Navigating Collective Rebuilding in Japan: The Supreme Court's Stance on Condominium Owner Rights

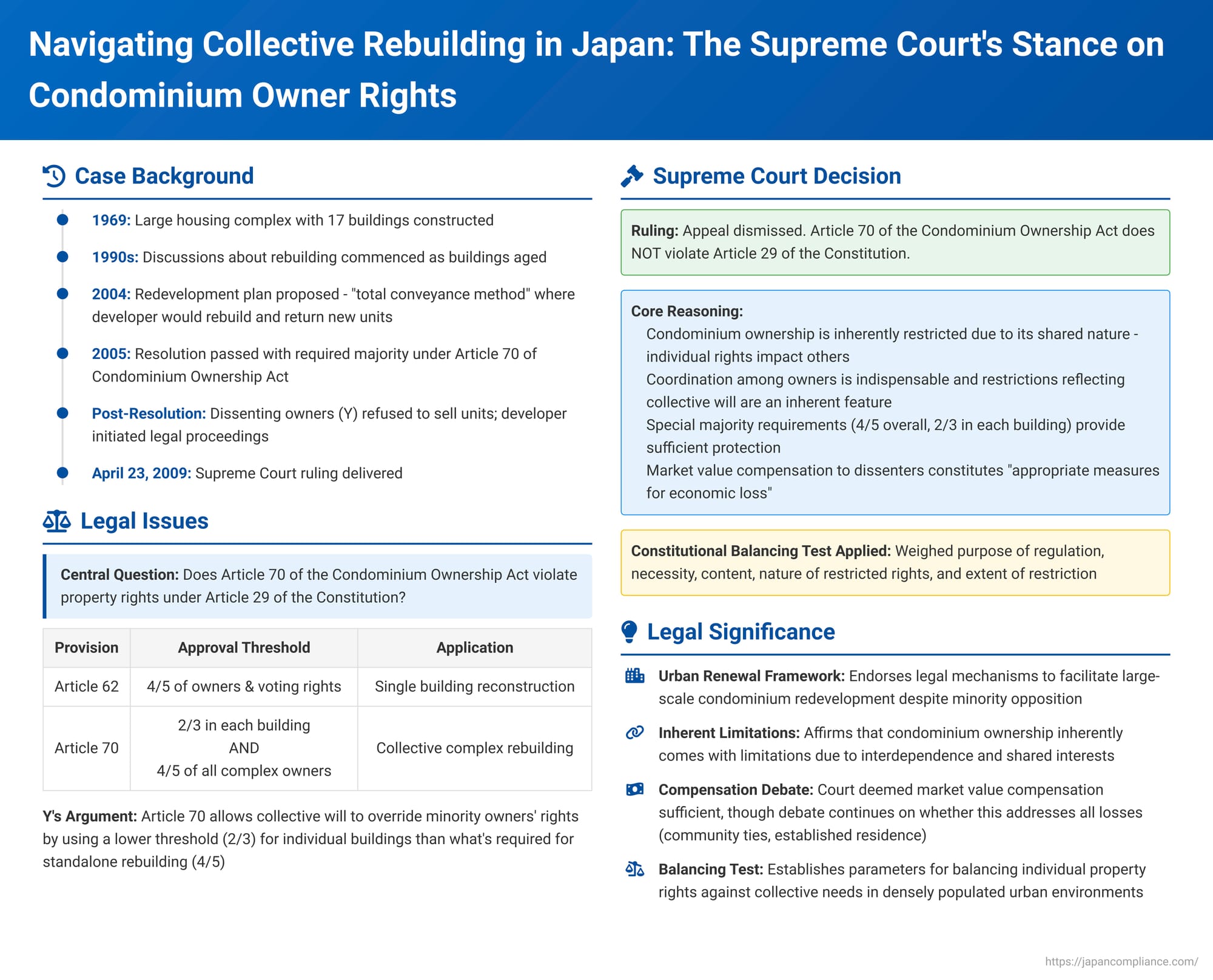

Condominium living is a pervasive feature of Japan's urban landscape. As these structures age, the need for comprehensive redevelopment becomes increasingly pressing. Japan's Act on Unit Ownership of Buildings (often referred to as the Condominium Ownership Act, or Kubu Shoyū Hō) provides legal frameworks to address this, but these processes often highlight a fundamental tension: the collective desire or necessity for rebuilding versus the sacrosanct nature of individual property rights. A pivotal moment in clarifying this balance came with a Supreme Court of Japan decision issued on April 23, 2009, in a case formally titled the Ownership Transfer Registration Procedure Claim Case (Supreme Court, First Petty Bench, Heisei 20 (O) No. 1298). This judgment delved into the constitutionality of legal provisions allowing for the en-bloc reconstruction of entire housing complexes.

