Navigating Inheritance and Debt: Japanese Supreme Court Clarifies Enforcement Against Jointly Inherited Book-Entry Securities

Date of Judgment: January 23, 2019

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

In an increasingly digital financial world, the nature of asset ownership and transfer has evolved significantly. Japan, like many other nations, utilizes a book-entry system for the transfer and holding of shares and other securities. This system, governed by the Act on Book-Entry Transfer of Corporate Bonds, Shares, etc. (hereinafter, the "Book-Entry Transfer Act"), streamlines transactions but can also present unique challenges, particularly in situations involving inheritance and debt enforcement.

A key characteristic of the book-entry system is that the rights of security holders are determined by entries in accounts maintained by account management institutions (AMIs). This typically simplifies the determination of ownership. However, complications arise when these book-entry securities are inherited, especially when they become the joint property of multiple heirs, one of whom may be a debtor.

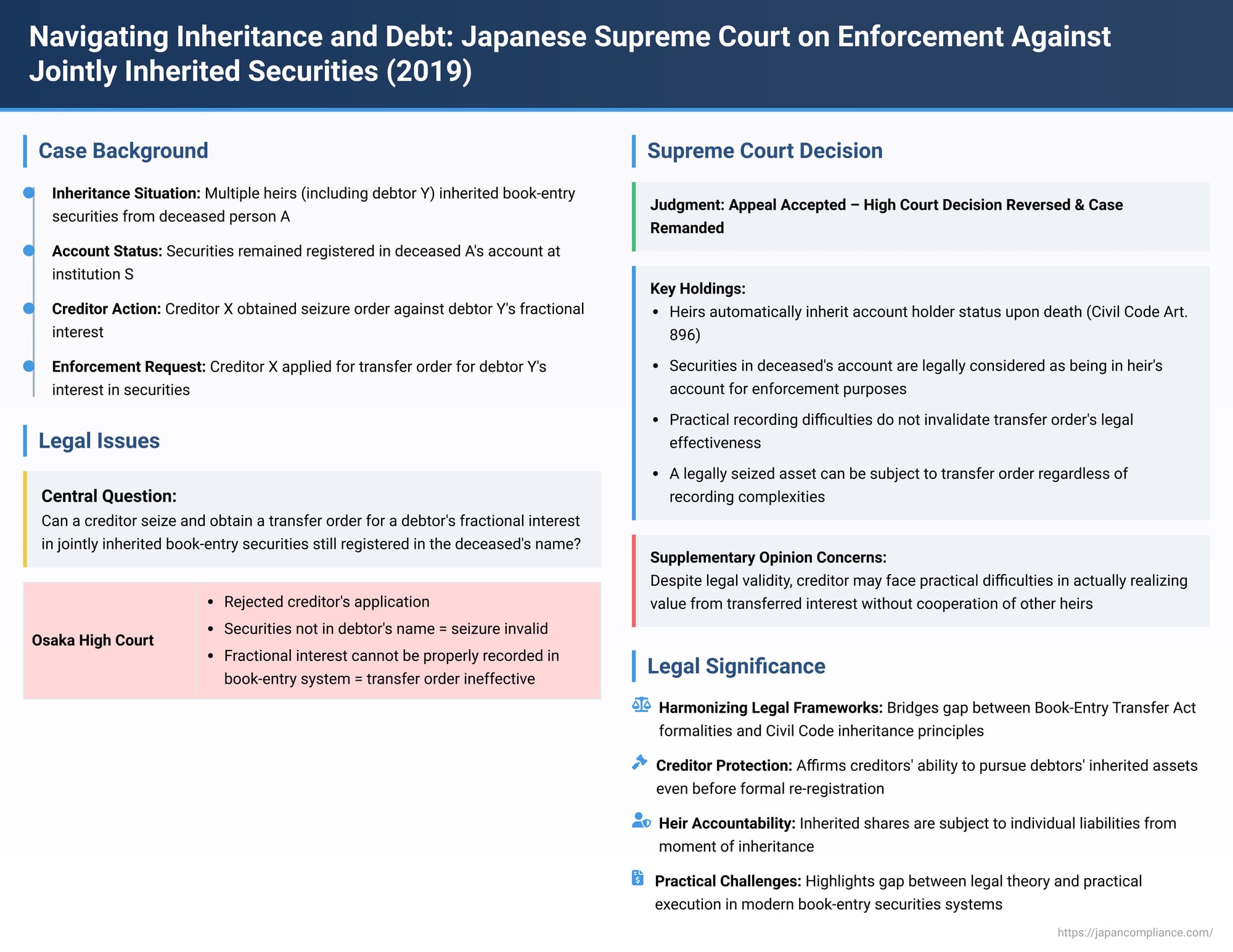

This was precisely the scenario addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in its significant decision on January 23, 2019. The case explored whether a creditor could effectively seize and obtain a transfer order for a debtor’s fractional interest in jointly inherited book-entry securities when those securities were still registered in an account under the deceased's name, and when practical difficulties existed in registering the debtor's isolated fractional interest.

This article will delve into the specifics of this Supreme Court judgment, examining the facts, the lower court's initial stance, the Supreme Court's definitive reasoning, and the broader implications for creditors, heirs, and financial institutions in Japan.

Background of the Dispute

The case revolved around a creditor, whom we will refer to as X, seeking to recover a debt from an individual, Y. Y, along with four other individuals, had jointly inherited a portfolio of assets from a deceased person, A. These assets included shares, investment trust beneficiary rights, and investment units (collectively referred to as "book-entry securities"). These securities were held in an account at S, an account management institution, and importantly, this account remained in the name of the deceased, A.

X, the creditor, identified Y's inherited fractional interest in these book-entry securities as a potential asset to satisfy the outstanding debt. Consequently, X initiated legal proceedings and successfully obtained a seizure order (a court order freezing the asset to prevent its disposal) against Y's fractional interest in the securities held in A's account.

Following the seizure, X took the next logical step in the enforcement process: applying to the court for a transfer order. A transfer order, in this context, is a judicial directive that effectively transfers ownership of the seized asset (in this case, Y’s fractional share of the securities) to the creditor in satisfaction of the debt, up to the value determined by the court.

