Trade Secret Protection in Japan: Practical Guide for U.S. Businesses (2025)

Learn how Japan’s Unfair Competition Prevention Act defines and protects trade secrets, and the practical steps U.S. businesses must take to secure confidential know‑how in the Japanese market.

TL;DR

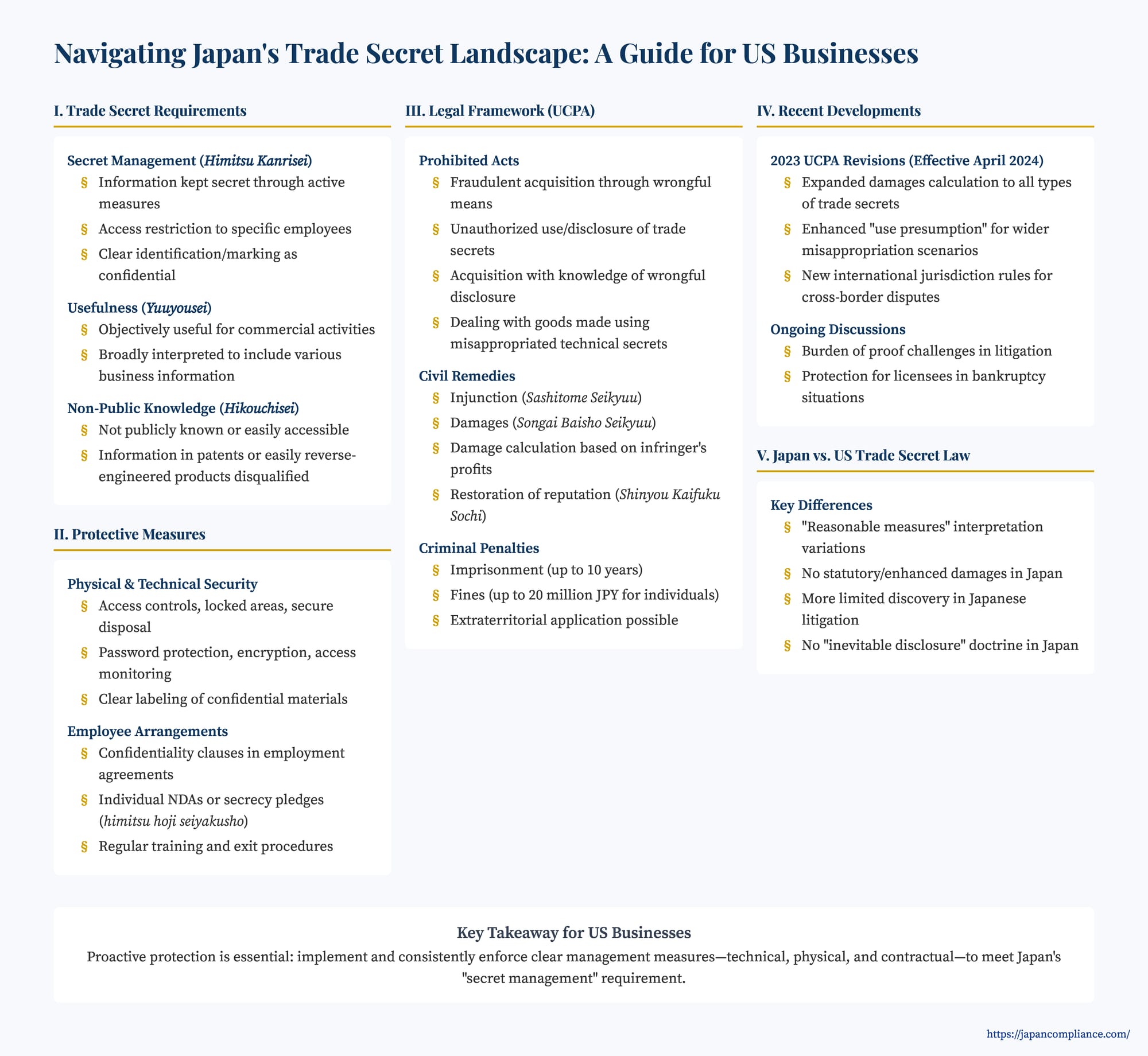

Japan’s Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA) gives strong civil and criminal remedies for trade‑secret misappropriation, but only if the owner proves: (1) active secret management, (2) commercial usefulness, and (3) non‑public knowledge. U.S. companies can mitigate risk by combining robust technical, physical and contractual controls with METI’s Trade‑Secret Management Guidelines. Recent 2023 amendments expanded damage presumptions and cross‑border reach, yet proof hurdles remain higher than in the U.S. Proactive governance is therefore essential.

