Navigating "Japan DBS": Background Checks and Employment Law in Child-Related Businesses

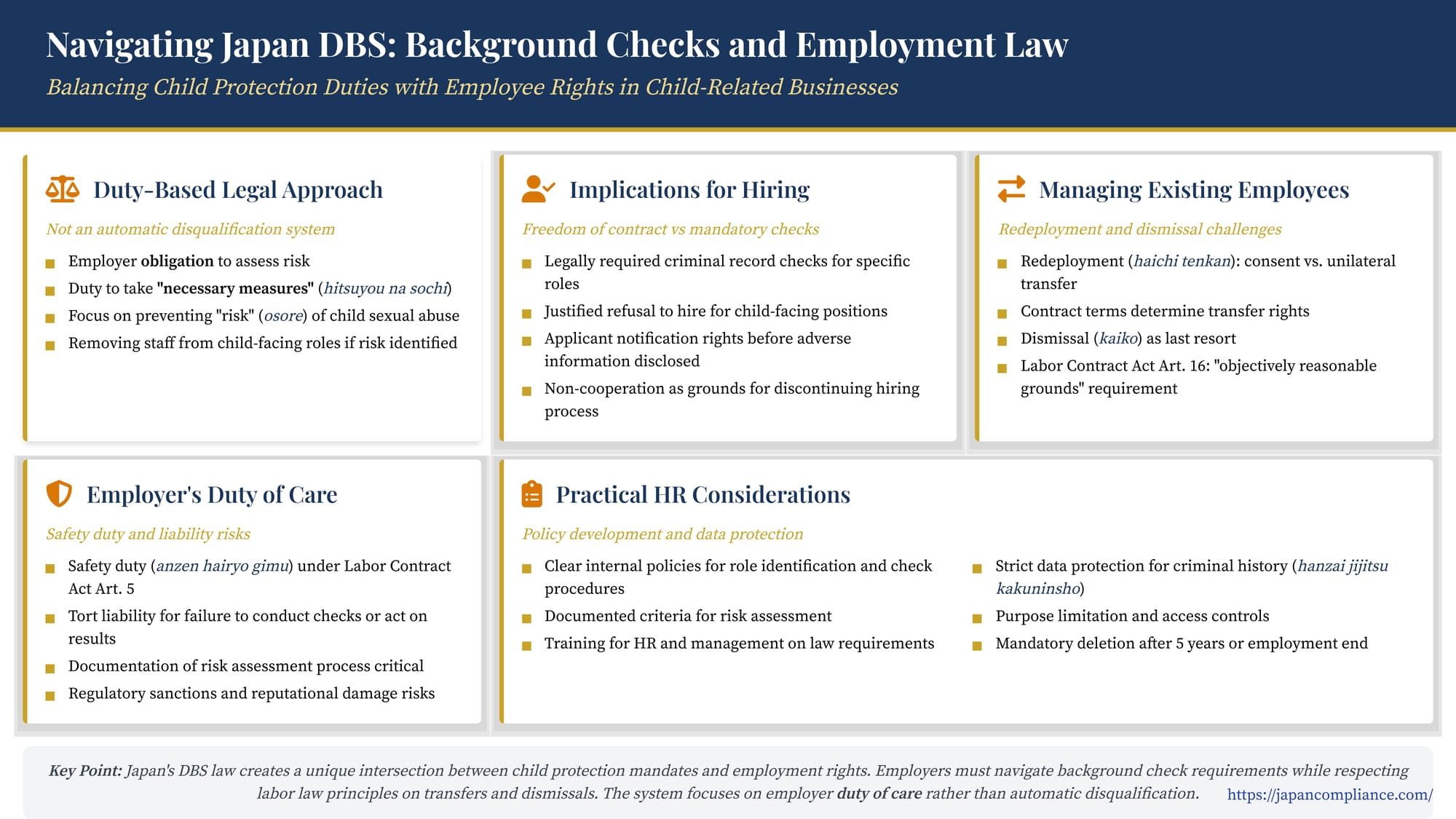

TL;DR: Japan’s DBS Law obliges child-facing businesses to run criminal-record checks and take “necessary measures.” Employers must integrate these checks into hiring, transfers, and dismissals while balancing privacy and strict labor-law protections. Failure to act invites liability and reputational harm.

