Japan’s New Security-Clearance System: Guide for Foreign Firms

TL;DR: Japan will launch a security-clearance system by 2026 allowing access to “Specified Secret Information” in economic-security projects. Foreign subsidiaries can apply but must appoint vetted liaison officers, localise data storage and accept intrusive background checks. Early preparation is critical, especially for dual-use tech and critical-infrastructure contracts.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Key Features of Japan’s Security-Clearance Framework

- Eligibility, Scope and Classification Levels

- Application Procedures and Timelines

- Implications for Foreign Businesses and Joint Ventures

- Compliance Strategies and Best Practices

- Conclusion

Introduction: Economic Security Takes Center Stage in Japan

In recent years, "economic security" has rapidly ascended the policy agenda in Japan, mirroring global trends where economic tools are increasingly intertwined with national security objectives. Against a backdrop of escalating geopolitical tensions, supply chain vulnerabilities, and intensifying competition over critical and emerging technologies, Japan has been actively strengthening its legislative framework to safeguard its national interests.

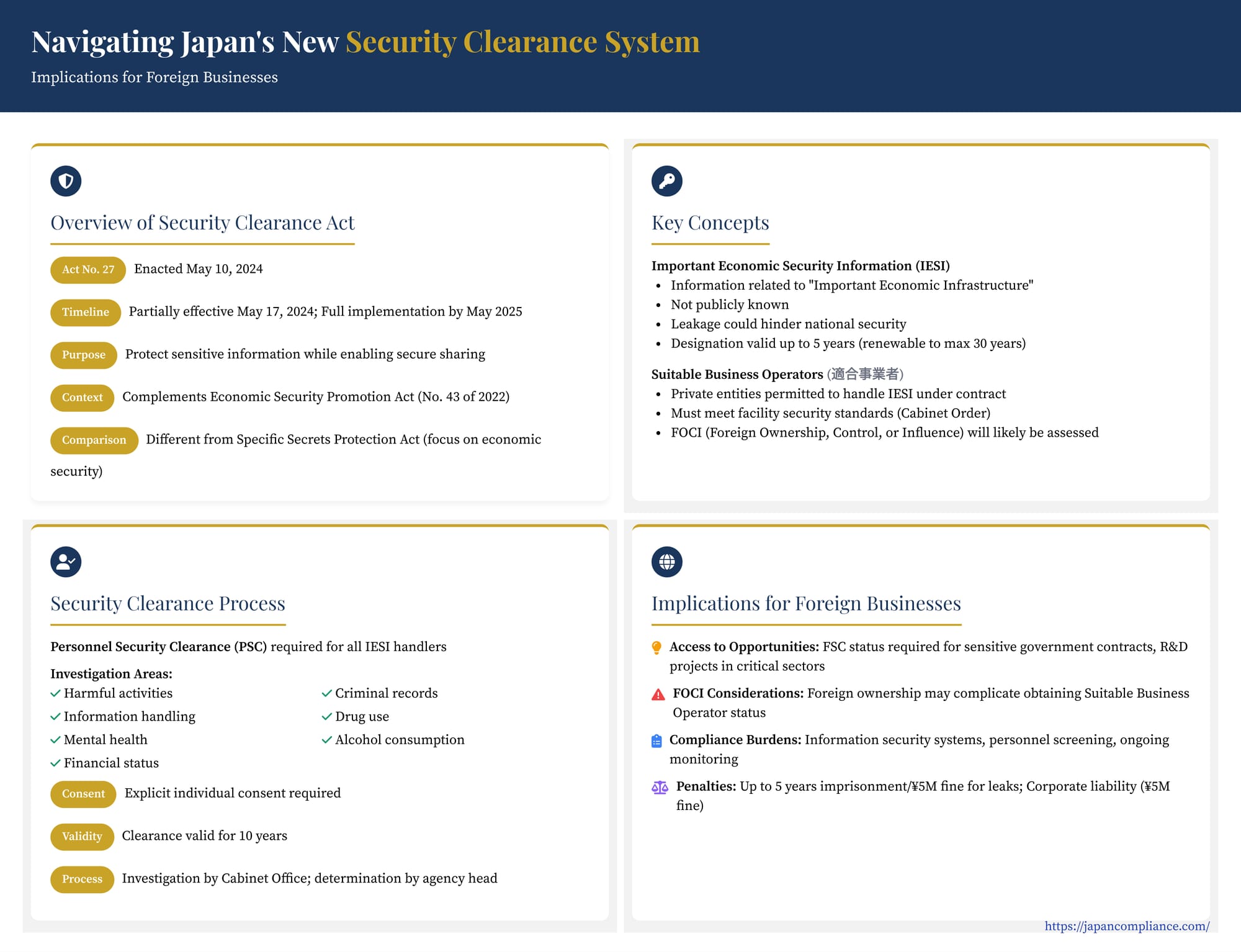

A cornerstone of this effort is the Act on the Protection and Utilization of Important Economic Security Information (Act No. 27 of 2024), enacted on May 10, 2024, and partially effective from May 17, 2024, with full implementation expected within approximately one year. This landmark legislation introduces a formal security clearance system, often referred to as "SC," designed to protect sensitive information crucial to Japan's economic foundations while enabling its secure sharing with trusted private sector partners.

This development follows the enactment of the Economic Security Promotion Act (Act No. 43 of 2022), which laid the groundwork by establishing frameworks for securing critical supply chains, ensuring the reliability of core infrastructure, supporting advanced technology development, and creating a patent secrecy system. The new security clearance law complements these measures by addressing the vital need for robust information security protocols, particularly as Japan seeks deeper collaboration with allies like the United States and participates in international joint research and development involving sensitive technologies.