Table of Contents

- What Qualifies as a "Trade Secret" Under Japanese Law?

- Implementing Effective Protective Measures: Practical Steps

- The Legal Framework: Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA)

- Recent Developments and Ongoing Discussions

- Comparing Japanese and US Trade Secret Law

- Conclusion: Proactive Protection is Key

Japan, a global hub for innovation and technology, presents significant opportunities for US businesses. However, operating in this sophisticated market requires a keen understanding of how to protect one of the most valuable assets: trade secrets. Information such as customer lists, manufacturing processes, formulas, and strategic plans often fall under this category. Losing control of such information can lead to severe competitive disadvantages.

Japan provides robust legal protection for trade secrets primarily through its Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA, 不正競争防止法 - Fusei Kyoso Boshi Ho). Understanding this framework, its requirements, and practical protective measures is crucial for any US company engaging in business activities involving Japan. This guide offers an overview tailored for US legal and business professionals.

What Qualifies as a "Trade Secret" Under Japanese Law?

Unlike patents or trademarks, trade secrets don't require registration. Protection arises automatically if the information meets three specific criteria defined in Article 2, Paragraph 6 of the UCPA. All three must be satisfied:

- Secret Management (秘密管理性 - Himitsu Kanrisei): The information must be kept secret through active management measures. This is often the most crucial and litigated requirement. The holder must demonstrate a clear intention to keep the information confidential and have implemented reasonable measures to do so. This doesn't necessarily mean Fort Knox-level security, but rather measures appropriate to the circumstances. Courts and the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) guidelines consider factors like the company's size, the nature of the information, and employee roles.

- Access Restriction: Is access to the information limited to specific employees or departments on a need-to-know basis? Physical measures (locked cabinets, restricted areas) and technical measures (passwords, encryption, access logs) are relevant.

- Clear Identification/Marking: Can those who access the information reasonably perceive it as confidential? This is often achieved by marking documents or files as "Confidential," "社外秘" (Shagai Hi - External Confidential), or similar labels. Storing information in designated secure locations or databases also helps. Simply storing information on a company server accessible to many employees without specific markings or access controls is generally insufficient.

- Usefulness (有用性 - Yuuyousei): The information must be objectively useful for commercial activities, such as production methods, sales strategies, or other business operations. This requirement is interpreted broadly. As long as the information is not harmful to public order or morals (like information on tax evasion), and possesses some objective value contributing to business activities (e.g., saving costs, improving efficiency, aiding R&D), it generally meets this criterion. Customer lists, supplier details, manufacturing know-how, experimental data, and even failed research data (as it helps avoid repeating mistakes) can qualify.

- Non-Public Knowledge (非公知性 - Hikouchisei): The information must not be publicly known or easily accessible to the general public or competitors. Information contained in publicly available patents, publications, websites, or products that can be easily reverse-engineered typically lacks non-public knowledge. Even if information is known within a specific industry, if it's not accessible outside the company without improper means, it can still be considered non-publicly known. Information published on the dark web may not necessarily lose its non-public status immediately, depending on accessibility.

Implementing Effective Protective Measures: Practical Steps

Meeting the "secret management" requirement is paramount. METI provides "Trade Secret Management Guidelines" (営業秘密管理指針 - Eigyou Himitsu Kanri Shishin), which, while not legally binding, offer valuable insights into expected standards. US companies should consider these practical steps:

- Identify and Categorize: Clearly identify what information constitutes a trade secret within the company. Not all confidential information qualifies. Categorize secrets based on sensitivity to apply appropriate levels of protection.

- Physical Security: Implement physical access controls for areas where trade secrets are stored or used (e.g., key cards, locked rooms/cabinets). Securely dispose of physical documents containing trade secrets (e.g., shredding).

- Technical Security: Use robust IT security measures, including password protection, encryption, access controls based on roles/permissions, firewalls, intrusion detection systems, and regular security audits. Monitor access logs. Control the use of removable media (USB drives).

- Marking: Clearly label documents and digital files containing trade secrets as "Confidential," "Trade Secret," or similar designations recognizable to employees.

- Employee Agreements and Training:

- Include robust confidentiality clauses in employment agreements and work rules (就業規則 - shuugyou kisoku) that explicitly cover trade secrets, define obligations during and after employment, and specify return/deletion requirements upon termination.

- Obtain individual non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) or secrecy pledges (秘密保持誓約書 - himitsu hoji seiyakusho) from employees, especially those handling sensitive information.