Table of Contents

- The Legal Framework: A “Duty-Based” Approach

- Implications for Hiring and Recruitment

- Managing Existing Employees: Redeployment and Dismissal Challenges

- Conclusion

Introduction

Conducting background checks is a familiar part of the hiring process in many sectors globally. However, Japan's recent enactment of the "Act on Measures for the Prevention, etc. of Child Sexual Abuse by School Establishments, etc. and Private Education/Childcare Providers, etc." (Act No. 69 of 2024) – commonly known as the "Japanese DBS Law" – introduces a specific, and in some cases mandatory, system for checking the criminal records of individuals working closely with children. While aimed at the crucial goal of enhancing child safety, this law presents significant practical challenges and legal complexities for businesses operating in Japan's education, childcare, and related sectors, particularly concerning human resources (HR) management and employment law.

Unlike systems that might automatically disqualify individuals based on certain convictions, the Japanese DBS Law primarily imposes a duty on employers to conduct checks and then take "necessary measures" based on a risk assessment. This approach creates a unique intersection between child protection mandates and established principles of Japanese labor law regarding hiring, employee privacy, job transfers, and dismissals.

This article delves into the practical HR and labor law implications of the Japanese DBS Law, examining how businesses can navigate the requirements for background checks, manage employees whose records raise concerns, and ensure compliance while respecting employee rights.

1. The Legal Framework: A "Duty-Based" Approach

Understanding the law's structure is key to navigating its employment implications. Unlike traditional Japanese statutes that list specific "disqualification grounds" (kekaku jiyuu) automatically barring individuals with certain convictions from professions like medicine or licensed security work, the DBS law takes a different path.

- Employer Duty (Sekimu, Sochi Gimu): The law mandates that "School Establishments, etc." (schools, nurseries, etc.) and requires that certified "Private Education/Childcare Providers" (like cram schools or sports clubs seeking certification) perform checks using the state system (Articles 4 & 26). Crucially, it then obligates these employers to take "necessary measures" (hitsuyou na sochi) if, based on the check results and other factors, they determine there is a "risk" (osore) of child sexual abuse (Article 6, Article 20).

- No Automatic Disqualification: The law itself does not automatically bar employment based on a conviction. It places the onus on the employer to assess the risk and act accordingly. The primary "necessary measure" mentioned is removing the individual from core child-facing duties.

This "duty-based" model provides some flexibility but also places significant responsibility—and potential liability—on the employer to make appropriate risk assessments and implement measures that comply with both the DBS law and general employment law principles.

2. Implications for Hiring and Recruitment

The most immediate impact of the law is on the hiring process for roles involving direct contact with children.

- Freedom of Contract vs. Mandatory Checks: While employers in Japan generally enjoy "freedom of hiring" (saiyou no jiyuu, derived from constitutional rights like freedom of occupation under Article 22), this freedom is not absolute. The DBS law creates a specific legal obligation for covered employers to conduct checks for relevant roles, overriding general privacy principles that might otherwise limit inquiries into sensitive information like criminal history.

- The Inquiry Right and Obligation: Traditionally, Japanese labor guidelines (e.g., from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare - MHLW) strongly discourage employers from collecting sensitive personal information, including criminal records, unless it is essential for the specific job duties and collected directly from the applicant with clear explanation. The DBS law changes this calculus for covered roles. It provides not just a right but an obligation for covered employers to seek specific criminal history information through the state-administered system. This check is narrowly focused on "Specific Sex Crimes" within defined look-back periods.

