Director Liability Under Japan’s Companies Act – How to Handle Conflict-of-Interest Deals

TL;DR

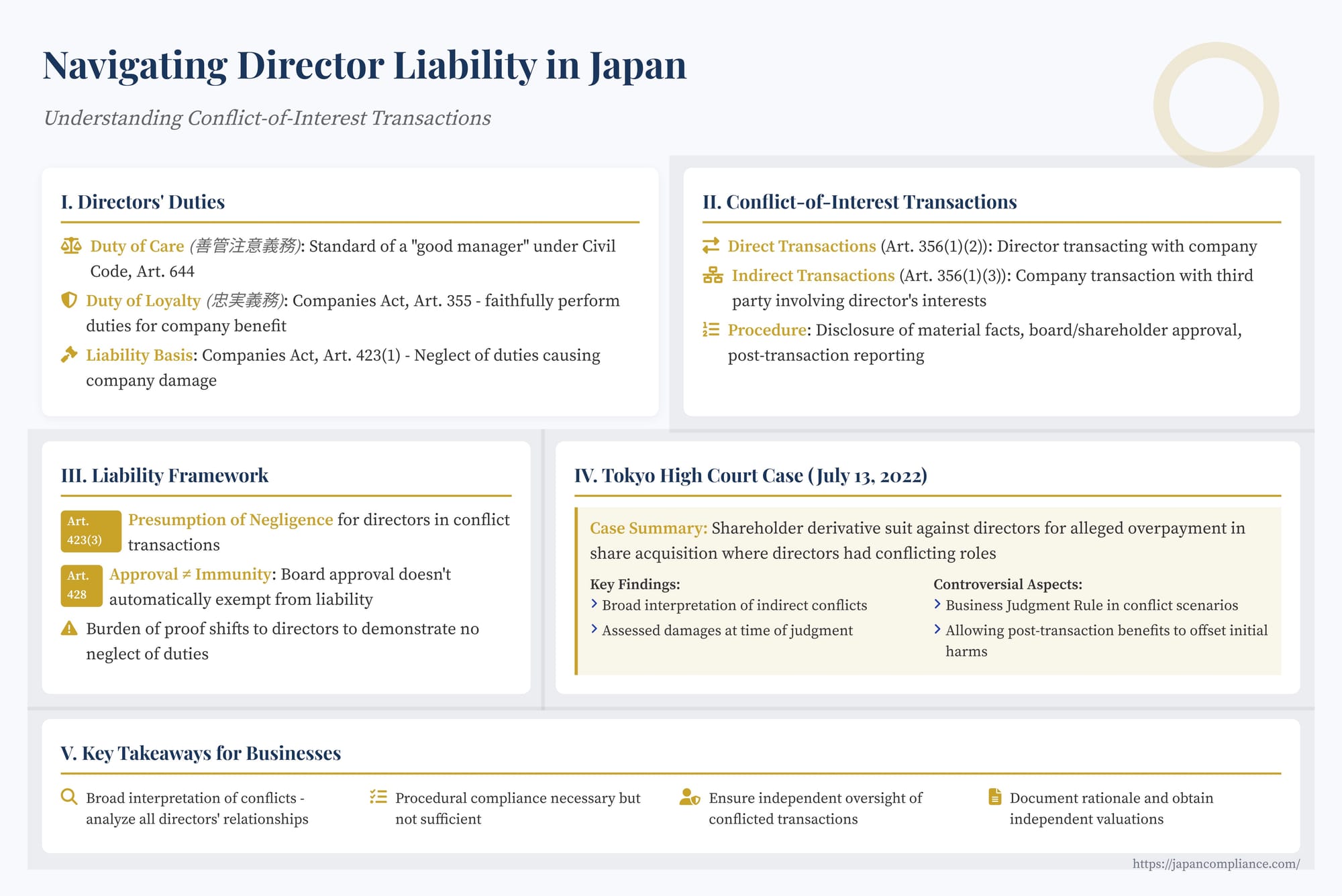

Under Japan's Companies Act, directors must both (1) act with the care of a “good manager” and (2) stay loyal to the company. Any deal that pits a director’s personal interest against the company’s (Article 356) demands full disclosure and board/shareholder approval—and even then directors can be personally liable if damage occurs. A 2022 Tokyo High Court case shows how hard it is to prove loss and why strong governance and truly independent approval are essential.