- Conduct regular training for all employees (including temporary staff and contractors) on the importance of trade secrets, company policies, and the legal consequences of misappropriation. Training should clarify what information is considered secret and how it should be handled.

- Third-Party Agreements: Ensure strong NDAs are in place with suppliers, contractors, joint venture partners, and any other third parties who may access trade secrets. These agreements should clearly define the scope of confidential information, permitted use, security obligations, and procedures upon contract termination.

- Exit Procedures: Implement thorough procedures for departing employees, including reminding them of confidentiality obligations, ensuring the return of all company property and information (physical and digital), and disabling access to company systems and data.

The Legal Framework: Unfair Competition Prevention Act (UCPA)

The UCPA provides the primary legal basis for protecting trade secrets and taking action against misappropriation.

Types of Prohibited Acts (Article 2, Paragraph 1, Items 4-10):

The UCPA defines several categories of acts related to trade secrets as "unfair competition." These include:

- Fraudulent Acquisition (Item 4): Obtaining a trade secret through theft, fraud, duress, or other wrongful means (不正取得 - fusei shutoku).

- Use/Disclosure after Fraudulent Acquisition (Item 5): Using or disclosing a trade secret acquired through wrongful means.

- Acquisition with Knowledge/Gross Negligence (Item 6): Acquiring a trade secret while knowing, or being grossly negligent in not knowing, that it was wrongfully acquired or disclosed previously.

- Use/Disclosure by Authorized Persons (Item 7): Disclosing a trade secret, learned legitimately from the owner (e.g., by an employee or business partner), for the purpose of unfair competition or causing harm to the owner, or using it outside the authorized scope.

- Acquisition by Subsequent Recipient (Item 8): Acquiring a trade secret while knowing, or being grossly negligent in not knowing, that it was wrongfully disclosed (under Item 7) or that there had been a prior wrongful disclosure.

- Use/Disclosure by Subsequent Recipient (Item 9): Using or disclosing a trade secret acquired under the circumstances described in Item 8.

- Assignment, Delivery, Display, Export/Import of Infringing Goods (Item 10): Dealing with goods created through the infringing use of a technical trade secret (e.g., a manufacturing process), while knowing the secret was misappropriated.

Civil Remedies:

Companies whose trade secrets have been misappropriated can seek civil remedies under the UCPA:

- Injunction (差止請求 - Sashitome Seikyuu) (Article 3): The court can order the cessation or prevention of the infringing act. This can include prohibiting the use or disclosure of the secret, or stopping the sale of products made using the secret. Destruction of infringing products or removal of equipment used for infringement may also be ordered.

- Damages (損害賠償請求 - Songai Baisho Seikyuu) (Article 4): The injured party can claim monetary damages. Proving the exact amount of damage caused by trade secret misappropriation can be difficult. Therefore, Article 5 of the UCPA provides several presumptions to assist plaintiffs in calculating damages:

- Based on Infringer's Profits (Art. 5, Para. 2): The profit gained by the infringer through the misappropriation is presumed to be the amount of damage suffered by the trade secret holder. This is often used but requires access to the infringer's financial data.

- Based on Lost Profits (Art. 5, Para. 1): For technical trade secrets, damages can be calculated based on the number of infringing products sold multiplied by the trade secret holder's profit per unit, subject to deductions based on the holder's capacity to sell. (The 2023 revision expanded this to cover non-technical secrets and services, see below).

- Based on Reasonable Royalty (Art. 5, Para. 3): Damages can be claimed equivalent to the amount the holder would have been entitled to receive as a reasonable royalty for the use of the trade secret. (The 2023 revision allows consideration of hypothetical negotiation terms, see below).

- Measures to Restore Reputation (信用回復措置 - Shinyou Kaifuku Sochi) (Article 14): The court can order the infringer to take measures necessary to restore the business reputation of the trade secret holder, such as publishing an apology.

Criminal Penalties (Article 21):

Certain severe acts of trade secret misappropriation, particularly those involving fraudulent acquisition or disclosure for unfair gain or causing harm, are subject to criminal penalties. These can include imprisonment (up to 10 years) and/or fines (up to 20 million JPY for individuals, potentially higher for corporations under dual liability provisions). The UCPA also has provisions for extraterritorial application, allowing prosecution even if parts of the crime occur outside Japan, provided the secret belongs to a business operating in Japan.

Recent Developments and Ongoing Discussions

The legal landscape surrounding trade secrets in Japan continues to evolve.

