Nationality, Equality, and Social Welfare: The Japanese Supreme Court's Shiomi Decision

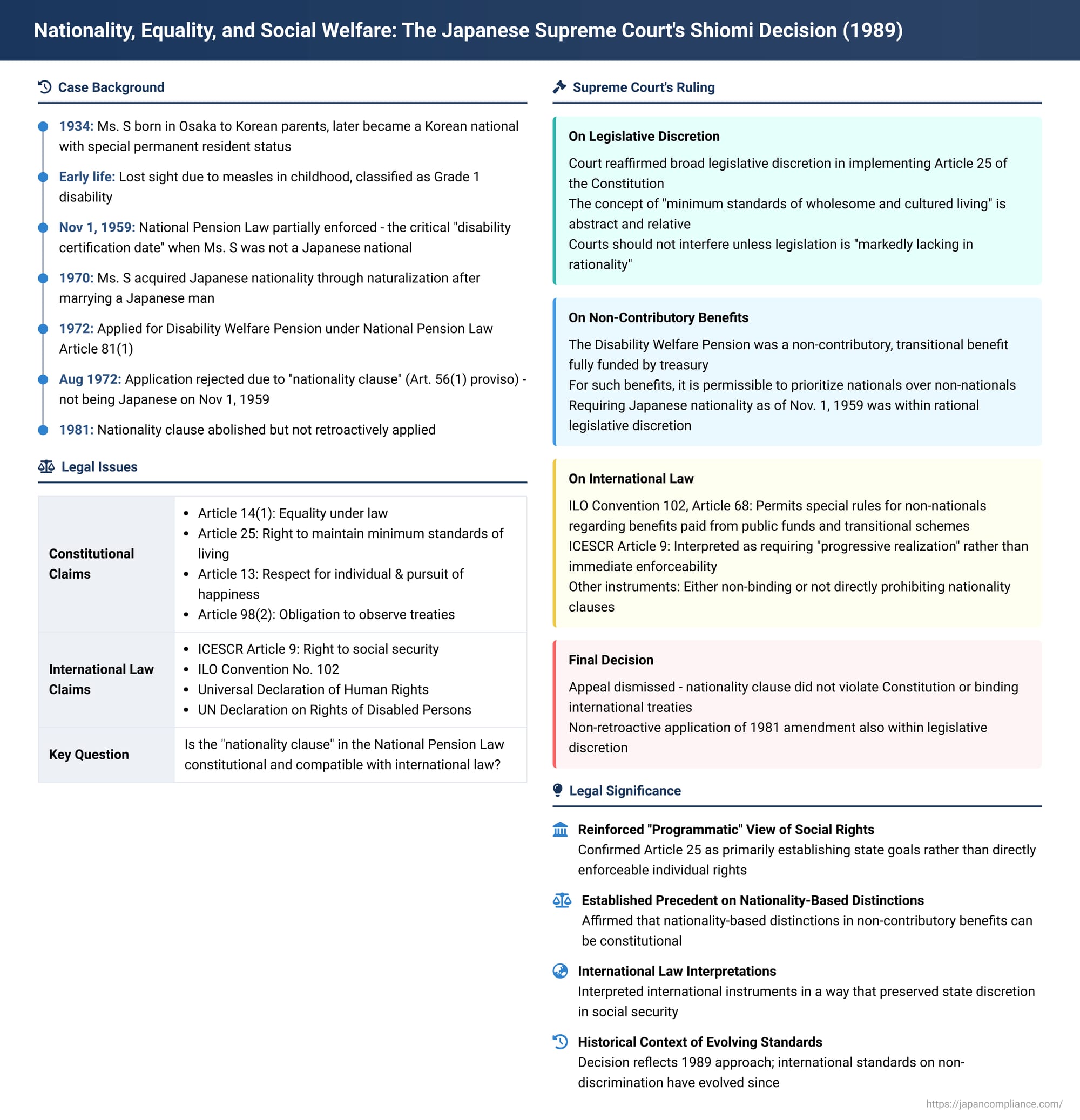

The intersection of nationality, fundamental human rights, and access to social security benefits has been a subject of significant legal debate worldwide. In Japan, the Supreme Court's First Petty Bench delivered a pivotal judgment on March 2, 1989, in the case commonly known as the Shiomi case. This ruling addressed the constitutionality of a "nationality clause" in the National Pension Law, which restricted eligibility for certain disability pensions to Japanese nationals, and its compatibility with international human rights standards. The case highlights the complexities faced by long-term foreign residents, particularly those with deep historical ties to Japan, in accessing social welfare.

