Nationality at Birth for Recognized Children: A Japanese Supreme Court Solution for Legal Loopholes

Date of Judgment: October 17, 1997

Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

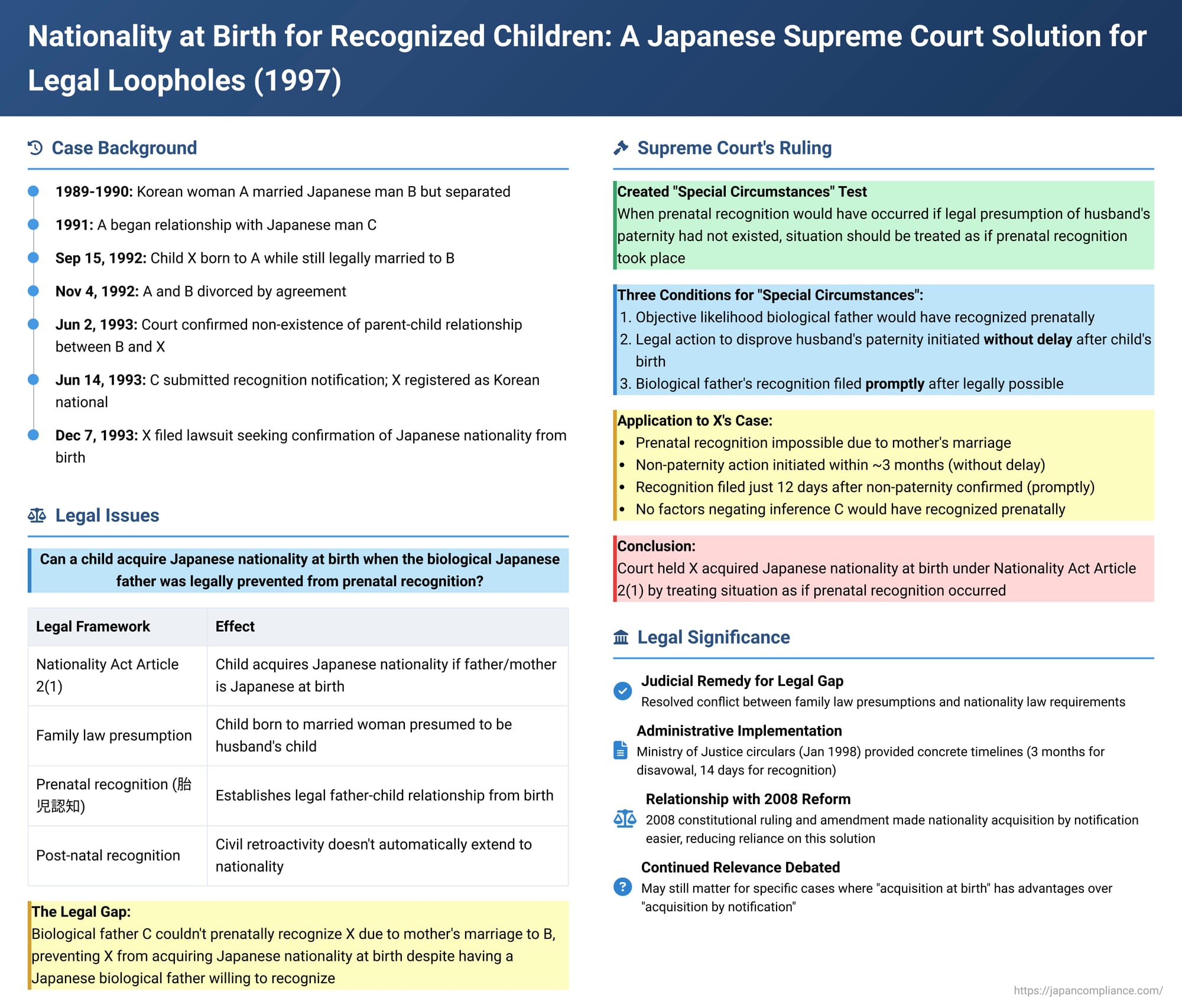

Japan's Nationality Act primarily follows the principle of jus sanguinis (nationality by descent), meaning a child generally acquires Japanese nationality if one or both parents are Japanese citizens. However, complex family situations, particularly involving presumptions of legitimacy under family law, can create unintended hurdles for children of Japanese fathers and foreign mothers. A significant Supreme Court decision on October 17, 1997, addressed such a scenario, crafting a judicial solution to ensure that children were not unfairly denied Japanese nationality at birth due to technical impediments to prenatal recognition by their biological Japanese fathers.

