Camera Surveillance in Japan: APPI Rules, Facial-Recognition Guidance & Compliance Tips for US Businesses

TL;DR

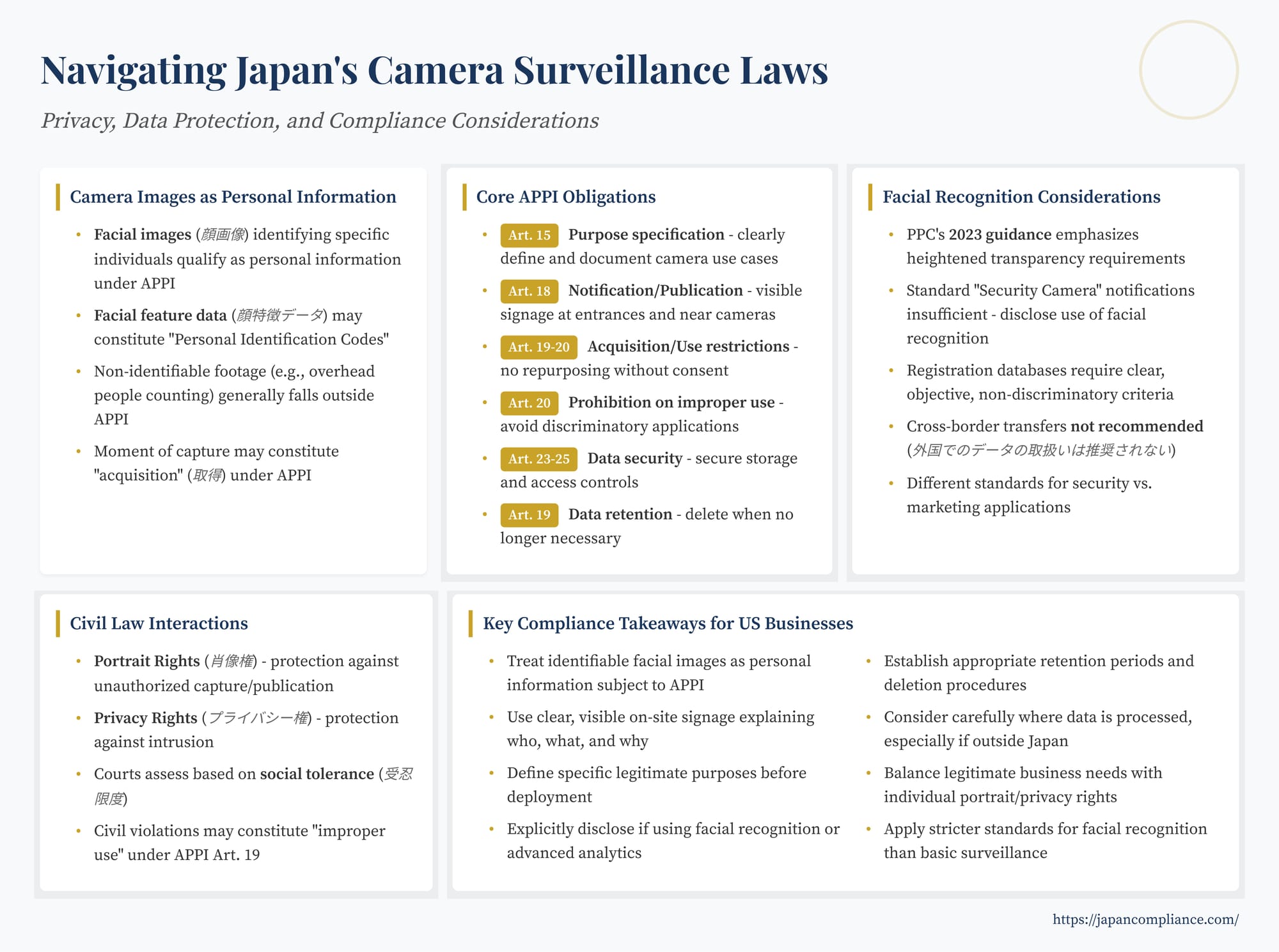

- Identifiable camera images are “personal information” under Japan’s APPI; capture alone triggers obligations.

