Employee Dismissals in Japan: Membership vs. Job-Based Models and Termination Rules

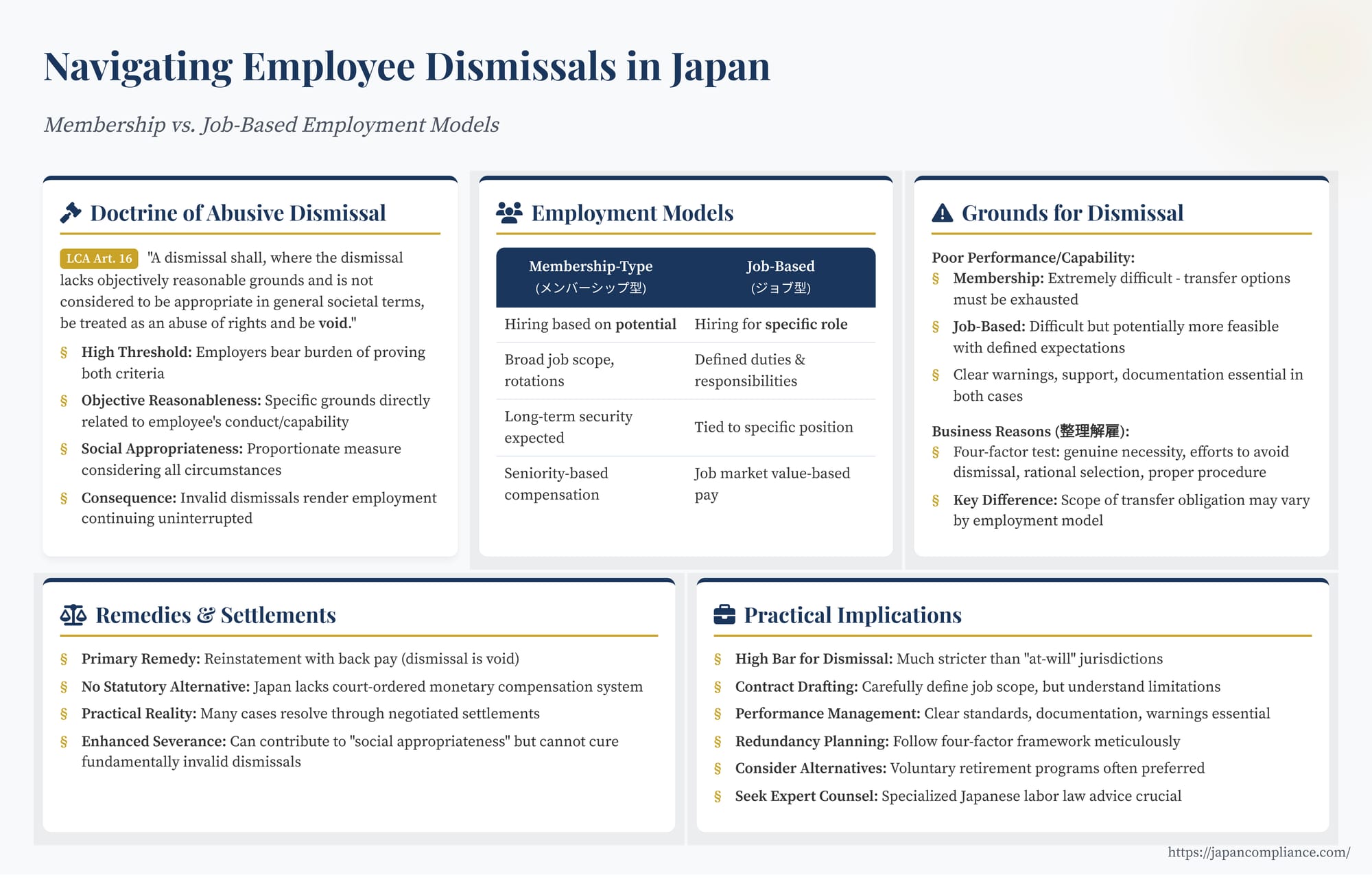

TL;DR: Japan’s “membership” employment model makes dismissals difficult: employers must satisfy the four-factor abusive-dismissal test. Job-based contracts allow clearer exit routes but still face strict notice or severance rules. Documented performance management is critical.

