Navigating Japan's New Human Rights Due Diligence Guidelines: A Guide for US Businesses

TL;DR

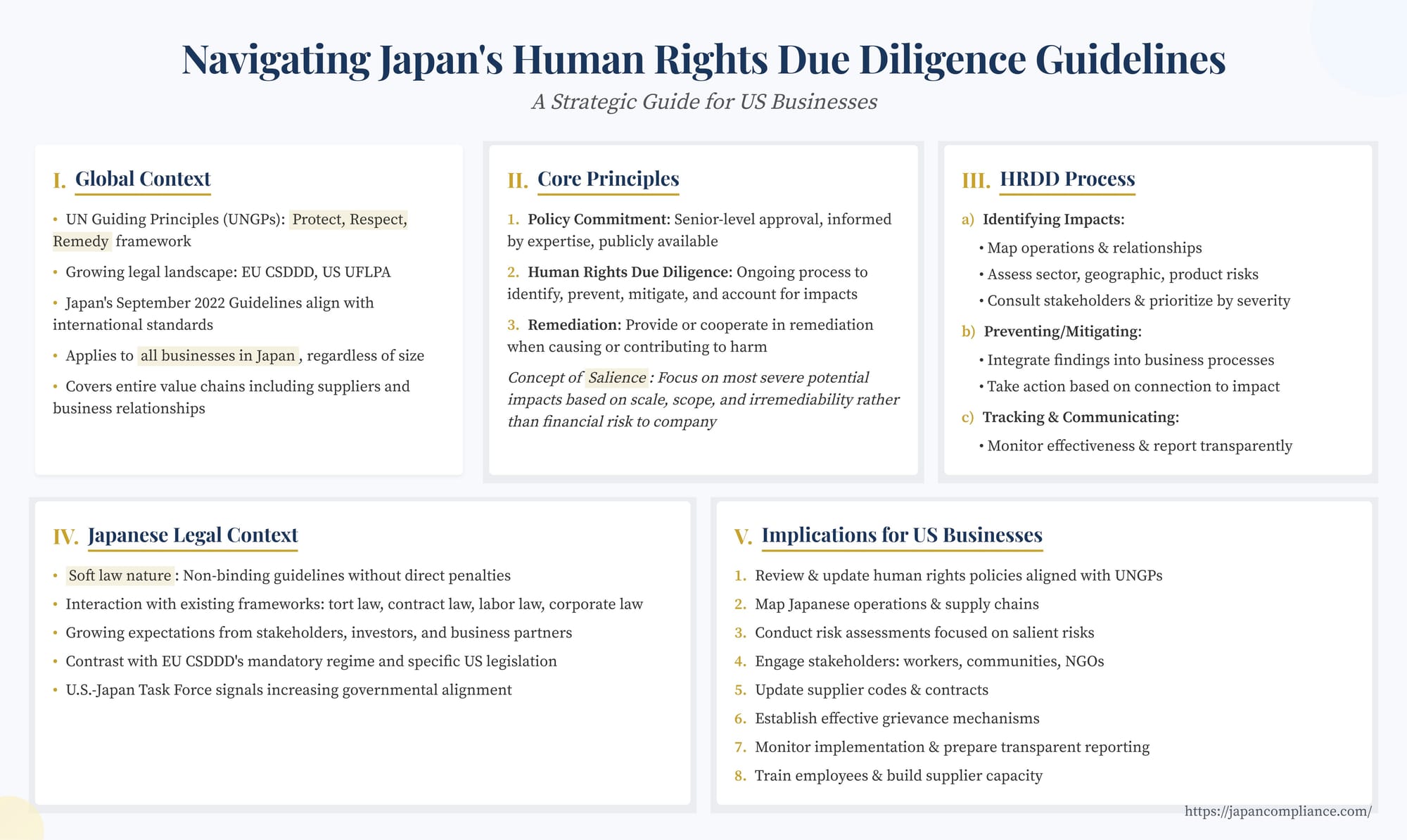

- Japan’s 2022 soft-law HRDD Guidelines align with the UNGPs and expect all firms in Japan to map, assess and address human-rights risks.

- Salience—not financial materiality—drives prioritisation; leverage over suppliers is key and abrupt disengagement should be a last resort.

- No fines yet, but investor, customer and contractual pressure plus tort and contract exposure make compliance a commercial imperative.