Table of Contents

- Duties of Care & Loyalty in Japan

- What Counts as a Conflict-of-Interest Transaction

- Procedure: Disclosure, Approval, Post-Report

- Liability: Articles 423 & 428 and the Negligence Presumption

- Tokyo High Court 13 July 2022 Case Study

- Five Compliance Take-Aways for Boards

Japanese corporate law imposes significant duties on company directors, demanding both diligence and loyalty. For international businesses operating in Japan or collaborating with Japanese companies, understanding the scope of these duties, particularly concerning conflict-of-interest transactions (利益相反取引 - rieki souhan torihiki), is crucial. A breach can lead to substantial personal liability for directors and complex legal challenges for the company. A recent Tokyo High Court decision highlights the nuances involved in identifying such conflicts and assessing director liability, offering valuable lessons in corporate governance.

Directors' Duties under the Japanese Companies Act

The foundation of director responsibility in Japan lies primarily in two duties mandated by the Companies Act (会社法 - Kaishahou) and supplemented by the Civil Code (民法 - Minpou):

- Duty of Care (善管注意義務 - Zenkan Chuui Gimu): Derived from the mandate relationship between a company and its directors (Companies Act, Art. 330; Civil Code, Art. 644), this requires directors to manage the company's affairs with the care of a "good manager." This standard is generally interpreted as the level of care a reasonably prudent person would exercise in a similar position and under similar circumstances. It encompasses a wide range of responsibilities, including overseeing business operations, making informed decisions, ensuring legal compliance, and establishing adequate internal controls.

- Duty of Loyalty (忠実義務 - Chuujitsu Gimu): Explicitly stated in Article 355 of the Companies Act, this duty requires directors to comply with laws, regulations, the articles of incorporation, and shareholder resolutions, and to perform their duties faithfully for the benefit of the company. While distinct in its wording, Japanese courts often view the Duty of Loyalty as clarifying or specifying the Duty of Care, rather than a separate, higher standard. It fundamentally prohibits directors from prioritizing their own interests or those of a third party over the company's interests, especially in situations involving potential conflicts.

Failure to meet these standards, resulting in damage to the company, can lead to director liability under Article 423 of the Companies Act. While directors are not liable for mere errors in judgment if they acted diligently and in good faith (often discussed in the context of the Business Judgment Rule - 経営判断の原則, keiei handan no gensoku), the application of this principle becomes significantly more complex when a director's personal interests are potentially involved.

Conflict-of-Interest Transactions: Definition and Procedure

Conflict-of-interest transactions represent a key area where the Duty of Loyalty is tested. The Companies Act specifically regulates these transactions to protect the company from potential harm arising from a director's divided loyalties.

What constitutes a Conflict-of-Interest Transaction?

Article 356, Paragraph 1 identifies two main categories:

- Direct Transactions (Item 2): When a director intends to transact directly with the company, either for their own account or for the account of a third party. Examples include a director selling personal property to the company, buying company assets, or receiving a loan from the company.

- Indirect Transactions (Item 3): When the company transacts with a third party, but the transaction indirectly involves a conflict with a director's interests. The classic example is the company guaranteeing a director's personal debt. Other situations might include transactions between the company and another entity substantially controlled by the director.

The underlying principle is whether there's a potential for the company's interests to be harmed due to the director's competing personal or third-party interests.

Procedural Requirements:

To proceed with a transaction falling under Article 356, Paragraph 1, specific procedures must be followed:

- Disclosure: The director involved must disclose all material facts concerning the proposed transaction to the relevant decision-making body.

- Approval: The transaction must be approved.

- For companies with a board of directors (取締役会設置会社 - torishimariyaku-kai setchi kaisha), approval requires a board resolution (Companies Act, Art. 365, Para. 1). The interested director cannot participate in this vote (Art. 369, Para. 2).

- For companies without a board of directors, approval requires a resolution at a shareholders' meeting (Companies Act, Art. 356, Para. 1).

- Post-Transaction Reporting (Board-Managed Companies): Following the transaction, the director involved must report the material facts concerning the transaction to the board without delay (Companies Act, Art. 365, Para. 2).

