Jōrei)[cite: 1, 2]. This ordinance was aimed at protecting the town's drinking water sources by preventing water pollution and source depletion[cite: 2]. It empowered the mayor to designate "K Town Water Source Protection Areas" and prohibited the establishment of "regulated business sites" (kisei taishō jigyōjō) within these areas[cite: 1, 2]. A "regulated business site" was defined as a factory or other business establishment that, in the mayor's judgment, posed a risk of polluting water sources or causing their depletion[cite: 1, 2]. Violations could lead to penalties, including imprisonment or fines[cite: 2].

- Site Designation and Further Procedures: Company X's proposed construction site for the waste treatment facility was subsequently designated by the Mayor of K Town (Y) as a water source protection area in August 1994[cite: 1, 2]. The new ordinance required businesses intending to operate "target businesses" (which included industrial waste treatment) within a protected area to consult with the mayor and take steps like holding informational meetings for local residents before establishing the facility[cite: 2].

- Conflicting Approvals and a Local Roadblock:

- On December 22, 1994, Company X, adhering to the new K Town ordinance, formally requested a consultation with Mayor Y[cite: 1, 2].

- Concurrently, on December 27, 1994, Company X applied to the Governor of Mie Prefecture for a permit to install the industrial waste treatment facility, as required under the national Waste Management Act (specifically, the version prior to the 1997 amendment)[cite: 1, 2]. Company X successfully obtained this prefectural permit on May 10, 1995[cite: 1, 2].

- However, the local process in K Town took a different turn. Mayor Y, after receiving Company X's consultation request, sought the opinion of the K Town Water Source Protection Council, as mandated by the ordinance[cite: 2]. This council, noting Company X's plan to withdraw 95 cubic meters of groundwater per day for its operations, advised the mayor that the facility should be deemed a regulated business site[cite: 1, 2].

- Consequently, on May 31, 1995, Mayor Y issued an administrative disposition (shobun) certifying Company X's proposed facility as a "regulated business site." The stated reason was that the facility "would or could cause the depletion of water sources"[cite: 1, 2]. This certification, under the K Town ordinance, effectively prohibited Company X from constructing the facility, despite having received the necessary permit from Mie Prefecture under national law[cite: 1, 2].

- Legal Challenge: Unable to proceed with the project, Company X filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of Mayor Y's "regulated business site" certification[cite: 1, 2].

Lower Courts: Upholding the New Ordinance and Certification

The initial court battles did not favor Company X:

- Both the Tsu District Court (first instance) and the Nagoya High Court (second instance) ruled that Mayor Y's certification was lawful and dismissed Company X's claim[cite: 1]. These courts focused on the legitimate objective of the K Town ordinance – the protection of water sources – and found that the mayor's decision, based on the potential impact of X's proposed groundwater usage, was valid.

Company X then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Decision: Emphasizing the Duty of Consideration

The Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment of December 24, 2004, reversed the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further examination[cite: 2]. The Supreme Court's reasoning centered on a "duty of consideration" owed by the mayor to Company X.

Context of the Ordinance's Enactment

The Supreme Court meticulously noted the sequence of events:

- The K Town Water Source Protection Ordinance was enacted after K Town authorities had become aware of Company X's specific plans to build the waste treatment facility. This awareness came through the town's participation in the prior consultation meetings related to X's application for a permit under the national Waste Management Act[cite: 2].

- Mayor Y was therefore cognizant of the fact that Company X had already initiated and progressed significantly in the procedures for obtaining the prefectural installation permit before the new local restrictive ordinance came into existence[cite: 2].

- The Court pointed out that through these earlier prefectural consultations, K Town had been afforded an opportunity to consider what measures it should take to harmonize the perceived need for X's facility with the town's objective of protecting its water sources[cite: 2].

Importance of Procedural Fairness (The Consultation Process)

The Supreme Court highlighted that the K Town ordinance itself established important procedural safeguards:

- It required businesses intending to undertake "target事業" (target businesses, including waste treatment) within a designated water source protection area to engage in prior consultation with the mayor[cite: 2].

- It also mandated that the mayor, before certifying a facility as a "regulated business site," must seek the opinion of the K Town Water Source Protection Council and make a careful and deliberate judgment[cite: 2].

- Considering that a certification as a "regulated business site" imposes substantial restrictions on a business operator's rights, the Court deemed this consultation process to be a procedure of significant importance within the framework of the ordinance[cite: 2].

The Emergence of a "Duty of Consideration" (Hairyo Gimu)

Based on this factual background and the procedural requirements of the ordinance, the Supreme Court found that a specific duty arose for Mayor Y:

- Given K Town's awareness of Company X's advanced stage of planning and its prior engagement in the prefectural permitting process before the town enacted its restrictive ordinance, the Supreme Court ruled that Mayor Y, in deciding on Company X's certification, had a "duty of consideration" (配慮すべき義務があった - hairyo subeki gimu ga atta) towards Company X[cite: 2].

- This duty required Mayor Y, during the consultation process stipulated by the town's own ordinance, to:

- Fully acknowledge and take into account Company X's specific circumstances, including its prior efforts and investments made on the assumption of the then-existing regulatory landscape[cite: 2].