The central issue was whether such a transfer order could be lawfully issued and practically effective given the circumstances: the securities were in an account under the deceased’s name, and the asset in question was merely a fractional co-ownership interest.

The High Court's Position: A Roadblock for the Creditor

The Osaka High Court, which heard the case prior to the Supreme Court appeal (referred to as the "lower court" or "original instance court" in the Supreme Court's judgment), ruled against the creditor, X. It rejected X’s application for a transfer order based on two primary lines of reasoning:

- Illegality of the Seizure due to Account Name: The High Court emphasized that under the Book-Entry Transfer Act, the rights pertaining to book-entry securities are determined by the records in the book-entry account. It reasoned that for enforcement proceedings, the court must verify the debtor's ownership based on these records. Since the account holding the securities was in the name of A (the deceased), not Y (the debtor), the High Court concluded that a seizure order could not be validly issued against securities in an account not registered in the debtor's name. Consequently, if the initial seizure order was deemed illegal, any subsequent application for a transfer order based on that seizure would also be unlawful.

- Ineffectiveness of a Transfer Order for a Fractional Interest: The High Court further opined on the nature of jointly inherited book-entry securities. It acknowledged that such securities could be recorded in an account under the names of all co-heirs jointly. However, it asserted that it was not possible to record a single co-heir's individual fractional interest in that co-heir's separate account. Therefore, even if a transfer order for Y's fractional interest were to be confirmed, it could not actually effect a transfer of ownership in a way that could be properly recorded or recognized by the book-entry system. This perceived impossibility of effectuating the transfer led the High Court to deem the application for a transfer order itself as unlawful.

The High Court's decision, if upheld, would have posed a significant hurdle for creditors seeking to enforce debts against inherited fractional interests in book-entry securities, especially in the common scenario where estate administration might not have progressed to the point of re-registering assets into individual heirs' names.

The Supreme Court's Reversal: Clarifying Inheritance and Enforcement

The creditor, X, appealed the High Court's decision to the Supreme Court of Japan. On January 23, 2019, the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, decisively overturning the High Court's conclusions and remanding the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court found both of the High Court's primary arguments to be unsupportable.

