Navigating Japan's 'Land with Unknown Owners' Crisis: New Laws and Business Implications

TL;DR: Japan’s 2021 land-reform package attacks the “unknown owners” crisis via mandatory inheritance registration, a land-reversion system, relaxed co-ownership rules, and court-appointed managers. Businesses must adapt due-diligence and compliance processes but may gain new tools to unlock stalled projects.

Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Growing Challenge of Ownerless Land

- Root Causes of the Problem

- The 2021 Legal Reforms: A Multi-pronged Approach

- Implications for Businesses

- Conclusion: Adapting to an Evolving Landscape

Introduction: The Growing Challenge of Ownerless Land

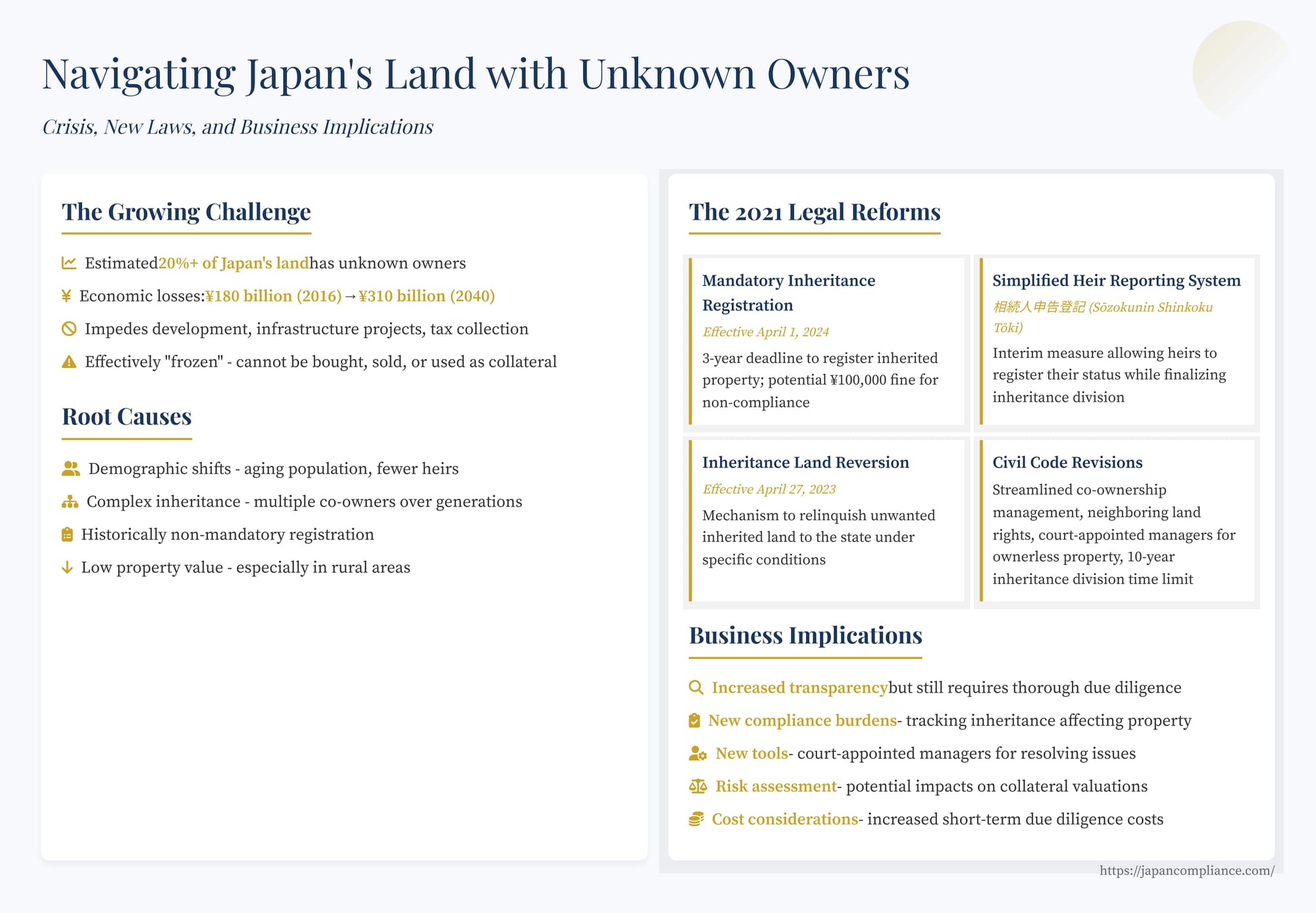

Japan is grappling with a significant and escalating issue: land with unknown owners (所有者不明土地 - shoyūsha fumei tochi). Estimates suggest that a substantial portion of land in Japan, potentially exceeding 20% and projected to grow significantly in the coming decades, falls into this category. This phenomenon, where the rightful owner of a property cannot be readily identified or located due to unrecorded inheritances piling up over generations or owners moving without updating registrations, poses considerable challenges.

This isn't merely an administrative headache; it has tangible economic consequences. Land with unknown owners becomes effectively frozen – it cannot be easily bought, sold, developed, or used as collateral. This impedes urban redevelopment, infrastructure projects, efficient land use (especially in agriculture and forestry), post-disaster recovery efforts, and the collection of property taxes. The economic losses attributed to this issue were estimated at ¥180 billion in 2016 and are projected to reach ¥310 billion annually by 2040, accumulating to a potential total loss of ¥6 trillion over that period if left unaddressed. For businesses operating or investing in Japan, particularly in real estate, construction, energy, or any sector involving land use, this presents risks of project delays, increased due diligence costs, and difficulties in site acquisition or management.

Root Causes of the Problem

Several factors contribute to the proliferation of ownerless land:

- Demographic Shifts: Japan's rapidly aging population and declining birthrate mean fewer heirs, many of whom live far from inherited rural properties they have little connection to or use for.

- Complex Inheritance: Under Japanese law, when someone dies without a will, their property is co-owned by all statutory heirs. Over generations, the number of co-owners can multiply exponentially, making consensus for sale or registration difficult.