- Engage in sufficient and meaningful discussions and consultations (十分な協議を尽くし - jūbun na kyōgi o tsukushi) with Company X[cite: 2].

- Provide appropriate guidance (適切な指導をし - tekisetsu na shidō o shi) to Company X. For instance, the mayor should have proactively explored ways to make Company X's project compatible with the new ordinance's water protection objectives. This could have involved urging Company X to limit its proposed groundwater withdrawal to an acceptable level or to consider and implement alternative water usage plans or mitigation measures[cite: 2].

- Act in a manner that would not unduly harm Company X's position (Xの地位を不当に害することのないよう - X no chii o futō ni gaisuru koto no nai yō)[cite: 2].

Consequences of Breaching the Duty of Consideration

The Supreme Court stated unequivocally that if Mayor Y's certification of Company X's facility as a "regulated business site" was made in violation of this duty of consideration, then the certification itself would be illegal (違法となる - ihō to naru)[cite: 2].

Remand for Re-examination

The Supreme Court found that the Nagoya High Court, in its prior ruling, had failed to assess the legality of Mayor Y's action from this crucial perspective of the duty of consideration[cite: 2]. Therefore, the High Court's judgment was reversed, and the case was remanded for a new hearing. The Nagoya High Court was instructed to re-examine the case, focusing specifically on whether Mayor Y had fulfilled this duty of consideration owed to Company X[cite: 2].

Analysis and Implications

The Supreme Court's 2004 decision in this case is highly significant for several reasons:

- Protection for Businesses Facing New, Potentially "Targeted" Regulations: While the Supreme Court did not explicitly label the K Town ordinance as a "sniper ordinance" (neraiuchi jōrei) designed solely to block Company X, its strong emphasis on the fact that the town enacted the restrictive ordinance after becoming aware of X's specific, advanced plans is noteworthy[cite: 2]. The ruling provides a potential avenue for relief for businesses that find themselves disproportionately affected by new local regulations that emerge after substantial progress has been made on a project. The legal commentary suggests that the general validity of the ordinance for its stated purpose of water protection was likely accepted by the Court, but its specific application to Company X, given the history, demanded special care and consideration from the mayor[cite: 1].

- Substantive Content of the "Duty of Consideration": This duty, as articulated by the Court, is not merely a passive or formal obligation. It requires active engagement from the regulatory authority. This includes genuine dialogue, a proactive exploration of alternatives and modifications, and the provision of constructive guidance to help the business operator potentially comply with the new regulatory objectives, rather than an immediate resort to prohibition without such efforts[cite: 2].

- Importance of Adhering to Procedural Safeguards: The case underscores that procedural requirements within ordinances, such as mandatory consultation periods, are not mere administrative checklist items. They are critical components for ensuring fairness and considered decision-making, especially when new regulations have the potential to significantly impact existing plans and investments[cite: 2].

- Navigating National vs. Local Regulatory Conflicts: The facts highlighted a common tension where a business might secure necessary permits under national laws (administered by the prefecture, in this case the Waste Management Act permit) only to be stymied by a more restrictive local ordinance[cite: 1, 2]. While this Supreme Court decision did not delve into a direct conflict-of-laws analysis between the Waste Management Act and the K Town ordinance (an issue that has been central in other similar cases, as noted in the commentary [cite: 2]), it effectively addressed the fairness of the local ordinance's application in light of the pre-existing national-level process.

- Focus on Lawful Application, Not Just Ordinance Validity: A key aspect of the Supreme Court's nuanced approach was that it did not invalidate the K Town Water Source Protection Ordinance itself. Instead, the focus was sharply on the legality of the mayor's administrative disposition (the certification) in applying that ordinance to Company X. This implies that an otherwise valid local ordinance can be applied in an unlawful manner if the implementing authority fails in its specific duty of consideration to an affected party under particular circumstances, such as those present in Company X's situation.

- Tangible Consequences of Breaching the Duty (Outcome on Remand): The legal commentary accompanying the case summary provides valuable follow-up information[cite: 3]. On remand, the Nagoya High Court (in a February 2006 decision) found that Mayor Y had indeed breached the duty of consideration owed to Company X. The court determined that the town had not engaged in sufficient or appropriate consultations and had failed to offer adequate guidance. Consequently, the High Court revoked the "regulated business site" certification as illegal. Furthermore, the commentary notes that Company X was later successful in a separate state compensation lawsuit against K Town, recovering actual damages resulting from the unlawful certification. This subsequent outcome underscores the real and significant financial consequences for a local government that fails to meet its duty of consideration.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court of Japan's 2004 decision in the K Town case marks an important development in administrative law, particularly concerning the relationship between local governments and businesses affected by new regulations. It establishes that when a municipality enacts and applies new rules that significantly impact businesses already in advanced stages of planning and investment, especially when the municipality was aware of these plans, a "duty of consideration" (hairyo gimu) arises.

This duty demands more than procedural formality; it requires substantive engagement, a genuine effort to find solutions that might accommodate both public interests (like water source protection) and the business's existing position, and a commitment to avoid causing undue harm without thorough exploration of alternatives and appropriate guidance. The ruling provides a crucial measure of protection for businesses against abrupt and unaccommodating regulatory shifts by local authorities, reinforcing the principles of fairness and considered administrative action in the application of new local laws.