Navigating Japan's Personal Information Protection: The My Number System and Beyond

TL;DR

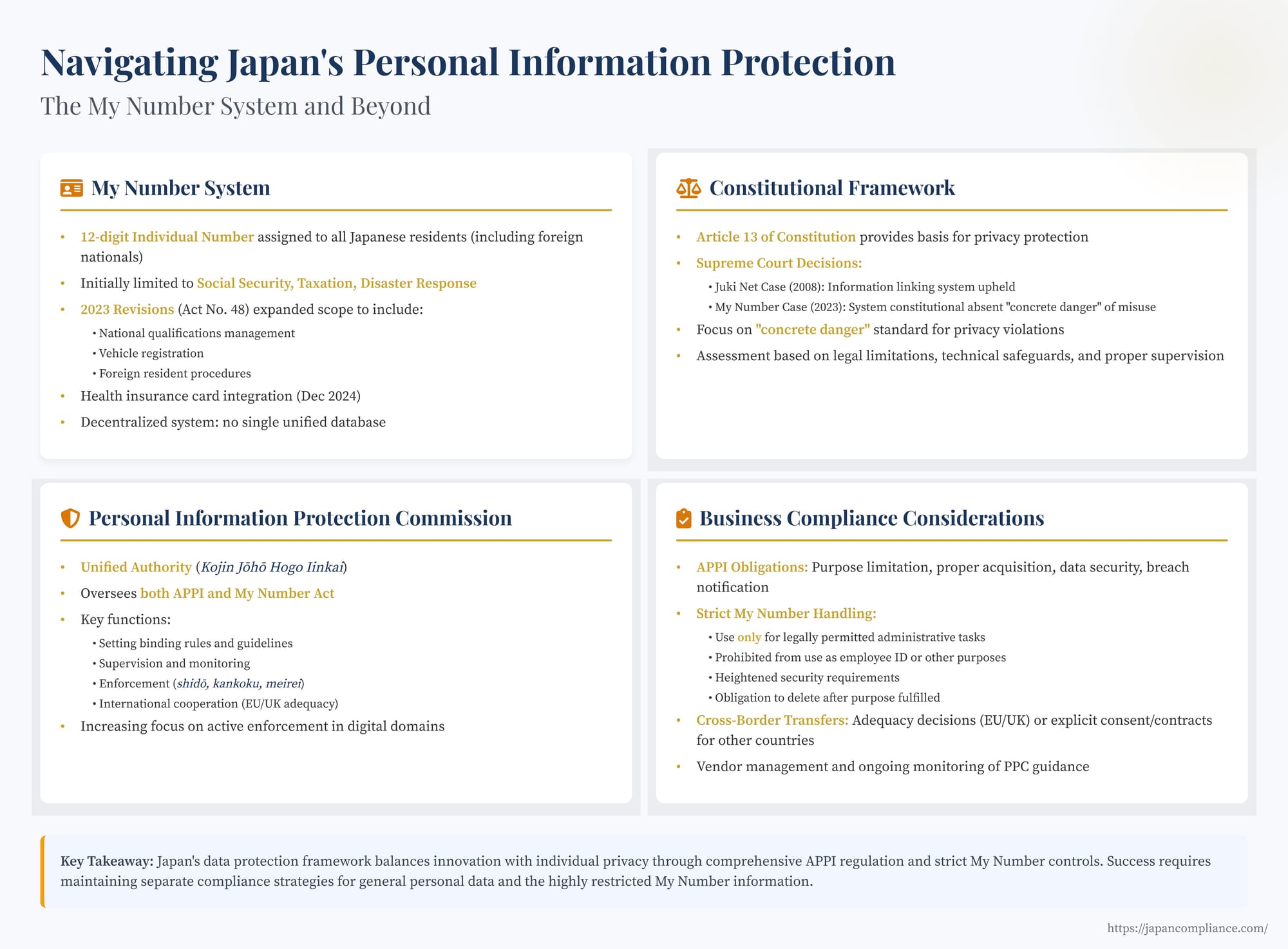

- Japan’s personal-data regime rests on the broad APPI and the strictly limited My Number Act, both enforced by the powerful Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC).

