Navigating Corporate Leadership in Crisis: Provisional Court Orders and Director Powers in Japan

Case: Action for Confirmation of Land Ownership, etc.

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench, Judgment of November 6, 1970

Case Number: (O) No. 834 of 1965

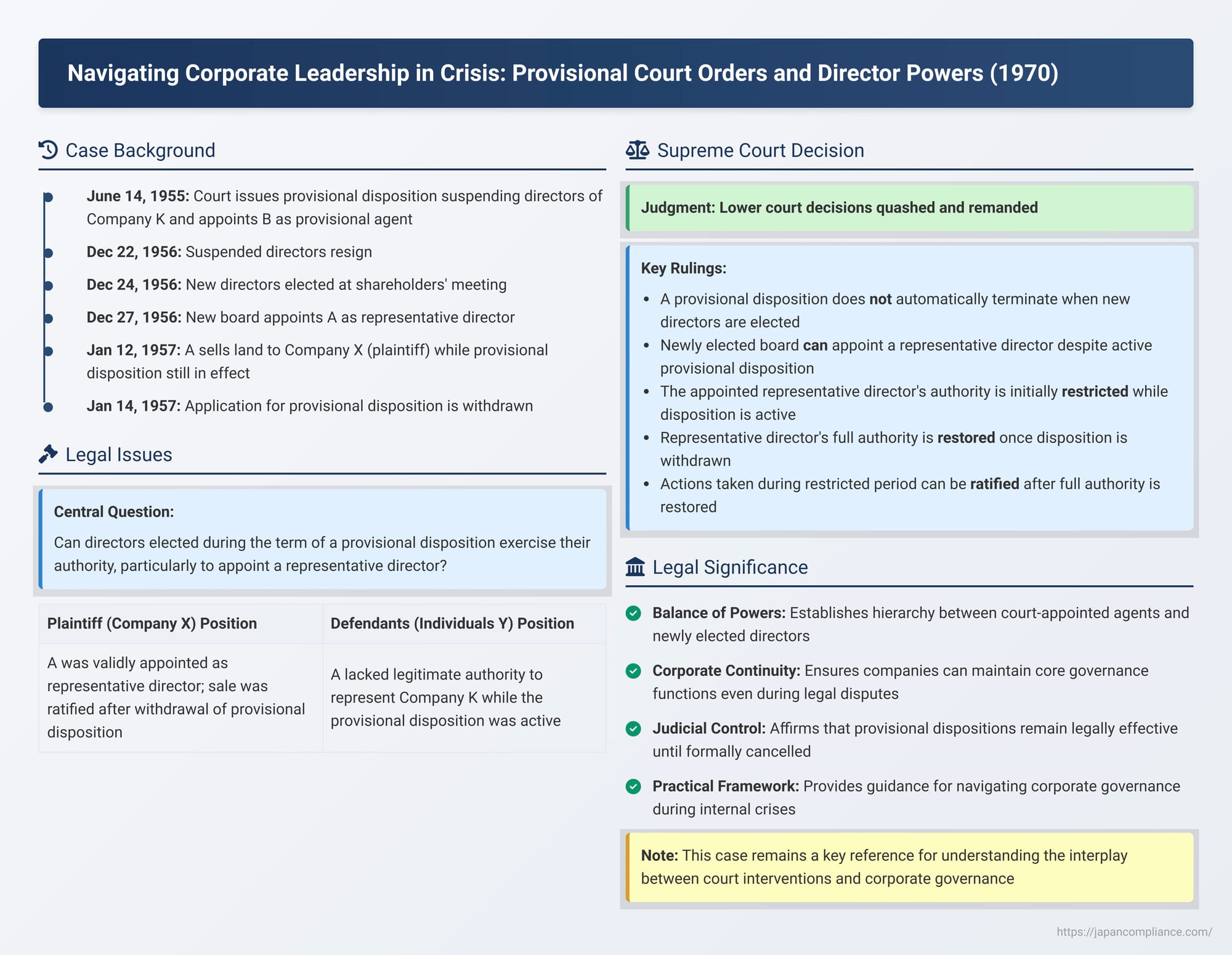

When internal turmoil grips a company, leading to legal challenges against its directors, courts can issue provisional dispositions (interim orders) to suspend the duties of those directors and appoint provisional agents (shokumu daikōsha) to manage the company's affairs. This is a crucial mechanism to maintain stability pending a final resolution of the underlying dispute. But what happens to the authority of these court-appointed agents and the company's governance if the suspended directors resign and new directors are elected by shareholders, all while the provisional disposition remains technically in effect? A landmark Supreme Court decision on November 6, 1970, provided critical clarification on the lingering effects of such orders and the powers of newly appointed leadership.

A Tangled Web of Land Deals and Boardroom Turmoil: Facts of the Case

The case centered on a dispute over the ownership of several plots of land originally belonging to Company K (an auxiliary participant in the lawsuit).

- Individuals Y (the defendants/respondents) claimed they had acquired the land from Company K through sale or other means on February 9 or 10, 1956, and had completed the necessary ownership transfer registrations.

