Navigating Japan's Evolving IP Landscape: Key Considerations for UGC, Derivative Works, and Creator Rights

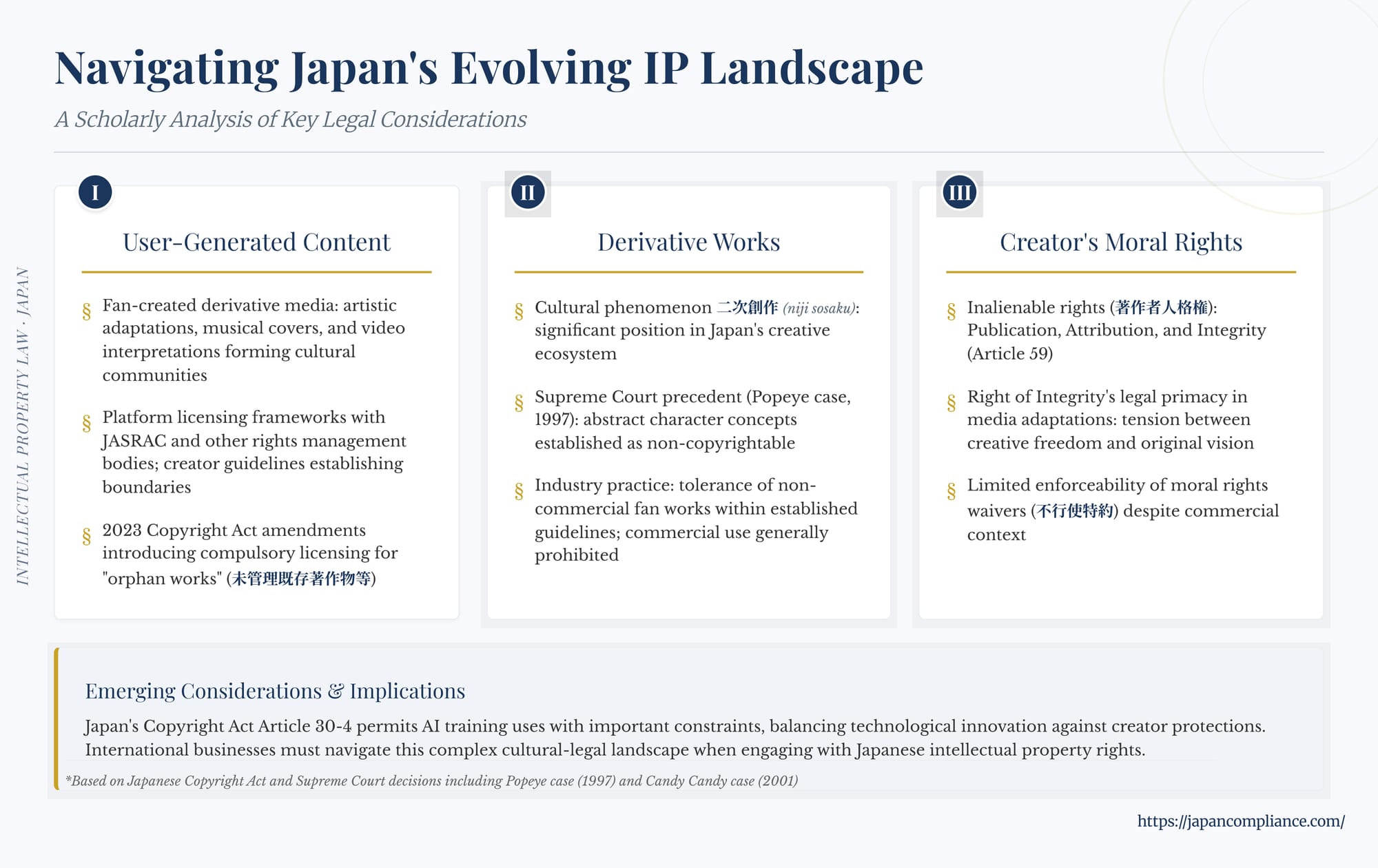

TL;DR: Japan’s IP landscape is shaped by a massive UGC culture, a tolerant yet legally complex environment for derivative works (niji sosaku), and strong, inalienable moral rights. International businesses must balance promotional use with rights clearance, respect creators’ integrity during adaptations, and monitor new rules on AI training and orphan-work licensing.