I. The Backdrop: An Aging Housing Complex and a Redevelopment Plan

The case originated from a large multi-building housing complex (a danchi) located in Japan. Constructed around 1969, the complex consisted of 17 buildings, all containing privately owned condominium units. The land on which these buildings stood was a single parcel, co-owned by all the unit owners within the complex, and a complex-wide management association, established under its bylaws (kiyaku), oversaw the general administration of the property.

As the decades passed, the buildings naturally aged, and discussions concerning the possibility of a complete rebuilding commenced around 1990. By December 2004, a concrete redevelopment plan was proposed. This plan envisioned a "total conveyance method" (zenbu jōto hōshiki). Under this scheme, each unit owner would transfer their condominium unit ownership (sen'yū bubun) and their corresponding site use rights (shikichi riyōken) to a designated real estate developer, Company X. Company X would then demolish the old structures and construct a new, modern housing complex on the site. Following completion, Company X would transfer ownership of the newly built condominium units and their associated site use rights back to the original unit owners who had agreed to participate in the project. This was structured as an "equivalent exchange project" (tōka kōkan jigyō).

In March 2005, an extraordinary general meeting of the housing complex's management association was held to vote on this collective rebuilding proposal. The resolution was declared passed, having met the specific voting requirements stipulated in Article 70, Paragraph 1 of the Condominium Ownership Act for an "en-bloc collective rebuilding" (danchi'nai zen tatemono ikkatsu tatekae, often shortened to ikkatsu tatekae) of all buildings within the complex.

II. The Dissent and the Legal Battle Commences

Among the residents were individuals, referred to as Y and others, who had lived in the complex for many years. With the exception of one defendant who was the cohabiting partner of a unit owner and not an owner themself, these individuals voted against the rebuilding resolution.

Following the successful passage of the resolution, Company X, having acquired the unit ownership and site use rights from the consenting majority of owners, moved forward with the project. It then exercised its statutory right, as provided under Article 70, Paragraph 4 of the Condominium Ownership Act (which incorporates by reference the provisions of Article 63, Paragraph 4 – now Paragraph 5 – of the same Act). This is the "right to demand sale" (uriwatashi seikyūken), which allows the party spearheading the reconstruction to require dissenting unit owners to sell their units and site use rights at fair market value (jika).

When Y and others refused to sell, Company X initiated legal proceedings, seeking a court order for the transfer of ownership registration for Y's units and their subsequent eviction from the premises. The initial court (District Court) and the first appellate court (High Court) both ruled in favor of Company X, upholding the validity of the rebuilding resolution and the exercise of the right to demand sale. Y and others then appealed this decision to the Supreme Court of Japan.

III. The Core Contention: Constitutionality of Article 70

The central argument advanced by Y and others before the Supreme Court was that Article 70 of the Condominium Ownership Act was unconstitutional, specifically asserting that it violated Article 29 of the Constitution of Japan, which guarantees the right to property.

To understand their challenge, it's important to outline the relevant provisions of the Condominium Ownership Act:

- Article 62, Paragraph 1 (Single Building Reconstruction - Mune Tatekae): This article governs the reconstruction of a single condominium building. It stipulates that such a rebuilding can be resolved at a meeting of that building's unit owners by a majority of at least four-fifths (4/5ths) of both the total number of unit owners and the total number of voting rights.

- Article 70, Paragraph 1 (Collective Complex Reconstruction - Ikkatsu Tatekae): This article, which was the focus of the constitutional challenge, deals with the more complex scenario of rebuilding all buildings within a designated housing complex. It applies when:

- All buildings within the complex contain privately owned units.

