Navigating Cross-Border Inheritance: A Landmark Japanese Supreme Court Ruling on Real Estate and Conflict of Laws

Date of Judgment: March 8, 1994

Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

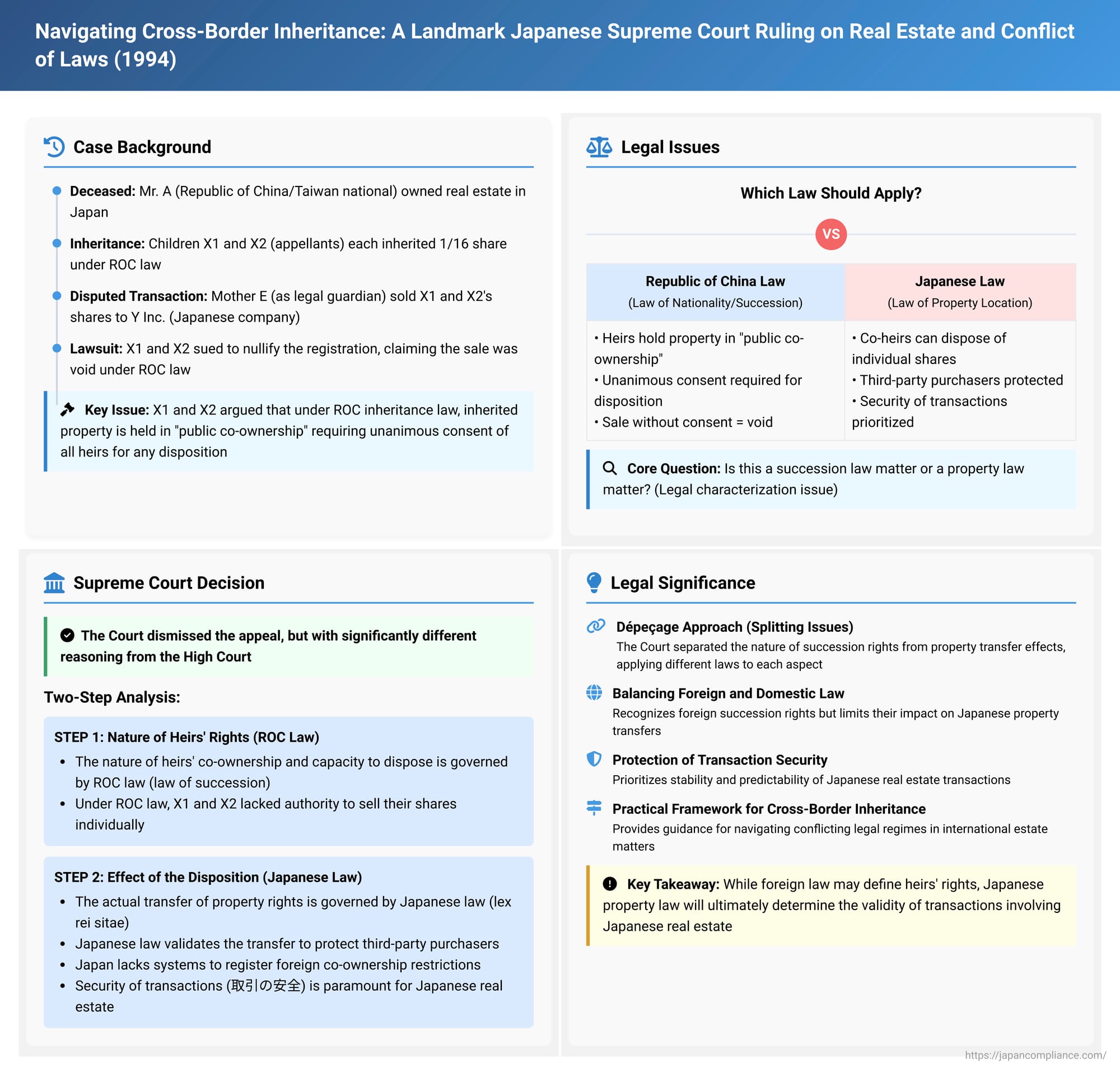

The complexities of international inheritance, particularly when real estate is involved, often present challenging legal questions. Different countries have different rules governing who inherits, what rights they have, and how property can be transferred. When these differing legal systems intersect, courts must decide which country's laws apply to which aspects of the dispute. This process, known as "conflict of laws" or "private international law," was at the heart of a significant Japanese Supreme Court decision issued on March 8, 1994. The case involved heirs of a foreign national who owned property in Japan, and it provides crucial insights into how Japanese courts resolve such conflicts, especially the interplay between succession law and property law.

