Navigating Japan's 2024 FIEA Reforms: Key Changes to Takeover Bids and Large Shareholding Reports

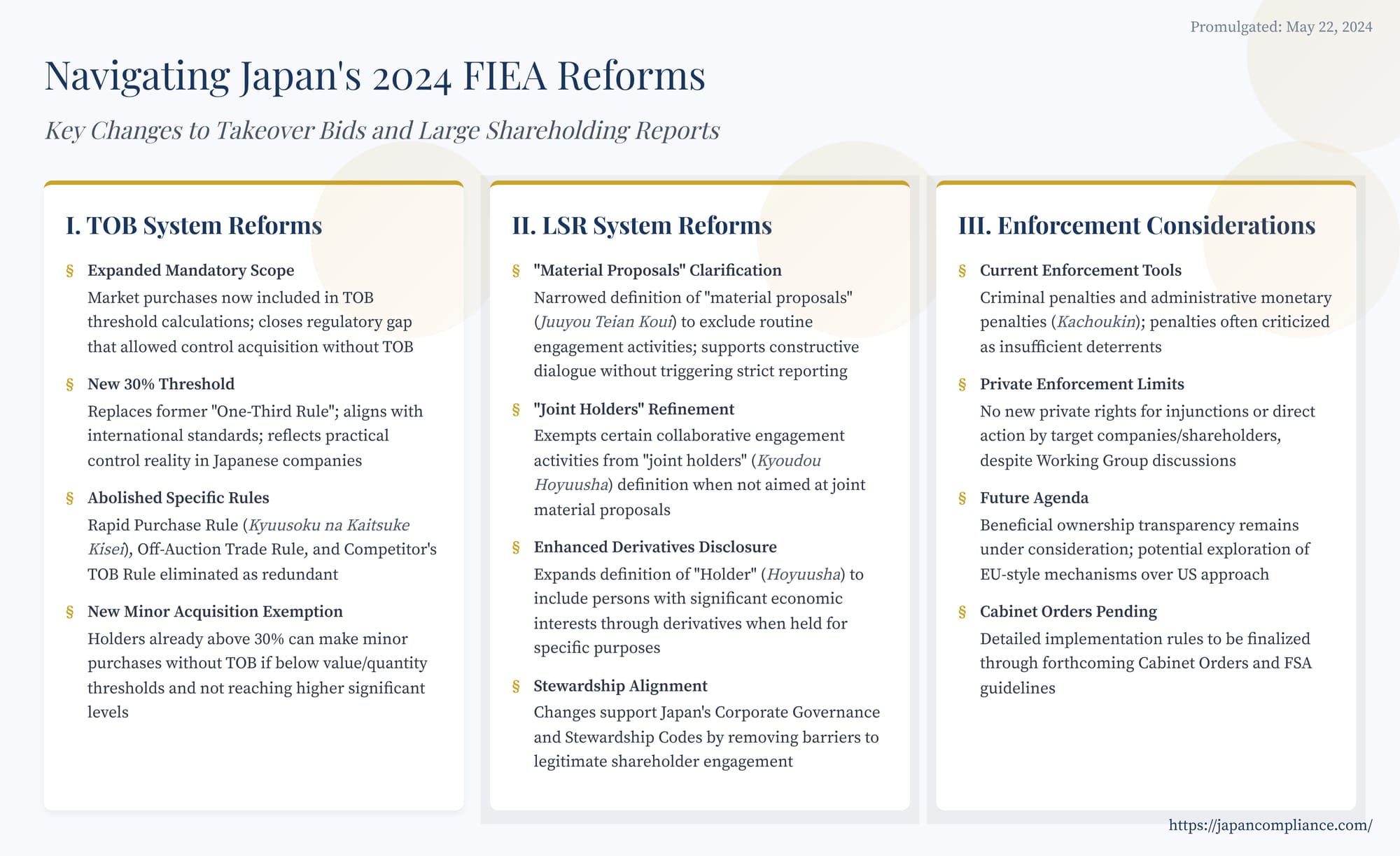

TL;DR: Japan’s 2024 FIEA amendment closes the “market-sweep” loophole by counting on-exchange purchases toward a new 30 % mandatory-TOB trigger, lowers the Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) threshold to 3 %, and widens derivative and joint-holder disclosure. Enforcement remains modest, but transparency requirements now align more closely with global standards.