For foreign businesses operating in or collaborating with Japan, particularly in sectors deemed critical, understanding this new security clearance regime is paramount. It has significant implications for accessing certain government contracts, participating in sensitive projects, managing personnel, and potentially structuring corporate operations within Japan.

Overview of the New Security Clearance Act

The Act establishes a comprehensive system for handling sensitive economic security information, built upon three core pillars:

- Designation of Information: The government designates specific information related to Japan's "important economic infrastructure" as "Important Economic Security Information" (IESI) if its leakage could potentially harm national security.

- Strict Handling Rules: It mandates rigorous protocols for managing, accessing, and sharing designated IESI. This includes the implementation of a security clearance system for individuals ("Personnel Security Clearance" - PSC) and criteria for businesses ("Facility Security Clearance" - FSC, through designation as "Suitable Business Operators").

- Penalties: It introduces criminal penalties for unauthorized disclosure (leaks) or acquisition of IESI.

This structure broadly aligns with information protection regimes in other major countries, aiming to build international trust in Japan's capacity to safeguard sensitive data, thereby facilitating information sharing with foreign partners.

Relationship with Existing Secrecy Laws

Japan already has the Act on the Protection of Specially Designated Secrets (Act No. 108 of 2013), commonly known as the Specific Secrets Protection Act (SSPA). The SSPA protects information whose leakage poses a "grave threat" (著しい支障) to national security, primarily in defense, diplomacy, counter-intelligence, and counter-terrorism. This corresponds roughly to higher classification levels like "Top Secret" or "Secret" in the U.S. system.

The new Act targets information deemed sensitive for economic security, where leakage poses a risk of "hindrance" (支障) – a lower threshold than the SSPA. This is often compared to the U.S. "Confidential" level. Information classified as a "Specially Designated Secret" under the SSPA is explicitly excluded from designation as IESI under the new Act (Art. 3(1)).

A key distinction highlighted by the government is the new Act's emphasis on utilization alongside protection (Article 1). While the SSPA focuses primarily on restricting access to highly sensitive secrets, the new Act aims to facilitate the secure sharing of IESI with trusted private sector entities to promote activities beneficial to national security, such as strengthening critical infrastructure or supply chains.