- Lack of Mandatory Registration (Historically): Until recently, registering inheritance of real property was not legally mandatory. Many heirs, particularly for low-value rural land, avoided the registration process due to the associated costs (surveying, legal fees, registration taxes) and hassle, especially if there were numerous co-heirs to coordinate with.

- Low Property Value: In many depopulated rural areas, the market value of land is negligible or even negative when considering ongoing property taxes and management responsibilities, disincentivizing heirs from claiming or registering their inheritance.

The 2021 Legal Reforms: A Multi-pronged Approach

Recognizing the severity of the issue, the Japanese government enacted a comprehensive package of legal reforms in 2021, amending fundamental laws like the Civil Code and the Real Property Registration Act, and creating new legislation. These reforms, which came into effect in stages culminating mostly in 2023 and 2024, aim to both prevent the creation of new ownerless land and facilitate the use and management of existing ownerless properties. Key pillars include:

1. Mandatory Inheritance Registration (Effective April 1, 2024)

Perhaps the most impactful change is the introduction of mandatory registration for inherited real property. Key points include:

- Obligation: Heirs who acquire real estate through inheritance (or bequest) are now legally obligated to register the change in ownership.

- Deadline: This registration must generally be applied for within three years of the heir becoming aware of the inheritance and their acquisition of the property (Real Property Registration Act, Art. 76-2, Para. 1). This rule also applies retroactively to inheritances that occurred before April 1, 2024, with the three-year clock starting from April 1, 2024, or the date the heir became aware, whichever is later.

- Penalties: Failure to comply without a justifiable reason can result in a non-criminal administrative fine (過料 - karyō) of up to ¥100,000 (Real Property Registration Act, Art. 164, Para. 1). While the enforcement approach is expected to be initially lenient, the existence of the penalty underscores the government's commitment to compliance.

- Goal: The primary aim is preventative – to stop the accumulation of unregistered inheritances that lead to land ownership becoming obscured over time. Statistics show a significant increase in inheritance registrations since the reforms were announced and implemented, suggesting the measures are having an effect.