- Facial-recognition systems face stricter transparency and purpose-limitation tests under PPC 2023 guidance.

- Clear signage, narrowly defined purposes, robust security measures and retention limits are essential for compliance.

Table of Contents

- Defining “Personal Information” in Camera Footage under APPI

- Core APPI Obligations When Using Cameras

- Specific Considerations for Facial Recognition

- Crime Prevention vs. Marketing Analytics Uses

- Interaction with Civil Law: Portrait and Privacy Rights

- Conclusion: Key Takeaways for Compliance

The ubiquity of cameras in modern society – from smartphones and security systems to AI-powered robots and marketing analytics tools – presents complex legal challenges worldwide. For US businesses operating in Japan or handling data related to Japanese individuals, understanding the specific nuances of Japanese law concerning camera images is crucial for maintaining compliance and mitigating risk. Japan's primary data protection legislation, the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI), along with related guidelines and civil law principles, creates a distinct regulatory environment that requires careful navigation.

This article provides an overview of the key legal considerations surrounding the use of camera images in Japan, focusing on issues relevant to corporate legal and business professionals.

Defining "Personal Information" in Camera Footage under APPI

A fundamental question is whether camera footage constitutes "Personal Information" (個人情報 - kojin jōhō) under the APPI. The answer significantly impacts the obligations imposed on businesses handling such data.

Facial Images and Identifiability:

The general consensus, reflected in guidance from Japan's Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) and legal commentary, is that facial images (顔画像 - kao gazō) that allow for the identification of a specific individual generally qualify as personal information. The key criterion is identifiability. If an image, either alone or when combined with other readily available information, can pinpoint a specific person, it falls under the APPI's scope.

This often extends to facial feature data (顔特徴データ - kao tokuchō dēta), which is data extracted from facial images used, for instance, in facial recognition systems. Even if the original image is deleted, this extracted data, if capable of identifying an individual (often treated as potentially falling under "Personal Identification Codes" - 個人識別符号, kojin shikibetsu fugō), remains personal information subject to APPI rules.

Contrast with Non-Identifiable Data:

Conversely, images captured in a way that precludes individual identification generally fall outside the scope of APPI's core obligations. Examples might include:

- Overhead cameras solely used for counting people where faces are not captured clearly.

- Footage anonymized immediately upon capture, rendering individuals unidentifiable.

However, businesses must be cautious. Even if the primary intent is non-identifying data collection (like people counting), if faces are incidentally captured and identifiable, APPI obligations may still arise, at least momentarily at the point of capture.

"Acquisition" vs. "Collection": A Nuance?

Interestingly, in the context of generative AI, the PPC has distinguished between "collection" and "acquisition" (取得 - shutoku), suggesting that merely collecting data doesn't automatically equate to acquiring it under the APPI if steps are taken to prevent the acquisition of sensitive information. However, for camera images, the traditional interpretation holds: the moment an identifiable image is captured, "acquisition" under the APPI occurs, triggering relevant obligations like purpose specification and notification. This distinction highlighted for AI has not generally been applied retroactively to reinterpret camera surveillance practices.

Comparison with GDPR/US Laws:

It's worth noting that while APPI treats identifiable facial images as personal information, its approach differs slightly from other regimes. The GDPR, for example, classifies biometric data used for unique identification (including facial images in many contexts) as a "special category of personal data," requiring stricter processing conditions. US laws vary, with states like Illinois (BIPA) and California (CCPA/CPRA) having specific definitions and requirements for biometric information, including facial scans. Under APPI, facial data itself isn't automatically deemed sensitive personal information (要配慮個人情報 - yō-hairyo kojin jōhō) unless used in a manner that reveals sensitive attributes or involves discriminatory intent.

Core APPI Obligations When Using Cameras

Once it's established that camera footage involves personal information, businesses (referred to as "business operators handling personal information" - 個人情報取扱事業者, kojin jōhō toriatsukai jigyōsha) must adhere to several key APPI requirements.

