Navigating Liability for Wrongful Provisional Orders in Japan: A Supreme Court Perspective

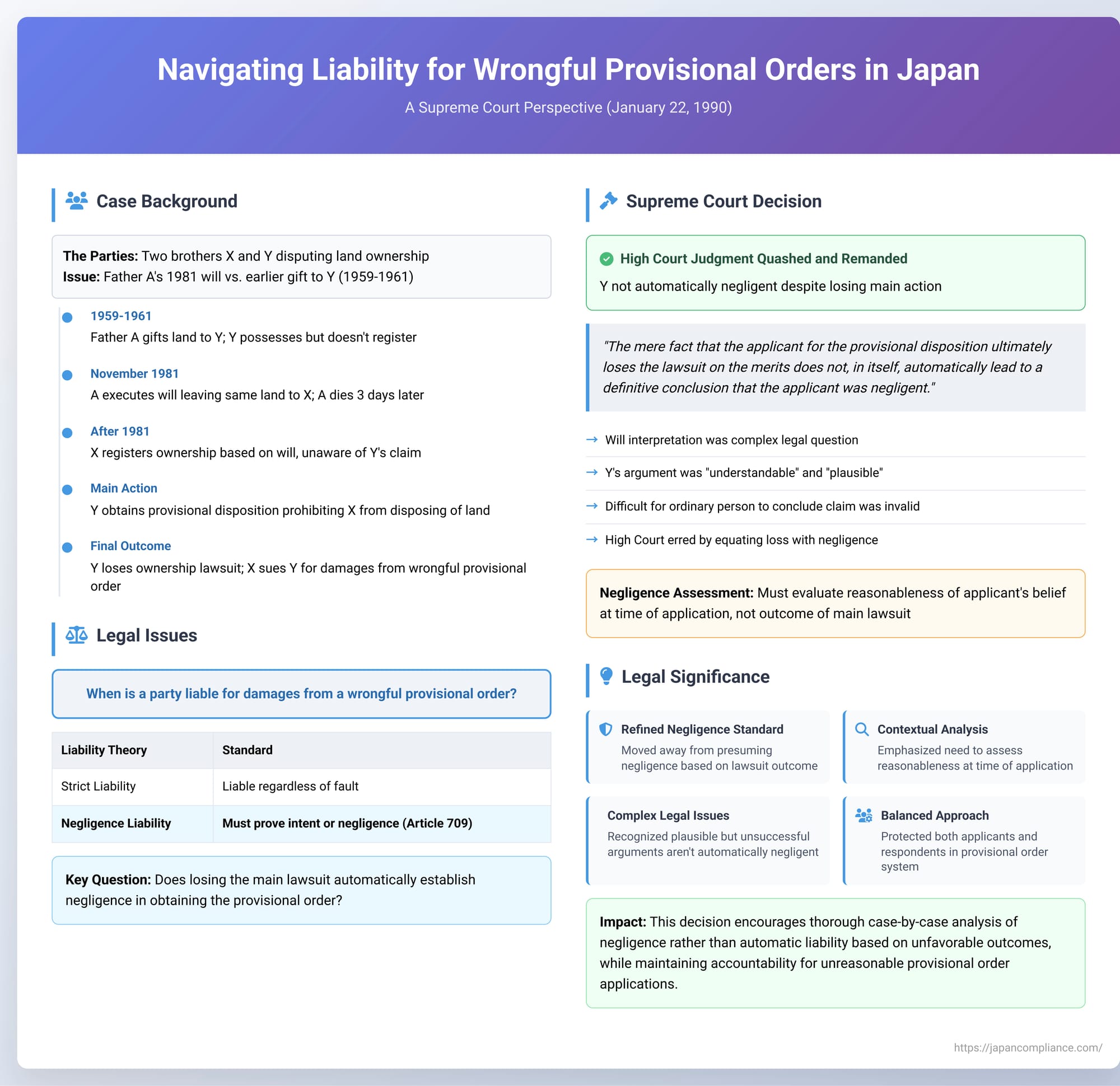

Case: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of January 22, 1990 (Case No. 1989 (O) No. 1546, Action for Damages)

This case delves into the crucial question of when a party who obtains a provisional disposition (a temporary court order, akin to a preliminary injunction) can be held liable for damages if the basis for that order is later found to be invalid. The Japanese Supreme Court's decision provides important guidance on the standard of negligence required to establish such liability under Article 709 of the Civil Code (tort liability).

I. The Genesis of the Dispute: A Family Affair Over Land

The dispute originated between two brothers, identified here as X (the respondent in the provisional disposition, later plaintiff in the damages suit) and Y (the applicant for the provisional disposition, later defendant in the damages suit), concerning a parcel of land.