1. Succession to Account Holder Status and the Validity of Seizure

The Supreme Court first addressed the High Court's finding that the seizure order was illegal because the account was in the deceased's name.

- Automatic Succession under Civil Code: The Court began by referencing a fundamental principle of Japanese inheritance law (Article 896 of the Civil Code), which states that heirs succeed to all rights and duties pertaining to the deceased's property from the moment of death, unless otherwise specified. This principle applies to book-entry securities just as it does to other assets.

- Inheritance of Account Holder Status: Crucially, the Supreme Court extended this principle to the deceased's status as an account holder with the AMI. It reasoned that when heirs inherit book-entry securities, they also inherit the deceased's position and rights as the individual who established and maintained the account where those securities are recorded.

- Deceased's Account Deemed Heir's Account: Based on this, the Supreme Court concluded that book-entry securities recorded in an account under the deceased’s name can be considered, for legal purposes, as being recorded in the heir's account. This applies even in cases of joint inheritance where multiple heirs collectively succeed to this status.

- Seizure Order Upheld: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that a seizure order against a debtor-heir's fractional interest in jointly inherited book-entry securities is not illegal merely because the account remains in the deceased's name. The underlying beneficial ownership and the inherited status as account holder provide a sufficient basis for such an enforcement action.

This reasoning effectively harmonized the provisions of the Book-Entry Transfer Act (which emphasizes the importance of account records) with the overarching principles of inheritance law. It recognized that while formal re-registration is an administrative step, the substantive rights of heirs are established at the moment of inheritance.

2. Validity of the Transfer Order Despite Recording Complexities

Next, the Supreme Court tackled the High Court's assertion that a transfer order could not be issued because a single co-heir's fractional interest could not be separately recorded in their individual account, rendering the transfer ineffective.

- Recording Difficulties Do Not Equal Ineffectiveness: The Supreme Court stated that the inability to record a single co-heir's fractional interest in their name in a separate account does not inherently mean that a transfer order for that interest is legally void or that the transfer itself cannot take effect.

- No Legal Prohibition on Transfer Orders for Fractional Interests: The Court found no legal basis for the proposition that a court cannot issue a transfer order for an asset that has been lawfully seized, solely because that asset is a fractional interest in book-entry securities. As long as the transfer of the asset is not legally prohibited and it is a valid object of a seizure order, a transfer order can, in principle, be issued.

- Focus on Substantive Rights Transfer: The essence of a transfer order is the transfer of substantive ownership rights. While the subsequent administrative steps of recording that transfer are important for practical purposes and third-party dealings, any difficulties in that recording process do not retroactively invalidate the judicial order itself.

Thus, the Supreme Court concluded that an application for a transfer order concerning a debtor's fractional interest in jointly inherited book-entry securities cannot be dismissed outright simply because of the nature of that interest or the current state of its registration.

The Supreme Court found that the High Court's decision contained errors in the interpretation and application of the law that clearly affected the judgment. It therefore quashed the High Court's ruling and sent the case back to the Osaka High Court for reconsideration in light of the Supreme Court's clarifications.

Deeper Dive: Rationale, Implications, and Practical Realities

The Supreme Court's decision provides crucial clarity on the interplay between the book-entry securities system, inheritance law, and debt enforcement procedures in Japan.

Harmonizing Legal Frameworks: The judgment effectively bridges a potential gap between the formal requirements of the Book-Entry Transfer Act, which prioritizes the information in the securities register, and the substantive effects of Japan's Civil Code concerning inheritance, which dictates automatic and comprehensive succession of property rights. The Court affirmed that the inherited rights are paramount and can be acted upon even if administrative formalities (like re-registering the account) are pending.

Significance for Creditors: For creditors, this ruling is generally favorable. It reinforces their ability to pursue a debtor's assets even when those assets are fractional interests in jointly inherited book-entry securities held in a decedent's account. This prevents debtors from potentially shielding assets by delaying the re-registration of inherited securities.

Implications for Heirs and Estate Management: For heirs, the decision underscores that their inherited shares in book-entry securities are subject to their individual liabilities from the moment of inheritance. It also implicitly encourages timely administration of estates, including the proper registration and distribution of inherited assets, to avoid complications arising from the debts of individual co-heirs.