1. Specification of Utilization Purpose (利用目的の特定 - riyō mokuteki no tokutei)

Businesses must specify the purpose for which they are collecting and using camera image data "as specifically as possible." Vague purposes are insufficient.

- Security/Crime Prevention: Purposes like "crime prevention," "shoplifting deterrence," or "ensuring facility safety" are common. Guidance suggests simply stating "crime prevention" might not be specific enough, especially if facial recognition is used. More detail, potentially referencing specific types of crime being prevented (e.g., theft, trespassing) or safety scenarios (e.g., accident prevention, missing person searches), may be advisable depending on the context and technology used.

- Marketing/Analytics: Purposes could include "analyzing customer traffic flow," "measuring storefront engagement," "understanding customer demographics (age/gender estimation)," or "improving store layout."

- Operational Efficiency: Examples include "monitoring queue lengths," "optimizing staffing levels," or "analyzing workspace utilization."

The purpose must be determined before or at the time of acquiring the personal information.

2. Notification or Publication of Utilization Purpose (通知・公表 - tsūchi・kōhyō)

Generally, the specified utilization purpose must be either directly notified to the individual (the data subject or 本人 - honnin) or publicly announced before or promptly after acquiring the personal information.

- Methods:

- On-site Signage: This is the most common and often necessary method for physical locations equipped with cameras. Signs should be clear, easily visible, and placed strategically at entrances or near cameras.

- Online Privacy Policy: While necessary for overall data handling transparency, relying solely on an online privacy policy is generally insufficient for camera surveillance notification, as individuals entering a physical space cannot reasonably be expected to have reviewed the website beforehand. The online policy can supplement on-site notices, providing more detailed information.

- QR Codes: Signage can include QR codes linking to a webpage with more detailed information, including the full privacy policy and specific details about camera use.

- Content: The notice must clearly convey:

- The entity responsible for collecting the data (the business operator's name). This is crucial for accountability.

- The specific utilization purpose(s).

- Contact information for inquiries or exercising data subject rights.

- If facial recognition or other advanced analytics are used, this should ideally be disclosed explicitly, as per PPC guidance recommendations for transparency.

- PPC Guidance on Facial Recognition: The PPC's document "Regarding the Use of Camera Systems with Facial Recognition Functions for Crime Prevention and Safety Assurance" (March 2023) emphasizes transparency. It suggests that simple signs like "Security Cameras in Operation" are inadequate when facial recognition is employed for crime prevention or safety. Clearer indication of the technology's use is encouraged to avoid causing undue anxiety among individuals being filmed.

- Marketing vs. Security: Notification requirements might be interpreted more strictly for marketing purposes, especially if the data collection is less expected or avoidable by the individual. The concept of "avoidability" (避けられないさ - sakerarenai-sa), discussed in resources like the "Camera Image Utilization Guidebook," suggests that where individuals cannot easily avoid being captured (e.g., public transit hubs, essential pathways), transparency measures should be more robust.

- Exceptions: There are limited exceptions to the notification/publication requirement, such as when the utilization purpose is "obvious from the circumstances of acquisition." Historically, traditional, passive security cameras were sometimes considered to fall under this exception, but with advanced capabilities like facial recognition, relying on this exception is increasingly risky and generally discouraged. Combining security with other purposes (like marketing) negates the "obviousness" of the security purpose, requiring clear notification of all purposes.

3. Restrictions on Acquisition and Use (取得・利用の制限 - shutoku・riyō no seigen)

- Proper Acquisition: Personal information must not be acquired through deceit or other improper means (不正の手段 - fusei no shudan). This clearly prohibits covertly installed cameras or misleading individuals about the purpose of filming. PPC guidance also suggests that failing to provide adequate notice, especially for facial recognition systems, could potentially be viewed as improper acquisition.

- Purpose Limitation: Personal information acquired via cameras cannot be used for purposes beyond those specified and notified/published, unless the individual's consent is obtained or an exception applies (e.g., legal requirement, emergency). For instance, security footage collected for crime prevention cannot typically be repurposed for marketing analytics without consent.