The Factual Background: A Child Caught Between Presumptions and Biology

The case involved a child, X, born under complicated family circumstances:

- A (Mother): A Korean national. She married B, a Japanese man, in 1989 but they separated in 1990.

- C (Biological Father): Another Japanese man, with whom A became acquainted around 1991.

- X (Child): Was born to A on September 15, 1992. At the time of X's birth, A was still legally married to B, although separated.

- Divorce and Paternity Disavowal: A and B formally divorced by agreement on November 4, 1992 (shortly after X's birth). Subsequently, conciliation proceedings were initiated to confirm the non-existence of a legal parent-child relationship between B (A's former husband) and X, due to the presumption of legitimacy that would otherwise apply. This non-existence was judicially confirmed, becoming final on June 2, 1993.

- Recognition by Biological Father and Birth Notification: On June 14, 1993 (twelve days after B's non-paternity was finalized), C, the biological Japanese father, submitted a notification of recognition for X. On the same day, A submitted X's birth notification. However, the father's column on the birth notification (which might have initially indicated B) was struck out, and X's nationality was officially recorded as "Korean."

- X's Lawsuit: Consequently, on December 7, 1993, X (represented by a legal guardian) filed a lawsuit against Y (the State of Japan), seeking a court declaration confirming X's Japanese nationality from birth.

The Tokyo District Court (first instance) dismissed X's claim, emphasizing that nationality by birth should be determined definitively based on the legal parent-child relationship existing at the precise moment of birth. The Tokyo High Court, however, reversed this decision. It reasoned that in "extremely exceptional cases" like this—where prenatal recognition by the biological father C was practically impossible due to the presumption of B's paternity, but where B's non-paternity was swiftly established and C's recognition immediately followed—the requirements of Nationality Act Article 2(1) could be deemed met. The High Court stressed this was not a general endorsement of retroactive nationality acquisition via post-natal recognition but a specific interpretation for unique circumstances to prevent prolonged uncertainty. The State then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Legal Conundrum: A Blocked Path to Nationality by Birth?

The core of the problem lay in the interaction between Japan's family law (specifically, presumptions of paternity) and its nationality law:

- Nationality Act Article 2(1): This article states that a child shall be a Japanese national if, at the time of their birth, their father or mother is a Japanese national. For a child of a non-Japanese mother to acquire nationality through a Japanese father under this provision at birth, a legal father-child relationship must exist at the moment of birth.

- Prenatal Recognition (胎児認知 - taiji ninchi): If a Japanese man recognizes a child in utero (before birth), this establishes the legal father-child relationship from the moment of birth, allowing the child to acquire Japanese nationality under Article 2(1).

- The Impediment: When a child is born to a married woman, Japanese family law (and registration practices) presumes the child to be the legitimate child of her husband. In such cases, it is generally not possible for another man (even the biological father) to file a prenatal recognition, as it would conflict with this legal presumption. This effectively blocked C's ability to prenatally recognize X, thereby preventing X from automatically acquiring Japanese nationality at birth through C.

- Post-Natal Recognition: While C did recognize X after B's non-paternity was confirmed, Japanese law (as understood at the time and affirmed by the Supreme Court in later cases) generally holds that the retroactive effect of post-natal recognition under the Civil Code (Article 784, stating recognition is retroactive to birth for civil law purposes) does not automatically extend to grant Japanese nationality from birth under Article 2(1) of the Nationality Act. Other pathways for post-birth nationality acquisition, like Article 3 of the Nationality Act, had their own distinct requirements (which, at the time, included legitimation through parental marriage—a rule later found unconstitutional in 2008, as discussed in case file is108.pdf).

This created a situation where a child like X, despite having a biological Japanese father willing to acknowledge paternity, was effectively barred from acquiring Japanese nationality at birth simply due to the mother's marital status at the time of conception and birth.

The Supreme Court's Solution: Deeming Prenatal Recognition Under "Special Circumstances"

The Supreme Court dismissed the State's appeal, thereby affirming X's Japanese nationality from birth. It did so by crafting a specific interpretive solution:

- Addressing the Discrepancy: The Court highlighted the unreasonable discrepancy created by the interaction of family law presumptions and nationality law. A child of a foreign mother and a Japanese biological father could acquire Japanese nationality at birth if the mother was unmarried (allowing for prenatal recognition), but would be denied this route if the mother was married to another man at the time, even if the biological father's intent and the child's genetic link to Japan were identical. The Court found such a stark difference based on the "vagaries of the family register" to be difficult to justify.