- The land for the entire complex is co-owned by all unit owners across all buildings in that complex.

- The complex has established bylaws governing its management.

It sets a two-tiered voting threshold:

- Individual Building Approval: Each separate building within the complex must individually approve the collective rebuilding by a majority of at least two-thirds (2/3rds) of its unit owners and their respective voting rights.

- Overall Complex Approval: The collective rebuilding must also be approved at a general meeting of all unit owners in the entire complex by a majority of at least four-fifths (4/5ths) of the total number of unit owners in the complex and their total voting rights.

The appellants' key complaint about Article 70 was its mechanism: it allowed the collective will of the entire complex, significantly influenced by owners in other buildings, to mandate the reconstruction of a specific building, even if that particular building's owners did not meet the higher 4/5ths approval threshold that would be required if it were undergoing a standalone, single-building reconstruction under Article 62. They argued that this structure disproportionately infringed upon the property rights of the dissenting minority within such a building, and that the Act failed to provide adequate protective measures for these minority owners. The consequence for dissenters, as stipulated by Article 70, Paragraph 4 (applying Article 63, Paragraph 4), was the loss of their ownership and site use rights through a forced sale at market value, which they deemed an insufficient remedy for the loss of their homes.

IV. The Supreme Court's Verdict: Upholding the Law

The Supreme Court delivered its judgment on April 23, 2009.

The Court dismissed the appeal lodged by Y and others. It found that Article 70 of the Condominium Ownership Act does not violate Article 29 of the Constitution.

V. The Court's Rationale: Balancing Interests in Shared Ownership

The Supreme Court laid out its reasoning in a structured manner, addressing the nature of condominium ownership and the legislative aims of the reconstruction provisions.

A. The Inherent Nature of Condominium Ownership:

The Court began by defining unit ownership. It is ownership of a structurally divided, exclusive portion (sen'yū bubun) within a single building (Article 1, Article 2(1), Article 2(3) of the Act). This private ownership is intrinsically tied to shared elements:

- Common Areas (Kyōyō Bubun): Hallways, staircases, and other parts of the building essential for the use of the private units, but not part of any single private unit, are co-owned by all unit owners. Each owner holds a share in these common areas, typically proportionate to the floor area of their private unit, and this share is inseparable from the private unit itself (Article 2(2), 2(4), Article 4, Article 11, Article 14, Article 15).

- Site Use Rights (Shikichi Riyōken): The right to use the land on which the building stands, if it's a co-owned right (like ownership), is also tied to the private unit. Generally, unit owners cannot dispose of their site use right separately from their private unit, unless the complex's bylaws stipulate otherwise (Article 2(6), Article 22).

Given this structure, the Court emphasized that the exercise of one unit owner's rights (including rights related to common areas and the site) inevitably impacts the exercise of rights by other unit owners. Consequently, coordination among unit owners is indispensable. Restrictions on the exercise of individual unit ownership rights, reflecting the collective will of other unit owners (e.g., through resolutions at owners' meetings), are therefore an inherent characteristic of unit ownership itself.

B. Justifying Single-Building Reconstruction (Article 62(1)):

The Court then turned to the provisions for reconstructing a single building. It reasoned that if buildings deteriorate due to aging or other factors, necessitating reconstruction, a situation where a small number of dissenting owners could block the will of a large majority wishing to rebuild would be problematic. Such an impasse would:

- Hinder the securing of a "good and safe living environment."

- Obstruct the "effective utilization of the land."

- Prevent the "reasonable exercise of unit ownership rights" by the majority.

Therefore, Article 62, Paragraph 1, which allows for a single building reconstruction resolution with a 4/5ths majority of unit owners and voting rights, was deemed to possess "sufficient rationality" (jūbun na gōrisei o yūsuru) when considered in light of the inherent nature of unit ownership.

C. Extending the Logic to Collective Complex Reconstruction (Article 70(1)):

The Court then applied similar reasoning to the en-bloc collective reconstruction of an entire housing complex under Article 70, Paragraph 1. It highlighted the objectives of such collective schemes:

- To ensure a "planned good and safe living environment" for the entire complex.

- To achieve "efficient and unified utilization of the entire site."

