Nagoya's Design Expo: A Supreme Court Case on Mayoral Conflicts, Contracts, and Public Funds

Judgment Date: July 13, 2004

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

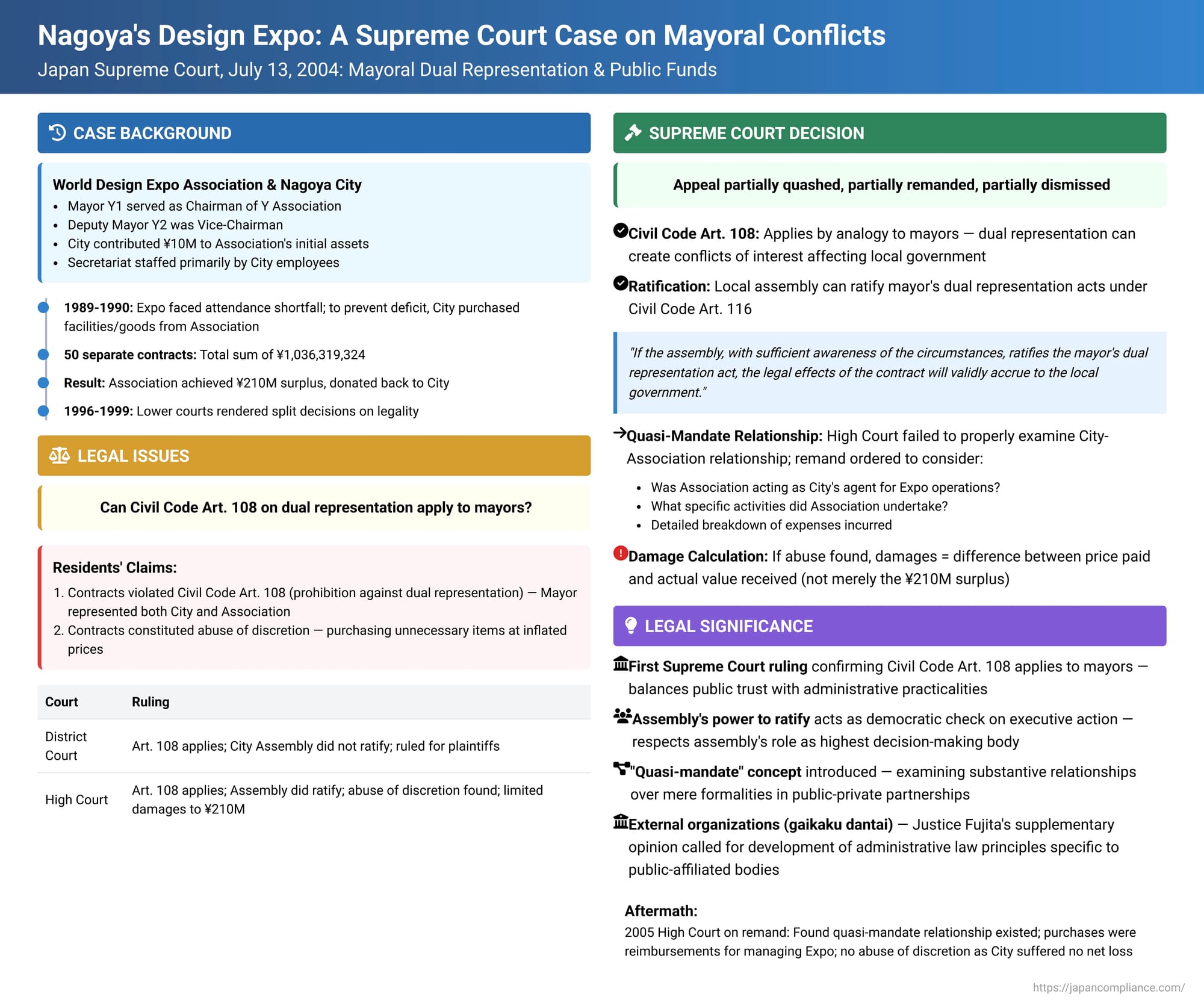

When a city mayor also heads an external foundation set up to run a major city event, and that foundation enters into contracts with the city, complex legal questions arise. A 2004 Japanese Supreme Court decision involving Nagoya City's World Design Exposition delved into such a scenario, addressing the applicability of private law rules on dual representation to public officials, the role of the city assembly in ratifying such acts, and the assessment of whether these contracts constituted an abuse of discretion.

The World Design Exposition: Ambition Meets Financial Reality

In the late 1980s, Nagoya City ("the City") embarked on an ambitious project to commemorate its centennial: the World Design Exposition ("Design Expo"). To manage this event, the City, with cooperation from Aichi Prefecture and various business organizations, established a foundational juridical person, the World Design Exposition Association ("Y Association" or "the Association").

The City's involvement with Y Association was substantial from the outset:

- The City contributed 10 million yen of the Y Association's initial 22.5 million yen in basic assets.

- The City's then-Mayor, Y1, was appointed as Chairman (a director) of Y Association.