- 2023 UCPA Revisions (Effective April 2024): Significant amendments aimed at strengthening protection in the digital and global era were enacted. Key changes related to trade secrets include:

- Expansion of Damages Calculation (Art. 5): The presumption based on lost profits (Art. 5, Para. 1) was expanded beyond technical secrets to cover all types of trade secrets and situations where the infringer provides services using the secret, not just goods. The reasonable royalty calculation (Art. 5, Para. 3) was clarified to allow courts to consider the amount that would likely have been agreed upon in a hypothetical negotiation assuming the infringement occurred (mirroring 2019 patent law changes).

- Expansion of Use Presumption (Art. 5-2): A provision that presumes "use" of a technical secret if certain conditions are met (wrongful acquisition + subsequent production of related goods/services) was expanded. Previously limited to specific types of wrongful acquisition, it now potentially applies to a wider range of misappropriation scenarios, including certain cases where the secret was initially obtained legitimately but later misused with culpable knowledge (falling under Art. 2(1) Items 7 & 9). This aims to alleviate the plaintiff's burden of proving the defendant's actual use of the secret.

- International Jurisdiction Rules (New Arts. 19-2, 19-3): New provisions clarify international jurisdiction for cross-border trade secret cases and the scope of Japanese law application, aiming to provide more predictability for international disputes.

- Burden of Proof Issues: Despite the 2023 revisions, proving infringement remains a significant hurdle for plaintiffs. Evidence often resides within the defendant's control, making it difficult to access. While procedures like court orders for document submission exist (UCPA Art. 7), their effectiveness is debated. Ongoing discussions focus on further alleviating the plaintiff's evidentiary burden, potentially through broader application of presumptions or exploring systems similar to expert inspection (like the one introduced for patent law).

- Protection for Licensees: Unlike patent and copyright law, the UCPA currently lacks specific provisions protecting licensees of trade secrets or limitedly provided data if the licensor goes bankrupt or transfers the secret/business to a third party. This uncertainty can hinder data and know-how licensing. Discussions are underway to potentially introduce protective measures, possibly through recognizing a licensee's right as being enforceable against third parties ("obviously enforceable right") or creating specific exceptions to infringement liability for legitimate licensees.

Comparing Japanese and US Trade Secret Law

While sharing the common goal of protecting valuable confidential business information, Japanese and US trade secret laws differ in certain aspects:

- Definition - "Reasonable Measures": Both systems require protective measures. Japan's "secret management" (秘密管理性) focuses on the holder's intent being clear to those accessing the information (e.g., employees) through access controls and identification. The US standard of "reasonable measures under the circumstances" (under DTSA and UTSA) might be seen as slightly more flexible, but both require proactive steps.

- Statutory Damages/Enhanced Damages: The US Defend Trade Secrets Act (DTSA) allows for exemplary damages (up to double the actual damages) for willful and malicious misappropriation and attorney's fees in certain cases. Japanese law (UCPA) does not currently provide for punitive or enhanced statutory damages beyond the compensatory calculation methods (including reasonable royalty). Damage awards in Japan have historically been perceived as lower than in the US, although the 2023 UCPA revisions aim to facilitate higher damage calculations.

- Discovery: Discovery processes are generally more limited in Japan compared to the extensive discovery available in US litigation. While document production orders exist in Japan, obtaining internal documents from the opposing party can be more challenging.

- Inevitable Disclosure Doctrine: The US concept of the "inevitable disclosure" doctrine (where an employee moving to a competitor might be enjoined from working in a similar role if they would inevitably use the former employer's trade secrets) is not recognized in Japan. Preventing former employees from working for competitors relies more heavily on enforceable non-compete agreements (which are subject to strict reasonableness tests) and proving actual or threatened misappropriation.

Conclusion: Proactive Protection is Key

Japan offers a solid legal framework for protecting trade secrets through the Unfair Competition Prevention Act. However, protection hinges critically on the owner actively managing the information as secret. US companies operating in Japan must proactively implement and consistently enforce clear management measures—technical, physical, and contractual—to meet the "secret management" requirement. Staying informed about ongoing legal developments, particularly regarding damages and licensee protection, is also advisable. By understanding the specific requirements of Japanese law and taking diligent steps to safeguard their confidential information, US businesses can more effectively mitigate risks and leverage their valuable intellectual assets in the Japanese market.

- Licensing Trade Secrets and Data in Japan: Navigating the Risks to Licensee Rights

- Protecting Your IP in Japan: Strategies for Patents, Trademarks, and Copyright

- What Is Japanese Digital Business Law, and How Will Evolving Tech Like P2P and AI Reshape It?

- Unfair Competition Prevention Act – Overview (METI English)

- Management Guidelines for Trade Secrets (PDF, METI)

- Guidelines on Shared Data with Limited Access (PDF, METI)