Regarding the voting thresholds, the Court noted:

- The requirement for the overall complex (4/5ths of all owners and voting rights in the complex) is identical to the threshold for a single-building reconstruction under Article 62(1).

- The requirement for each individual building within the complex (2/3rds of that building's owners and voting rights) constitutes a "majority considerably exceeding a simple majority" (kahansū o sōtō koeru giketsu yōken).

Considering the inherent nature of unit ownership and these specific voting requirements, the Court concluded that the provisions of Article 70, Paragraph 1 "do not lose their rationality" (nao gōrisei o ushinau mono de wa nai).

D. Compensation for Dissenters:

The Court acknowledged that in a collective complex reconstruction, just as in a single-building reconstruction, dissenting unit owners who choose not to participate in the rebuilding face the exercise of the "right to demand sale." This results in them having to sell their unit ownership and site use rights at market value (Article 70(4) applying Article 63(4)). The Court stated that in this regard, "appropriate measures are taken for their economic loss" (sono keizaiteki sonshitsu ni tsuite wa sōō no teate ga sarete iru).

E. The Constitutional Balancing Test:

Finally, the Court explicitly articulated its constitutional assessment. It weighed various factors:

- The purpose of the regulation (Article 70).

- The necessity for such a regulation.

- The content of the regulation.

- The type and nature of the property rights being restricted by the regulation.

- The extent of that restriction.

After this comparative balancing, the Court determined that Article 70 of the Condominium Ownership Act is not in violation of Article 29 of the Constitution (which guarantees property rights). This conclusion, the Court added, was "evident in light of the purport" of a previous Grand Bench decision of the Supreme Court dated February 13, 2002 (Minshū Vol. 56, No. 2, p. 331), a notable case concerning the Securities and Exchange Act.

VI. Deeper Analysis: Unpacking the Court's Reasoning and Its Ramifications

While the Supreme Court's judgment provides a clear legal affirmation, the underlying issues and the nuances of its reasoning invite further examination, drawing from legal commentary and analysis that has developed around this case.

A. The Constitutional Review Standard:

The Supreme Court formally employed a balancing test, a common approach in Japanese constitutional law when assessing restrictions on property rights. This involves weighing the public interest served by the regulation against the severity of the restriction on individual rights. This framework tends to view property rights, including condominium ownership, as rights whose scope and content are defined by legislation, with provisions like Article 70 acting as limitations on these rights.

However, an important undercurrent in the Court's reasoning is the idea that unit ownership is not just a right that can be limited, but a right that is inherently limited by its very nature due to the shared interdependencies. From this perspective, the judicial review focuses more on whether the legislative framework managing these inherent interdependencies—such as reconstruction rules—is itself unreasonable or arbitrary.

It's noteworthy that Article 70 was introduced as part of amendments to the Condominium Ownership Act in 2002. Y and others already owned their units before this amendment. Arguments that the application of this new provision infringed upon their pre-existing, vested rights were made at the lower court levels. The lower courts dismissed these claims, reasoning that the amendments, particularly those facilitating reconstruction in aging buildings, were a legitimate legislative response to a pressing social need and that they, in essence, made explicit the kinds of limitations that were already inherent in the nature of condominium ownership. The Supreme Court, while not directly re-adjudicating this specific point, implicitly accepted this by upholding the law's application.

B. Condominium Ownership: More Than Just Bricks and Mortar:

A crucial dimension, perhaps not fully captured in the direct language of the judgment but essential for a complete understanding, is that condominium units are very often primary residences. They represent the foundation of people's daily lives and are frequently linked to personal dignity, stability, and the ability to maintain a chosen lifestyle and community.

The appellants, Y and others, were not primarily disputing the financial valuation of a commercial asset; their core desire was to continue living in their established homes and community, particularly as they advanced in age. This brings into play considerations that transcend purely economic calculations, touching upon what some might term "housing rights" or the "right to reside." While the concept of a constitutionally guaranteed "right to housing" is less explicitly developed in Japanese jurisprudence compared to some other countries, the profound personal impact of losing one's home is undeniable.

For dissenters, the consequence of a collective rebuilding resolution is not merely a change in investment; it is tantamount to a complete deprivation of their specific property and the established life associated with it. The gravity of this loss arguably calls for an exceptionally careful and detailed level of scrutiny when courts review the laws that enable it.