Key Concepts: IESI and Suitable Business Operators

What is "Important Economic Security Information" (IESI)?

Article 3(1) of the Act empowers the heads of relevant administrative agencies to designate information as IESI if it meets the following criteria:

- It falls under the agency's jurisdiction and constitutes "Important Economic Infrastructure Protection Information" (重要経済基盤保護情報).

- It is not publicly known.

- Its leakage could potentially hinder Japan's national security, making specific secrecy necessary.

"Important Economic Infrastructure" (重要経済基盤) is defined in Article 2(3) and broadly refers to Japan's critical infrastructure and critical goods supply chains. This concept is wider than the specific infrastructure and goods designated under the 2022 Economic Security Promotion Act.

"Important Economic Infrastructure Protection Information" (Article 2(4)) pertains to this infrastructure and includes information concerning:

* Measures (including plans or research) to protect the infrastructure from external threats (e.g., details of government response plans to cyberattacks on critical infrastructure operators).

* Vulnerabilities, innovative technologies, or other critical details related to the infrastructure that have national security implications (e.g., information on supply chain weak points susceptible to external disruption).

* Information received from foreign governments or international organizations regarding protection measures.

* Intelligence gathering and analysis capabilities related to the above.

Specific examples and further details are expected in the operational standards (運用基準) to be established by Cabinet decision. Crucially, information already in the public domain cannot be designated.

Designation, Validity, and Declassification

The designation of IESI is made by the head of the administrative agency holding the information. This implies that information held solely by private companies, without government involvement, is not subject to designation under this Act. However, information originally from the private sector but subsequently provided to and held by a government agency can be designated. Even if such information is designated, the original private holder is not automatically subject to the Act's obligations unless they receive or hold the IESI under a specific contract based on Article 10.

Designations have a validity period of up to 5 years, renewable potentially up to 30 years. Extensions beyond 30 years require Cabinet approval, and the total period generally cannot exceed 60 years (with exceptions for human intelligence sources, etc.) (Article 4). Designation ceases upon expiry of the validity period or if the agency head formally cancels the designation because the information no longer meets the criteria (Article 4(7)). Oversight mechanisms, including verification by the Independent Inspector-General for Archives Management, are planned to ensure appropriate designation and declassification.

"Suitable Business Operators" (適合事業者)

A key mechanism for sharing IESI with the private sector involves identifying "Suitable Business Operators" (適合事業者). Article 10(1) allows an agency head holding IESI to provide it to a business operator under contract if necessary to promote activities contributing to national security (e.g., resolving infrastructure vulnerabilities, R&D).

To qualify, the operator must meet standards set by Cabinet Order, including having necessary facilities and equipment for information protection. These standards, currently under development, are expected to address aspects of corporate suitability, potentially including considerations related to Foreign Ownership, Control, or Influence (FOCI). The government's expert panel report referenced FOCI analysis in the U.S. system, suggesting that Japan's framework will likely consider similar factors, balancing the need for international collaboration with security risks. The specific criteria and how FOCI assessments will be conducted will be critical details for foreign-affiliated companies.

Importantly, the sharing of IESI is based on a contract (e.g., a non-disclosure agreement) between the government agency and the Suitable Business Operator. This means the operator must consent to receive the information and undertake the associated obligations. Businesses cannot be forced to accept IESI and the accompanying regulatory burdens against their will. Once a Suitable Business Operator receives IESI under contract, it must manage the information strictly according to regulations and ensure that only personnel with the appropriate security clearance handle it.

The Security Clearance Process

The Act establishes a system for vetting individuals who will handle IESI.

Who Needs Clearance?

Personnel Security Clearance (PSC) is required for anyone handling IESI, except for certain high-ranking officials like Ministers of State (Article 11(1)). This includes:

* Government employees.

