National Health Insurance Premiums and Japan's Constitution: The Asahikawa Case

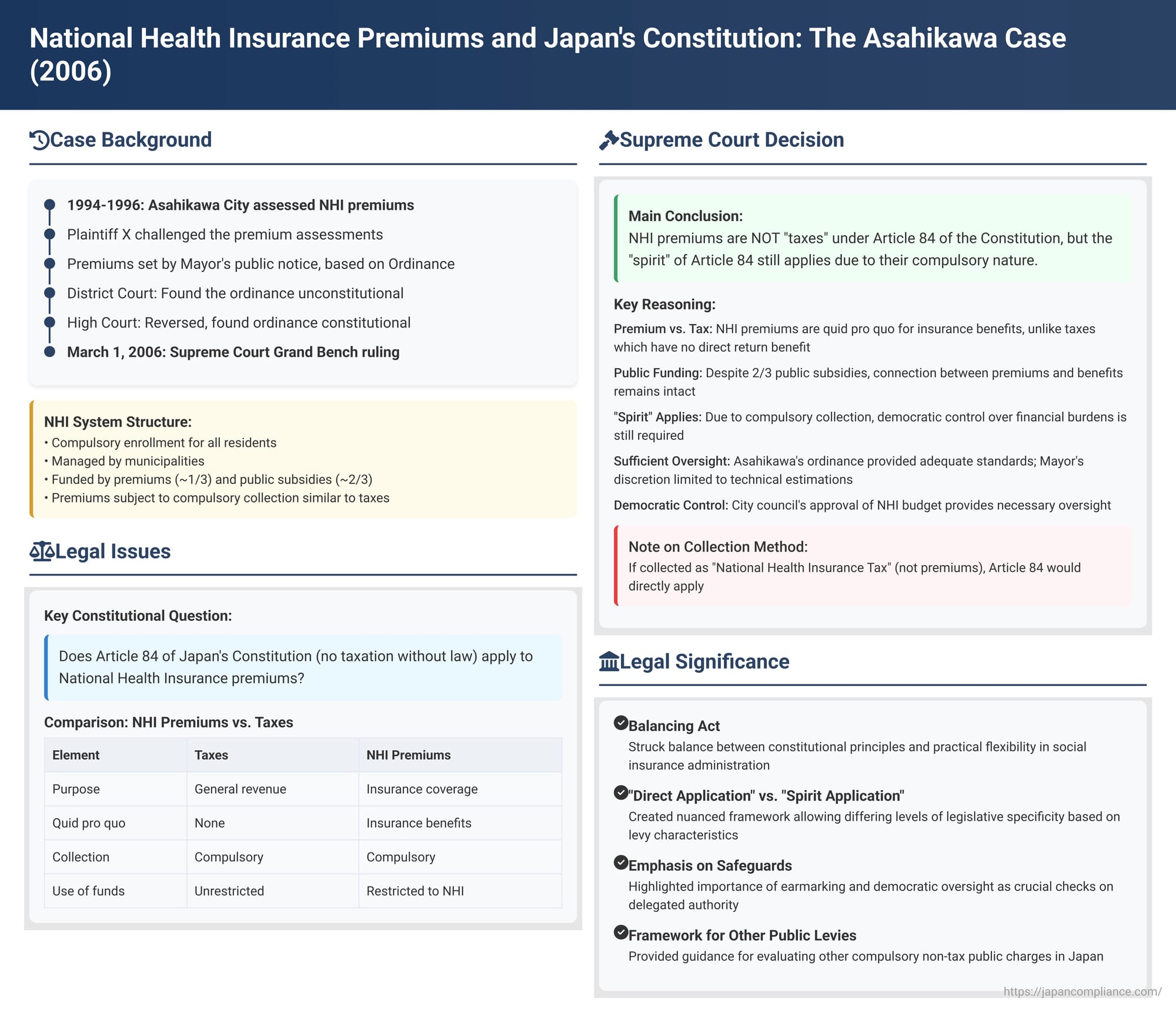

On March 1, 2006, the Grand Bench of the Supreme Court of Japan delivered a pivotal judgment in a case originating from Asahikawa City. The ruling addressed a fundamental question: do National Health Insurance (NHI) premiums, and the way their rates are determined by local governments, fall under the strict constitutional principle of "no taxation without law"? This decision has significant implications for how social insurance schemes are funded and administered in Japan, balancing the need for compulsory public welfare programs with democratic control over financial burdens.