The factual background is somewhat intricate:

- The Gift: Between 1959 and 1961, the brothers' father, A, gifted the land in question to his son, Y. Y took possession of and managed the land, although he did not complete the formal registration of his ownership.

- The Will: In November 1981, shortly before his death, A executed a notarized will. This will stipulated that the same parcel of land was to be "inherited" by his other son, X. A passed away just three days after making this will.

- X's Registration: Unaware of the will's contents, X was not informed by Y. X subsequently used the will as documentary proof of inheritance to apply for and obtain an ownership preservation registration for the land in his own name.

- Y's Counter-Move: The Provisional Disposition: Y, believing his claim to the land based on the earlier gift was superior, took legal action. He argued that X, by "inheriting" from A, also inherited A's pre-existing obligation to transfer the land's title to Y (stemming from the gift). Consequently, Y contended that X could not assert his inheritance-based ownership claim against Y's prior (albeit unregistered) gifted right.

Based on this, Y applied for and was granted a provisional disposition order. This order prohibited X from selling, mortgaging, leasing, or otherwise disposing of the land. The provisional disposition was duly registered.

II. The Main Action: Who Truly Owned the Land?

The provisional disposition was, by its nature, a temporary measure pending a full determination of the parties' rights in a "lawsuit on the merits" (hon'an soshō). Y initiated this main action to establish his ownership.

- Y's Arguments in the Main Action:

- Primarily, Y reiterated that X had inherited A's obligation to complete the transfer of title to Y.

- As an alternative argument, Y claimed that even if X and Y were in a position where their competing claims required registration to determine priority, X was a "bad faith party acting perfidiously" (haishinteki akuisha). Y asserted that X knew Y had received the land as a gift and had been possessing and managing it for years. Therefore, X should not be permitted to exploit Y's lack of formal registration.

- Rulings of the Lower Courts (District and High Court) in the Main Action:

Both the District Court and the High Court ruled against Y. A key turning point in these proceedings was an apparent "admission" (jihaku) by Y's side that the true intent of A's will was to make a "testamentary gift" (izō) of the land to X, rather than X acquiring it through general inheritance (sōzoku).

This distinction was critical. Under Japanese property law (specifically Article 177 of the Civil Code), if X received the land via a testamentary gift, he could be considered a "third party" in relation to the earlier, unregistered gift transaction between A and Y. As a registered third party, X's claim would generally take precedence over Y's unregistered claim. Thus, the courts found Y could not assert his ownership against X. - Supreme Court's Ruling in the Main Action:

Y appealed the High Court's decision in the main action to the Supreme Court. However, the Supreme Court upheld the lower courts' rulings, finalizing Y's loss in the land ownership dispute. - Consequences for the Provisional Disposition:

Following the final judgment in the main action, Y withdrew his application for the provisional disposition, and its registration was cancelled.

III. The Aftermath: X Sues Y for Damages

With the ownership issue settled in his favor, X turned the tables and initiated a new lawsuit against Y. This was an action for damages based on Article 709 of the Civil Code (tort).

- X's Claim: X alleged that Y had been negligent in applying for and executing the provisional disposition order.

- Alleged Damages: X claimed that the provisional disposition, by prohibiting him from dealing with the land, had prevented him from leasing it out. He sought compensation for the lost rental income during the period the order was in effect.

- Lower Courts' Rulings in the Damages Lawsuit:

Both the Nagoya District Court and the Nagoya High Court ruled in favor of X, finding that Y had indeed been negligent in pursuing the provisional disposition. They ordered Y to pay damages. It was this judgment that Y appealed to the Supreme Court, leading to the decision discussed here.

IV. The Supreme Court's Judgment in the Damages Lawsuit (January 22, 1990)

The Supreme Court's decision in this damages lawsuit is pivotal for understanding liability for wrongfully obtained provisional orders.

- A. Operative Part (Shubun – The Court's Order):

- The judgment of the Nagoya High Court (which had found Y liable for damages) was quashed (overturned).

- The case was remanded (sent back) to the Nagoya High Court for further trial and examination (shinri).