- The City's Deputy Mayor, Y2, served as a Vice-Chairman (director).

- The City's Treasurer, Y3, acted as an auditor for the Association.

- The Association's secretariat was primarily composed of City employees.

- Under Y Association's articles of incorporation, Chairman Y1 was authorized to represent the Association, with important operational decisions made by its board of directors.

As the Design Expo progressed, a critical problem emerged: attendance figures were falling short of initial projections. It became evident that revenue from ticket sales and other sources would be insufficient to cover the operational costs. To prevent Y Association from incurring a deficit, the City and Y Association devised a plan: after the Expo concluded, various facilities and goods used during the event—such as buildings, outdoor lighting, benches, and trash receptacles—would be sold or repurposed. The initial contributors to Y Association's basic assets were asked to purchase these items, but only the City agreed to do so.

Consequently, between November 1989 and February 1990, the City and Y Association entered into 50 separate contracts (collectively, "the Contracts"). Through these Contracts, the City purchased the aforementioned facilities and goods from Y Association for a total sum of 1,036,319,324 yen. This financial arrangement resulted in Y Association achieving a surplus of 210 million yen. In March 1990, Y Association's board of directors resolved to donate this entire surplus to the City. Following this, the Association was dissolved.

The Residents' Lawsuit: Allegations of Illegality

A group of Nagoya City residents, X et al., ("the Plaintiffs"), initiated a residents' lawsuit. Such lawsuits are a feature of Japanese local governance, allowing citizens to challenge allegedly illegal financial actions by their local government. The Plaintiffs filed their suit under the then-applicable Article 242-2, Paragraph 1, Item 4 of the Local Autonomy Act.

Their core allegations were:

- The Contracts violated the pre-2017 amendment version of Article 108 of the Japanese Civil Code, which prohibits an agent from acting for both parties in a transaction (dual representation or self-dealing), thereby rendering the contracts invalid. This was based on Mayor Y1 effectively representing both the City (as Mayor) and Y Association (as its Chairman) in these transactions.

- The conclusion of these Contracts constituted an abuse of discretion by the City officials involved, as they allegedly involved purchasing unnecessary items at inflated prices.

The Plaintiffs sought, on behalf of the City, damages from Mayor Y1, Deputy Mayor Y2, and Treasurer Y3. They also sought damages or, alternatively, the restitution of unjust enrichment from Y Association.

The Legal Battles in Lower Courts

First Instance Court (Nagoya District Court):

The District Court, in its judgment on December 25, 1996, found that Civil Code Article 108 did apply by analogy to the situation. It further held that resolutions passed by the City Assembly did not amount to a valid ratification of these dual representation acts under Civil Code Article 116 (which allows a principal to ratify an unauthorized agent's act). Consequently, the court largely ruled in favor of the Plaintiffs. The defendants, including Y1 and Y Association, appealed this decision.

Appellate Court (Nagoya High Court):

The Nagoya High Court, on December 27, 1999, agreed with the District Court that Civil Code Article 108 applied by analogy. However, diverging from the lower court, the High Court found that the City Assembly had validly ratified the Contracts, thereby curing the defect of dual representation and rendering the Contracts effective.

Despite upholding the Contracts' validity, the High Court then examined the claim of abuse of discretion. It concluded that the City's decision to enter into most of the Contracts (with some exceptions) did indeed constitute an abuse of discretion. As a result, the High Court ordered Mayor Y1 and Y Association to pay damages to the City, but limited this liability to 210 million yen—the amount of the surplus Y Association had ultimately donated back to the City. Other claims were dismissed.

Unsatisfied with this outcome, both the Plaintiffs (X et al.) and the defendants (Y1 and Y Association) sought permission to appeal to the Supreme Court, which was granted.

The Supreme Court's Intervention: Key Rulings

The Supreme Court's judgment on July 13, 2004, brought further complexity, involving partial quashing of the High Court decision, partial remand for further proceedings, a partial decision made by the Supreme Court itself, and partial dismissal of appeals. The core legal pronouncements were as follows:

1. Dual Representation (Civil Code Art. 108): Applicable to Mayors

The Supreme Court affirmed that the principle prohibiting dual representation, enshrined in Civil Code Article 108, can be applied by analogy to contracts concluded by the head of a local public entity (like a mayor). The rationale is that if a mayor represents the local government while simultaneously representing or acting as an agent for the other contracting party, there is a potential for the local government's interests to be compromised, much like in private transactions involving dual agency.

2. Ratification by Assembly (Civil Code Art. 116): Possible and Recognized

The Court further held that if a mayor engages in an act of dual representation, Civil Code Article 116, which allows a principal to ratify acts of unauthorized agency, also applies by analogy. Crucially, the Supreme Court recognized that the local assembly (in this case, the Nagoya City Assembly) could act as the ratifying body for the local government (the principal). If the assembly, with sufficient awareness of the circumstances, ratifies the mayor's dual representation act, the legal effects of the contract will validly accrue to the local government.