- US companies must update policies, map Japanese supply chains, consult stakeholders, embed clauses and create grievance channels.

Table of Contents

- The Global Rise of Business and Human Rights

- Japan's Response: The 2022 Guidelines

- Core Principles of the Japanese Guidelines

- The HRDD Process in Detail

- The Japanese Legal and Regulatory Context

- Practical Implications for US Businesses

- Conclusion

The Global Rise of Business and Human Rights

The landscape of international business is undergoing a significant transformation. Increasingly, corporations are expected not only to pursue profits but also to respect human rights throughout their operations and value chains. This heightened focus, often termed Business and Human Rights (BHR), stems from the recognition that corporate activities can have profound impacts, both positive and negative, on individuals and communities worldwide.

The foundational framework for this shift is the United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights (UNGPs), unanimously endorsed by the UN Human Rights Council in 2011. The UNGPs articulate a "Protect, Respect, and Remedy" framework: the state duty to protect human rights, the corporate responsibility to respect human rights, and the need for access to effective remedy for victims of business-related abuses. Central to the corporate responsibility to respect is the concept of human rights due diligence (HRDD) – an ongoing risk management process that companies should undertake to identify, prevent, mitigate, and account for how they address their adverse human rights impacts.

Following the UNGPs, other international bodies like the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) have elaborated on these expectations, issuing detailed guidance for multinational enterprises and specific sectors on implementing effective due diligence. This international consensus is rapidly translating into national and regional action. The European Union is advancing its Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD), mandating HRDD and environmental due diligence for large companies operating within its market, with phased implementation expected to begin from 2027. Several European nations already have national HRDD laws. In the United States, while a comprehensive federal mandate is absent, legislation like the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act (UFLPA) employs import restrictions based on a rebuttable presumption of forced labor, effectively compelling due diligence for supply chains linked to specific regions or entities.

Japan's Response: The 2022 Guidelines

Against this backdrop, Japan took a significant step in September 2022 by releasing its first government-endorsed "Guidelines on Respect for Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains" (hereafter, "the Guidelines"). Developed through multi-stakeholder consultations led by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI), the Guidelines aim to clarify expectations for companies operating in Japan and provide practical guidance on implementing HRDD.

The timing and content of the Guidelines signal Japan's intention to align with international BHR standards and address potential gaps compared to regulatory developments in the EU and US. While the Guidelines themselves are currently "soft law"—meaning they do not impose direct legal obligations or penalties for non-compliance—they represent a clear statement of government policy and expectation. They serve two primary purposes:

- International Signaling: To demonstrate to international partners, investors, and consumers that Japan takes BHR seriously and that Japanese companies are expected to adhere to global standards, thereby maintaining trust and competitiveness.

- Domestic Promotion: To raise awareness and encourage the adoption of HRDD practices among Japanese businesses, including small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), which may be less familiar with these concepts.

The Guidelines explicitly reference the UNGPs and OECD guidance as their foundation. They apply to all business enterprises conducting activities in Japan, regardless of size or sector, and extend expectations to their supply chains and other business relationships.

Core Principles of the Japanese Guidelines

The Guidelines are structured around the core pillars of the UNGPs:

- Policy Commitment: Businesses are expected to establish a formal policy expressing their commitment to respecting human rights. This policy should be approved at the most senior level, informed by relevant internal and external expertise, clearly communicate expectations to employees and business partners, and be publicly available. Many large Japanese firms have already established such policies.

- Human Rights Due Diligence (HRDD): This is the operational core of the Guidelines. It involves an ongoing process encompassing four key stages:

- Identifying and assessing actual and potential adverse human rights impacts connected to the company's operations, products, or services through its own activities or business relationships.

- Integrating findings and taking appropriate action to cease, prevent, or mitigate identified adverse impacts.

- Tracking the effectiveness of responses.

- Communicating externally how impacts are addressed.

- Remediation: Where a company identifies that it has caused or contributed to an adverse impact, it should provide for or cooperate in its remediation through legitimate processes. This involves establishing or participating in effective operational-level grievance mechanisms accessible to affected stakeholders.

A key concept emphasized is salience. Companies should prioritize addressing the most severe potential human rights impacts, determined by their scale (gravity), scope (number of individuals affected), and irremediability (difficulty in restoring victims to their previous situation). This differs from traditional corporate risk management, which often prioritizes "materiality"—the financial risk to the company. Under the HRDD framework, the focus is on the risk to people.