- Prohibition on Improper Use (不適正利用の禁止 - futekisei riyō no kinshi): Added in a recent APPI amendment, this provision prohibits using personal information in a way that facilitates or promotes illegal or improper acts. This includes use that could lead to discrimination. For example, using facial recognition data to unfairly discriminate against individuals based on assumptions derived from their appearance could violate this clause. The PPC guidance explicitly links discriminatory handling based on sensitive attributes inferred from camera data (like health status or ethnicity, even if not directly collected) to this prohibition. Notably, the guidance also suggests that uses infringing upon rights under civil law (like privacy or portrait rights) could potentially constitute "improper use" under APPI.

4. Sensitive Personal Information (SPI) (要配慮個人情報 - yō-hairyo kojin jōhō)

APPI requires explicit consent for acquiring SPI, which includes race, creed, social status, medical history, criminal record, etc. As mentioned, facial data itself is not automatically SPI under APPI. However, if camera systems (especially those using AI) are used to infer SPI (e.g., inferring health conditions, ethnicity) or if the system is used specifically to identify individuals based on known SPI (e.g., identifying individuals with specific medical conditions or criminal records for discriminatory purposes), this could trigger SPI consent requirements or fall under the improper use prohibition.

5. Data Security Management Measures (安全管理措置 - anzen kanri sochi)

Businesses must take necessary and appropriate measures to prevent the leakage, loss, or damage of the personal data they handle. This includes:

- Technical measures (access controls, encryption, secure storage).

- Organizational measures (appointing a responsible person, establishing internal rules, training employees, supervising contractors).

- Physical measures (securing server rooms, controlling access to premises).

For camera systems, this involves securing the footage storage (on-device, local server, cloud), managing access rights strictly, and ensuring secure data transfer.

The PPC guidance on facial recognition systems for crime prevention/safety explicitly notes that handling such data outside of Japan is not recommended (外国でのデータの取扱いは推奨されない - gaikoku de no dēta no toriatsukai wa suishō sarenai). While not an outright legal prohibition for all camera data, this strong recommendation signals heightened concern about cross-border transfers of potentially sensitive image data, especially for security applications, likely due to differing legal protections and government access regimes abroad. US businesses using cloud services hosted outside Japan for storing or processing camera footage from Japan should carefully evaluate this guidance and ensure robust security and contractual safeguards are in place, potentially conducting a transfer impact assessment.

6. Data Retention and Deletion (データの保有・消去 - dēta no hoyū・shōkyo)

APPI obliges businesses to endeavor to delete personal data without delay when it is no longer necessary for the specified utilization purpose. While this is phrased as an "endeavor" obligation (努力義務 - doryoku gimu), it's a critical compliance point.

There are no prescribed maximum retention periods in the APPI itself. The "necessity" depends on the utilization purpose.

- For security footage, retention might be necessary for a period relevant to investigating incidents (e.g., 30-90 days, depending on the context and risk).

- For marketing analytics, data might only be needed until aggregated insights are generated, after which the raw identifiable footage should be deleted or fully anonymized.

Businesses should establish clear internal policies defining retention periods based on specific purposes and implement mechanisms for regular deletion. Indefinite storage without a clear justification is non-compliant.

Specific Considerations for Facial Recognition

The PPC's 2023 guidance places particular emphasis on cameras equipped with facial recognition capabilities, recognizing their heightened potential impact on privacy. Key takeaways include:

- Enhanced Transparency: As noted, standard "camera surveillance" notices are likely insufficient. Clear disclosure that facial recognition is being used is recommended.

- Registration Databases: The guidance specifically addresses systems that compare captured faces against a pre-registered database (e.g., known shoplifters, authorized personnel, missing persons). It stresses the need for clear, objective, and necessary criteria for registering individuals in such databases. Registration based on discriminatory factors or assumptions (e.g., based on appearance suggesting a potential disability) is cautioned against as potentially improper or discriminatory use.

- Accuracy and Security: Implicitly, the use of facial recognition necessitates higher standards for data accuracy and security management due to the potentially significant consequences of misidentification or data breaches.