- 2023 reforms expand My Number use beyond tax/social-security into licences, vehicle registration and health-insurance integration—under tight purpose-limitation rules.

- Two Supreme Court rulings uphold these systems, provided no “concrete danger” of misuse exists. Businesses must segregate My-Number handling, follow APPI cross-border rules and track PPC guidance.

Table of Contents

- The My Number System: Structure and Recent Expansion

- Constitutional Framework: Privacy and Data Handling

- The Role of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC)

- Key Compliance Considerations for Businesses

- Conclusion

In today's digitally interconnected world, data protection has become a paramount concern for businesses operating globally. Japan, with its advanced economy and significant digital infrastructure, is no exception. Navigating the country's data protection landscape requires understanding two key pillars: the comprehensive Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) and the specific, highly regulated Act on the Use of Numbers to Identify Specific Individuals in Administrative Procedures, commonly known as the My Number Act. Both frameworks operate under the increasingly watchful eye of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC), Japan's unified data protection authority. For US companies doing business in or with Japan, a clear grasp of these regulations, recent reforms, and their constitutional underpinnings is essential for compliance and risk management.

The My Number System: Structure and Recent Expansion

The My Number system (マイナンバー制度 - Mai Nanbā Seido), introduced via the My Number Act (Act No. 27 of 2013), assigns a unique 12-digit "Individual Number" (個人番号 - kojin bangō, or "My Number") to every resident of Japan, including foreign nationals. Its initial purpose was strictly limited to streamlining administrative procedures in three core areas: Social Security, Taxation, and Disaster Response. The system aimed to improve efficiency, ensure fairness in benefits and burdens, and enhance convenience for citizens by allowing various government agencies to link necessary information accurately for specific, legally defined administrative tasks.

Crucially, the system was designed with privacy safeguards in mind from the outset. It does not create a single, centralized government database containing all personal information linked to the My Number. Instead, information remains dispersed across the agencies that originally collected it for their specific purposes. Linkage between agencies for permitted tasks occurs via a secure, dedicated Information Provision Network System, which uses derived codes, not the My Number itself, for matching.

In June 2023, the Diet enacted significant revisions to the My Number Act (Act No. 48 of 2023), signaling a shift towards broader utilization of the system to further accelerate Japan's digital transformation. Key changes include:

- Expanded Scope of Use: While maintaining the principle that new uses must be explicitly defined by law, the Act's basic philosophy now embraces promoting My Number utilization in "other administrative affairs" beyond the original three fields. The 2023 revisions specifically added several new areas, such as administrative procedures related to:

- National qualifications (e.g., for barbers/beauticians, architects, small vessel operators).

- Vehicle registration.

- Residency status applications for foreign nationals.

- Streamlined Linkage Mechanisms:

- "Quasi-Statutory Affairs" (準法定事務 - Jun Hōtei Jimu): The law now allows My Number to be used for administrative tasks deemed "equivalent in nature" to those listed explicitly, if defined by ministerial ordinance. This provides some flexibility for extending usage to similar processes without immediate legislative action, although the scope of "equivalence" will be critical.

- Information Linkage via Ordinance: For administrative tasks already legally authorized to use My Number, the necessary data sharing (information linkage - 情報連携 jōhō renkei) between government bodies can now often be enabled through ministerial ordinances, streamlining the process compared to requiring specific legal amendments for each linkage path.

- Integration with Health Insurance: The revisions mandate the phasing out of separate health insurance cards (from December 2, 2024) and their integration with the My Number Card, which contains an IC chip. Individuals will use the card for online eligibility verification at medical providers.

- Other Enhancements: The revisions also included adding phonetic readings (furigana) to names in official records and on the card, and simplifying the registration of bank accounts for receiving public benefits.