Table of Contents

- The Rise of User-Generated Content (UGC)

- Derivative Works: The Culture of Niji Sosaku

- Creator Rights in Media Adaptations

- Emerging Issues: AI and Beyond

- Practical Takeaways for Rights Holders & Platforms

Japan stands as a global powerhouse in creative content, exporting influential manga, anime, games, and characters worldwide. As digital platforms and global markets intertwine, engaging with Japanese intellectual property (IP) requires a nuanced understanding that goes beyond basic copyright principles. The landscape is constantly shifting, particularly concerning User-Generated Content (UGC), the culturally significant practice of creating derivative works (niji sosaku), and the robust protection afforded to creators' moral rights, especially during media adaptations. For international businesses licensing Japanese IP, collaborating with Japanese creators, or operating platforms hosting content in Japan, navigating these complexities is crucial.

The Rise of User-Generated Content (UGC)

The proliferation of smartphones, social media, and accessible creation tools has led to an explosion of User-Generated Content globally, and Japan is no exception. UGC encompasses a vast range of content, from fan art and cover songs posted online to gameplay videos and commentary. It's more than just entertainment; it functions as a vital communication tool, fostering communities where users interact, comment, and support creators through mechanisms like "tipping" (nagesen).

From a business perspective, UGC presents both opportunities and challenges. Companies increasingly leverage UGC in promotional campaigns, encouraging users to share experiences with products or services using specific hashtags, sometimes incentivized with giveaways. Embedding positive customer posts on corporate websites has also become common practice, harnessing the authentic voice of users for marketing. The sheer scale of platforms popular in Japan makes UGC an undeniably powerful force for brand engagement.

However, the legal implications, primarily concerning copyright, are significant. UGC often incorporates elements from existing copyrighted works – characters, music, video clips. Unauthorized use can lead to infringement claims. Recognizing this, various stakeholders have developed coping mechanisms:

- Platform Licensing: Music platforms often enter into comprehensive licensing agreements with collection societies like JASRAC (Japanese Society for Rights of Authors, Composers and Publishers). This allows users to legally create and share cover versions ("utattemita") or performance videos ("ensou shitemita") of managed songs under specific conditions.

- Creator Guidelines: Many IP holders, especially in the gaming and virtual YouTuber (VTuber) space, proactively issue guidelines outlining the permissible scope of fan creation, including streaming, video creation, and monetization.

- Technological Solutions: Platforms also implement content identification systems and takedown procedures to manage infringing uploads, although the sheer volume of UGC makes comprehensive policing difficult.

A major hurdle in utilizing existing UGC or even facilitating its creation is the difficulty in identifying rights holders and obtaining permissions, especially for works created by individual users who may not be affiliated with management bodies ("non-members"). Traditional copyright clearance processes can be cumbersome and slow.

Acknowledging these challenges and the economic potential of smoother UGC circulation, there have been government-level discussions and initiatives in Japan aimed at facilitating rights clearance. Recent amendments to the Copyright Act, set to take effect within a few years of their May 2023 promulgation, introduce a new compulsory licensing system for "orphan works" and publicly available works whose rights holders' intentions regarding use are unclear (mikanri kōhyō chosakubutsu tō). This system involves a government-designated body, potentially simplifying the process for using works where permission is hard to obtain directly. Furthermore, efforts are underway to build integrated, cross-sectoral rights information databases, potentially incorporating information voluntarily registered by individual creators, to streamline the search for rights holders. Collective licensing solutions, like the Digital Copyright License (DCL) offered by the Japan Academic Association for Copyright Clearance (JAC) and a partner, are also expanding, recently adding specific provisions for the internal use of copyrighted materials in corporate AI systems. While these developments signal progress, practical implementation and the extent to which individual UGC creators will participate remain key factors.

Derivative Works: The Culture of Niji Sosaku

Derivative works, known in Japan as niji sosaku (二次創作), hold a unique and significant place in the country's creative culture, particularly within fan communities (dōjin circles). These fan-made creations, often based on popular manga, anime, or game characters and worlds, range from fan fiction and fan art (dōjinshi) to figures, music arrangements, and games. Major events like Comiket attract hundreds of thousands, showcasing the scale and passion of this scene.