The HRDD Process in Detail

The Guidelines, drawing from international standards and elaborated upon by expert commentary, outline a practical approach to the HRDD process:

a) Identifying and Assessing Adverse Impacts:

This initial step requires a comprehensive understanding of the company's operational context.

- Mapping Operations and Relationships: Businesses need to map their own activities, group companies, supply chains (both upstream suppliers of goods/services and downstream distributors/consumers), and other relevant business relationships (e.g., joint venture partners, franchisees, investee companies).

- Identifying General Risk Areas: Companies should leverage publicly available resources and expert knowledge to identify general areas of human rights risk. This involves considering:

- Sector Risks: Certain industries inherently carry higher risks (e.g., apparel manufacturing - labor rights; agriculture/fishing - worker health & safety, chemical exposure; extractives - land rights, environmental impacts).

- Geographic Risks: The operating context matters significantly. Risks are often heightened in countries with weak governance, inadequate rule of law, high levels of poverty or inequality, conflict, or where specific vulnerable groups reside.

- Product/Service Risks: Some products or services may be linked to specific risks (e.g., minerals sourced from conflict zones, technology used for surveillance).

- Entity-Specific Risks: A company's own business model, governance structure, or past conduct can elevate risks.

- Assessing Specific Impacts: Based on the general risk assessment, companies must delve deeper to identify specific actual and potential impacts on specific groups of people. This requires gathering detailed information, often through:

- Supplier questionnaires (Self-Assessment Questionnaires - SAQs).

- Direct dialogue and consultation with potentially affected stakeholders (workers, communities, human rights defenders, unions, NGOs). This is crucial as the perspective of those impacted may differ significantly from the company's view. Where direct dialogue is unsafe or impractical, credible intermediaries should be used.

- Internal and external expert input.

- Site visits and audits (though recognizing their limitations).

- Prioritizing Based on Salience: Given that resources may be limited, companies must prioritize impacts based on their severity (scale, scope, irremediability), not just their likelihood or financial implications for the company.

b) Preventing and Mitigating Adverse Impacts:

Once salient risks are identified, companies must act.

- Integration: Findings from the impact assessment must be integrated into relevant company functions and processes (e.g., procurement, contracting, product design, HR).

- Action: The appropriate action depends on the company's connection to the impact:

- Causing the impact: The company must cease or prevent the activity causing the impact.

- Contributing to the impact: The company must cease or prevent its contribution and use its leverage to mitigate any remaining impact.

- Directly linked to the impact: If the company's operations, products, or services are directly linked to an impact caused by a business relationship (e.g., a supplier), the company must use its leverage to influence that entity to prevent or mitigate the impact. Leverage refers to the ability to effect change in the wrongful practices of the entity causing the harm. If leverage is insufficient, the company should seek to increase it (e.g., collaborating with other buyers or industry initiatives). As a last resort, responsible disengagement may need to be considered, weighing the potential adverse human rights consequences of ending the relationship. Suspending or terminating contracts with non-compliant suppliers is explicitly contemplated by the Guidelines framework. However, abrupt disengagement can sometimes worsen the situation for affected people (e.g., leading to job losses without remedy), so it requires careful consideration.

c) Tracking Effectiveness:

HRDD is an ongoing process. Companies need to track the effectiveness of their actions, verifying whether adverse human rights impacts are actually being addressed. This involves feedback from affected stakeholders and periodic reassessment.

d) Communicating and Reporting:

Businesses should communicate externally about their HRDD efforts, particularly when dealing with impacts that pose significant risks to human rights. Transparency is key to accountability. This includes explaining how the company identifies and addresses impacts, focusing on forward-looking information about prevention and mitigation efforts.

The Japanese Legal and Regulatory Context

Understanding the legal environment surrounding the Guidelines is crucial for US businesses.

- Soft Law Nature: As mentioned, the Guidelines themselves are not legally binding in the way a statute is. There are no direct penalties prescribed within the Guidelines for non-compliance.

- Interaction with Existing Laws: While Japan lacks a dedicated HRDD law, corporate activities are already subject to various existing legal frameworks where human rights issues can arise:

- Tort Law: Companies causing harm through negligence or intentional acts can face civil liability lawsuits. Failure to conduct adequate due diligence could potentially be argued as negligence in certain contexts.