Understanding National Health Insurance (NHI) in Japan

Japan's National Health Insurance system is a cornerstone of its universal healthcare coverage. Here's a brief overview of its key features relevant to the Asahikawa case:

- Purpose: NHI is a social insurance system designed to ensure access to medical care for all citizens. Its aim is to promote social security and public health.

- Management: Municipalities, such as Asahikawa City in this case, act as insurers and manage the NHI program for their residents.

- Compulsory Enrollment: Individuals residing in a municipality who are not covered by other employee-based health insurance schemes are generally required to enroll in the NHI program offered by their local municipality.

- Funding Structure: The NHI system is funded through a combination of sources:

- Premiums: Collected from the head of the household for insured members.

- Government Subsidies: Significant financial contributions are made from national government funds (負担金 - futankin, 調整交付金 - chōsei kōfukin, 補助金 - hojokin), as well as from prefectural and municipal general accounts. In the Asahikawa City case, for the fiscal years in question (1994-1996), premium income constituted about one-third of the NHI special account's total revenue, with public funds covering the remaining two-thirds.

- Premiums vs. NHI Tax: Municipalities have the option to collect these contributions either as "insurance premiums" (保険料 - hokenryō) or as an earmarked "National Health Insurance tax" (国民健康保険税 - kokumin kenkō hoken zei). Asahikawa City had chosen the premium collection method.

- Compulsory Collection: NHI premiums are subject to compulsory collection. If a household fails to pay by the designated deadline after receiving a demand notice, the municipality can take measures similar to those for delinquent local taxes, potentially including the seizure of assets.

The Legal Challenge in Asahikawa City

The case was brought by Plaintiff X, a head of household and an insured member of the NHI program administered by Asahikawa City. X challenged the legality of the NHI premium assessments imposed by the city for fiscal years 1994, 1995, and 1996.

The core of X's argument revolved around Article 84 of the Constitution of Japan, which states: "No new taxes shall be imposed or existing ones modified except by law or under such conditions as law may prescribe." This is commonly understood as the principle of "no taxation without law" (or, for local governments, "no taxation without ordinance").

X contended that the Asahikawa City National Health Insurance Ordinance (hereafter "the Ordinance") violated this principle. While the Ordinance laid out the method for calculating NHI premiums, it delegated the authority to determine the actual premium rates for each fiscal year to the Mayor of Asahikawa. These rates were then announced via a mayoral public notice (告示 - kokuji). X argued that this delegation was too broad and lacked the requisite clarity and direct legislative basis mandated by the spirit of Article 84, effectively making the premiums an arbitrary imposition.

The Journey Through the Lower Courts

- Asahikawa District Court (First Instance): The District Court sided with Plaintiff X. It found that NHI premiums, due to their compulsory nature and the significant reliance on public funds, were substantially similar to taxes. Therefore, the strict principle of "no taxation without ordinance" (租税条例主義 - sozei jōrei shugi) should apply. The court held that while an ordinance could delegate rate-setting, the fundamental criteria, particularly the method for determining the total amount to be assessed (賦課総額 - fuka sōgaku), were not defined with sufficient clarity in the Ordinance itself. This, the court concluded, gave the city excessive discretion and violated the constitutional requirement.

- Sapporo High Court (Second Instance): The High Court reversed the District Court's decision. It reasoned that NHI premiums are essentially a quid pro quo (反対給付 - hantai kyūfu) for receiving insurance benefits, distinguishing them from taxes, which are not tied to a specific return benefit. Thus, Article 84 of the Constitution does not directly apply to NHI premiums. However, the High Court acknowledged that because premium collection is compulsory, the spirit or purport (趣旨 - shushi) of Article 84, which aims to ensure democratic control over financial burdens, does extend to them. Unlike taxes, the court found it permissible for an ordinance to establish the general framework for premium assessment and delegate the setting of specific rates to subordinate regulations, provided the ordinance itself contains clear and concrete standards for this calculation. The High Court determined that Asahikawa's Ordinance met this standard.