Table of Contents

- Part 1: Overhauling the Takeover Bid (TOB) System

- Part 2: Reforming the Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) System

- Part 3: Enforcement and Future Considerations

- Conclusion

Introduction

Japan's capital markets have undergone significant evolution, attracting increased attention from global investors and corporations. Parallel to this evolution, the legal landscape governing mergers, acquisitions, and shareholder disclosures is also shifting. A pivotal development is the recent amendment to Japan's Financial Instruments and Exchange Act (FIEA), alongside the Act on Investment Trusts and Investment Corporations. This amending legislation (Act No. 32 of 2024), promulgated on May 22, 2024, introduces substantial changes to the Takeover Bid (TOB) system and the Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) system.

These reforms stem largely from recommendations made in the December 25, 2023 report by the Financial System Council's "Working Group on Takeover Bid System, Large Shareholding Reporting System, etc." The primary drivers include the need to address acquisition strategies that previously circumvented TOB rules, enhance shareholder protection, promote constructive dialogue between investors and companies, and align certain aspects of Japanese regulation with international standards.

Understanding these changes is crucial for any foreign entity involved in or contemplating investments, M&A activities, or significant shareholdings in Japanese listed companies. This article provides an analysis of the key modifications to the TOB and LSR regimes under the 2024 FIEA reforms.

Part 1: Overhauling the Takeover Bid (TOB) System

The most significant changes arguably lie within the TOB regulations, designed to ensure fairness and transparency during significant share acquisitions that could impact corporate control.

1.1. Background: Addressing Circumvention via Market Purchases

Historically, Japan's mandatory TOB rules were triggered primarily by off-market transactions (purchases outside the stock exchange) exceeding certain ownership thresholds (like the "5% Rule" for purchases from more than 10 people in 60 days, or the "One-Third Rule" for substantial off-market acquisitions). Crucially, purchases made directly on the open market through the stock exchange (known as shijo-nai torihiki or tachiai-nai torihiki) were generally exempt from the mandatory TOB requirement, even if they resulted in a controlling stake.

This created a regulatory gap. Acquirers could gradually accumulate significant stakes, potentially reaching de facto control, through open market purchases without being obligated to launch a formal TOB. This practice raised concerns about fairness to other shareholders, who might not receive a control premium or have sufficient information and time to evaluate the change in control. Notable cases, including a widely discussed 2021 Supreme Court decision involving a dispute over defensive measures against such gradual market accumulation by an acquirer at a machinery manufacturing company, highlighted the practical challenges and coercive potential of this approach under the old rules. Shareholders might feel pressured to sell into the market quickly if they feared being left as minority shareholders under a new controlling entity, potentially accepting a lower price than a formal TOB might offer. The Financial System Council working group identified this lack of transparency and potential for coercion in market sweeps as a key area needing reform.

1.2. Key Change 1: Expanded Mandatory TOB Scope and New 30% Threshold

The 2024 amendments fundamentally reshape the mandatory TOB triggers:

- Inclusion of Market Purchases: The most critical change is that purchases made on the stock exchange (open market purchases) are now included when calculating whether a mandatory TOB threshold has been crossed. This closes the previous regulatory gap.

- New 30% Threshold: The primary threshold triggering a mandatory TOB is now set at 30% of voting rights (Revised FIEA Art. 27-2, Para. 1, Item 1). This replaces the former "One-Third Rule" (approximately 33.3%) that applied mainly to off-market and certain off-auction trades. An acquirer whose voting rights ratio will exceed 30% after a purchase (whether on-market or off-market, excluding certain exemptions) must conduct the purchase via a formal TOB.