The Factual Matrix: An Inheritance Spanning Jurisdictions

The case revolved around Mr. A, a national of the Republic of China (Taiwan), who passed away owning real estate in Japan. Upon his death, an inheritance process commenced. According to the conflict of laws rules applicable at the time (Article 25 of Japan's then-Horei, the Act on Application of Laws, which has principles similar to Article 36 of the current Act on General Rules for Application of Laws), the succession itself was to be governed by the laws of Mr. A's nationality – the Republic of China.

Mr. A had two children, X1 and X2 (the appellants in the Supreme Court). Under Republic of China law, X1 and X2 each acquired a 1/16th share in their father's estate as co-heirs. However, before any formal division of the estate assets among the heirs took place, their mother, E, acting as their legal guardian, sold X1's and X2's respective 1/16th shares in the Japanese real estate to Y Inc., a Japanese real estate development company (the respondent). The transfer of these shares was duly registered in the Japanese property registry.

Subsequently, X1 and X2 initiated legal proceedings against Y Inc. Their goal was to have the registration of the share transfer nullified, arguing that the underlying sale agreement was void. Their central argument hinged on the provisions of Republic of China law, the designated law of succession. They contended that under ROC law, inherited property, prior to its formal division, is held in a special form of co-ownership by the heirs, termed "public co-ownership" (公同共有 - kōdō kyōyū). A critical feature of this type of co-ownership, they argued, was that any disposition of a share in the publicly co-owned property required the unanimous consent of all co-heirs. Since such unanimous consent had not been obtained for the sale of their shares to Y Inc., X1 and X2 asserted that the sale was invalid, and consequently, Y Inc. had not legally acquired their interests in the Japanese real estate.

The Legal Labyrinth: Which Law Applies?

The core of the dispute lay in determining the applicable law. Should the rules of the Republic of China, governing the succession, dictate the validity of the share sale? Or should Japanese law, as the law of the location of the real estate (lex rei sitae), take precedence? This question involves a fundamental step in private international law known as "characterization" (性質決定 - seishitsu kettei) – essentially, categorizing the legal issue to determine which conflict of laws rule, and therefore which jurisdiction's substantive law, should apply.

The lower court, the Tokyo High Court, had taken a relatively straightforward approach. It characterized the entire dispute, including the question of whether the heirs had the power to dispose of their shares, as a matter of property law. Consequently, it applied Japanese law (Article 10 of the old Horei, which directs property matters to the lex rei sitae). Under the Japanese Civil Code, co-heirs are generally considered to hold their shares in a form of co-ownership (共有 - kyōyū) that allows them to dispose of their individual shares without needing the consent of other co-heirs. Based on this, the High Court dismissed the claims of X1 and X2, upholding the validity of the sale to Y Inc.

X1 and X2 appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

The Supreme Court's Nuanced Approach: A Two-Step Analysis

The Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 8, 1994, ultimately dismissed the appeal by X1 and X2, meaning Y Inc. was confirmed as the valid owner of the shares. However, the Supreme Court arrived at this conclusion through a significantly different and more nuanced reasoning process than the High Court. It found that the High Court had erred in its characterization of the issues.

The Supreme Court effectively adopted a two-step analysis, "splitting" the legal issues and assigning different governing laws to different aspects of the case (a technique sometimes referred to as dépeçage in private international law).

Step 1: The Nature of Heirs' Rights and Capacity to Dispose – Governed by the Law of Succession (ROC Law)

The Supreme Court first addressed the question of the legal nature of X1 and X2's co-ownership of the inherited Japanese real estate and their capacity or power to dispose of their shares before the estate was formally divided. The Court ruled that these matters are intrinsically linked to the "effects of inheritance." As such, they should be governed by the law designated by the conflict rule for succession – in this case, Article 25 of the old Horei, which pointed to the law of the deceased's nationality: the Civil Code of the Republic of China.

The Court then examined the relevant provisions of the ROC Civil Code:

- Article 1151 stipulated that if there are multiple heirs, the entire estate, prior to its division, is "publicly co-owned" (kōdō kyōyū) by all the heirs. The Supreme Court interpreted this "public co-ownership" as being equivalent to a form of joint ownership known as gōyū (合有), which is analogous to the German concept of Gesamthandseigentum. In this type of ownership, individual co-owners do not have distinct, alienable shares but rather a collective interest in the whole.