* Employees (including representatives, agents, and other personnel) of Suitable Business Operators contracted to handle IESI.

The Evaluation Process (適性評価)

The core of the PSC is the "suitability assessment" (適性評価, tekisei hyōka).

- Consent: The assessment cannot be conducted without the individual's explicit consent (Article 12(3)). This consent must be genuine, free from coercion by the employer. Mechanisms like government complaint channels are planned to ensure this.

- Eligibility: Only individuals expected to perform duties requiring access to IESI are eligible for assessment (Article 12(1)). It is not a general background check available upon request.

- Investigation Scope: The assessment involves an investigation covering seven specific areas (Article 12(2)):

- Connections to activities harmful to important economic infrastructure (e.g., espionage, terrorism).

- Criminal and disciplinary records.

- History of mishandling sensitive information.

- Drug abuse and influence.

- Mental health conditions potentially affecting judgment or reliability.

- Issues related to alcohol consumption (moderation).

- Credit status and other financial circumstances.

- Centralized Investigation: While the final determination of suitability rests with the administrative agency head responsible for the information (or contracting with the Suitable Business Operator), the investigation itself will generally be conducted centrally by the Cabinet Office, upon request from the agency head (Article 12(4)-(6)). The Cabinet Office provides the results and an opinion back to the requesting agency. The investigation can involve interviews with the subject and related persons, requests for documents, and inquiries to public or private entities.

- Portability: An assessment result finding an individual suitable ("no risk of leakage") is generally valid for 10 years (Article 11(1)). To avoid redundant checks, if an individual cleared by one agency needs access to another agency's IESI within 10 years, the second agency can generally rely on the existing Cabinet Office investigation results to make its own suitability determination (Article 12(7)).

- Relationship with SSPA Clearance: Individuals already holding a valid clearance under the SSPA (within the last 5 years from the same agency head) are deemed suitable to handle IESI without needing a new assessment under this Act (Article 11(2)), reflecting the higher sensitivity level assessed under the SSPA.

Notification and Appeals

The individual is notified of the assessment result ("no risk of leakage" or otherwise). If working for a Suitable Business Operator, the operator is also notified of the outcome (but not the sensitive details gathered during the investigation) (Article 13). If found unsuitable, the individual is notified of the reason, within limits that do not compromise the assessment process (Article 13(4)). Individuals can file a complaint regarding the assessment process or outcome with the relevant agency head, who must handle it sincerely and notify the complainant of the result (Article 14).

Purpose Limitation on Use of Assessment Results

Crucially, Article 16 prohibits both government agencies and Suitable Business Operators from using or providing the assessment results for any purpose other than the protection of IESI. This means that an employer (Suitable Business Operator) cannot use an employee's refusal to undergo assessment, or an unsuitable finding, as a basis for general performance reviews, unrelated personnel decisions, or other disadvantageous treatment beyond restricting access to IESI-related work. This is a vital safeguard for employee rights.

Implications for Foreign Businesses

The introduction of Japan's SC system presents both opportunities and challenges for foreign companies.

- Access to Opportunities: Possessing FSC status (as a Suitable Business Operator) and having personnel with PSC will likely become prerequisites for participating in certain sensitive government procurements, national R&D projects, and collaborations within critical sectors like defense, space, cybersecurity, and advanced technologies. Companies equipped to meet these requirements may gain a competitive advantage.

- Compliance Burdens: Achieving and maintaining FSC and PSC status involves costs and administrative effort. Companies will need robust internal information security systems, personnel screening protocols (respecting consent and privacy), and ongoing compliance monitoring.

- FOCI Considerations: As mentioned, the criteria for Suitable Business Operators are expected to include FOCI assessments. Foreign ownership, control structures, or significant ties to certain foreign governments could potentially complicate or preclude designation as a Suitable Business Operator, thereby limiting access to IESI and related projects. The specific thresholds and mitigation measures allowed will be critical details defined in upcoming regulations. U.S. companies with Japanese subsidiaries or joint ventures will need to carefully assess their corporate structures and governance in light of these potential requirements.