Crime Prevention vs. Marketing Analytics Uses

While both security/crime prevention and marketing analytics fall under APPI if personal information is processed, the practical considerations and potential legal risks can differ.

- Expectation of Privacy: Individuals may have a lower expectation of privacy regarding basic security surveillance in many commercial settings compared to having their facial features analyzed for marketing insights or demographic profiling.

- Justification: Crime prevention and safety assurance are often seen as more compelling justifications for camera use than purely commercial marketing interests, potentially influencing the assessment of necessity and proportionality.

- Transparency: As discussed, transparency requirements, particularly around advanced analytics like facial recognition or attribute estimation for marketing, might demand more explicit disclosure than for standard security monitoring.

- "Avoidability": In marketing contexts within quasi-public spaces (e.g., shopping malls, transit hubs), providing individuals with genuine choices to avoid data collection (if feasible) might be considered a positive factor in assessing the appropriateness of the processing.

Interaction with Civil Law: Portrait and Privacy Rights

Beyond the APPI, the use of cameras implicates civil law rights, primarily Portrait Rights (肖像権 - shōzōken) and the broader Right to Privacy (プライバシー権 - puraibashīken). These are primarily protected under tort law.

- Portrait Rights: Generally protects individuals from having their likeness captured and/or published without consent, especially if it causes psychological distress.

- Privacy Rights: Protects against unreasonable intrusion into one's private life or the public disclosure of private facts.

Japanese courts typically assess infringements based on a balancing test, considering factors like the purpose of the filming, the location (public vs. private space), the manner of filming, the necessity of the filming, and whether the intrusion or distress caused exceeds the limits of social tolerance (受忍限度 - junin gendo).

Capturing identifiable images in public spaces isn't automatically unlawful, but persistent tracking, intrusive filming, or publication without consent can lead to liability. Notably, as mentioned in the PPC guidance context, actions deemed violations under civil law (e.g., highly intrusive surveillance found to be a privacy tort) could potentially be considered "improper use" under APPI Article 19, creating an overlap between regulatory compliance and tort liability.

Conclusion: Key Takeaways for Compliance

Navigating the legal requirements for camera use in Japan demands a proactive and context-sensitive approach. Key takeaways for US businesses include:

- Assume Facial Images are Personal Information: Treat identifiable facial images and derived feature data as personal information subject to APPI.

- Specify Purpose Clearly: Define and document specific, legitimate purposes for camera use before deployment.

- Prioritize On-Site Notification: Use clear, visible signage explaining who is collecting data, for what purpose, and how to get more information. Supplement with online policies but don't rely on them alone. Be explicit if using facial recognition or advanced analytics.

- Limit Data Collection and Use: Only collect what's necessary for the specified purpose and do not repurpose data without consent. Avoid covert filming.

- Implement Robust Security: Secure camera feeds, storage, and access controls. Carefully consider the implications of using overseas data processors, especially for facial recognition data used for security.

- Establish Retention Limits: Define reasonable retention periods based on purpose and ensure data is securely deleted when no longer needed.

- Heightened Scrutiny for Facial Recognition: Apply stricter transparency and purpose-justification standards when using facial recognition. Ensure any registration databases have clear, objective criteria.

- Consider Civil Rights: Be mindful of portrait and privacy rights under tort law, ensuring filming is not unduly intrusive and respects individual dignity.

- Stay Updated: The legal and technological landscape is evolving. Monitor updates from the PPC and developments in case law.

By understanding and adhering to these principles derived from the APPI, related guidance, and civil law, US businesses can leverage camera technology responsibly while minimizing legal and reputational risks in the Japanese market.

- Cyber-Incident Response in Japan: APPI Compliance & Cybersecurity Basics Explained

- Ransomware in Japan: APPI Duties, Sanctions Risk & Practical Response Guide

- AI Training Data and Copyright in Japan: Understanding Article 30-4 Exceptions

- PPC Guidance on Camera Systems with Facial Recognition (Mar 2023, PDF)

- PPC Q&A on Camera Surveillance and Privacy (Japanese)