- Company X (the plaintiff/appellant) asserted that it had purchased the same land from Company K, represented by its representative director A, on January 12, 1957. Company X argued that the earlier transaction with Individuals Y was invalid because it was conducted by individuals who were not legitimate representatives of Company K at the time. X therefore sought confirmation of its own ownership and the necessary registration procedures.

The crux of the matter lay in the authority of A to act as Company K's representative director during the sale to Company X, given the complex internal situation at Company K:

- Provisional Disposition: On June 14, 1955, a provisional court order had suspended the duties of all of Company K's then-incumbent directors (which included A among others, before he later became representative director). In their place, B and three other individuals were appointed as provisional agents (shokumu daikōsha) to carry out the directors' duties. Further, on February 20, 1956, B was specifically appointed as the provisional agent for the representative director of Company K (under provisions of the then-Commercial Code, Articles 261(3) and 258(2)).

- Resignation and New Appointments During Active Disposition: While this provisional disposition was still in full force:

- On December 22, 1956, all the directors whose duties had been suspended (including A in his prior capacity) resigned from their positions.

- On December 24, 1956, a shareholders' meeting of Company K was held, and four new directors were elected.

- This newly elected board of directors then held a meeting on December 27, 1956, and appointed A (one of the newly elected directors) and another individual as representative directors of Company K. These appointments were registered on January 12, 1957.

Individuals Y, defending their claim to the land, argued that since the provisional disposition appointing the agents was still active and had not been formally cancelled by a court, A lacked the legitimate authority to represent Company K in the sale to Company X. Therefore, they contended, X's purported purchase was invalid.

Company X countered that even if A initially lacked authority, the application for the provisional disposition had been withdrawn on January 14, 1957. X asserted that A subsequently ratified the sale on its behalf on January 17, 1957, or, alternatively, again on April 25, 1957, thus validating the transaction.

The lower courts (Fukuoka District Court and Fukuoka High Court) sided with Individuals Y. They found that A had not been validly appointed as representative director and consequently lacked the authority to sell the land to Company X, rendering X's claim invalid. Company X appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Clarification: A Two-Step Analysis

The Supreme Court quashed the lower courts' decisions and remanded the case back to the Fukuoka High Court for further proceedings, based on a different interpretation of the law concerning provisional dispositions.

Reasoning of the Apex Court: Validity, Restriction, and Release

The Supreme Court meticulously outlined its reasoning:

- Nature of the Provisional Disposition: A provisional disposition that suspends a director's duties and appoints a provisional agent (issued under the then-Commercial Code Article 270, a measure similar in nature to what is now governed by Article 23, Paragraph 2 of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act) is designed to establish a temporary legal status pending the outcome of a main lawsuit (e.g., a suit challenging the director's appointment). Such a disposition naturally loses its effect when the judgment in the main case becomes final and binding.

- Effect of Resignation/New Appointment on the Disposition's Validity: The Court held that if directors whose duties have been suspended by a provisional order subsequently resign, and a shareholders' meeting then elects new directors, these events do not, by themselves, automatically cause the provisional disposition to lose its validity or terminate the authority of the court-appointed provisional agents. The disposition remains legally effective until it is formally cancelled by a court. Such cancellation would typically occur if a court, upon application, determines that there has been a significant "change in circumstances" (such as the valid appointment of new, untainted directors) warranting the termination of the provisional measures. The mere fact of new appointments is a ground to request cancellation, not an automatic trigger for it. The Supreme Court reasoned that the law requires such changes to be ascertained through judicial process before a provisional order is nullified.

- Distribution of Powers While the Disposition is Active:

- General Principle: When a provisional agent has been appointed to perform directorial duties, those duties are, in principle, to be carried out by the agent. Consequently, any newly appointed regular directors find their own authority to execute directorial duties restricted to that extent; they cannot freely override or duplicate the agent's functions.

- Key Exception – Appointing a Representative Director: However, the Court carved out an important exception. If, after the suspended directors resign and new directors are validly elected by shareholders, the company finds itself lacking a representative director, these newly appointed directors can legitimately form a board of directors and appoint a representative director from among themselves. The Supreme Court reasoned that such an act:

- Does not inherently conflict with the purpose or content of the original provisional disposition (which was primarily aimed at the suspended directors and their specific issues).

- Is practically necessary for the company's ability to function and be represented, aligning with the purpose of having a representative director system. Appointing a representative director is a fundamental governance act, not typically performed by a provisional agent whose role is often more circumscribed.

- Application to A's Appointment and Actions:

- Based on the above, the Supreme Court found that A had been validly appointed as a representative director of Company K by the newly elected board on December 27, 1956.

- However, a critical distinction was made: while the provisional disposition remained active and uncancelled, A, even as a validly appointed director and representative director, was still subject to the general restrictions imposed by that disposition on the company's directorial functions. This meant that A could not immediately exercise the full powers of a representative director. Therefore, the initial sale contract A concluded with Company X on January 12, 1957 (while the disposition was still arguably in force against the company's board functions, despite the withdrawal application being imminent) would be ineffective.