2. Simplified Heir Reporting Registration System (相続人申告登記 - Sōzokunin Shinkoku Tōki)

Recognizing that finalizing inheritance division among multiple heirs can take time, a simplified interim measure was also introduced (Real Property Registration Act, Art. 76-3).

- Function: An heir can meet the initial three-year deadline by making a simple declaration to the Legal Affairs Bureau, registering themselves as an heir without needing details of the final inheritance division or the consent of other heirs.

- Effect: This registration officially notifies the registry that an inheritance has occurred and lists the reporting heir's name and address. It fulfills the heir's initial registration obligation, though a further registration reflecting the final ownership structure is required once the inheritance division is settled (within three years of settlement).

- Trade-offs: While simpler, this system results in multiple heirs potentially being listed on the registry for a single property, which doesn't fully resolve ownership clarity until the final division is registered.

3. Inheritance Land Reversion to National Treasury System (相続土地国庫帰属制度 - Sōzoku Tochi Kokko Kizoku Seido) (Effective April 27, 2023)

This new system provides a mechanism for heirs to relinquish ownership of unwanted inherited land directly to the state, under specific conditions (Act on Vesting of Land Ownership Acquired through Inheritance, etc., in the National Treasury).

- Purpose: It addresses situations where land has little market value, is costly to maintain, and cannot easily be sold or donated, offering a "last resort" to prevent it from becoming abandoned or ownerless. This is distinct from general inheritance renunciation (sōzoku hōki), which requires renouncing all inherited assets, not just specific land plots.

- Strict Conditions: Land cannot be reverted if it meets certain disqualifying criteria (the "rejection requirements" - kyakka yōken), such as having buildings on it, being contaminated, having boundary disputes, being subject to mortgages or other rights, or containing accessways used by others (Act Art. 2, Para. 3).

- Further Disapproval Criteria: Even if not immediately rejected, the application can be disapproved (fushōnin) if the land requires excessive cost or effort for management or disposal, such as having hazardous cliffs, obstacles (structures, vehicles, certain types of dense vegetation like bamboo), underground objects needing removal, or potential disputes with neighbors (Act Art. 5, Para. 1).

- Financial Contribution: If the application is approved, the applicant must pay a fee equivalent to ten years' worth of standard land management costs (負担金 - futankin). The base amount is ¥200,000 per plot, but it can be calculated based on area for certain land types (like urban residential land or farmland), potentially reaching significant sums.

- Application Status: As of late 2024, thousands of applications had been filed, with a substantial number approved and reverted. Common reasons for rejection or disapproval included boundary issues, unwanted structures/vegetation, or unsuitable forest land. Interestingly, a significant portion of withdrawn applications occurred because a third party (like a neighbor or municipality) expressed interest in acquiring the land during the review process, highlighting a potential matchmaking effect.

4. Revisions to Civil Code and Related Laws

The 2021 reforms also included important updates to the Civil Code concerning property co-ownership, neighboring land rights, and inheritance division:

- Streamlined Co-ownership Management: Rules for managing co-owned property were relaxed. For instance, certain changes to co-owned property (excluding major alterations) can now be made with the consent of co-owners representing a majority of ownership shares, rather than requiring unanimous consent (Civil Code, Art. 252, Para. 1). This aims to prevent management paralysis when some co-owners are unknown or uncooperative.

- Neighboring Land Rights (Lifelines): Rules were clarified and established regarding the installation and use of essential utilities (water, gas, electricity, etc.) that need to pass through neighboring land, providing clearer rights for landowners needing such access (Civil Code, Arts. 213-2, 213-3). Rules regarding overhanging branches were also revised, allowing landowners to cut encroaching branches under certain conditions if the neighbor fails to act (Civil Code, Art. 233, Para. 3).