These reforms aim to position the My Number and the associated My Number Card as a core piece of digital identity infrastructure for accessing a wider range of public services efficiently.

Constitutional Framework: Privacy and Data Handling

The handling of personal information by the state, particularly through comprehensive systems like My Number, inevitably raises constitutional questions regarding privacy. In Japan, the relevant provision is Article 13 of the Constitution, which guarantees the right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, and states that these rights shall, "to the extent that it does not interfere with the public welfare, be the supreme consideration in legislation and in other governmental affairs." The Supreme Court of Japan has long interpreted Article 13 as protecting the privacy of individuals.

Two key Supreme Court rulings provide crucial context for understanding the constitutional limits on government handling of personal identification data:

- The Juki Net Decision (March 6, 2008): This case challenged the constitutionality of the Basic Resident Registration Network (住民基本台帳ネットワーク - Jūmin Kihon Daichō Nettowāku or "Juki Net"), an earlier system linking basic resident information (name, address, date of birth, gender, and a resident code) across municipalities. The plaintiffs argued the system violated their right to privacy under Article 13. The Supreme Court acknowledged that Article 13 protects the "freedom...not to have information concerning one's private life arbitrarily disclosed to third parties." However, it found the Juki Net system constitutional. The Court reasoned that the information handled (the four basic items plus the code) was not highly sensitive, its use was limited by law to specific administrative purposes, and the system incorporated technical and legal safeguards against leaks and misuse. Crucially, the Court found no "concrete danger" that the information would be unlawfully disclosed or misused beyond its intended administrative scope.

- The My Number Decision (March 9, 2023): Plaintiffs across Japan challenged the My Number Act, arguing that the collection, storage, use, and linkage of Specific Personal Information (特定個人情報 - tokutei kojin jōhō, defined as personal information containing the My Number) under the system violated their Article 13 privacy rights, particularly the freedom from arbitrary collection and utilization of personal information, and posed an unacceptable risk of data breaches and misuse.The Supreme Court, reaffirming the Juki Net precedent, again focused on the "concrete danger" standard. It reiterated that Article 13 protects the freedom from arbitrary disclosure or publication of personal information. The Court analyzed the My Number system's structure and safeguards:Based on these factors, the Supreme Court concluded that, under the legal framework as it stood then, the My Number system did not present a "concrete danger" that Specific Personal Information would be collected, stored, used, or provided beyond the legally permitted scope, nor that it would be improperly disclosed or published. Therefore, the Court held that the system did not violate the Article 13 right to privacy.

- Strict Purpose Limitation: The My Number Act explicitly limits the collection, use, and provision of My Number and Specific Personal Information to the legally defined purposes (Social Security, Tax, Disaster Response at the time).

- Decentralized Management: Data remains stored by the respective agencies; there is no single unified database.

- Information Linkage Mechanism: The Information Provision Network System uses different codes, not the My Number itself, for data matching, reducing linkage risks.

- Legal and Technical Safeguards: The Act includes numerous provisions for safe management, restrictions on handling, supervision by the PPC, and penalties for misuse or leaks.

The significance of these rulings lies in the standard applied: the mere collection and use of personal identification data by the government is not per se unconstitutional. The crucial question is whether the specific legal and technical framework creates a concrete risk of improper access, disclosure, or misuse beyond legitimate administrative purposes. While the My Number system was upheld, the 2023 ruling implicitly leaves open the possibility that future legislative changes (like the subsequent 2023 revisions expanding its scope), systemic failures, or inadequate security measures could potentially alter this risk assessment.

The Role of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC)

As Japan digitizes its administration and expands data utilization, the role of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC - 個人情報保護委員会 - Kojin Jōhō Hogo Iinkai) has become central. Initially established in 2014 (as the Specific Personal Information Protection Commission) to oversee the My Number system, its mandate was significantly broadened in 2016 to cover the APPI for the private sector. Following the major 2020 and 2021 amendments to the APPI, which unified previously separate data protection laws for the private sector, national government, and independent administrative agencies, the PPC became the single, powerful independent authority overseeing personal information protection across both the public and private sectors nationwide (local government rules were also aligned with the APPI standard, though direct supervision often remains with local authorities, coordinated with the PPC).