- The Turning Point – Withdrawal of the Disposition Application: The factual record indicated that the application for the provisional disposition was formally withdrawn on January 14, 1957. The Supreme Court held that from this point onwards, the restrictions on A's authority effectively ceased. Consequently, A was then free to validly represent Company K and could, therefore, ratify the earlier sale contract with Company X or enter into a new, valid sale agreement.

- Error of the Lower Courts: The Supreme Court concluded that the lower courts had erred in law. They had incorrectly determined that A's appointment as representative director was entirely invalid due to the ongoing (though soon-to-be-lifted) provisional disposition. This led them to wrongly conclude that any subsequent acts of ratification by A were also without effect, without properly considering the legal impact of the withdrawal of the provisional disposition application.

Analysis and Implications: Untangling Corporate Authority

This 1970 Supreme Court decision provided crucial guidance on the complex interplay between provisional court orders, the powers of court-appointed agents, and the authority of newly elected corporate leadership.

- Nature and Evolution of Provisional Dispositions:

The type of provisional disposition discussed (suspending director duties and appointing an agent) is a vital tool in corporate litigation. It's used when there's a pending lawsuit challenging a director's legitimacy (e.g., a suit to nullify their appointment or a suit for their dismissal) and allowing them to continue exercising their powers would be detrimental. Historically, provisions in the Commercial Code (like Article 270) governed these. With the enactment of the Civil Provisional Remedies Act in 1989, such dispositions were clarified as a type of general provisional remedy aimed at fixing a temporary status, subject to the general rules of that Act. The Companies Act (2005) further refined this by incorporating specific provisions for the registration of such orders (Article 917) and defining the powers of provisional agents (Article 352). - Persistence of Provisional Dispositions:

The Supreme Court firmly sided with what was then the majority legal view: a provisional disposition does not automatically cease to be effective merely because the directors who were its initial target resign or are replaced. It remains in force until formally cancelled by a court order, typically upon a showing of a "change in circumstances" that renders the order unnecessary. Minority views had argued for automatic lapsing, but the Court prioritized judicial oversight in terminating such orders. - Powers of Provisional Agents (Shokumu Daikōsha):

Under current law (Companies Act Article 352, Paragraph 1), a provisional agent appointed to perform a director's duties is generally limited to conducting the company's "ordinary affairs" (jōmu), unless the court order specifies otherwise or grants permission for extraordinary acts. "Ordinary affairs" typically refers to the routine, day-to-day operations of the business (e.g., regular purchases of raw materials, sales of products). More significant actions like issuing new shares, issuing bonds, major business transfers, or amending the articles of incorporation are generally considered outside the scope of ordinary affairs and would require court authorization for the agent to undertake. - Authority of Newly Appointed Directors During an Active Disposition:

This judgment offers critical clarification:- The powers of newly appointed directors are generally subordinate to the authority of the provisional agent concerning the company's regular business operations.

- However, the Supreme Court carved out a vital exception: these new directors can validly appoint a representative director if that position is vacant. The Court reasoned that filling this key leadership role is essential for the company's ability to function and is not an act that inherently conflicts with the original purpose of the provisional disposition (which was focused on the specific issues related to the previously suspended directors). Appointing a representative director is a fundamental governance decision, distinct from the day-to-day "ordinary affairs" typically handled by a provisional agent.

- Constraints on the Newly Appointed Representative Director:

A subtle but important point in the judgment is that even if a new representative director (like A) is validly appointed by the new board, they are still subject to the general constraints of the ongoing provisional disposition as long as it remains active. This means that while their appointment is valid, their ability to exercise the powers of a director and representative director is initially restricted. They cannot simply ignore the provisional order that affects the company's directorial functions. - The "Release" Mechanism – Lifting of Restrictions:

The critical event that "released" A from these restrictions was the withdrawal of the application for the provisional disposition. Once this occurred, the legal basis for the constraints on A's directorial and representative directorial authority dissolved, enabling him to act fully on behalf of Company K, including ratifying prior (and hitherto ineffective) agreements. - Ratification of Acts:

The decision implicitly and explicitly supports the principle that acts undertaken by a director or representative director at a time when their authority was suspended (and thus void or ineffective) can be subsequently ratified once their authority is restored or confirmed, provided the ratifying entity (the company acting through its now-authorized representative) has the power to do so.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's November 6, 1970, judgment provides a nuanced and practical framework for understanding the effects of provisional court orders that suspend director duties. It clarifies that such orders do not simply vanish when new directors are appointed; a formal court cancellation based on changed circumstances is generally required. However, the ruling also pragmatically allows newly appointed boards to fill a vacant representative director position, recognizing this as essential for corporate functionality. Most importantly, it underscores that while a validly appointed new representative director may initially be constrained by an ongoing provisional order, the lifting of that order (e.g., by withdrawal of the underlying application) frees them to exercise their full authority, including the power to ratify earlier transactions. This case remains a vital reference for navigating the complexities of corporate governance during periods of internal dispute and court intervention.