Challenges in Practical Execution: While the Supreme Court affirmed the legality of issuing a transfer order in such situations, it did not, in its main opinion, delve deeply into the practical methods by which a creditor would subsequently realize the value of the transferred fractional interest. This practical aspect was, however, addressed in a supplementary opinion by one of the Justices, which, while not binding in the same way as the main judgment, offered valuable insights into the remaining challenges and potential pathways.

The supplementary opinion acknowledged that simply obtaining a transfer order for a fractional interest in book-entry securities doesn't automatically mean the creditor can easily convert that interest into cash or gain full, uncomplicated control over it. Specific challenges highlighted included:

- Difficulty in Isolating and Registering Fractional Interests: The core problem remained that account management institutions (AMIs) may not have procedures to record or manage isolated fractional interests of a single co-owner in their individual name. The system is generally designed around whole units of securities or jointly owned accounts.

- Potential for a "Joint Account" Solution: One theoretical solution mooted was the possibility of the creditor (now a co-owner by virtue of the transfer order) and the other original co-heirs (excluding the debtor) jointly opening a new "co-ownership account." The entirety of the jointly owned securities (including the portion now belonging to the creditor) could then be transferred from the deceased's account to this new joint account. This would at least reflect the creditor's status as a co-owner in the book-entry system.

- Obstacles to the Joint Account Solution: This approach, however, faces its own hurdles.

- AMI Practices: AMIs may not routinely offer or support the opening of such co-ownership accounts for book-entry securities, especially involving a creditor who has become a co-owner through an enforcement action.

- Cooperation of Other Heirs: This method would almost certainly require the active cooperation of the other co-heirs. If they are uncooperative, the creditor might be unable to compel the opening of such an account or the transfer of the securities.

- The Creditor's Risk: A significant concern raised was that under Japanese civil execution rules (specifically, Article 160 of the Civil Execution Act, referenced via a procedural rule for transfer orders), when a transfer order is served on the relevant third party (here, the AMI S), the creditor's claim against the debtor is deemed satisfied up to the value assigned to the transferred asset by the court. If the creditor then faces practical difficulties in actually liquidating or benefiting from that fractional interest, they bear that risk. This outcome seems contrary to the principle that a creditor enforcing a legitimate claim against legally seizable assets should not be unduly hampered by systemic procedural limitations.

- The Need for Systemic Improvements: The supplementary opinion suggested that, ideally, there should be clearer legal or operational frameworks enabling AMIs to facilitate the realization of rights from such transfer orders without necessarily depending on the consent or cooperation of all other co-owners. This might involve AMIs being more prepared to handle co-ownership accounts or having clearer procedures for dealing with judicially transferred fractional interests.

- The Partition Remedy: In the absence of smoother systemic solutions, the supplementary opinion pointed to a more traditional, albeit potentially more cumbersome, path for the creditor: after the transfer order is finalized, the creditor, as a new co-owner of the securities, could initiate a legal action for the partition of co-owned property (kyōyūbutsu bunkatsu). This is a standard legal procedure for dividing jointly owned assets. Through a partition action, the creditor could seek to have their fractional interest physically or monetarily separated from that of the other co-owners, thereby realizing its value. The fact that this possibility of partition exists further supports the Supreme Court's main finding that the initial application for a transfer order is not inherently unlawful.

Conclusion

The Japanese Supreme Court's decision of January 23, 2019, provides vital clarification on the enforcement of debts against fractional interests in jointly inherited book-entry securities. By confirming that heirs also succeed to the deceased's status as an account holder and that practical recording difficulties do not invalidate a transfer order, the Court has affirmed a pathway for creditors.

The judgment underscores that substantive inheritance rights can form the basis for enforcement actions, even if administrative re-registration of assets has not yet occurred. However, the insights from the supplementary opinion also serve as a crucial reminder that legal victory in obtaining a transfer order does not always translate into immediate and straightforward practical recovery. Creditors may still face procedural complexities in liquidating or isolating the value of such fractional interests, potentially needing to resort to further legal actions like a partition of property.

Ultimately, this decision navigates the complex intersection of modern financial systems, traditional inheritance principles, and the imperative of effective debt enforcement, highlighting areas where legal interpretation can provide clarity and also where operational practices might need to evolve to better support legal realities.