The PPC's key functions include:

- Setting Rules and Guidelines: Issuing legally binding rules and detailed guidelines interpreting the APPI and the My Number Act. These guidelines (e.g., 通則編 - General Rules, 外国にある第三者への提供編 - Provision to Third Parties in Foreign Countries) are essential references for compliance.

- Supervision and Monitoring: Overseeing compliance by businesses and administrative organs, including requesting reports and conducting on-site inspections.

- Enforcement: Issuing guidance (指導 - shidō), recommendations (勧告 - kankoku), and administrative orders (命令 - meirei) to rectify violations. Non-compliance with orders can lead to penalties. Recent enforcement actions have targeted issues like inadequate security measures leading to data breaches, improper handling of sensitive data, and failures in vendor supervision.

- International Cooperation: Engaging with foreign data protection authorities and playing a key role in establishing and maintaining frameworks for international data transfers, such as the adequacy decisions with the European Union and the United Kingdom. This includes overseeing the application of the "Supplementary Rules" (補完的ルール - hokanteki rūru) applicable to data transferred from the EU/UK under these decisions, which impose stricter handling requirements for certain data categories.

- Policy Guidance: Developing the government's "Basic Policy" on personal information protection and publishing "Basic Principles" to guide administrative agencies in designing policies involving personal data handling.

The PPC's unified authority and expanding activities underscore the Japanese government's commitment to robust data protection enforcement in the digital age. Businesses must pay close attention to PPC guidance and enforcement trends.

Key Compliance Considerations for Businesses

For US companies operating in Japan, compliance involves understanding obligations under both the general APPI and the specific My Number Act.

1. Core APPI Obligations

The APPI applies to nearly all businesses handling personal information in Japan. Key obligations include:

- Purpose Specification and Limitation: Clearly specify the purpose of use when collecting personal information and generally use it only within that scope.

- Proper Acquisition: Do not acquire personal information through deceit or other improper means. Notify individuals of the purpose of use upon acquisition (unless already publicly announced).

- Sensitive Information (要配慮個人情報 - yō-hairyō kojin jōhō): Obtain explicit prior consent before collecting sensitive data, which includes race, creed, social status, medical history, criminal record, and information indicating one has been a victim of crime, etc. (The Supplementary Rules for EU/UK data add sexual life, sexual orientation, and labor union membership to this category for transferred data).

- Data Security Management (安全管理措置 - anzen kanri sochi): Implement necessary and appropriate technical, organizational, and physical measures to prevent leaks, loss, or damage of personal data.

- Supervision of Employees and Vendors (委託先の監督 - itaku-saki no kantoku): Exercise necessary and appropriate supervision over employees handling personal data and over third-party vendors entrusted with data processing. Vendor due diligence and contractual clauses are critical.

- Data Breach Notification: In case of certain types of data breaches (e.g., involving sensitive information, risk of property damage, involving over 1,000 records), promptly notify the PPC and affected individuals.

- Third-Party Provision: Generally requires prior consent to provide personal data to third parties, with some exceptions (e.g., outsourcing, statutory requirement). An "opt-out" mechanism is available for non-sensitive data under specific conditions, but it's generally not applicable to data transferred under the EU/UK adequacy decision. Stricter rules apply for transfers to third parties located outside Japan.

- Data Subject Rights: Respond appropriately to requests from individuals for disclosure, correction, deletion, or cessation of use of their retained personal data.

2. Handling My Number (Specific Personal Information)

Handling My Number or data containing it (Specific Personal Information - tokutei kojin jōhō) is subject to much stricter rules under the My Number Act than general personal information under the APPI.