Plaintiff X appealed this decision to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (Grand Bench)

The Grand Bench of the Supreme Court, in its judgment of March 1, 2006, ultimately dismissed X's appeal, upholding the High Court's conclusion but providing a more detailed constitutional analysis.

NHI Premiums vs. Taxes under Article 84

- The Court first defined what constitutes a "tax" for the purposes of Article 84 of the Constitution. It stated that a tax is a monetary charge imposed by the state or a local public entity based on its taxing power to raise funds for its expenses. Crucially, it is not levied as a quid pro quo for a special service or benefit but is imposed on all persons who meet certain defined criteria.

- Applying this definition, the Court ruled that NHI premiums are different from taxes. They are collected as a consideration or quid pro quo for the insured person's eligibility to receive insurance benefits under the NHI system.

- The Court acknowledged that in Asahikawa's case, approximately two-thirds of the NHI program's expenses were covered by public funds (national and local government contributions). However, it held that this substantial public subsidy does not sever the inherent connection (牽連性 - kenrensei) between the premiums paid by the insured and their status of being eligible to receive benefits.

- The compulsory enrollment in NHI and the compulsory collection of premiums, the Court explained, are derived from the fundamental nature and purpose of NHI as a social insurance system. These features are designed to include as many eligible individuals as possible within the insurance pool to effectively share risks and distribute the financial burden of medical expenses among all members.

- Based on this reasoning, the Supreme Court concluded that Article 84 of the Constitution does not directly apply to NHI premiums.

- As an important aside, the Court noted that if a municipality chooses to collect NHI contributions in the form of a tax (i.e., as "National Health Insurance Tax"), then Article 84 would directly apply by virtue of that form, even if the levy also serves as a quid pro quo for benefits. Legal commentary suggests this distinction is based on the idea that choosing the "tax" label deliberately subjects the levy to the constitutional rules governing taxes.

The "Spirit" (趣旨 - shushi) of Article 84

Despite finding Article 84 not directly applicable, the Court did not stop there. It recognized that the underlying legal principle of Article 84 – that imposing obligations or restricting citizens' rights requires a legal basis – has broader significance.

- The Court stated that even public levies other than taxes (公課 - kōka), which are assessed and collected by national or local governments, should be appropriately regulated by law, or by ordinances enacted within the scope of empowering laws, depending on their specific nature. Such levies are not automatically outside the ambit of the legal principles embodied in Article 84 simply because they are not formally defined as "taxes".

- Specifically, for public levies that share tax-like characteristics, particularly in the degree of compulsion in their assessment and collection, the spirit (or purport) of Article 84 should be considered to apply.

Degree of Clarity Required for Ordinances Setting Premiums

Given that NHI premiums involve compulsory enrollment and collection, thus resembling taxes in their coercive aspect, the Court affirmed that the spirit of Article 84 indeed applies to them. However, this does not mean the requirements are identical to those for taxes.

- The Court clarified that the degree of specificity and clarity required in an ordinance for setting assessment criteria for NHI premiums (as mandated by Article 81 of the National Health Insurance Act, which requires such matters to be set by ordinance according to standards specified by cabinet order) must be judged comprehensively. This judgment should take into account:

- The nature of the specific public levy.

- The purpose of its assessment and collection.

- The degree of compulsion involved.

- The unique objectives and characteristics of NHI as a social insurance system.

- A key distinguishing factor for NHI premiums is that their use is strictly limited to covering the expenses of the NHI program. This inherent earmarking acts as a safeguard against arbitrary increases for unrelated governmental purposes.

Assessing Asahikawa's Ordinance

Applying these principles, the Supreme Court found that the Asahikawa City NHI Ordinance was not unconstitutional:

- The Ordinance did provide a clear framework and standards for calculating the "total assessable amount" (賦課総額 - fuka sōgaku). This total amount, representing the sum to be collected via premiums, was to be determined based on the estimated necessary expenses for the NHI program in a given fiscal year, minus estimated revenues from sources other than premiums (e.g., government subsidies).