Legally, niji sosaku exists in a grey area. Under the Japanese Copyright Act, creating a derivative work based on an existing one typically requires the original author's permission, specifically involving the right of adaptation (hon'an-ken, Art. 27). Unauthorized derivative works that reproduce substantial creative expression from the original can constitute copyright infringement.

However, copyright protection extends only to the expression of ideas, not the ideas themselves. This distinction is crucial for character-based derivatives. The Japanese Supreme Court, notably in a case concerning the Popeye character (Supreme Court, July 17, 1997), established that a "character" as an abstract concept (personality, traits, general appearance) is not copyrightable in itself; only its specific, concrete expression (e.g., a particular drawing) is protected. Therefore, a niji sosaku work adopting the personality or general setting of a source work, but using entirely original artwork and plot, might not infringe the original's copyright, though trademark issues could still arise separately. Conversely, closely tracing artwork or reusing significant dialogue or plot elements is likely infringement.

Recognizing the cultural importance and promotional potential of fan activity, many Japanese copyright holders adopt a stance of tolerance towards non-commercial niji sosaku, often formalized through publicly available guidelines. These guidelines typically specify:

- Scope of Permission: Often limited to non-commercial, personal enjoyment, or small-scale distribution (like at dōjinshi events).

- Prohibited Content: Usually forbids content that harms the original work's image, is excessively violent or pornographic (unless the original work is itself in that genre), defames the creators, or promotes specific political or religious agendas.

- Attribution: May require clear indication that the work is a derivative and not official.

- Commercial Use: Generally prohibited or requires separate permission, although some guidelines are evolving to allow limited monetization on specific platforms (e.g., YouTube partner program revenue sharing).

These guidelines provide essential clarity for fans and reduce legal uncertainty, fostering a symbiotic relationship where fan activity can boost the original work's popularity. US companies licensing Japanese IP should be aware of any such existing guidelines related to the property.

It's also important to note that niji sosaku can itself be eligible for copyright protection. The Japanese Supreme Court clarified in a case involving the manga "Candy Candy" (Supreme Court, October 25, 2001) that the copyright in a derivative work belongs to the creator of the derivative only for the newly added creative elements. The rights in the underlying original work remain with the original author, who generally retains control over the derivative work's exploitation (Art. 28). This means that while a fan artist owns the copyright to their original contributions in a piece of fan art, they typically cannot commercialize it or authorize its further adaptation without the original rights holder's permission.

Creator Rights in Media Adaptations: The Primacy of Moral Rights

Perhaps one of the most critical, and potentially challenging, aspects of Japanese IP law for international businesses is the strong protection of Author's Moral Rights (chosakusha jinkaku-ken). Unlike economic rights (like reproduction or adaptation rights) which can be transferred or licensed, moral rights are considered deeply personal to the creator and are inalienable under Japanese law (Art. 59). They include:

- Right to Make the Work Public (kōhyō-ken, Art. 18): The right to decide if and when a work is published.

- Right of Attribution (shimei hyōji-ken, Art. 19): The right to be identified as the creator.

- Right of Integrity (dōitsu-sei hoji-ken, Art. 20): The right to prevent alterations, cuts, or modifications to the work against the creator's will.

The Right of Integrity is particularly relevant in the context of media adaptations (e.g., manga to film, game to anime). Adapting a work for a different medium inevitably requires changes – condensing plots, altering dialogue for screen, changing character designs for live-action. However, Article 20 grants the original creator the power to object to changes they deem harmful to their original intent or the work's essence. Exceptions exist for changes deemed unavoidable due to the nature of the work, the purpose of its use, or practical necessity (Art. 20(2)), but the threshold for these exceptions can be high, and the creator's view often carries significant weight.

This creates inherent tension in adaptation projects. Production companies and adapting writers/directors need creative freedom to make the work suitable for the new medium, while the original creator has a legal right to protect their work's integrity. Recent high-profile difficulties in Japan, such as conflicts arising during the production of a TV drama based on a popular manga where the original author felt compelled to intervene directly in the scriptwriting process due to concerns over faithfulness to the source material, underscore the practical challenges. These situations highlight the potential for serious breakdowns when communication fails or the creator's moral rights are not adequately respected during the adaptation process.