- B. Reasons (Riyū – The Court's Reasoning):

- General Principle of Liability for Wrongful Provisional Dispositions:

The Court began by restating the general legal principle: If the "right to be preserved" (hihozen kenri) by a provisional disposition order did not actually exist from the outset, the applicant who obtained and executed that order is liable for damages suffered by the respondent (the person against whom the order was directed) if the applicant acted with intent (koi) or negligence (kashitsu). This liability arises under Article 709 of the Civil Code.Crucially, the Court reiterated a point from a previous Supreme Court judgment (December 24, 1968): The mere fact that the applicant for the provisional disposition ultimately loses the lawsuit on the merits does not, in itself, automatically lead to a definitive conclusion that the applicant was negligent. - Application to Y's Case:

The Court then scrutinized the specific circumstances of Y's application for the provisional disposition:- Y's Contentions Recalled: The Court noted Y's consistent claims: he had received the land as a gift from their father, A; he had possessed and managed it; A then made a will stating X would "inherit" the land; X registered ownership without informing Y. Y had argued that X either inherited A's obligation to transfer title or was a bad-faith party.

- The Will's Interpretation: A central issue in the main action had been the interpretation of A's will – was it a "testamentary gift" (izō) to X, or was it a "designation of the method of division of inherited property" (isan bunkatsu hōhō no shitei)?

- In the main action, the lower courts had proceeded on the basis (due to the "admission") that it was a testamentary gift. This interpretation was detrimental to Y because, as an unregistered donee, he could not prevail against X, who was treated as a registered legatee (a third party).

- However, Y had appealed the High Court's decision in the main action, specifically arguing that the will should be interpreted as a "designation of the method of division of inherited property." Under this alternative interpretation, the property would pass directly to the designated heir (X) as part of the inheritance settlement, but Y argued that X, as an heir standing in A's shoes, could not assert rights against Y, to whom A had already gifted the property before A's death. This argument by Y was dismissed by the Supreme Court in the main action appeal as primarily relating to fact-finding, which is the domain of the lower courts.

- The Supreme Court's Assessment of Y's Potential Negligence in the Damages Suit:

The Court found Y's position regarding the will's interpretation to be significant:- The question of whether the will intended a "testamentary gift" or a "designation of the method of division of inherited property" is fundamentally a matter of legal interpretation of the will's wording and intent.

- The Supreme Court stated that Y's argument that the will should be interpreted as a "designation of the method of division of inherited property" was "understandable" or "plausible" (shukō shiuru tokoro de ari).

- Given the factual history as asserted by Y (the gift, his long possession, etc.), the Court further opined that, at the time Y applied for the provisional disposition, it would have been "difficult to expect an ordinary person" (tsūjōjin ni kitai suru koto mo konnan de atta) in Y's position to definitively conclude that his claim to ownership could not be asserted against X.

- Conclusion on Negligence and Remand:

Based on this analysis, the Supreme Court concluded:- The Nagoya High Court (in the damages lawsuit) had erred in law. It had found Y negligent essentially for two reasons: (1) Y had lost the main action concerning the land's ownership, and (2) Y's arguments made when applying for the provisional disposition were ultimately not accepted in the judgment of the main action.

- This approach by the High Court, the Supreme Court said, amounted to either a misinterpretation and misapplication of Article 709 of the Civil Code (regarding negligence) or an incomplete/insufficient examination of the facts and circumstances (shinri fusoku).

- This error clearly affected the outcome of the High Court's judgment in the damages suit.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court found Y's appeal on this point to be meritorious. The High Court's judgment was quashed, and the case was sent back to the Nagoya High Court for a re-examination, specifically on the issue of Y's alleged negligence, taking into account the Supreme Court's reasoning.

- General Principle of Liability for Wrongful Provisional Dispositions:

V. Analysis and Broader Implications

This Supreme Court judgment offers significant insights into how Japanese law approaches liability for provisional remedies that turn out to be unjustified.

- A. The Bedrock: Negligence Liability, Not Strict LiabilityIn many legal systems, there's a debate about the standard of liability for obtaining a provisional remedy that later proves unwarranted. Should the applicant be liable only if they were negligent (negligence liability), or should they be liable for any damages caused, regardless of fault (strict liability or no-fault liability)?The Japanese Supreme Court has consistently adhered to the negligence liability theory for wrongful provisional dispositions. This 1990 judgment explicitly reaffirms this position, citing its own 1968 precedent. Scholarly commentary notes that even during legislative discussions for the current Civil Provisional Remedies Act (Minji Hozen Hō), proposals to introduce special strict liability rules were not adopted. This legislative inaction reinforces the application of general tort principles (i.e., negligence) to these situations.

- Negligence Liability (kashitsu sekinin setsu): This is the general principle for torts under Article 709 of the Japanese Civil Code. The claimant must prove that the defendant acted with intent or negligence.

- Strict Liability (mukashitsu sekinin setsu): Proponents of strict liability in this context argue that provisional remedies are granted quickly, often ex parte or with limited opportunity for the respondent to be heard. This speed benefits the applicant but carries risks for the respondent. Thus, fairness might suggest holding the applicant strictly liable if the remedy is ultimately shown to be groundless. Analogies are sometimes drawn to liability for damages caused by provisionally enforced judgments that are later overturned.