The Personal History and Plight of Ms. S

The appellant, Ms. S, was born in Osaka, Japan, in 1934 to parents of Korean ethnicity. Following the end of World War II and the subsequent San Francisco Peace Treaty, various administrative measures by the Japanese government led to individuals of Korean and Taiwanese heritage, who had previously been Japanese nationals, losing their Japanese nationality. Ms. S thus became a Korean national, holding the status of a special permanent resident in Japan. Later in life, she married a Japanese man and, in 1970, acquired Japanese nationality through the process of naturalization.

Tragically, Ms. S had lost her sight in childhood due to measle. As of November 1, 1959—a critical date marking the partial enforcement of the National Pension Law (pre-1981 amendment)—she was already in a state of severe disability, classified as Grade 1 under the then-existing legal framework (the term "廃疾" - haishitsu, meaning disabling condition, was later changed to "障害" - shōgai, meaning disability.

In 1972, Ms. S applied for a Disability Welfare Pension (障害福祉年金 - shōgai fukushi nenkin) under Article 81, Paragraph 1 of the National Pension Law in effect at the time. This particular pension was a non-contributory, transitional benefit designed for individuals who were already disabled when the pension system was launched. However, in August 1972, the Governor of Osaka Prefecture (the appellee) rejected her application. The reason cited was a specific provision in the National Pension Law—Article 56, Paragraph 1, proviso (commonly referred to as the "nationality clause" or 国籍条項 - kokuseki jōkō)—which stipulated that individuals who were not Japanese nationals on the "disability certification date" (廃疾認定日 - haishitsu ninteibi) were not eligible for this pension. For this transitional pension, the disability certification date was fixed as November 1, 1959, a date on which Ms. S was a Korean national.

The Legal Challenge: From Administrative Appeals to the Supreme Court

Ms. S contested this decision through the available administrative appeal channels, but her claims were dismissed. She then filed a lawsuit seeking the revocation of the disposition, arguing that the nationality clause in the National Pension Law violated several provisions of the Japanese Constitution: Article 13 (respect for the individual and right to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness), Article 14, Paragraph 1 (equality under the law), and Article 25 (the right to maintain minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living, and the state's duty to promote social welfare).

Despite her arguments, both the court of first instance and the appellate court dismissed her claims. Ms. S then appealed to the Supreme Court of Japan. In her appeal, she contended that restricting the application of the social security system to Japanese nationals, and thereby excluding resident foreigners—especially those like Zainichi Koreans with unique historical and social reasons for residing in Japan—was contrary to historical trends and international legal norms. She asserted that such exclusion violated Article 98, Paragraph 2 (the obligation to faithfully observe treaties), Article 25, and Article 14 of the Constitution.

Ms. S specifically highlighted several international instruments that, she argued, underscored the principle of equal treatment for nationals and non-nationals in social security. These included:

- Articles 22 and 25(1) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR).

- Article 9 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR).

- ILO Convention No. 102 (Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention).

- ILO Convention No. 118 (Equality of Treatment (Social Security) Convention).

- The UN Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons.

- The Refugee Convention.

It is pertinent to note that the nationality clause in the National Pension Law was indeed abolished in 1981, partly in connection with Japan's accession to the Refugee Convention. However, a supplementary provision to the amending law stipulated that non-payment of welfare pensions under the old law would continue to be governed by the previous rules ("なお従前の例による"), meaning the abolition did not retroactively benefit Ms. S.

The Supreme Court's Judgment: Upholding Legislative Discretion

On March 2, 1989, the First Petty Bench of the Supreme Court delivered its judgment, ultimately dismissing Ms. S's appeal. The Court meticulously addressed her constitutional and international law arguments.

1. The Nationality Clause and Article 25 (Right to Social Security)

The Court first considered whether the nationality clause and the consequent denial of the pension to Ms. S (who naturalized after the 1959 certification date) violated Article 25 of the Constitution.

- Nature of Article 25: The Court reiterated its established jurisprudence that Article 25, which declares the state's duty to ensure all citizens can maintain "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" and to endeavor to promote and extend social welfare and security, sets forth a state responsibility based on the ideals of a welfare state. However, Article 25(1) does not directly confer concrete, legally enforceable rights upon individual citizens against the state. Rather, concrete rights to a minimum standard of living are to be established and developed through legislative measures and social institutions, as mandated by Article 25(2).

- Abstract Nature of "Minimum Standards": The concept of "minimum standards of wholesome and cultured living" is inherently abstract and relative. Its specific content is to be determined in correlation with the prevailing level of cultural development, economic and social conditions, and the general living standards of the populace at any given time.