Table of Contents

- The Doctrine of Abusive Dismissal (LCA Art. 16)

- “Membership” vs. “Job-Based” Employment Models

- Grounds for Dismissal: Judicial Scrutiny

- Remedies: Reinstatement or Monetary Settlements

- Labor-Market Policy Perspective

- Practical Implications for Foreign Employers

- Conclusion: Navigating Japan’s High-Protection Regime

For international businesses operating in Japan, managing human resources effectively requires a deep understanding of the country's unique labor law landscape. One of the most critical, and often challenging, areas is employee dismissal (kaiko - 解雇). Unlike the "employment-at-will" doctrine prevalent in many parts of the United States, Japanese law provides robust protection against termination, rooted in case law and codified in the Labor Contract Act (LCA). Simply providing notice or severance pay is often insufficient; dismissals require objective justification and must meet stringent standards of social appropriateness.

Furthermore, the prevailing employment models in Japan – the traditional, relationship-focused "membership-type" system versus the increasingly discussed (though less widespread) "job-type" system – add layers of complexity to how dismissal regulations are applied. This article explores the core principles governing employee dismissals in Japan, focusing on the doctrine of abusive dismissal, how it interacts with different employment models, and key considerations for businesses navigating terminations.

The Foundation: The Doctrine of Abusive Dismissal (LCA Art. 16)

While Japan's Civil Code (Art. 627) allows either party in an indefinite-term employment contract to terminate with notice (typically two weeks for the employee), this theoretical "freedom of dismissal" (kaiko jiyū) for employers is heavily restricted by the doctrine of abusive dismissal (kaikoken ran'yō hōri - 解雇権濫用法理). This doctrine, developed through decades of court precedent and formally codified in Article 16 of the Labor Contract Act, states:

"A dismissal shall, where the dismissal lacks objectively reasonable grounds and is not considered to be appropriate in general societal terms, be treated as an abuse of rights and be void."

Key takeaways from this provision:

- High Threshold: Dismissals are permitted only under limited circumstances. The employer bears the significant burden of proving both objective reasonableness and social appropriateness.

- Objective Reasonableness (kyakkanteki ni gōriteki na riyū): Requires concrete, specific grounds directly related to the employee's conduct, capability, or demonstrable business necessity (e.g., severe misconduct, persistent and irremediable poor performance after warnings and support, genuine need for workforce reduction). Vague justifications are insufficient.

- Social Appropriateness (shakai tsūnenjō sōtō): Even if reasonable grounds exist, the dismissal must also be considered a proportionate and fair measure in light of all circumstances. This involves assessing factors like the severity of the employee's conduct/shortfall, the employer's efforts to avoid dismissal (warnings, training, transfers), the impact on the employee, and standard practices in the industry or society.

- Consequence: Invalidity (Mukō): If a dismissal fails either prong of the test, it is legally void. This means the employment relationship is deemed to have continued uninterrupted. The primary remedy is reinstatement to the former position with back pay for the period since the purported dismissal.

"Membership" vs. "Job-Based" Employment: Does it Matter for Dismissals?

Understanding how LCA Article 16 applies often involves considering the nature of the employment relationship, typically categorized into two broad, albeit sometimes overlapping, models:

- "Membership-Type" Employment (Menbāshippu-gata Koyō): This has been the dominant model for "regular" employees (seishain) in larger Japanese companies. Key characteristics include:

- Hiring typically occurs straight from school based on general potential, not a specific job opening.

- Broad job scope: Employees are considered members of the corporate organization first, with specific duties and work locations subject to change via employer orders (transfers, rotations).

- Implicit long-term employment security, often until mandatory retirement age.

- Compensation often based on seniority and internal equity rather than purely market rates for a specific job.

- "Job-Type" Employment (Jobu-gata Koyō): This model, closer to practices common in the US and Europe, involves hiring individuals for specific roles with defined duties, responsibilities, and potentially work locations clearly outlined in the employment contract.

- Compensation is often tied more directly to the specific job's market value and performance within that role.

- Flexibility in job assignments and transfers is more limited by the contractual definition of the job.

- While gaining attention and being promoted as part of labor market reforms, this model is still less prevalent overall than the membership model, though common in certain industries or for specialized roles.

Why does this distinction matter for dismissals? Because the underlying assumptions about the employment relationship influence the assessment of "objective reasonableness" and "social appropriateness" under LCA Art. 16.

Grounds for Dismissal: Judicial Scrutiny in Practice

Let's examine how courts approach common dismissal scenarios in light of these models:

A) Dismissal for Cause (Poor Performance, Lack of Capability):

- In a "Membership" Context: Dismissing a regular employee solely for underperformance in their current role is notoriously difficult. Courts generally expect the employer to demonstrate that:

- The underperformance is significant and persistent.