These procedures are designed to ensure transparency and allow the company (through its board or shareholders) to assess whether the transaction is fair and in the company's best interests, despite the potential conflict.

Consequences of Non-Compliance:

Failure to obtain the required approval generally renders a direct transaction voidable by the company. For indirect transactions involving third parties, the transaction's validity might be upheld if the third party acted in good faith and without knowledge of the lack of approval, reflecting a balance with transaction security. However, the lack of approval remains a breach of the director's duties.

Director Liability in Conflict Scenarios

Even if a conflict-of-interest transaction is procedurally approved, directors can still face liability if the company suffers damages as a result.

Basis for Liability (Article 423):

As mentioned, Article 423, Paragraph 1 establishes general liability for directors who neglect their duties and cause damage to the company.

Presumption of Negligence (Article 423, Paragraph 3):

Crucially, Article 423, Paragraph 3 establishes a presumption of negligence (任務懈怠の推定 - ninmu ketai no suitei) against directors involved in a conflict-of-interest transaction that causes damage to the company. This presumption applies to:

- The director who conducted a direct transaction with the company for themselves (Item 1).

- The director whose interests conflicted with the company's in an indirect transaction (Item 2).

- The director who proposed the transaction to the board (or other decision-making body) (Item 2).

- Directors who voted in favor of approving the transaction (Item 3).

This presumption shifts the burden of proof, requiring these directors to demonstrate they did not neglect their duties to avoid liability.

Approval is Not an Absolute Shield (Article 428):

Importantly, for a director who engaged in a direct transaction for their own benefit (自己のためにした取引 - jiko no tame ni shita torihiki), obtaining board or shareholder approval does not automatically exempt them from liability under Article 423, Paragraph 1 (Companies Act, Art. 428, Para. 1). They can still be held liable if negligence is proven, underscoring the heightened scrutiny applied to self-dealing transactions.

Case Study: Tokyo High Court, July 13, 2022 (Reiwa 4)

A decision by the Tokyo High Court provides significant insight into how these principles are applied, particularly regarding the scope of conflicts, damage assessment, and the role of the business judgment rule.

Background (Generalized):

A publicly listed company ("Company Z") was facing challenges due to long-term underperformance in its core business and potentially high overhead costs relative to its size, raising concerns about meeting listing standards. Seeking diversification and cost dispersion, Company Z's board decided to acquire a significant stake (just under 50%) in a private company operating in a different sector ("Company C").

The complexity arose because Company C's shares were sold by "Company B," which was the asset management company wholly owned by one of Company Z's directors ("Director Y1"). Director Y1 was also the representative director of Company B and Company C. Furthermore, another Company Z director ("Director Y2") served concurrently as an executive officer of Company Z and the representative director of Company C. A third director ("Director Y3") was the representative executive officer of Company Z.

The board resolution approving the acquisition plan (delegating detailed negotiation to the executive officers) excluded the conflicted Director Y1. The subsequent executive officer resolution finalizing the acquisition excluded Director Y2. Company Z proceeded with the acquisition, paying a substantial sum for the shares. Company Z later received significant management fees from Company C, which had previously paid such fees to a different entity.

Shareholders of Company Z initiated a derivative lawsuit against Directors Y1, Y2, and Y3, alleging that the purchase price for Company C's shares was excessively high and that the directors breached their duties of care and loyalty. Valuations presented varied significantly, with plaintiffs arguing for a much lower value than the purchase price, while even the valuation report Company Z referenced suggested a range considerably below the price paid.

Key Judgment Points:

The High Court ultimately dismissed the shareholders' claims, but its reasoning reveals important aspects of Japanese law:

- Identifying the Conflict (Judgment Point I): The court readily identified the transaction as a conflict of interest under Article 356.

- For Director Y1, who effectively controlled the seller (Company B) and the target (Company C), the conflict was direct and clear.

- More notably, the court also found Director Y2 to be in a conflict situation. Even though Y2 was a director of the target company (Company C) being acquired, not the seller, the court reasoned that a loss for Company Z (e.g., through overpayment) could indirectly benefit Y2 due to their position within Company C. This suggests a potentially broad interpretation of indirect conflicts, extending beyond direct transactional counter-parties or guarantors. The commentary accompanying the case report questioned whether simply being a director of the target company should automatically trigger conflict-of-interest status, hinting that the specific facts (perhaps Y2's broader group affiliations not detailed in the summary) might have influenced this finding. Y2, being deemed conflicted, should arguably not have participated in the initial board resolution delegating authority, although Y2 was excluded from the final executive resolution.