- Refusal to Hire: If a prospective employee is flagged by the DBS check as having a relevant conviction, the employer must assess the risk (Article 6). Given the law's explicit purpose of child protection, determining that such a record presents an unacceptable risk for a child-facing role would almost certainly constitute justifiable grounds for refusing to hire for that specific position. This refusal would be based on the statutory duty to prevent harm and the inherent requirements of the job, rather than constituting unlawful discrimination based on criminal history per se. The law essentially defines certain past conduct as directly relevant to suitability for these specific roles.

- Applicant Cooperation and Rights: The DBS check process requires the applicant's cooperation, including providing necessary identification documents (like a copy of the family register - koseki) to the employer for the application (Article 33, Paragraph 5). Importantly, applicants have the right to be notified by the authorities before adverse information is sent to the employer and the right to request correction if they believe the information is inaccurate (Articles 35 & 37). An applicant's refusal to cooperate with the check would likely be legitimate grounds for the employer to discontinue the hiring process for a covered role.

3. Managing Existing Employees: Redeployment and Dismissal Challenges

Perhaps the most complex employment law issues arise when checks are conducted on existing employees, either during the initial implementation phase (Article 4, Paragraph 3) or through periodic re-checks (Article 4, Paragraph 4).

- The Duty to Take "Necessary Measures": If a check reveals that a current employee is a "Person Corresponding to Specific Sex Crime Facts," the employer's duty under Article 6 (or equivalent internal rules for certified providers under Art. 20) is triggered. The employer must assess the risk and implement "necessary measures," explicitly including removal from core child-facing duties.

- Redeployment (Haichi Tenkan) as a Primary Measure: Logically, the least disruptive "necessary measure" is often transferring the employee to a position that does not involve contact with children. However, the legal basis for such a transfer requires careful consideration under Japanese labor law:

- Employee Consent: The simplest path is obtaining the employee's agreement to the transfer.

- Unilateral Transfer: If consent is not given, the employer's right to unilaterally order a transfer depends on the employment contract and established case law (e.g., the Toa Paint decision, Supreme Court, July 14, 1986). Generally, unilateral transfers are permissible only if:

- The employment contract or work rules (shuugyou kisoku) contain a provision allowing for transfers (often a broad clause permitting changes in job duties or location). Specific agreements limiting the job scope (shokushu gentei goui) would preclude unilateral transfers outside that scope.

- The transfer order does not constitute an "abuse of rights" (kenri ranyou). This involves assessing the business necessity of the transfer against the detriment to the employee (considering factors like impact on career, family life, etc.).

- The DBS Law's Role: Critically, legal analysis suggests the DBS law itself likely does not create an independent right for the employer to unilaterally transfer an employee against their will or contractual agreement. The law mandates that the employer take necessary measures, but how those measures are implemented must generally comply with existing labor contract principles.

- Practical Difficulties: Even if contractually permissible, finding a suitable non-child-facing role within the organization may be difficult, especially in smaller businesses or specialized institutions. Wage implications of a transfer to a different role also need consideration.

- Dismissal (Kaiko) as a Last Resort: If redeployment is not contractually possible, if no suitable alternative role exists, or if the employee refuses a legitimate transfer offer, the employer may consider dismissal. This, however, engages Japan's robust dismissal protections under Article 16 of the Labor Contract Act, which requires dismissals to have "objectively reasonable grounds" (kyakkanteki ni gouriteki na riyuu) and be "socially acceptable" (shakai tsuunen jou soutou).

- Objective Reasonable Grounds: Would a relevant conviction revealed by a DBS check constitute objectively reasonable grounds for dismissal from a child-facing role? Given the law's explicit purpose, the employer's statutory duty under Article 6, and the high standard of care required when working with children, it is highly probable that such a conviction would be seen as fundamentally undermining the employee's suitability for that specific type of work. The inability to perform the core, child-facing duties due to the legally mandated risk assessment likely provides an objective basis.

