Cyber-Incident Response in Japan: APPI Compliance & Cybersecurity Basics Explained

TL;DR

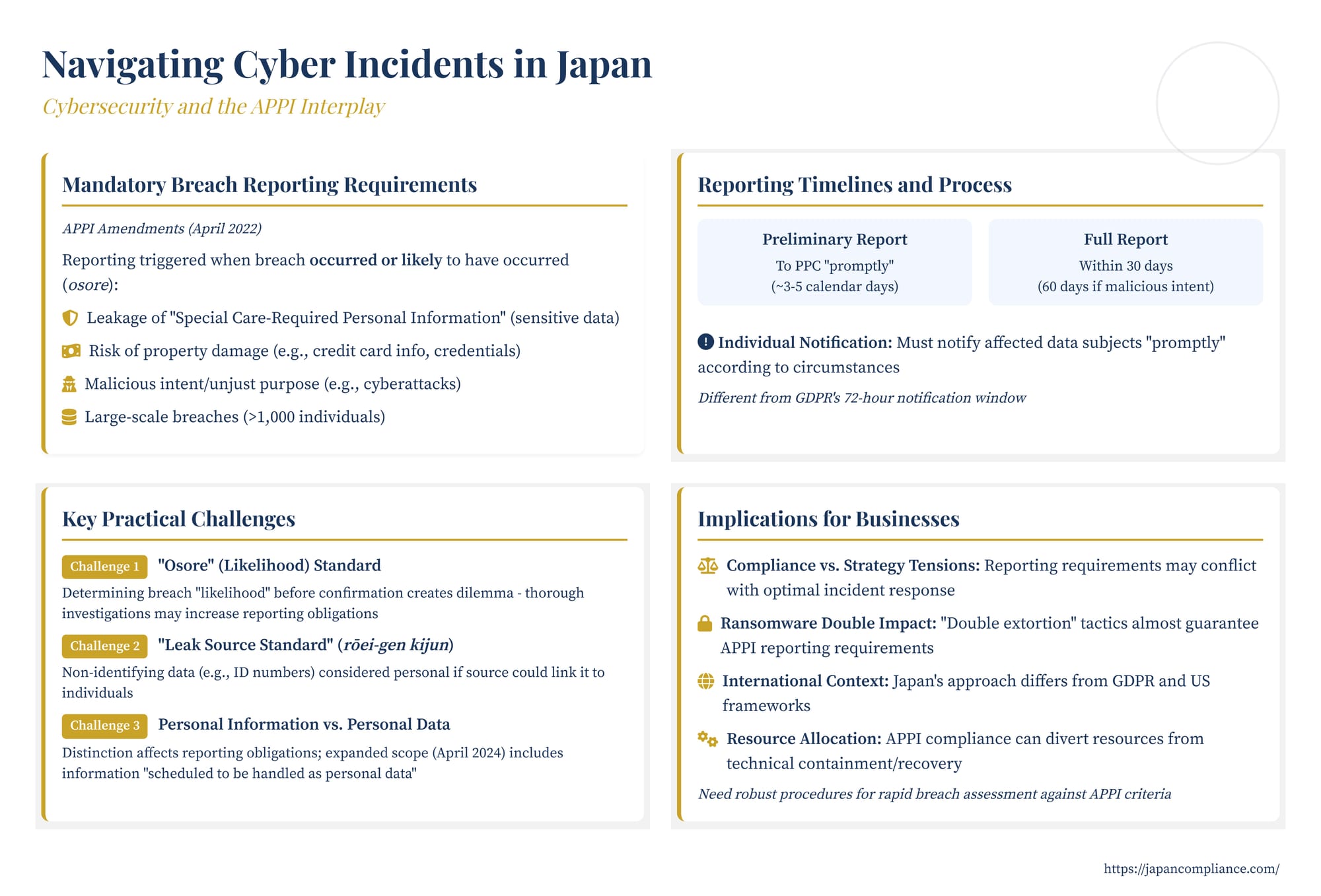

- Japan’s Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI) makes breach reporting mandatory when “personal data” is leaked—or likely leaked.