- The employee received clear warnings and concrete feedback.

- Adequate training, support, and opportunities for improvement were provided.

- Crucially, transfer to a potentially more suitable position within the company was considered and attempted if feasible. The assumption is that a "member" might contribute effectively elsewhere in the organization. Only if improvement efforts fail and no suitable alternative role exists might dismissal become justifiable. (e.g., Sega Enterprises case; Morishita Jintan case - anonymized references to cases illustrating the point).

- In a "Job-Based" Context: If an employee is hired for a specific role with clearly defined duties and necessary qualifications stated in the contract, the legal analysis may differ slightly.

- If the employee demonstrably lacks the core skills essential for that specific job and cannot perform the defined duties despite reasonable support and warnings, the argument for dismissal might be stronger. The employer's obligation to consider transfers could be interpreted more narrowly if the contract truly limits the employee's scope to that specific job.

- However, the abusive dismissal doctrine still applies. Courts will still scrutinize whether the performance standard was clear, whether the employee was given a fair chance, and whether dismissal is a proportionate response. Japanese courts remain generally reluctant to uphold performance-based dismissals without substantial evidence of persistent, significant failure and exhausted remediation efforts, even in roles with defined scopes. Cases upholding such dismissals often involve highly specialized roles with clearly articulated and critical performance expectations that were demonstrably unmet (e.g., Ford Japan case; Proudfoot Japan case - anonymized references).

B) Dismissal for Business Reasons (Redundancy / Seiri Kaiko):

This type of dismissal, driven by economic downturns, restructuring, or business closures, is also strictly regulated under LCA Art. 16. Courts typically evaluate the validity of redundancy dismissals (seiri kaiko - 整理解雇) using a well-established "four-factor" framework:

- Necessity for Workforce Reduction: Is there a genuine, significant business need for layoffs? The employer must demonstrate financial difficulties or structural changes necessitating personnel cuts.

- Efforts to Avoid Dismissal: Did the employer make sufficient efforts to avoid compulsory redundancies? This is a critical factor. Courts expect employers to explore and implement alternatives such as:

- Hiring freezes

- Restrictions on overtime

- Reduction of executive compensation

- Transfers (haiten) and secondments (shukkō) to other departments or affiliated companies

- Soliciting voluntary retirements (kibō taishoku) or offering early retirement packages.

Only when these alternatives are exhausted or insufficient may compulsory dismissal be considered.

- Rationality of Selection Criteria: Were the criteria used to select employees for dismissal objective, fair, and consistently applied? Discriminatory or arbitrary selection is impermissible. Factors like performance evaluations, skills, and attendance records may be considered, but criteria must be clear and applied non-arbitrarily.

- Procedural Appropriateness: Did the employer provide adequate explanation to and engage in sufficient consultation with the affected employees and/or their labor union regarding the necessity of the redundancies, the timing, the scale, and the selection criteria? Transparent communication and genuine consultation are required.

- Impact of Job Scope Limitation on Factor (2): The "efforts to avoid dismissal" factor is where the employment model becomes particularly relevant in redundancy scenarios.

- For a "membership-type" employee with broad potential assignments, the employer's duty to explore transfers to any potentially suitable vacant position within the company (or even affiliates) is generally considered extensive.

- For a "job-type" employee hired for a specific, limited role that is being eliminated, the scope of the employer's obligation to find an alternative position might be narrower. Some case law suggests that if the contract genuinely limits the role, the employer's duty focuses primarily on vacancies within that defined area of expertise or function. However, some effort to find alternatives is still generally expected. Cases allowing dismissal more readily often involve highly specialized positions where redeployment options are genuinely limited (illustrative references like the Kadokawa Culture Promotion Foundation situation; Credit Suisse Securities situation; Faith situation - anonymized).

- Consideration of Mitigation Measures: Some court decisions indicate that providing enhanced severance packages, outplacement assistance, or extended notice periods beyond the statutory minimum, while not substituting for the four factors, can be considered positively within the overall assessment of "social appropriateness" (Factor 4 or the final balancing). Such measures demonstrate the employer's efforts to cushion the blow of dismissal. However, a generous package cannot cure a dismissal that fundamentally fails one of the other core requirements (illustrative reference like the Nihon Tsushin situation; Daisho Tokushukai Gakuen situation).

Remedies: Reinstatement vs. Monetary Solutions

As stated, the primary legal effect of an abusive dismissal finding under LCA Art. 16 is that the dismissal is void. This means:

- Reinstatement: The employee is legally entitled to return to their position.