- Personnel Management: Companies needing employees to handle IESI must navigate the PSC process. This requires obtaining genuine employee consent for the investigation, which covers sensitive personal information. Managing foreign national employees requiring clearance may present additional complexities depending on investigation capabilities and reciprocity agreements (or lack thereof). The strict purpose limitation on using assessment results in general HR is a key protection but requires careful internal implementation.

- Supply Chain Security: The requirements may cascade down the supply chain. Prime contractors designated as Suitable Business Operators might be required to ensure their subcontractors handling sensitive aspects also meet certain security standards, potentially including elements of the SC system.

- International Alignment: While modeled on international standards, specific differences between Japan's SC system and those of the U.S. or other partners may arise. Issues of mutual recognition or interoperability of clearances will be important for seamless international collaboration.

Enforcement and Penalties

The Act introduces significant penalties for mishandling IESI, aiming to deter leaks and espionage.

- Leakage: Unauthorized disclosure of IESI by those handling it in the course of duty is punishable by imprisonment of up to 5 years, a fine of up to JPY 5 million, or both (Article 23(1)). Negligent leakage is also penalized.

- Unauthorized Acquisition: Obtaining IESI through deceptive means, violence, threats, or unauthorized access (hacking) carries penalties of up to 5 years imprisonment or a fine of up to JPY 5 million (Article 24(1)). Attempted acquisition is also punishable.

- Corporate Liability: Unlike the SSPA, the new Act includes provisions for corporate liability (両罰規定, ryōbatsu kitei) (Article 28). If an employee commits certain violations (like leakage or unauthorized acquisition) in relation to the corporation's business, the corporation itself can face fines (up to JPY 5 million for Article 23(1) or 24(1) violations), in addition to the penalties imposed on the individual employee. This underscores the need for robust corporate compliance programs.

Implementation and Next Steps

The Act is being implemented in phases. Preparatory provisions came into force on May 17, 2024. The main operative parts, including the designation of information, the suitability assessment process, and penalties, will come into effect on a date specified by Cabinet Order, which must be no later than May 16, 2025 (one year from promulgation).

Key implementing regulations, including the detailed criteria for Suitable Business Operators and the operational standards for designation and assessment, are currently under development by the government, with input from expert advisory councils. These documents, expected to be finalized potentially by the end of 2024 or early 2025, will provide crucial details for businesses seeking to understand and comply with the new regime.

Transitional measures exist (Article 2 of Supplementary Provisions), allowing certain government and police personnel to handle IESI without formal clearance for a limited period (up to one year from full implementation) if designated by their agency head. However, this grace period does not apply to private sector employees, who will require clearance from the date the main provisions take effect.

Conclusion: Preparing for a New Era of Information Security

Japan's new security clearance legislation marks a significant step in strengthening its economic security posture. It reflects a global reality where protecting sensitive technological and economic information is integral to national security. For foreign businesses engaged in Japan, particularly in technology-intensive or critical infrastructure sectors, this system introduces new compliance requirements and strategic considerations.

While the Act aims to facilitate secure information sharing for beneficial purposes, navigating the clearance processes for both facilities (FSC) and personnel (PSC), understanding FOCI implications, and ensuring robust internal controls will be essential. Companies should closely monitor the release of detailed Cabinet Orders and operational standards and begin assessing their potential exposure and preparatory needs. Proactive engagement with these requirements will be key to successfully operating within Japan's evolving economic security landscape.

- Platforms and National Security: Emerging Legal Issues in Japan

- Japan Targets Mobile Ecosystems: Inside the Smartphone Software Competition Act

- EU Battery Regulation: Global Reach—Impact on US & Japanese Supply Chains

- Cabinet Office — Draft Security-Clearance Bill Outline (JP)

https://www.cao.go.jp/keizaianzen/clearance_outline.html