- New Management Systems for Owner-Unknown Property: Specific court-ordered management systems were created for individual properties (land or buildings) where the owner is unknown or their whereabouts are unknown (所有者不明土地管理人・所有者不明建物管理人 - Shoyūsha Fumei Tochi/Tatemono Kanrinin). Appointed by a district court upon petition by an interested party (like a co-owner, neighbor, or municipality), these managers can be granted authority to manage, renovate, or even sell the specific property under court supervision (Civil Code, Arts. 264-2 to 264-8). This provides a more targeted and potentially less costly alternative to the traditional, broader Absentee Property Manager system (不在者財産管理人 - fuzaisha zaisan kanrinin) overseen by family courts. Statistics show significant uptake, often for facilitating property sales.

- Inheritance Division Time Limit: A rule was introduced stating that when dividing an inherited estate more than 10 years after the inheritance commenced, the division should generally be based on statutory inheritance shares (or shares specified in a will), rather than adjusting for special contributions (kiyobun) or lifetime gifts (tokubetsu jueki) received by specific heirs (Civil Code, Art. 904-3). This aims to simplify and expedite inheritance settlements that have remained unresolved for long periods, thereby reducing the likelihood of property becoming ownerless.

Implications for Businesses

These legal changes have wide-ranging implications for companies operating or investing in Japan:

- Increased Transparency & Due Diligence: Mandatory inheritance registration should, over time, improve the accuracy and timeliness of property registries. However, in the short-to-medium term, businesses involved in real estate transactions, M&A, or infrastructure development must still conduct thorough due diligence to identify potential ownership issues stemming from past unregistered inheritances. The simplified Heir Reporting Registration may show an inheritance has occurred but not the final owner, requiring further investigation.

- New Compliance Burdens: Companies holding real estate assets in Japan need internal processes to track inheritances affecting their property (e.g., if a co-owning individual or entity head passes away) and ensure compliance with the three-year registration deadline to avoid potential fines.

- Resolving Existing Issues: The new court-appointed management systems for ownerless land/buildings offer a potentially valuable tool for businesses facing obstacles due to neighboring ownerless properties (e.g., needing consent for boundary work, redevelopment, or resolving nuisances). Petitioning for a manager might facilitate necessary actions or even acquisition.

- Land Acquisition & Development: While the ownerless land problem persists, the reforms offer pathways, albeit complex ones, to address it. Mandatory registration may make identifying heirs easier in the future. The management order system can unlock specific problematic parcels. The land reversion system, while primarily for individuals, might indirectly clear some logjams if heirs use it for adjacent low-value plots hindering a larger project (though this is not its main purpose).

- Risk Assessment: The 10-year rule for inheritance division might simplify long-unsettled estates but could also alter expected outcomes based on historical contributions or gifts, potentially impacting collateral valuations or inherited business assets if not settled promptly.

- Cost Considerations: While the aim is long-term improvement, businesses may face increased short-term costs related to enhanced due diligence, compliance procedures for registration, or potentially petitioning for court-appointed managers.

Conclusion: Adapting to an Evolving Landscape

Japan's "land with unknown owners" crisis is a complex socio-economic issue rooted in demographic trends and historical legal frameworks. The 2021 legal reforms represent a significant and multifaceted governmental effort to mitigate the problem's growth and provide tools for managing existing situations. Mandatory inheritance registration aims to prevent future issues, while the land reversion system offers a (conditional) exit route for individuals. Crucially, the revisions to co-ownership rules and the new property management systems provide potential avenues for resolving conflicts and unlocking stalled properties.

For businesses, these changes create both new obligations and potential opportunities. Enhanced transparency is the long-term goal, but navigating the transition requires heightened awareness and diligence. Understanding the new registration requirements, the scope of the land reversion system, and the potential uses of the court-ordered management systems will be essential for companies involved in Japanese real estate, development, and investment. Staying informed about the practical application and ongoing evolution of these laws will be key to successfully navigating Japan's changing property landscape.

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan: Key Differences for U.S. Investors

- Real Estate Auctions in Japan: A Primer on Commencement, Seizure and Sale Conditions

- Mortgagee's Reach: Can a Japanese Mortgage Extend to Rental Income from the Property?

- Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism — Portal on Owner-Unknown Land Measures

https://www.mlit.go.jp/totikensangyo/totikensangyo_fr5_000150.html