- Assessing Damages and the Presumption of Negligence (Judgment Point II): The court found that Company Z had not suffered damages at the time the court proceedings concluded. Its reasoning was that acquiring shares in another company as part of a business restructuring involves complex business judgment regarding future potential. The court stated that even if the purchase price exceeded the objective value at the time, damage doesn't automatically occur. It considered the subsequent benefits, such as the substantial management fees Company Z received from Company C post-acquisition, as evidence that the overall transaction did not ultimately result in a loss for Company Z when viewed at the time of judgment.

- Consequently, because no damage was recognized at that point, the court held that the presumption of negligence under Article 423, Paragraph 3 could not be applied against the directors.

- This approach to damage assessment is contentious. Critics argue that judging damages based on events long after the transaction, and potentially allowing subsequent gains to erase initial harm from an overpayment, undermines the purpose of scrutinizing the decision at the time it was made. The management fees, while beneficial, stemmed from the result of the acquisition, not necessarily justifying an initially inflated purchase price. This approach places a high burden on plaintiffs to prove quantifiable damage persisting through to the end of the litigation, potentially years later.

- Application of the Business Judgment Rule (Judgment Point III): Although finding no damage negated the need to assess negligence directly, the court addressed the directors' conduct. It acknowledged potential suspicions regarding the transaction's motives but also recognized the stated business rationale (addressing Company Z's strategic weaknesses, avoiding delisting risk).

- Crucially, the court applied the Business Judgment Rule. It stated that acquiring shares involves managerial expertise and judgment about future prospects. Unless the decision-making process or the substance of the decision was "grossly unreasonable" (著しく不合理 - ichijirushiku fugouri), directors should not be found to have breached their duty of care. The court concluded that, despite the pricing concerns raised by the plaintiffs, the acquisition was not grossly unreasonable in light of Company Z's circumstances and the potential benefits (including the later management fees).

- The application of the Business Judgment Rule to a clear conflict-of-interest transaction is highly debatable. Legal commentary emphasizes that in such situations, mere compliance with procedural requirements (like excluding conflicted directors from a vote) may not be sufficient. Ensuring genuine fairness requires demonstrating the independence of the remaining decision-makers and the substantive fairness of the transaction terms. The court's analysis appeared to lack a deep dive into the independence of the approving directors (like Y3) or robust scrutiny of the price justification at the time, instead relying heavily on the transaction not being "grossly unreasonable" in hindsight, potentially lowering the bar for directors involved in conflicted deals.

Key Takeaways:

The Tokyo High Court's decision, while dismissing the specific claims, offers several important takeaways for directors and companies operating under Japanese law:

- Broad Scope of Conflicts: Courts may interpret "indirect conflicts" broadly, potentially encompassing directors of target companies, not just counter-parties. A thorough analysis of all directors' relationships is essential.

- Procedural Compliance is Necessary but Not Sufficient: Following the approval procedures (disclosure, board/shareholder vote excluding conflicted directors) is vital, but does not guarantee immunity from liability, especially for the transacting director in a self-dealing scenario.

- Damage Assessment Can Be Complex: Proving damages resulting specifically from the conflict can be challenging, especially if the court considers long-term outcomes and applies a high threshold for recognizing loss. Plaintiffs face a significant burden.

- Business Judgment Rule in Conflict Zones: The extent to which the Business Judgment Rule shields directors involved in approving conflict-of-interest transactions remains contested. Relying on it requires demonstrating not just a lack of gross unreasonableness but also robust procedural fairness and independence in the decision-making process.

- Importance of Governance: The case underscores the need for strong corporate governance, particularly independent oversight. Thorough deliberation, potentially involving independent valuations and fairness opinions, and clear documentation of the rationale are critical when navigating transactions with potential conflicts.

Ultimately, directors in Japan must exercise heightened caution when personal interests potentially diverge from the company's. Proactive disclosure, adherence to strict procedural requirements, and ensuring decisions are demonstrably fair and made with independent oversight are paramount to mitigating liability risks associated with conflict-of-interest transactions.