- B. The Evolving Standard for Determining NegligenceWhile the principle is negligence, the critical question is how negligence is assessed, especially when the primary evidence of the "wrongfulness" of the provisional order is the applicant's subsequent loss in the main lawsuit.

- Earlier Approach – A Hint of Presumed Negligence?

The 1968 Supreme Court judgment, referenced in the current case, had stated that if the right sought to be preserved by the provisional disposition is found not to exist, negligence on the part of the applicant would be presumed "unless special circumstances (tokudan no jijō) exist" or if the applicant had "reasonable grounds" (sōtō na jiyū) for their application.

This "presumption" was generally understood not as a formal reversal of the burden of proof in the substantive law, but rather as a practical approach to fact-finding. It signaled that losing the main action was a strong indicator of negligence, and the applicant might then need to actively demonstrate why they were not, in fact, negligent. This approach aimed to balance the protection of the respondent with the overarching principle of negligence.

A subsequent 1982 Supreme Court decision (also dealing with a wrongful provisional disposition) found that if the applicant had "understandable reasons" for seeking the order, this could rebut the presumption of negligence. - The Refinement in the 1990 Judgment (This Case):

The current judgment appears to refine this stance subtly but significantly. Instead of speaking of a presumption to be rebutted, it states more directly: losing the main action does not, by that fact alone, immediately lead to a finding of negligence.

The emphasis shifts to a more holistic, case-by-case evaluation of whether the applicant's belief in their claim and their decision to seek provisional relief were reasonable at the time of the application, given the information available and the legal landscape as it then appeared.The Court’s reasoning that Y's interpretation of the will was "understandable" is key. It implies that even if a legal argument is novel, complex, or ultimately unsuccessful, it doesn't automatically render the applicant negligent if there was a plausible basis for it. The fact that the interpretation of A's will (as a "designation of the method of division of inherited property") advocated by Y was a legal theory that the very same Second Petty Bench of the Supreme Court would later endorse and establish as a leading interpretation in a famous 1991 case (the "Kagawa ruling," concerning specific assets "to be inherited by" a particular heir) strongly suggests that Y's claim was far from frivolous or obviously unfounded at the time. While the 1990 judgment doesn't explicitly mention this future alignment, the plausibility of Y's legal argument was clearly a decisive factor.This judgment suggests a reluctance to infer negligence too readily from the mere fact of losing the main case, especially where the underlying legal issues are complex or involve unsettled points of law. The focus is on the objective reasonableness of the applicant's conduct in light of the circumstances then prevailing.

- Earlier Approach – A Hint of Presumed Negligence?

- C. Factors Considered in Assessing Negligence:

Based on this and related case law, factors relevant to assessing an applicant's negligence might include:- The clarity (or lack thereof) of the law applicable to the applicant's claim.

- The factual basis for the claim and the efforts made to verify it.

- The complexity of the legal and factual issues involved.

- Whether the applicant's interpretation of the law and facts was tenable or reasonable at the time, even if ultimately proven incorrect.

- The urgency of the need for provisional relief and whether less intrusive means were available.

- The potential harm to the respondent versus the potential harm to the applicant if the order was not granted.

- D. Practical Implications for Litigants:

- For Applicants: While not facing strict liability, applicants for provisional remedies must still exercise significant due diligence. A thorough pre-application assessment of the merits of the underlying claim, the genuine necessity for such a potent remedy, and the potential harm to the respondent is crucial. Losing the main action will inevitably trigger scrutiny, and the applicant must be prepared to demonstrate the reasonableness of their actions at the time they sought the provisional order.

- For Respondents: If a provisional order is obtained and later proven unjustified, this judgment confirms that a claim for damages is possible, but negligence on the part of the applicant must be established. The mere fact that the order was overturned is not enough.

VI. Conclusion

The Supreme Court's January 22, 1990 judgment provides a nuanced framework for assessing liability in cases of wrongful provisional dispositions. It reinforces Japan's adherence to a negligence-based standard but cautions against equating a loss in the main action with automatic negligence.

The decision champions a more thorough inquiry into the circumstances surrounding the application for the provisional order, particularly the reasonableness and plausibility of the applicant's claims and legal interpretations as they appeared at the time of application. It reflects a careful balancing act: ensuring that provisional remedies remain effective tools for litigants who genuinely need them, while also protecting respondents from carelessly or unreasonably sought orders that can inflict significant harm. This case underscores the importance of careful legal judgment and factual investigation before resorting to the powerful mechanism of provisional court orders.