Rationale for the Changes:

- Preventing Circumvention: Directly addresses the issue of acquirers gaining control through market sweeps without triggering TOB obligations.

- Shareholder Protection: Ensures that significant acquisitions potentially affecting corporate control occur transparently, providing all shareholders with equal opportunity to tender shares, access to information (through the TOB registration statement), sufficient time for consideration, and potentially a share of the control premium.

- International Alignment: The 30% threshold is more aligned with standards in many other jurisdictions, notably the European Union, where mandatory bid obligations often arise at similar levels.

- Reflecting Control Realities: In many Japanese listed companies, holding 30% of voting rights is practically sufficient to block special resolutions (which typically require a two-thirds majority of votes cast) and exert significant influence over ordinary resolutions. The new threshold reflects this reality.

1.3. Key Change 2: Abolition of Certain Specific TOB Rules

Consequent to the main reform broadening the mandatory TOB scope, several specific rules considered redundant or outdated were repealed:

- Rule for Off-Auction Trades (ToSTNeT, etc.): The specific rule mandating a TOB for acquisitions via off-auction market systems exceeding the one-third threshold (former FIEA Art. 27-2, Para. 1, Item 3) was removed, as such purchases now fall under the general 30% rule applicable to both on- and off-market trades.

- Rule During Competitor's TOB: The rule requiring a holder already exceeding one-third ownership to use a TOB when acquiring an additional 5% during another party's active TOB (former FIEA Art. 27-2, Para. 1, Item 5) was also repealed. The rationale is that the main 30% rule and other existing regulations (like the prohibition on acquirers making separate market purchases during their own TOB) sufficiently cover the objectives of ensuring fair competition between bidders.

- Rapid Purchase Rule (Kyuusoku na Kaitsuke Kisei): The complex "Rapid Purchase Rule" (former FIEA Art. 27-2, Para. 1, Item 4) was abolished. This rule mandated a TOB if, within a three-month period, an acquirer obtained over 10% of shares, with over 5% acquired through specific methods (like off-market or off-auction trades), and the total holding exceeded one-third. Its original intent was primarily to prevent circumvention of the old One-Third Rule by combining market and off-market purchases rapidly. With market purchases now directly included in the main 30% threshold, the primary anti-circumvention rationale was deemed obsolete.

However, the abolition of the Rapid Purchase Rule sparked some debate. Some commentators argued it also served as a "speed limit" on stakebuilding and offered a degree of protection similar to minimum price rules found elsewhere (by preventing an immediate low-ball TOB after a high-priced off-market block purchase). The Financial System Council WG report had initially suggested retaining and modifying this rule to explicitly include market purchases. The final legislation, however, opted for abolition, potentially reflecting concerns that retaining it might unduly restrict legitimate toehold acquisitions prior to a full TOB. While the main circumvention route is closed, the removal of this specific speed bump means rapid stake accumulation below 30% followed immediately by a TOB is, on the face of the statute, less restricted than under the WG's proposal. Nevertheless, legal experts suggest that transactions structured to deliberately evade the spirit of the TOB rules could still be scrutinized as a single, integrated transaction requiring a TOB under general anti-avoidance principles.

1.4. Key Change 3: New Exemption for Minor Acquisitions Above 30%

To avoid excessive regulation, a new exemption was introduced (subject to details in forthcoming Cabinet Orders). A person already holding more than 30% of voting rights can make further minor purchases without conducting a TOB, provided:

- The number of shares or total value of the purchase is significantly small (precise thresholds to be defined by Cabinet Order).

- The purchase does not result in the holder reaching or exceeding a higher significant threshold, such as two-thirds (the specific upper limit, likely two-thirds, will be set by Cabinet Order).