- The Ordinance delegated to the Mayor the task of making specific estimations related to these components – such as projected healthcare costs, other revenues, and the anticipated premium collection rate. The Court found this delegation of authority for technical and specialized estimations to be a matter of the Mayor's rational choice and permissible within the established framework.

- Crucially, these mayoral estimations and the resulting NHI special account budget and financial statements are subject to democratic control by the city council through its deliberation and approval processes. This provides an essential layer of oversight.

- Once the total assessable amount is determined based on the Ordinance's criteria and the Mayor's estimations, the actual premium rates for different categories of insured households are derived more or less mechanically according to formulas also set in the Ordinance. The Court found that this structure leaves no room for arbitrary or politically motivated rate-setting by the Mayor outside the established framework.

- The Court also addressed the concern that premium rates were announced by public notice after the official assessment date (the beginning of the fiscal year). It concluded that this practice did not harm legal stability or violate the spirit of Article 84, because the underlying calculation standards were already clearly laid out in the Ordinance before the fiscal year began, ensuring predictability.

Therefore, the Supreme Court held that the Asahikawa Ordinance's method of determining NHI premium rates did not violate Article 81 of the National Health Insurance Act, nor did it contravene the spirit of Article 84 of the Constitution.

Plaintiff X's appeal was dismissed.

A supplementary opinion by one Justice concurred with the Grand Bench's conclusion. It further emphasized the quid pro quo nature of NHI premiums as payment for essential medical services within a risk-pooling system. While acknowledging that the Mayor's estimation process involves some discretion, the Justice found the system acceptable due to the inherent link between premiums and insurance costs, the limitations on how funds can be used, and the democratic control exercised by the city council over budgets and accounts. This, the supplementary opinion suggested, is permissible from the perspective of insurer (municipal) autonomy in managing the social insurance scheme.

Analysis and Implications

The Asahikawa City NHI premium case is a landmark decision with several important implications:

- Pragmatic Constitutional Interpretation: The ruling reflects a pragmatic approach by the Supreme Court, balancing the fundamental constitutional principle of democratic control over financial burdens (the spirit of Article 84) with the practical necessities of allowing local governments flexibility in administering complex and dynamic social insurance programs like NHI, where costs and revenue needs can fluctuate annually.

- Distinction Between "Direct Application" and "Spirit Application": The Court clearly distinguished between the direct application of Article 84 (which is reserved for formal "taxes") and the application of its spirit or purport to other compulsory public levies like NHI premiums. This nuanced approach allows for differing degrees of legislative specificity depending on the nature of the levy.

- Emphasis on Earmarking and Democratic Oversight: The judgment heavily relied on two key safeguards:

- The fact that NHI premiums are earmarked specifically for NHI program expenses, preventing their diversion to general city revenue.

- The existence of democratic oversight mechanisms, primarily through the city council's role in scrutinizing and approving the NHI special account budget and financial statements. These were seen as crucial checks on the delegated authority.

- Guidance for Other Public Levies: The decision provides a constitutional framework for evaluating other compulsory non-tax public levies in Japan. The required level of detail in the primary law or ordinance can vary based on factors like the levy's purpose, its degree of compulsion, and the presence of other control mechanisms.

- The "Quid Pro Quo" Element: The Court's emphasis on the "quid pro quo" nature of NHI premiums was central to its reasoning for not applying Article 84 directly. While academic debate exists on the true strength of this quid pro quo link, especially given large public subsidies and specific rules on benefit suspension for non-payment, the Supreme Court found the "connection" (kenrensei) between premiums and benefit eligibility to be sufficiently robust for its legal analysis.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's 2006 decision in the Asahikawa National Health Insurance premium case provides a nuanced interpretation of Article 84 of the Japanese Constitution. It clarifies that while NHI premiums are not "taxes" in the strict constitutional sense, their compulsory nature brings them under the "spirit" of Article 84. This means their imposition must be grounded in clear standards set forth in local ordinances, which themselves must be authorized by national law, and must be subject to democratic oversight.

The ruling largely affirmed the prevailing practices for setting NHI premium rates in Japan, thereby providing legal certainty for municipalities. At the same time, it underscored the enduring importance of transparency, clear legal frameworks, and democratic accountability whenever public financial burdens are imposed on citizens, regardless of whether those burdens are labeled "taxes" or "premiums."