- Legislative Discretion: When the Diet (Japan's legislature) translates the objectives of Article 25 into actual legislation, it cannot ignore the nation's financial situation and must undertake multifaceted, complex considerations leading to policy-based judgments. Therefore, the choice and determination of what specific legislative measures to enact are entrusted to the broad discretion of the legislature. Courts should not interfere with these legislative decisions unless they are found to be "markedly lacking in rationality" or constitute a "clear deviation from or abuse of discretionary power".

- Nature of the Specific Pension: The Disability Welfare Pension under Article 81(1) of the (old) National Pension Law was a non-contributory pension, fully funded by the national treasury. It was established as a transitional relief measure at the inception of the national pension system for individuals who were already disabled or elderly, or who could not meet the contribution requirements of the primary insurance-based scheme. Given this non-contributory and transitional nature, the legislature possessed inherently broad discretion in determining the scope of its beneficiaries.

- Treatment of Resident Foreigners in Social Security: The Court stated that, in the absence of specific treaties, how a state treats resident foreign nationals within its social security policies is a matter for its political judgment. This judgment can be based on factors such as diplomatic relations with the foreigner's country of origin, the evolving international situation, and domestic political, economic, and social circumstances. Crucially, the Court held that when providing welfare benefits from limited financial resources, it is permissible for a state to prioritize its own nationals over resident foreign nationals.

- Application to the Nationality Clause: Based on these considerations, the Court concluded that excluding resident foreign nationals from the scope of this particular Disability Welfare Pension fell within the permissible range of legislative discretion. Furthermore, requiring Japanese nationality as of the specific "disability certification date" (November 1, 1959, the system's inception date) for this transitional benefit was not deemed to lack rationality. The Court also added that whether to enact special relief measures, such as treating individuals who naturalized after this date as if they had been Japanese nationals retroactively, or applying the effects of the later 1981 NPL amendment (which abolished the nationality clause) retrospectively, was fundamentally a matter for legislative discretion.

- Conclusion on Article 25: Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the nationality clause and the denial of the Article 81(1) Disability Welfare Pension to individuals who acquired Japanese nationality after November 1, 1959, did not violate the provisions of Article 25 of the Constitution. The Court found this conclusion to be in line with its previous Grand Bench rulings, including the 1978 MacLean case (concerning foreigner's rights and visa renewal) and a 1982 case (Asahi v. Japan, concerning the level of public assistance).

2. The Nationality Clause and Article 14, Paragraph 1 (Equality Under the Law)

Next, the Court addressed the argument that the nationality clause and its application violated Article 14, Paragraph 1, which guarantees equality under the law.

- Principle of Equality: Article 14(1) prohibits discrimination without reasonable grounds. However, it does not forbid all forms of differential treatment. Making distinctions in legal treatment based on existing economic, social, or other factual differences among individuals is permissible as long as such distinctions are rational.

- Rationality of the Distinction: In the context of the Article 81(1) Disability Welfare Pension, a distinction was made between those who held Japanese nationality on the disability certification date and those who did not. The Court reiterated its earlier points: prioritizing Japanese nationals over resident foreigners for this type of non-contributory, transitional benefit, and establishing Japanese nationality on the system's inception date (November 1, 1959) as an eligibility requirement, were matters falling within the legislature's discretionary powers.

- Conclusion on Article 14(1): Therefore, the Court found that the rationality of this differential treatment could not be denied, and consequently, it did not violate Article 14, Paragraph 1 of the Constitution.

3. The Nationality Clause and Article 98, Paragraph 2 (Observance of Treaties)

Finally, the Supreme Court examined whether the nationality clause violated Article 98, Paragraph 2 of the Constitution, which requires Japan to faithfully observe treaties it has concluded and established international law.

- ILO Convention No. 102 (Social Security (Minimum Standards) Convention, 1952): Ms. S argued that the nationality clause contravened this treaty. Article 68(1) of ILO Convention No. 102 generally states that "Non-national residents shall have the same rights as national residents." However, the Court pointed to a crucial proviso in the same article: "Provided that special rules concerning non-nationals and nationals born outside the territory of the Member may be prescribed by national laws or regulations in respect of benefits or portions of benefits which are payable wholly or mainly out of public funds and in respect of transitional schemes." Since the Disability Welfare Pension in question was entirely funded by the national treasury and was a transitional measure, the Court concluded that the nationality clause did not violate ILO Convention No. 102.