- Article 828, paragraph 1, of the ROC Civil Code stated that the rights and obligations of public co-owners are determined by the specific law or contract establishing that co-ownership.

- Crucially, Article 828, paragraph 2, provided that, unless otherwise stipulated, any disposition of the publicly co-owned property, or the exercise of other rights over it, requires the consent of all public co-owners.

Applying these ROC law provisions, the Supreme Court found that, according to the governing law of succession:

- The Japanese real estate was indeed held in a state of joint ownership (gōyū) by Mr. A's heirs.

- Consequently, X1 and X2, as individual co-heirs, were not permitted to dispose of their undivided interests in the property before the formal division of the estate unless they had obtained the consent of all other co-heirs.

- The Court acknowledged, based on the facts established by the lower court, that the sale of the shares to Y Inc. had occurred before the estate was divided and without the unanimous consent of all co-heirs.

Therefore, under the lex successionis (ROC law), X1 and X2 had acted beyond their legal capacity when they sold their shares. This part of the Supreme Court's analysis directly contradicted the High Court's finding that the heirs' power of disposition was a matter for Japanese law.

Step 2: The Effect of the Disposition on Property Rights – Governed by the Law of the Property's Location (Japanese Law)

Having established that X1 and X2 had acted contrary to the provisions of the applicable succession law (ROC law), the Supreme Court then turned to the critical next question: what is the effect of this non-compliant disposition on the transfer of property rights in Japanese real estate?

On this point, the Supreme Court stated that the question of whether a disposition of property actually results in a transfer of legal rights (a "change in real rights" - 物権変動, bukken hendō) is to be determined by the law of the place where the property is located (lex rei sitae). In this case, since the real estate was in Japan, Japanese law governed the effectiveness of the transfer. This was based on Article 10, paragraph 2, of the old Horei, which stipulated that the acquisition or loss of rights in rem (property rights) is governed by the law of the location of the property at the time the facts constituting the cause of such acquisition or loss are completed.

The Supreme Court then declared that, under Japanese law, such a disposition – even one made by heirs who, under their personal succession law, lacked the authority to make it individually – is considered valid in relation to the third-party purchaser. Thus, Y Inc. had effectively acquired the shares.

The Court provided several justifications for this interpretation of Japanese law and its prevailing effect in this context:

- Lack of Public Notice for Foreign Restrictions: The Court noted that even if a foreign succession law imposes a joint ownership (gōyū) status on inherited property and restricts individual heirs from disposing of their shares, Japanese law lacks a system for publicizing such specific foreign-derived joint ownership statuses or the associated restrictions on disposition for real estate located in Japan. The Japanese property registration system is designed around Japanese concepts of property rights.

- Japanese Domestic Law on Co-Inheritance: Under Japanese law, when co-heirs jointly inherit property before its division, their legal relationship is fundamentally treated as a form of "co-ownership in shares" (共有 - kyōyū), governed by Article 249 et seq. of the Japanese Civil Code. The Court cited its own precedent (Supreme Court judgment, May 31, 1955) supporting this understanding.

- Protection of Third-Party Acquirers: The Court also referenced another of its precedents (Supreme Court judgment, February 22, 1963), which established that a third party who acquires a co-ownership share in specific inherited real estate from one co-heir can legally and effectively obtain that right under Japanese law.

- Security of Transactions (取引の安全 - torihiki no anzen): This was a paramount consideration. The Supreme Court emphasized that if dispositions of Japanese real estate were to be invalidated merely because they did not comply with such restrictions found in a foreign law of succession (restrictions that are not readily apparent or registrable in Japan), it would severely undermine the security and predictability of real estate transactions in Japan. Parties dealing with Japanese real estate rely on the Japanese legal framework and its registration system.

Therefore, the Supreme Court concluded that even though X1 and X2 had sold their shares without the consent of all co-heirs, as required by ROC law (the lex successionis), the transfer of rights to Y Inc. was nonetheless effective under Japanese law (the lex rei sitae).