- Social Acceptability: This involves proportionality. If redeployment is genuinely impossible, dismissal might be considered socially acceptable to fulfill the employer's child protection duty. However, factors like the nature and age of the conviction, evidence of rehabilitation, the employee's work record, and the specific risks associated with the role would likely be relevant in a legal challenge. Dismissal should be the measure of last resort after exploring all feasible alternatives. Future case law will be critical in defining the boundaries here.

- Procedural Fairness: Any dismissal process must adhere to procedural fairness requirements outlined in work rules or collective agreements.

4. Employer's Duty of Care and Liability

The DBS law adds a specific layer to the employer's general duty of care.

- Safety Duty (Anzen Hairyo Gimu): Under Article 5 of the Labor Contract Act, employers have a duty to ensure a safe working environment for their employees. In the context of child-related services, this duty implicitly extends to ensuring the safety of the children under their care. The DBS law makes specific aspects of this duty explicit – namely, the obligation to screen relevant staff and manage identified risks.

- Liability for Failure to Act: Employers who fail to conduct the required checks, ignore the results, or fail to implement "necessary measures" after identifying a risk face significant legal exposure if a child is subsequently abused by that employee. Potential liabilities include:

- Tort claims from the victim/family under the Civil Code (Art. 709 for direct negligence, potentially Art. 715 for employer liability).

- Claims for breach of the safety duty or employment contract.

- Regulatory sanctions from the CFA, including public naming or loss of certification for private providers.

- Irreparable damage to the organization's reputation.

Thorough documentation of the risk assessment process, the rationale for decisions made (whether reassignment, dismissal, or continued employment in a non-contact role), and the specific measures taken is crucial for demonstrating compliance and mitigating liability risks.

5. Practical HR Considerations and Data Management

Implementing the DBS law requires careful planning and integration into HR systems:

- Policy Development: Businesses need clear, documented internal policies covering:

- Which roles require DBS checks.

- The procedure for conducting checks (including obtaining applicant/employee cooperation and handling documentation).

- Criteria and process for assessing risk if a relevant record is found.

- Procedures for implementing necessary measures (redeployment options, dismissal protocols).

- Strict protocols for managing, storing, accessing, and deleting sensitive CRC data in compliance with both the DBS law and Japan's Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI).

- Training: HR personnel, managers involved in hiring and supervision, and potentially all staff need training on the law's requirements, internal procedures, confidentiality obligations, and broader child protection principles.

- Data Protection: The handling of CRC information (hanzai jijitsu kakuninsho) demands the highest level of data security and privacy compliance. Key requirements include:

- Strict purpose limitation (use only for DBS risk assessment).

- Access control (limiting who can see the information).

- Secure storage.

- Timely and documented deletion (Article 38 mandates deletion after specified periods, generally 5 years post-check or earlier if employment ceases/doesn't commence).

- Awareness of penalties for breaches (Articles 43-46 impose significant criminal penalties for unauthorized disclosure or misuse).

Conclusion

Japan's new DBS law introduces a significant regulatory requirement with profound implications for employment practices in organizations serving children. The law's "duty-based" approach, compelling employers to check specific criminal records and act on identified risks, intersects directly with established Japanese labor law principles governing hiring, privacy, transfers, and dismissals.

For HR and legal professionals in covered businesses, navigating this landscape requires more than just procedural compliance with the checks themselves. It demands the development of robust internal policies, careful risk assessment protocols, secure data management practices, and a nuanced understanding of how to implement "necessary measures" – including potential redeployment or dismissal – in a way that respects both the child protection mandate and employee rights under Japanese labor law.

Given the complexities, particularly in managing existing employees flagged by checks, seeking expert legal counsel is highly advisable. As the system operates and potentially faces legal challenges, case law and further regulatory guidance will be essential in clarifying the practical application of these intersecting legal duties. Proactive planning and a commitment to both child safety and fair employment practices will be key for businesses successfully adapting to this new regulatory environment.