- The purchase is not a "Specified Off-Market Purchase" (tokutei shijo-gai kaitsuke tou), which refers to off-market purchases from numerous sellers (Revised FIEA Art. 27-2, Para. 1, Item 2) that retain characteristics necessitating TOB procedures due to potential pressure on sellers.

This allows major shareholders to make small adjustments to their holdings without the burden of a full TOB, as long as they don't cross further significant control thresholds.

1.5. Flexibility and Operational Issues

The Working Group also discussed enhancing the flexibility of TOB regulations. While the 2024 amendments focus on structural rule changes, debates continue regarding operational flexibility. Suggestions included granting regulatory authorities (like the Financial Services Agency - FSA) more explicit power to grant exemptions from certain rigid rules (e.g., the prohibition on an offeror making separate purchases during the TOB period) based on the specific circumstances of a case.

The idea of establishing a body with specialized expertise and judgment capabilities, sometimes referred to as the "Panel concept" (inspired by the UK Takeover Panel), was also discussed. Proponents argued this could allow for more nuanced, principles-based application of the rules. However, concerns about predictability, potential for regulatory discretion, and the significant resources required meant that such a major institutional reform was not pursued in the 2024 amendments. The focus remained on legislative rule changes, though the FSA may issue guidelines to clarify interpretations.

Part 2: Refining the Large Shareholding Reporting (LSR) System

The LSR system requires investors whose holding ratio of voting shares in a listed company exceeds 5% to file a report with the authorities (and make it publicly available via EDINET), detailing their identity, holding purpose, funding sources, and related parties. Subsequent changes of 1% or more, or changes in material details, trigger amendment reports. The 2024 reforms aim to improve the system's effectiveness and relevance in the context of modern investment practices and corporate governance.

2.1. Background: Balancing Transparency and Shareholder Engagement

The LSR system's primary goal is market transparency – informing the market and the issuer about the presence and intentions of significant shareholders. However, ambiguities in the existing rules were seen as potentially hindering constructive dialogue (taiwa) between investors (especially institutional investors) and companies, a key element of Japan's Stewardship Code and Corporate Governance Code. Specifically, the definitions of "material proposals" and "joint holders" were areas of concern. Additionally, the rise of complex financial instruments created potential gaps in disclosure regarding economic interests held through derivatives.

2.2. Key Change 1: Clarifying "Material Proposals" (Juuyou Teian Koui)

- Significance: An investor's stated "holding purpose" (hoyuu mokuteki) in the LSR impacts reporting deadlines. Those holding shares purely for investment purposes without intending to make "material proposals" regarding the issuer's business activities can use a simplified, less frequent reporting schedule (Special Reports or Tokurei Houkoku, typically filed bi-monthly based on set dates). If the intent includes making material proposals, the standard, more burdensome reporting applies (filing within 5 business days of crossing the threshold or making a 1% change).

- The Issue: The scope of "material proposals" (defined by Cabinet Order under FIEA Art. 27-26, Para. 1) was considered unclear. Legitimate engagement activities by institutional investors under the Stewardship Code (e.g., discussing governance improvements, capital allocation, or environmental policies) could potentially be interpreted as falling under the broad categories of material proposals (like proposing changes to dividends or major organizational changes), forcing them onto the stricter reporting schedule and thus chilling engagement.

- The Reform (via forthcoming Cabinet Order): The reform aims to narrow or clarify the definition of "material proposals" that disqualify investors from using Special Reports. The direction indicated by the WG report suggests focusing on proposals directly related to corporate control (e.g., acquiring a certain percentage of voting rights, nominating directors) or proposals presented in a manner that doesn't leave the final decision to management's discretion (e.g., binding shareholder proposals on specific business changes). Routine dialogue and suggestions regarding governance or strategy intended to enhance corporate value, where management retains decision-making authority, are expected to be less likely to trigger the stricter reporting requirement, thereby facilitating constructive investor-company engagement.