The Outcome: High Court's Conclusion Upheld, but on Different Grounds

In summary, the Supreme Court found that the High Court had made an error in its choice of applicable law regarding the nature of the heirs' rights and their capacity to dispose of inherited shares; these aspects, the Supreme Court clarified, were indeed matters for the law of succession (ROC law). However, the ultimate effect of the disposition on the property title in Japan was a matter for Japanese law. Since Japanese law validated the transfer to protect transactional security, the High Court's final conclusion – dismissing the heirs' claim and upholding the sale – was correct, albeit reached through flawed reasoning. The appeal by X1 and X2 was therefore dismissed.

Deeper Implications of the Supreme Court's Logic

This landmark decision carries significant implications for understanding Japanese private international law.

1. Affirming the Scope of the Law of Succession:

The judgment clearly demarcates that the legal status of co-heirs, the nature of their collective ownership (e.g., gōyū or kyōyū), and their inherent powers or limitations regarding the disposition of inherited assets are, in principle, determined by the lex successionis. This affirmed that the core aspects of the inheritance relationship itself fall under the deceased's personal law.

2. The Overriding Power of Lex Rei Sitae for Property Transfer Effects:

Simultaneously, the decision robustly upholds the principle that the lex rei sitae governs the actual transfer of title and the creation of real rights in property. This is particularly potent for immovable property, where the connection to the jurisdiction of its location is strongest.

3. The "Realizability" of Foreign Law and Public Policy:

The Court's reasoning highlights a crucial tension: while the lex successionis might impose certain forms of ownership or restrictions, their practical enforcement concerning property in another country depends on whether the legal system of the lex rei sitae can recognize or give effect to them.

The Supreme Court's logic can be seen as:

* The effect of any property transfer (the bukken hendō) is governed by Japanese law as the lex rei sitae.

* Japanese substantive law, when applied to the facts, validates the transfer to the third party (Y Inc.), even if the co-heirs (X1 and X2) lacked the proper authority to dispose of their shares under the lex successionis (ROC law).

The justifications for this stance by the Supreme Court were essentially:

* Practicality/Publicity: There is no mechanism in Japan to formally register or give public notice to third parties about the specific type of "joint ownership" (gōyū) and the associated disposition restrictions mandated by the ROC law of succession. Third parties transacting in Japanese real estate would typically rely on what is (or can be) recorded in the Japanese property register.

* Domestic Analogy and Transaction Security: Japanese domestic inheritance law generally treats the co-ownership of an undivided estate by co-heirs as kyōyū (co-ownership in shares), where individual co-heirs can typically dispose of their respective shares. To invalidate a transaction with a third party based on unfamiliar foreign restrictions would, as the Court stressed, severely compromise the security of transactions (torihiki no anzen). This principle is a cornerstone of Japanese commercial and property law.

Essentially, the Supreme Court's position implies that while the co-heirs' rights and the nature of their ownership (e.g., being in a gōyū relationship) are defined by the lex successionis, the realization or effectuation of these particular foreign legal constructs in a property transaction within Japan can be constrained by the capabilities and overriding policies of the lex rei sitae (Japanese law). If the lex rei sitae does not have a comparable legal mechanism or if giving full effect to the foreign rule would violate fundamental principles like transactional security, the foreign rule may not be fully applied to the detriment of a bona fide third-party purchaser in Japan.

The Court clarified that the co-heirs' ownership structure and their disposition rights are, in the first instance, matters for the lex successionis. However, if the specific rules imposed by the lex successionis (like the gōyū status and its inalienability by individual heirs) cannot be effectively implemented or recognized within the property law system of the lex rei sitae (Japan), particularly where it concerns the rights of third-party acquirers, then the lex rei sitae will determine the outcome of the purported property transfer.

This does not mean the lex successionis is entirely ignored. It determined that X1 and X2 should not have sold their shares individually. However, their failure to comply with ROC law did not automatically void the transaction under Japanese property law when a third party's rights were at stake.

Concluding Observations

The Supreme Court's March 8, 1994 decision is a pivotal judgment in Japanese private international law. It meticulously navigates the difficult terrain where inheritance law and property law, derived from different legal systems, intersect. The ruling underscores a pragmatic approach: it respects the domain of the deceased's personal law in defining the core inheritance relationships and rights, but it also safeguards the integrity and security of property transactions occurring within Japan under Japanese law.

The case illustrates that while foreign law may govern certain aspects of an heir's status and rights, the ultimate effect of their actions concerning Japanese real estate, especially in relation to third parties, will be decisively shaped by Japanese property law and its underlying policy considerations, most notably the imperative of ensuring the security of transactions. This delicate balancing act remains a critical feature of resolving complex cross-border legal issues.