- Extreme Purpose Limitation: Businesses can only collect and use My Number for administrative procedures explicitly stipulated by law, primarily related to social insurance filings, tax withholding procedures (e.g., preparing gensen-chōshū-hyō tax summaries for employees), and legally mandated disaster response coordination. Using My Number for any other purpose (e.g., as a general employee ID, for marketing, for credit checks) is strictly prohibited, even with the individual's consent.

- Collection Restrictions: Businesses can only request My Number when necessary for legally permitted administrative tasks.

- Prohibition on Creating Databases: Businesses generally cannot create databases compiling My Numbers beyond what is strictly necessary for the legally defined administrative tasks.

- Heightened Security Measures: Specific and robust security measures are required for storing and handling Specific Personal Information.

- Deletion Obligation: Specific Personal Information must be deleted promptly once the legally mandated administrative purpose for which it was collected is fulfilled.

Non-compliance with the My Number Act carries significant penalties. Businesses must treat My Number handling with extreme care and limit its scope strictly to legally required administrative processes.

3. Cross-Border Data Transfers

Transferring personal data from Japan to locations outside the country (including back to a US headquarters) is regulated under the APPI. Key mechanisms include:

- Adequacy Decisions: Transfers to countries recognized by the PPC as having an equivalent level of data protection (currently the EU/EEA and the UK) are permitted relatively freely, subject to compliance with the aforementioned Supplementary Rules for data originating from those regions.

- Other Mechanisms: For transfers to other countries (like the US, which lacks a general adequacy decision from Japan), businesses typically need to rely on:

- The individual's explicit consent to the transfer abroad (requiring specific information disclosure).

- Contractual agreements between the data exporter and importer ensuring the importer upholds APPI-equivalent standards.

- Certification under an international framework recognized by the PPC (e.g., APEC Cross-Border Privacy Rules - CBPR system).

- Establishing binding corporate rules (equivalent) recognized by the PPC for intra-group transfers.

Businesses must carefully assess the appropriate legal basis and implement necessary safeguards for any cross-border transfer of personal data originating from Japan.

Navigating the Evolving Landscape

The data protection landscape in Japan is dynamic. The unification of rules under the APPI and the PPC's consolidated authority aim for consistency, but businesses still face complexities:

- Keeping Updated: The PPC regularly issues new guidelines and Q&As. Staying informed about these interpretations is crucial for compliance.

- Managing My Number Risk: The severe restrictions and penalties associated with My Number misuse require dedicated compliance efforts, distinct from general APPI compliance.

- Vendor Management: Ensuring third-party vendors, especially cloud service providers or data processors located overseas, meet Japan's data protection standards requires rigorous due diligence and contractual oversight.

- Global Consistency: Multinational companies need to reconcile Japan's specific requirements (especially regarding My Number and the Supplementary Rules for EU/UK data) with other global data protection regimes like GDPR or CCPA/CPRA.

Conclusion

Japan has established a robust and evolving framework for personal information protection, centered on the comprehensive APPI and the highly specific My Number Act, all under the supervision of the increasingly active Personal Information Protection Commission. The recent digital reforms, particularly the expansion of the My Number system's scope, underscore the government's direction while simultaneously highlighting the critical need for stringent privacy safeguards. For US businesses, successful operation in Japan demands a thorough understanding of these distinct but interconnected regulations, diligent implementation of compliance measures (especially the strict limitations on My Number use), and ongoing attention to guidance from the PPC. Proactive data governance and a commitment to respecting individual privacy rights are essential components of sustainable business practice in Japan's digital future.

- Navigating Japan’s Digital Transformation: Key Legal Reforms Shaping the Business Landscape

- Five Years On: GDPR Enforcement Trends, Record Fines & the EDPB’s Growing Power

- AI Training Data and Copyright in Japan: Understanding Article 30-4 Exceptions

- Personal Information Protection Commission – APPI & My Number Guidelines (Japanese)

- Digital Agency – My Number Card & Online Verification Info (Japanese)