2.3. Key Change 2: Refining "Joint Holders" (Kyoudou Hoyuusha)

- Significance: The shareholdings of "joint holders" are aggregated when calculating the 5% LSR threshold (FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 4). Joint holders are defined as persons who have an "agreement" (goui) with the main holder to jointly acquire/dispose of shares or exercise voting rights or other shareholder rights (FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 5).

- The Issue: The term "agreement" could be interpreted broadly to include informal understandings or collaborations. Institutional investors engaging in collective engagement (e.g., jointly approaching a company about ESG issues) feared being deemed joint holders. This would necessitate complex information sharing among them to track aggregated holdings and file timely reports, creating significant practical burdens and discouraging collaboration.

- The Reform (FIEA Amendment & forthcoming Government Ordinance): The definition of "joint holders" in FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 5 was amended to explicitly exclude situations meeting certain criteria (to be detailed in ordinances). The intent is to carve out exceptions for collaborative engagement among specific types of investors (likely institutional investors like asset managers, banks, etc.). The carve-out is expected to apply only if the agreement's purpose is not to jointly make material proposals and the agreement concerns only the joint exercise of rights on a case-by-case basis (e.g., specific shareholder meeting proposals), rather than continuous, concerted action that amplifies their collective influence on management. This aims to reduce the chilling effect on legitimate collaborative stewardship activities.

2.4. Key Change 3: Enhancing Derivatives Disclosure

- The Issue: Investors could gain significant economic exposure to a company, equivalent to a large shareholding, through cash-settled equity derivatives (like total return swaps) without actually holding the shares or voting rights. This allowed potential circumvention of LSR disclosure obligations, masking substantial economic interests from the market. While existing interpretations already captured some derivative positions where the holder effectively controlled the underlying shares, gaps remained.

- The Reform (FIEA Amendment & forthcoming Government Ordinance): The definition of "Holder" (hoyuusha) in FIEA Art. 27-23, Para. 3 was expanded. A new item (Item 3) was added to include persons holding rights related to derivative transactions involving shares (kabuken tou ni kakaru derivative torihiki ni kakaru kenri wo yuusuru mono), even if they don't hold shares directly or through nominees, if they hold these derivatives for specific purposes (to be defined by Cabinet Order). The purposes cited by the WG report include: (a) intending to acquire the underlying shares from the counterparty, (b) intending to influence the voting rights attached to the shares held by the counterparty (e.g., as a hedge), or (c) intending to engage with the issuer based on the leverage provided by such a derivative position (e.g., demanding material changes). This change aims to capture significant economic interests and potential influence gained through derivatives that were previously outside the scope of disclosure.

Part 3: Enforcement and Future Considerations

While the 2024 reforms address key structural aspects of the TOB and LSR systems, significant questions remain regarding enforcement and the broader issue of shareholder transparency.

3.1. Enforcement Challenges and the 2024 Reforms

Japan's enforcement regime for TOB and LSR violations has faced criticism for lacking sufficient deterrent effect.

- Current Tools: Enforcement primarily relies on potential criminal penalties (FIEA Art. 197 et seq.) and administrative monetary penalties (kachoukin) (FIEA Art. 172-5 for TOB violations, Art. 172-7 & 172-8 for LSR violations).

- Perceived Weaknesses: The kachoukin amounts (e.g., 25% of acquisition value for TOB violations, a tiny fraction of market cap - 1/100,000 - for LSR reporting failures) are often seen as too low to deter determined violators, especially in high-stakes M&A contexts. Criminal prosecutions are rare.

- Lack of Private Enforcement: Crucially, unlike some jurisdictions, Japanese law generally does not provide target companies or shareholders with a direct private right of action to seek injunctions against TOB or LSR rule violations or to demand corrective disclosure. While administrative orders (e.g., correction orders, emergency cease-and-desist orders by the FSA) exist, their application has been limited.