- Key pain points: the ambiguous “likelihood” (osore) standard, a strict two-stage reporting timetable, and the broad “leak source” test.

- Harmonising APPI compliance with best-practice incident response (esp. ransomware) requires advance playbooks and liaison with the PPC.

Table of Contents

- Mandatory Breach Reporting under the Amended APPI

- Reporting Timelines and Process

- Key Challenges in Practice: Navigating the Nuances

- Incident Response Dilemmas: Compliance vs. Strategy

- The Impact of Ransomware

- The Role of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC)

- International Context and Conclusion

Cybersecurity incidents are an unfortunate but increasingly common reality for businesses operating globally. As threats evolve in sophistication and frequency, legal frameworks governing data protection and incident response also adapt. In Japan, the primary legislation shaping how organizations must react to data breaches is the Act on the Protection of Personal Information (APPI). Recent amendments have significantly altered the landscape, making a clear understanding of its requirements crucial for any company handling the personal information of individuals in Japan.

For years, cybersecurity incident response in Japan has been heavily influenced by, and often equated with, responding to personal information leaks under the APPI. While this focus has undoubtedly spurred security enhancements, particularly concerning customer data, the legal obligations surrounding incidents, especially data breaches, underwent a significant overhaul effective April 1, 2022. Before this date, reporting data breaches to the regulatory authority and notifying affected individuals was largely based on a "duty to make an effort." The 2022 amendments transformed this into a mandatory obligation under specific circumstances, aligning Japan more closely with global trends but also introducing unique complexities.

Mandatory Breach Reporting under the Amended APPI

The cornerstone of Japan's current incident response framework is the mandatory duty for business operators handling personal information (referred to as "personal information controllers") to report certain types of data security incidents to the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC) and notify the affected data subjects. This duty is triggered not only when a breach has definitively occurred but also when it is likely to have occurred (osore).

The types of incidents mandating a report to the PPC and notification to individuals include situations involving:

- Leakage of "Special Care-Required Personal Information": This category includes sensitive data like race, creed, social status, medical history, criminal record, etc.

- Risk of Property Damage: Incidents where leaked personal information could be used for illicit purposes resulting in property damage (e.g., unauthorized use of credit card information or login credentials).

- Malicious Intent: Breaches potentially carried out for an "unjust purpose," such as those caused by unauthorized access (cyberattacks) or embezzlement.

- Large-Scale Breaches: Incidents involving the personal data of more than 1,000 individuals.

This mandatory reporting represents a significant shift from the pre-April 2022 regime. Understanding these triggers is the first step in navigating compliance during a cyber incident.

Reporting Timelines and Process

The amended APPI establishes a two-stage reporting process to the PPC:

- Preliminary Report: Business operators must submit a preliminary report "promptly" after becoming aware of a qualifying incident (or the likelihood thereof). Guidelines suggest this means within approximately 3 to 5 calendar days. This initial report covers the information known at that point.

- Full Report: A detailed, comprehensive report must follow within 30 calendar days of becoming aware of the incident. However, if the breach involves malicious intent (like unauthorized access), this deadline is extended to 60 calendar days.

Crucially, alongside reporting to the PPC, the business operator must also notify the affected data subjects "promptly" according to the circumstances. Unlike the GDPR, which mandates a 72-hour notification window to the supervisory authority (though not necessarily to data subjects immediately), the APPI emphasizes promptness based on situational factors for individual notification, while setting slightly longer, but firm, deadlines for regulatory reporting.

Key Challenges in Practice: Navigating the Nuances

While the framework appears structured, practical application reveals several challenges for businesses, particularly multinational corporations accustomed to different regulatory environments.

1. The Ambiguity of "Osore" (Risk/Likelihood)

One of the most significant practical hurdles is the requirement to report incidents where a breach is merely likely (osore がある場合). The APPI guidelines explain this applies when leakage is suspected based on known facts, even if not definitively confirmed. Determining this "likelihood" threshold, especially in the immediate aftermath of a sophisticated attack like ransomware where the extent of data exfiltration is often unclear, can be extremely difficult.