In practice, production contracts often include clauses where the creator agrees not to exercise their moral rights (fukoshi tokuyaku). The legal validity and enforceability of these "waivers" are debated, given the inalienability principle enshrined in Article 59. While courts might uphold such agreements in some commercial contexts, particularly if freely entered into by sophisticated parties, a blanket waiver may not always be enforceable, especially if the changes significantly deviate from the original creator's intent or damage their reputation. The power imbalance often present between individual creators and large production companies or publishers further complicates the assessment of whether such consent is truly voluntary.

Case law suggests that interpreting the scope of any consent given by a creator requires careful consideration of the specific circumstances. For instance, in a recent dispute involving script alterations (Osaka District Court, May 30, 2024), the court analyzed whether a junior scriptwriter's general agreement to collaborate with a senior scriptwriter constituted broad consent to significant, uncommunicated changes made later. The initial ruling suggested that consent to collaboration does not automatically extend to substantial alterations made without specific approval, emphasizing the need for ongoing communication and respect for the original writer's input, especially when significant changes are contemplated. (Note: This district court decision was later overturned on appeal, highlighting the ongoing legal complexity).

For US companies involved in adaptations, proactive communication, clearly defined approval processes for changes, and genuine efforts to understand and respect the original creator's vision are paramount, even when contractual waivers are in place. Ignoring moral rights can lead to disputes, production delays, and reputational damage.

Emerging Issues: AI and Beyond

The Japanese IP landscape continues to evolve, with generative AI posing new questions. Japan's Copyright Act includes a provision (Art. 30-4, introduced in 2019) that permits the use of copyrighted works for information analysis, including AI training, for purposes other than "enjoying the thoughts or sentiments expressed" in the work, unless it "unreasonably prejudices the interests of the copyright owner". This is considered relatively permissive compared to some other jurisdictions, particularly regarding commercial AI development.

However, ambiguity remains regarding the scope of "unreasonable prejudice" and the legality of using data scraped without authorization. Furthermore, the output of generative AI raises separate infringement concerns if it is substantially similar to existing works. The potential for AI to generate content mimicking creator styles or even being passed off as human-created work ("AI ghostwriters") also presents challenges for authenticity and rights management within the UGC and derivative works ecosystems. Government guidelines encourage AI businesses to implement safeguards and respect IP rights, often favoring licensing arrangements, but the legal boundaries are still being tested. Technical solutions like content credentialing technologies are being explored by platforms to label AI-generated content, but widespread adoption and effectiveness are yet to be seen.

Conclusion

Japan's content industry thrives on creativity, fan engagement, and the strong connection between creators and their works. For businesses operating in this space, understanding the nuances of Japanese IP law is essential. Key takeaways include:

- UGC requires careful management: Balancing promotional use with copyright compliance and navigating rights clearance complexities is vital. New systems aim to simplify this, but challenges remain.

- Niji Sosaku is culturally embedded: While legally complex, derivative works are often tolerated non-commercially. Official guidelines are increasingly common and provide crucial boundaries.

- Moral Rights are paramount: Creators' Right of Integrity holds significant weight, especially in adaptations. Contractual waivers are common but not always absolute. Respectful collaboration and clear communication are key to avoiding disputes.

- The landscape is dynamic: AI, evolving platform policies, and new legislation continuously reshape the environment. Staying informed about legal developments and industry best practices is crucial.

Successfully navigating Japan's IP landscape requires more than just legal knowledge; it demands an appreciation for the cultural context surrounding content creation and fan activity, and a commitment to respecting the deeply ingrained rights and sensitivities of creators.

- Protecting Your IP in Japan: Strategies for Patents, Trademarks, and Copyright

- Software Development in Japan: A Guide to Copyright Ownership and IP Clauses

- Generative AI in Japan: Understanding Copyright Risks and Opportunities

- Agency for Cultural Affairs — Q&A on Copyright and Derivative Works

https://www.bunka.go.jp/seisaku/chosakuken/seidoseibi/faq/index.html