- WG Discussions vs. Reforms: The Financial System Council WG extensively discussed strengthening enforcement. Proposals included introducing rights for targets/shareholders to seek injunctions and potentially suspending the voting rights of shares acquired or held in violation of TOB/LSR rules. The idea of voting right suspension, in particular, had been debated and ultimately rejected during the 2014 Companies Act revision process due to concerns about proportionality and linking capital market rules directly to company law rights. Despite considerable support within the WG for such measures, the 2024 FIEA amendments did not introduce these new private enforcement mechanisms or voting right suspensions. The focus remained on refining the substantive rules. The WG report did, however, urge authorities to make more proactive use of existing administrative enforcement tools. The practical impact of this encouragement remains to be seen. Recent increases in kachoukin cases for LSR violations suggest a potential shift towards more active administrative enforcement, but the fines remain modest.

3.2. Future Issue: Beneficial Ownership Transparency

Beyond the scope of the LSR (which focuses on direct holdings and joint holders based on agreements), there is an ongoing debate in Japan about the broader transparency of ultimate beneficial owners – the individuals who ultimately own or control shares, often through complex chains of intermediaries or nominee accounts.

- Motivation: The push for greater transparency stems from desires to facilitate more effective shareholder engagement (knowing who the ultimate decision-makers are), combat market abuse (insider trading, manipulation), and align with global trends (e.g., FATF recommendations, EU regulations).

- Current Situation: Outside the LSR context, Japanese companies generally only know the shareholders listed on the shareholder register (kabunushi meibo), which often consists of custodian banks or other nominees, not the end investors. Companies often rely on voluntary or commercial shareholder identification services.

- WG Report & Potential Directions: The WG report acknowledged this as an important issue for future consideration. It contrasted the US approach (public disclosure of institutional holdings via Form 13F) with EU approaches under the Shareholder Rights Directive II (SRD II), which generally grant companies the right to request information about ultimate shareholders from intermediaries. The WG report indicated a preference towards exploring EU-style mechanisms, potentially empowering companies to identify their beneficial owners to facilitate dialogue, rather than broad public disclosure. The report suggested that revisions to the Stewardship Code could be an initial step, potentially encouraging institutional investors to respond to issuer inquiries about their holdings. Subsequent discussions in other forums, including industry groups and government study panels, are exploring legislative options, possibly within future Companies Act reforms. This remains a key area to watch.

Conclusion

The 2024 amendments to Japan's FIEA represent a significant step in modernizing the country's regulatory framework for corporate control transactions and shareholder disclosure. The expansion of mandatory TOB rules to include market purchases closes a long-standing gap, enhancing shareholder protection and market fairness. Refinements to the LSR system attempt to strike a better balance between transparency and facilitating constructive investor-issuer engagement, particularly for institutional investors operating under stewardship principles.

However, challenges remain. The effectiveness of the reforms will depend partly on the details finalized in forthcoming Cabinet Orders and guidelines. More fundamentally, the lack of robust private enforcement mechanisms continues to be a point of concern for some market participants. The broader question of ultimate beneficial ownership transparency also looms as a significant future agenda item.

For international businesses and investors operating in Japan, staying abreast of these regulatory changes and ongoing debates is essential. The 2024 reforms underscore a trend towards greater transparency and shareholder protection in one of the world's major capital markets, requiring careful navigation and strategic adaptation.

- Antitrust Oversight in Japanese M&A: Understanding Merger Control and the Role of Monitoring Trustees

- Platform Power and Antitrust in Japan: Lessons from an Algorithm Change Case

- Derivative vs. Original Acquisition of Rights in Japan: Key Differences for U.S. Investors

- Financial Services Agency — Outline of 2024 FIEA Amendments (JP)

https://www.fsa.go.jp/news/r6/20240522/2024_fiea_amend.html