- Contract Law: As explored in legal commentary, human rights violations in the production process (e.g., use of child labor) could potentially constitute a breach of contract or render goods non-conforming, particularly if CSR clauses or specific representations were made. The failure by a business partner to adhere to human rights standards could trigger contractual remedies, although enforcing these upstream can be challenging.

- Labor Law: Japan has extensive labor laws protecting workers' rights. Companies must ensure compliance within their own operations and should be aware of risks associated with dispatched workers or subcontractors.

- Corporate Law: Directors have a duty of care towards their company. Failing to manage salient human rights risks that lead to significant financial or reputational damage could potentially expose directors to shareholder derivative suits, although establishing this link can be difficult under current Japanese jurisprudence.

- Growing Expectations: Despite the soft law nature, expectations from investors, consumers, business partners (especially those subject to mandatory HRDD in their home countries), and civil society are rapidly increasing. Failure to demonstrate adequate HRDD could lead to:

- Divestment or difficulty securing investment.

- Loss of contracts or business opportunities.

- Consumer boycotts and reputational damage.

- Increased scrutiny from NGOs and media.

- Comparison with Hard Law Regimes: The Japanese approach currently contrasts with the mandatory, penalty-backed regimes emerging in the EU (CSDDD) and specific US legislation (UFLPA). The EU CSDDD, for instance, includes provisions for administrative supervision, fines, and civil liability. The UFLPA uses import bans based on a presumption of forced labor. While Japan's Guidelines lack such direct enforcement teeth, the practical pressures pushing companies towards compliance are substantial and growing. Collaborative efforts, like the U.S.-Japan Task Force on the Promotion of Human Rights and International Labor Standards in Supply Chains, also signal increasing governmental alignment on these issues.

Practical Implications for US Businesses

For US companies with operations, investments, or significant supply chain links in Japan, the Guidelines necessitate proactive engagement:

- Review and Update Policies: Ensure a clear, board-approved human rights policy is in place, aligned with UNGP expectations and reflecting the scope of the company's Japanese footprint.

- Map Supply Chains: Gain visibility into supply chains connected to Japanese operations. Identifying direct (Tier 1) suppliers is a starting point, but HRDD expectations extend further upstream where risks are salient.

- Conduct Risk Assessments: Systematically identify and assess potential and actual adverse human rights impacts associated with Japanese operations and supply chains, prioritizing based on salience. Pay special attention to known high-risk sectors (as identified by METI or international bodies) and geographic contexts. Consider engaging local expertise.

- Engage Stakeholders: Develop processes for meaningful consultation with potentially affected groups (workers, communities) and other relevant stakeholders (unions, NGOs) in Japan and connected supply chains.

- Integrate and Act: Embed HRDD findings into procurement practices, supplier contracts, and relevant business processes. Update supplier codes of conduct and contractual clauses to reflect human rights expectations clearly. Develop strategies for using leverage to address identified issues with business partners.

- Establish Grievance Mechanisms: Ensure accessible and effective channels are available for individuals and communities to raise concerns related to the company's impacts without fear of reprisal.

- Monitor and Report: Implement systems to track the effectiveness of mitigation measures and prepare to communicate HRDD efforts transparently, aligning with emerging international reporting standards where applicable (e.g., ISSB).

- Training and Capacity Building: Train relevant employees and management, as well as key suppliers, on the company's human rights policy and HRDD procedures.

Conclusion: Proactive Engagement is Key

Japan's 2022 Guidelines on Respect for Human Rights in Responsible Supply Chains mark a pivotal moment for businesses operating in the country. While currently soft law, they reflect a strong governmental endorsement of international BHR standards and align Japan more closely with global trends toward mandatory due diligence. The practical pressures from investors, consumers, civil society, and international regulations mean that ignoring these expectations is increasingly untenable.

For US companies, the Guidelines present both a challenge and an opportunity. They require investment in understanding and managing human rights risks within complex value chains. However, proactively embedding robust HRDD processes can not only mitigate legal, financial, and reputational risks but also enhance brand value, strengthen stakeholder relationships, build more resilient supply chains, and contribute positively to a more sustainable and equitable global economy. Understanding and navigating these Guidelines is no longer optional but a critical component of responsible business conduct in Japan.