This creates a dilemma: a superficial investigation might conclude that a reportable breach is not "likely," potentially reducing compliance burdens in the short term. However, a more thorough, diligent forensic investigation might uncover evidence suggesting a breach was likely, thereby triggering reporting obligations. This situation can inadvertently penalize companies that invest heavily in deep investigations, as they are more likely to uncover facts pushing them over the reporting threshold, even for potential, rather than confirmed, breaches. The ambiguity forces companies to make difficult judgment calls under pressure, often opting for broader reporting to mitigate regulatory risk, which in turn triggers the demanding process of individual notification.

2. The "Leak Source Standard" (漏えい元基準)

Another complexity arises from the interpretation of what constitutes "personal data" in the context of a breach. Official Q&A accompanying the APPI guidelines introduced a concept sometimes referred to as the "leak source standard" (漏えい元基準). Under this interpretation, information that does not, on its own, identify a specific individual (e.g., an internal employee ID consisting of a random string) can still be treated as personal data if the entity from which it leaked (the "leak source") holds other information that could be used, in combination with the leaked data, to identify a specific individual.

For example, if only employee IDs are exfiltrated in a breach, these IDs might seem anonymous to the outside world. However, because the employer maintains an employee database linking these IDs to names and other identifying information, the leakage of the IDs alone can constitute a breach of personal data under the APPI, triggering reporting and notification duties. This standard requires businesses to assess not just the leaked data itself, but also its potential linkability within their own systems, adding another layer of complexity to breach assessment and potentially broadening the scope of reportable incidents beyond what might be expected under other privacy regimes. Some argue this interpretation places an excessive burden on businesses and question whether notifying individuals about the potential leak of seemingly anonymous data like an internal ID provides meaningful value or simply causes unnecessary confusion and anxiety.

3. Personal Information vs. Personal Data

The APPI distinguishes between "personal information" (broadly, information relating to a living individual that can identify them) and "personal data" (personal information that is part of a systematically organized database, etc.). The mandatory reporting obligations primarily attach to breaches of "personal data." However, this distinction can be challenging in practice.

Consider files like individual PDF quotes stored on a server. A single quote containing a customer's name might be "personal information" but not necessarily "personal data" if not part of a structured database. But what if numerous quotes are stored within a folder named "Quotes"? Does the organization transform them into "personal data"? This classification matters, especially when assessing if the "1,000 individuals" threshold for mandatory reporting is met.

Furthermore, a rule change effective April 1, 2024, complicated matters regarding breaches involving "improper purpose" (trigger #3 above). The scope was expanded to include not just personal data, but also personal information that the business has acquired or is trying to acquire and which is scheduled to be handled as personal data. This seemingly targets scenarios like web skimming where payment information might be stolen during input before being formally stored in a database. However, it could potentially apply to situations like the theft of physical business cards intended for entry into a contact management system, raising concerns about the practicality and reasonableness of the expanded scope.

Incident Response Dilemmas: Compliance vs. Strategy

The strict reporting timelines and notification duties under the APPI can sometimes conflict with optimal cybersecurity incident response strategies. In highly sophisticated attacks, such as state-sponsored espionage or complex ransomware intrusions, immediate public disclosure or notification might hinder ongoing investigations or remediation efforts. Attackers might be alerted, change tactics, or destroy evidence if a breach is announced prematurely.

Security professionals often emphasize the need for a carefully managed response, potentially delaying public communication until the intrusion is contained, the scope fully understood, and recovery is underway. However, the APPI's mandatory framework, particularly the prompt notification requirement for individuals and the relatively short preliminary reporting window to the PPC, can limit this flexibility.

Companies facing major incidents report that significant resources – human, financial, and technical – are consumed by APPI compliance activities (investigating potential data compromise, identifying affected individuals, preparing notifications, liaising with the PPC). This necessary focus on data protection compliance can, in some cases, divert critical resources from the technical tasks of threat containment, eradication, and system recovery. This tension highlights a potential misalignment between data privacy regulation focused on individual rights and harm mitigation, and cybersecurity best practices focused on neutralizing threats and ensuring operational resilience. Some experts argue that the system treats cybersecurity incidents primarily as personal information leaks, potentially overlooking broader security implications or hindering the most effective defense against persistent attackers.