C. Scrutinizing the "Rationality" of Reconstruction Rules:

The Court's assessment of the "rationality" of Articles 62 and 70 warrants a closer look.

- Single-Building Reconstruction (Article 62): Prior to the 2002 amendments, Article 62(1) included an objective condition for initiating reconstruction, such as when restoring or maintaining the building's utility would entail "excessive expense." This objective requirement was removed by the amendments, making the special majority vote the primary determinant. Some legal scholars contend that, in the absence of such an objective trigger (like demonstrable severe dilapidation or safety hazards), allowing a supermajority to compel reconstruction and force out dissenters could unduly infringe on the dissenters' freedom to use, benefit from, and dispose of their property. This is particularly so if the primary motivation for rebuilding is not urgent necessity but rather a desire for enhanced utility, increased property values, or modernization.

The Supreme Court's justification for Article 62—that preventing reconstruction due to minority dissent hinders a "good and safe living environment" and "effective land use"—is articulated in broad terms. Critics have pointed out that concepts like "good" or "effective" can be subjective evaluations made by the majority and may not always align with a compelling, objectively determined public interest unless directly linked to issues like structural safety. The Court's reasoning does not explicitly preclude reconstructions driven by a desire for increased utility or aesthetic improvement, although some commentators suggest the possibility of a "constitutional narrowing" interpretation, limiting its application to cases where a clear necessity for rebuilding exists.

It is also relevant that the 2002 amendments, while removing the objective requirement, also introduced or enhanced procedural safeguards for reconstruction resolutions (e.g., detailed explanations, Q&A sessions, documented deliberations under Article 62, Paragraphs 4-6). These procedural enhancements could be viewed as a factor contributing to the legitimacy of the decision-making process. - The Unique Challenge of Collective Complex Reconstruction (Article 70): Article 70 presents a more complex scenario because it allows the fate of one building to be significantly influenced by the owners of other buildings within the same complex. This is a departure from the general principle in property law that decisions regarding a specific property (like a building) are primarily made by its direct co-owners. Under Article 70, a building can be slated for reconstruction even if it doesn't achieve the 4/5ths approval from its own owners (as required by Article 62 for a standalone reconstruction), provided it secures a 2/3rds approval from its owners and the overall complex meets the 4/5ths threshold.

The Supreme Court, in this particular judgment, did not extensively delve into this fundamental structural difference between single-building and collective-complex reconstruction. Its reasoning largely mirrored the justification provided for Article 62. However, collective rebuilding under Article 70 serves not only the interests of the majority of owners within a single building but also the broader interest of the majority of co-owners of the entire land parcel who may wish to utilize that land more effectively or comprehensively. This introduces a wider socio-economic policy dimension related to efficient urban land use and planned redevelopment. Explaining the rationality of forcing the reconstruction of a specific building based purely on the "inherent nature of unit ownership" within that single building becomes more intricate in this context.

The Court did specifically mention the individual building threshold of a "majority considerably exceeding a simple majority" (2/3rds) as a component supporting the overall rationality of Article 70. However, the precise legal pathway by which this specific threshold, in tandem with the overall complex vote, is deemed to adequately safeguard the rights of a dissenting minority within an individual building (that might not, on its own, strongly favor reconstruction) is not fully elaborated.

Some legal scholars have noted the subtle difference in the Court's phrasing: Article 62(1) was described as having "sufficient rationality," while Article 70(1) was said to "not lose its rationality." This has led to speculation that the Court might have found the affirmation of Article 70's constitutionality to be a somewhat closer call or a more nuanced issue. If this interpretation holds, a more direct judicial engagement with the unique legal mechanics of Article 70 might have been anticipated by some observers.

D. Is "Market Value" Compensation Truly "Appropriate"?

The Court pointed to the statutory provision that dissenting owners receive market value for their property as evidence that "appropriate measures are taken for their economic loss." This assertion, however, is a focal point of debate.