- The "Special Circumstances" Test: To ensure a more equitable outcome and provide a path to nationality in such cases, the Supreme Court ruled that Nationality Act Article 2(1) should be rationally interpreted and applied. It held that:

If "special circumstances exist where it should be recognized that prenatal recognition by the Japanese father would have occurred if, objectively viewed, the presumption of legitimacy by the husband under the family register had not existed," then the situation should be treated as if such prenatal recognition had indeed taken place. - Conditions Defining "Special Circumstances": For these "special circumstances" to be met, thereby allowing nationality acquisition under Article 2(1) by analogy to prenatal recognition, the Court laid out strict conditions, emphasizing the desirability of determining nationality definitively and as close to birth as possible:

- Objective Likelihood of Prenatal Recognition: It must be objectively apparent that, but for the legal impediment of the presumption of the husband's paternity, the biological Japanese father would have prenatally recognized the child.

- Prompt Legal Action to Disprove Husband's Paternity: Legal proceedings to establish the non-existence of a parent-child relationship between the mother's husband and the child must have been initiated without delay (遅滞なく - chitai naku) after the child's birth.

- Prompt Recognition by Biological Father: After the husband's non-paternity was legally confirmed and it became legally possible for the biological father to recognize the child, the notification of recognition by the biological father must have been filed promptly (速やかに - sumiyaka ni).

- Application to X's Case: The Supreme Court found that these conditions were met in X's situation:

- Prenatal recognition by C was factually impossible due to the presumption of B's paternity.

- Legal action to confirm B's non-paternity was initiated within approximately three months of X's birth ("without delay").

- C's recognition of X was filed just 12 days after B's non-paternity was finalized ("promptly").

- There were no other circumstances negating the inference that C would have prenatally recognized X if legally able.

- Conclusion: The Court held that these facts constituted the requisite "special circumstances." Therefore, X was deemed to have acquired Japanese nationality at birth under Article 2(1) of the Nationality Act, by analogy to a situation where prenatal recognition had occurred.

Significance and Subsequent Developments

This 1997 Supreme Court decision was highly significant:

- Judicial Remedy for a Legal Gap: It provided an important judicial remedy for children in a specific, challenging legal predicament, ensuring they were not unfairly denied Japanese nationality due to the interplay of family law presumptions and nationality law requirements.

- Administrative Guidance: Following this ruling, Japan's Ministry of Justice issued administrative circulars (e.g., on January 30, 1998) to guide family register officials. These circulars adopted the Supreme Court's "special circumstances" test and provided more concrete timelines (e.g., generally, initiating disavowal proceedings within 3 months of birth and filing recognition within 14 days of the non-paternity judgment becoming final) as benchmarks for satisfying the "without delay" and "promptly" requirements.

- Impact of the 2008 Nationality Act Amendment: A subsequent landmark Supreme Court Grand Bench decision in 2008 (related to case file is108.pdf) declared the "legitimation requirement" in Article 3(1) of the Nationality Act unconstitutional. This led to a legislative amendment in December 2008, which made it easier for children born out of wedlock to a Japanese father and a non-Japanese mother to acquire Japanese nationality by notification after birth, regardless of parental marriage.

- Continuing Relevance of the 1997 Ruling?: Academic commentary, as noted by Professor Kunimoto, has debated the ongoing relevance of this 1997 "special circumstances" ruling after the 2008 reforms to Article 3.

- Some argue it may still be relevant in very specific, exceptional cases, particularly if there's a strong reason why "acquisition at birth" under Article 2(1) (via the 1997 ruling's logic) is preferred over "acquisition by notification" under the reformed Article 3 (e.g., potential implications for dual nationality under foreign laws).

- Others, including Professor Kunimoto, suggest that the 1997 ruling's "strained interpretation" was a necessary measure to address a "legislative deficiency" that has now been largely rectified by the reformed Article 3, making the 1997 approach less necessary or perhaps even problematic due to its textual stretch and potential to grant nationality at birth based on a post-natal act without the mother's direct consent at the time of birth.

Conclusion

The 1997 Supreme Court decision concerning post-natal recognition and nationality by birth stands as a notable example of judicial interpretation aimed at achieving fairness and resolving a specific legal anomaly. By creating a pathway for children born into complex family registration situations to acquire Japanese nationality from birth under "special circumstances," the Court sought to prevent an unjust outcome based on technical legal impediments. While subsequent legislative changes to the Nationality Act have provided more direct routes for many children in similar situations, this case remains an important illustration of the judiciary's role in interpreting and applying law in a manner that aligns with fundamental principles of reasonableness and seeks to protect the interests of children caught in the intricacies of legal systems.