The Impact of Ransomware

The global surge in ransomware attacks presents a particularly acute challenge in the context of the APPI. Modern ransomware tactics frequently involve "double extortion": attackers not only encrypt the victim's data (causing operational disruption and data damage) but also exfiltrate sensitive data before encryption, threatening to leak it publicly if the ransom is not paid (causing a data leak).

This combination almost guarantees that a significant ransomware incident will trigger mandatory APPI reporting obligations. The data exfiltration aspect often involves personal data, potentially hitting one or more of the mandatory reporting triggers (e.g., malicious intent, potential property harm if financial data is stolen, or simply exceeding the 1,000-record threshold due to the volume of data typically stolen).

Furthermore, the nature of ransomware has shifted. While earlier attacks often targeted organizations holding obviously valuable data (like financial institutions or healthcare providers), current strains frequently target organizations indiscriminately, encrypting whatever data they can access simply to disrupt operations and coerce a ransom payment. The value of the data to the attacker is secondary to the value of operational continuity to the victim. This means a wider range of businesses, including those who previously felt they weren't prime targets for data theft, are now vulnerable to attacks that inevitably have APPI implications due to the high likelihood of data exfiltration accompanying encryption.

The Role of the Personal Information Protection Commission (PPC)

The PPC is Japan's independent data protection authority. It receives breach reports, issues guidance on APPI interpretation, conducts investigations, and has the power to issue recommendations and administrative orders, as well as impose administrative fines (though criminal penalties also exist).

The PPC plays a central role in the breach response ecosystem. However, discussions among experts suggest potential areas for evolution. With the mandatory reporting rules, the PPC now accumulates a vast amount of data on cybersecurity incidents affecting Japan. There is a call for this data to be more actively analyzed and leveraged to provide actionable threat intelligence back to the business community. While the PPC does engage in information sharing with law enforcement (like the National Police Agency's Cyber Police Bureau), there's a perception that more could be done to translate the reported breach data into proactive, preventative guidance and trend analysis that could help other organizations bolster their defenses against common attack vectors (like the specific VPN vulnerabilities heavily exploited in past ransomware campaigns). Effectively anonymizing and sharing aggregated attack patterns and TTPs (Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures) derived from breach reports could significantly enhance the nation's overall cybersecurity posture.

International Context and Conclusion

For multinational companies, navigating Japan's APPI requirements adds another layer to the already complex global tapestry of data breach laws. Key differences exist compared to frameworks like the EU's GDPR or the patchwork of US state laws. The triggers for reporting (especially the "osore" likelihood standard and the specific categories like "unjust purpose"), the multi-stage reporting timeline, the interpretation of "personal data," and the strong emphasis on prompt individual notification are all areas where Japan's approach has distinct characteristics.

Successfully managing a cyber incident involving Japanese personal data requires more than just technical expertise; it demands a nuanced understanding of the APPI's specific obligations. Businesses need robust internal procedures not only for detecting and responding to threats but also for rapidly assessing potential data breaches against the APPI's mandatory reporting criteria. This includes evaluating the likelihood of a breach, understanding the scope and nature of potentially affected data (including its linkability under the "leak source standard"), and being prepared to engage with the PPC and notify affected individuals promptly when required. Balancing these legal duties with strategic security responses and managing resources effectively remains a critical challenge for legal and business professionals operating in or connected to the Japanese market.

- Decoding Data Privacy and Cybersecurity in Japan: A Guide for US Businesses

- AI in Digital Forensics and Cybersecurity: Navigating the Japanese Legal Landscape

- Privacy in Japan: Navigating Tort Law and Data Protection for US Companies

- Personal Information Protection Commission – English Portal

- Guidance for Organisations During Ransomware Incidents (NISC, PDF)