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR): Article 9 of the ICESCR states that "The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to social security, including social insurance." The Supreme Court interpreted this provision not as establishing an immediately enforceable, concrete right for individuals to claim specific benefits, but rather as a declaration by States Parties of their political responsibility to confirm that the right to social security deserves protection under national social policy and to actively promote social security policies towards the realization of this right. The Court found support for this interpretation in Article 2, Paragraph 1 of the ICESCR, which obliges States Parties "to take steps... by all appropriate means, including particularly legislative measures, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant." The progressive nature of this obligation implied, in the Court's view, that the ICESCR was not intended to immediately invalidate nationality clauses like the one at issue.

- Other International Instruments:

- ILO Convention No. 118 (Equality of Treatment (Social Security) Convention, 1962): The Court noted that Japan had not ratified this convention at the time of the judgment.

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), UN Declaration on the Rights of Mentally Retarded Persons, UN Declaration on the Rights of Disabled Persons, and related ECOSOC resolutions: The Court characterized these instruments as expressions of the views of the United Nations or its organs, which are not legally binding on member states.

- Conclusion on Article 98(2): Since the cited international instruments were either not legally binding on Japan or, if binding (like ILO 102 and ICESCR), were not interpreted by the Court as directly prohibiting the nationality clause in this specific context, the appellant's argument that the clause violated Article 98(2) by conflicting with these instruments was deemed to lack its essential premise.

Based on this reasoning across all constitutional and international law points, the Supreme Court upheld the lower court's decision as legitimate and dismissed Ms. S's appeal.

Key Principles, Implications, and the Evolving Context

The Shiomi case is a significant judgment in Japanese constitutional law, particularly concerning social rights and the legal status of foreign nationals. Several key principles and implications emerge:

- Legislative Discretion in Social Welfare: The decision strongly reinforces the principle of broad legislative discretion in designing and implementing social security programs. The Court showed considerable deference to the Diet's policy choices, especially for non-contributory, transitional benefits funded by the state.

- "Programmatic" Nature of Socio-Economic Rights: The Court's interpretation of Article 25 of the Constitution and Article 9 of the ICESCR as primarily "programmatic"—setting goals for the state rather than granting directly enforceable individual rights to specific benefits—has been a consistent feature of Japanese jurisprudence on socio-economic rights. This approach limits the scope for direct judicial intervention in welfare distribution policies.

- Permissibility of Prioritizing Nationals: The judgment explicitly permits the state, when distributing welfare benefits from limited public funds, to prioritize its own nationals over resident non-nationals, particularly in the absence of specific treaty obligations mandating equal treatment for the benefit in question. This was justified by the nature of the non-contributory pension and the state's general discretion in determining the treatment of foreigners.

- The "Nationality Clause" in Historical Context: The case sheds light on the historical use of nationality clauses in Japan's social security system, particularly in its early, transitional phases. While the specific clause in the National Pension Law was abolished in 1981, its non-retroactive application meant that individuals like Ms. S, who were affected by it before the amendment, could not benefit from the change for past periods.

The Evolving International Human Rights Landscape:

It is worth noting that while the Shiomi judgment reflects the Supreme Court's stance in 1989, international human rights law and its interpretation continue to evolve. For instance, the commentary accompanying the case presentation notes that the ICESCR's non-discrimination provision (Article 2(2)) is considered an immediate obligation, applicable irrespective of the progressive realization of other rights. This suggests that any legislative measure concerning social security, even if part of a progressively realized system, should not be discriminatory from the outset. Similarly, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which Japan has also ratified, contains a strong non-discrimination clause (Article 26) applicable to all legislative fields, including social security.

Furthermore, jurisprudence in other regions, such as that of the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR), has increasingly scrutinized nationality-based distinctions in social security. The ECtHR has moved towards requiring "weighty reasons" to justify such distinctions, especially for long-term, stable residents, and has downplayed the relevance of whether a scheme is contributory or non-contributory when assessing discrimination. While these evolving international standards did not alter the outcome of the Shiomi case, they form an important part of the broader legal context for understanding issues of equality and social security for non-nationals.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's decision in the Shiomi case on March 2, 1989, remains a critical reference point in Japanese law regarding the scope of social security rights for individuals, the principle of equality, and the treatment of foreign nationals. By upholding the Diet's broad discretion in structuring non-contributory, transitional welfare benefits and permitting the prioritization of Japanese nationals under specific historical conditions, the Court underscored a cautious approach to the judicial enforcement of socio-economic rights and the application of international human rights norms in this domain. The case continues to inform discussions about the balance between national sovereignty, legislative policy choices in social welfare, and the imperative of ensuring fair and equal treatment for all residents.