The critical question is whether monetary compensation, even at fair market value, can genuinely and fully address the spectrum of losses experienced by long-term residents who are compelled to leave their homes. For many individuals, particularly the elderly, those with limited mobility, or those with deep-rooted social and community ties, the value of their home extends far beyond its financial appraisal. It encompasses the right to continued residence in a familiar environment, the stability of their established living arrangements, the proximity of support networks, and intangible sentimental attachments.

Some legal commentaries have argued that a uniform application of "market value" compensation, especially when applied to unit owners who have resided in their property for many years and have no desire to move, might be constitutionally problematic under Article 29, despite the Court's finding. The argument is that "just compensation" in such circumstances might need to consider factors beyond the mere exchange value of the property, potentially including relocation costs, compensation for loss of community, or even a premium for forced displacement.

The appellants (Y and others) had also raised arguments touching upon their right to housing. As noted, the constitutional basis and the precise scope of such a right (e.g., what level of protection it offers against displacement due to lawful redevelopment) remain areas of ongoing jurisprudential development in Japan. It's unclear to what extent such a right, even if more robustly defined, could empower dissenters to halt a reconstruction project that has otherwise met all legal and procedural requirements.

VII. Implications for Future Redevelopment and Legal Interpretation

This Supreme Court decision is a significant endorsement of the legal framework designed to facilitate large-scale condominium redevelopment in Japan. This framework is crucial for addressing the challenges of urban renewal, particularly given the substantial stock of aging condominium buildings constructed during Japan's post-war economic boom.

- Voting Thresholds and Potential Legislative Changes:

- Regarding the overall complex voting requirement (currently 4/5ths under Article 70 for collective rebuilding), the judgment itself offers little specific language that would inherently prevent future legislative discussions about potentially relaxing this threshold. The Court's general deference to legislative judgment on matters of social and economic policy might allow for such changes, provided they are still seen as broadly rational.

- However, concerning the individual building voting requirement within a collective complex scheme (currently 2/3rds), the Court's specific mention of this as a "majority considerably exceeding a simple majority" and as a component contributing to Article 70's rationality is noteworthy. This suggests that any future legislative attempt to significantly reduce this individual building threshold—for instance, to a mere simple majority, or to eliminate it entirely (while perhaps maintaining the overall complex threshold)—could face a more challenging constitutional assessment based on this precedent. Such a reduction might be argued to weaken the protection for minority owners within individual buildings to a degree that is inconsistent with the balance the Court currently views as rational.

The case continues to underscore the persistent and complex tension between the societal need to facilitate necessary urban redevelopment and the imperative to protect the fundamental property rights and housing security of individual homeowners, especially those who may be vulnerable or have profound attachments to their homes and communities.

VIII. Concluding Thoughts: A Balancing Act in an Evolving Urban Landscape

The Supreme Court of Japan's decision of April 23, 2009, concerning Article 70 of the Condominium Ownership Act, stands as a landmark ruling in Japanese property law. It affirms the legislature's authority to establish mechanisms for the collective rebuilding of aging multi-building housing complexes, even in the face of opposition from a minority of owners, provided that specific supermajority voting thresholds are met and that dissenting owners are compensated through the forced sale of their units at market value.

The judgment underscores the distinctive character of condominium ownership as an inherently interdependent form of property. In this model, individual rights are, by necessity, subject to the collective will when exercised for purposes deemed essential for the community, such as ensuring safety, maintaining a good quality living environment, and promoting the efficient and rational use of land.

However, the decision also casts a sharp light on the profound and often life-altering impact that such collective redevelopment actions can have on individuals. For those who dissent, the outcome is frequently the loss not just of a financial asset, but of a home, a community, and an established way of life. While the Supreme Court found the existing legal framework, including the provision for market-value compensation, to be constitutionally sound, the underlying societal and ethical debate about the true adequacy of such compensation—and the broader social justice implications of displacing residents, particularly long-term ones—continues.

This case serves as a critical reference point for understanding the legal and constitutional parameters that shape urban redevelopment in Japan. It reflects a nation grappling with the practical challenges posed by an aging infrastructure and the ongoing imperative to balance the robust protection of private property rights with the evolving collective interests of society in a densely populated and dynamic urban environment. The ruling is indicative of an ongoing effort to adapt legal frameworks to the complex realities of condominium living and the inevitable life cycle of the buildings that define much of Japan's modern urban fabric.