- Back Pay: The employer must pay wages for the entire period from the date of the invalid dismissal until reinstatement (or settlement).

While reinstatement is the default legal remedy, in practice, many dismissal disputes are resolved through monetary settlements negotiated during court proceedings or through labor tribunal mediation. The employment relationship has often broken down, making a return to the workplace impractical for both sides.

However, unlike some other countries, Japan does not have a generally applicable statutory system allowing courts to order monetary compensation (kinsen kaiketsu) as an alternative remedy if reinstatement is deemed inappropriate or impractical, despite years of policy debate. Discussions around introducing such a system (often focusing on employee-initiated claims as an option) have occurred periodically since the early 2000s, driven by arguments that it could provide faster and more realistic resolutions. However, strong opposition from labor unions concerned about undermining employment security, coupled with complex legal and technical challenges, has meant that legislative proposals have stalled. Currently, monetary resolution remains primarily a matter of voluntary settlement.

A Broader Perspective: Labor Market Policy Considerations

Viewing dismissal regulation within the wider labor market context offers additional insights. Traditionally, Japanese dismissal law has strongly prioritized stability within a specific company (koyō no antei). However, in an era promoting greater labor mobility and reskilling, some argue for policies that better support shokugyō no antei – the ability of workers to maintain stable careers and employment within their chosen occupation or field, even if it involves moving between employers. Overly rigid dismissal rules might inadvertently hinder this broader occupational stability by discouraging companies from hiring regular employees or adapting quickly to market changes.

Furthermore, the current system places the primary cost burden of employment termination (severance, back pay in case of invalid dismissal) on the individual employer. Alternative perspectives suggest that some of these costs, particularly those related to supporting displaced workers' transitions (unemployment benefits, retraining programs), could be more effectively borne by broader social insurance systems or government labor market programs, potentially reducing employer resistance to necessary workforce adjustments while still providing worker support. A potential benefit of a clearer shift towards job-based employment structures (if accompanied by adapted legal interpretations) could also be increased predictability for both employers and employees regarding performance expectations and the circumstances under which termination might be permissible.

Practical Implications for Foreign Employers in Japan

Navigating terminations in Japan requires careful planning and adherence to legal standards:

- High Bar for Dismissal: Emphasize that terminating employees in Japan is significantly more difficult than in "at-will" jurisdictions. Thorough documentation, objective grounds, procedural fairness, and exploration of alternatives are critical.

- Contract Drafting: Consider the implications of defining job scope narrowly ("job-type") versus broadly ("membership-type") in employment agreements, understanding it may influence (but not eliminate) dismissal standards. The 2024 revision to the Labor Standards Act Enforcement Regulations requiring clearer indication of the scope of potential changes in duties/location upon hiring adds importance to this.

- Performance Management: Implement clear performance standards, provide regular feedback, document performance issues, offer training/improvement plans, and issue formal warnings before considering dismissal for capability reasons.

- Redundancy Planning: If workforce reductions are necessary, carefully follow the four-factor framework, documenting the business need, exploring all feasible alternatives (including voluntary retirement programs), using fair selection criteria, and consulting appropriately. Consider offering mitigation measures.

- Legal Advice: Stress the importance of seeking experienced Japanese labor law counsel before taking any termination action.

Conclusion: High Protection Requires Careful Navigation

Japan's legal framework offers employees significant protection against dismissal through the doctrine of abusive dismissal codified in LCA Article 16. Employers must demonstrate objectively reasonable grounds and social appropriateness for any termination, facing the primary remedy of reinstatement and back pay if they fail to meet this high standard. While the nuances of traditional "membership-type" versus emerging "job-based" employment models can influence the judicial assessment, particularly regarding redundancy dismissals, the core principles of justification and proportionality apply across the board.

Although discussions about labor market reforms and alternative remedies like statutory monetary compensation continue, the current reality for businesses operating in Japan is that employee dismissals require exceptional justification, meticulous process, and a thorough exploration of alternatives. Proactive human resource management, clear documentation, and expert legal counsel are essential for navigating this complex area of Japanese employment law.

- Mind the Gap: Wage Disparity Between Fixed-Term and Indefinite-Term Employees

- Engaging Japan’s Freelance Workforce: The New Freelance Protection Act

- Post-Employment Non-Competes in Japan: Legal Tests & Drafting Tips

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare — Q&A on Dismissal and Non-Renewal

https://www.mhlw.go.jp/stf/seisakunitsuite/bunya/roudoukijun/roudoukijun/taishoku.html