In the specific facts of this case, the Supreme Court found that the Nagoya City Assembly had indeed ratified the Contracts. The Court noted that the Assembly was fully aware that Mayor Y1 was also the Chairman of Y Association when these Contracts were made. The Assembly had deliberated on these Contracts and related budgetary matters in special committees and plenary sessions and had passed relevant resolutions. This was deemed sufficient to constitute ratification, thereby curing the initial procedural defect arising from dual representation.

3. Assessing Abuse of Discretion: The "Quasi-Mandate" Factor and Remand

While ratification addressed the dual representation issue, it did not resolve the separate question of whether the decision to enter into the Contracts constituted an abuse of discretion. The Supreme Court found the High Court's handling of this issue to be insufficient.

The Supreme Court reasoned that the Design Expo was fundamentally a City project. It was plausible to view the City as having entrusted Y Association with the concrete preparations and operational management of the Expo, based on the City's overall plan. This suggested the existence of a "quasi-mandate" (jun-inin) relationship between the City and Y Association. A quasi-mandate is a legal concept where one party entrusts another with the management of affairs that are not strictly legal acts but involve factual conduct.

If such a quasi-mandate relationship existed, the Supreme Court posited, then it might not be unreasonable for the City to compensate Y Association for necessary expenses incurred in fulfilling its entrusted duties, especially if those expenses could not be covered by Y Association's basic assets and revenue from the Expo. There might even be a legal obligation on the City to provide such compensation.

This potential quasi-mandate relationship, and the associated possibility of a City obligation to cover Y Association's legitimate deficits, was deemed a "crucial consideration" in determining whether the City's decision to purchase the assets (effectively covering Y Association's shortfall) amounted to an abuse of discretion.

The Supreme Court concluded that the High Court had erred by ruling on the abuse of discretion claim without adequately examining:

- The substantive nature of the relationship between the City and Y Association concerning the Expo's preparation and operation.

- The specific details of the activities undertaken by Y Association.

- A thorough breakdown of the expenses incurred by Y Association.

Because the High Court's judgment on abuse of discretion was made without establishing these critical facts, the Supreme Court found this part of the judgment to be flawed by a violation of law that clearly affected its outcome. Consequently, this aspect of the case was remanded to the Nagoya High Court for further examination.

The Supreme Court also commented on the calculation of damages. It stated that if an abuse of discretion were found, the damages incurred by the City should be the difference between the price paid for the assets and the actual value of those assets acquired by the City. The High Court’s approach of limiting damages to the 210 million yen surplus, based on the likelihood that the City would have had to provide a subsidy anyway, was criticized. The Supreme Court noted that subsidies require specific public interest justifications and assembly approval, and mere probability of subsidy provision is not a proper basis for damage calculation. The objective value of the acquired property had to be factored in.

Deeper Dive: Legal Principles and Debates

This case touches upon several important legal principles and ongoing debates in Japanese administrative and civil law.

The Mayor as a "Dual Agent": Balancing Public Trust and Practicalities

This was the first Supreme Court decision to explicitly affirm the analogous application of Civil Code Article 108 (prohibiting dual representation) to contracts entered into by the head of a local government. This aligns with the general legal doctrine in Japan that private law provisions apply to the private law acts of public bodies unless specifically excluded by public law. Article 108 aims to protect the principal's interests by preventing conflicts of interest. While the Supreme Court in this case didn't delve into whether a concrete conflict of interest had materialized, it proceeded on the basis that the potential for such a conflict was sufficient to trigger the rule.

The Assembly's Power to Ratify: A Check on Executive Action

The question of whether a local assembly can ratify a mayor's act of dual representation was contentious. Prior to this ruling, some administrative practices and lower court opinions (including the first instance court in this case) denied such a power, often based on the separation of powers between the legislative assembly and the executive (the mayor). The Nagoya High Court, however, had analogized to company law (where a board can ratify acts) and affirmed the assembly's power, given its role as the residents' representative body and the highest decision-making organ of the local government. The Supreme Court concurred with the High Court's conclusion on this point, though it did not explicitly detail the legal basis for the assembly's ratification authority. Legal scholars have noted that if the assembly could not ratify, then no internal organ of the local government could, potentially leaving such acts incurably void. The assembly's deliberative and approval processes can serve as the necessary check on the mayor's actions in such situations. The degree of awareness the assembly must have for ratification to be effective is another point of discussion, with the Supreme Court seemingly inferring sufficient awareness from the fact that deliberations and resolutions concerning the contracts took place.

Beyond Formalities: The Substance of the City-Association Relationship

The Supreme Court's decision to remand the case for a deeper look at the "quasi-mandate" relationship highlights a preference for examining the substantive realities over mere formalities. If Y Association was essentially acting as the City's arm for managing the Expo, and the City had an obligation to cover legitimate costs, then purchasing assets to clear a deficit might be justifiable, rather than an abuse of discretion. However, the commentary notes this was just one factor. Other procedural questions, such as whether these purchases were effectively subsidies that bypassed proper public interest assessments (required by Local Autonomy Act Art. 232-2) or whether using multiple smaller contracts was a way to circumvent assembly approval thresholds for large acquisitions, remained as potential points of illegality.

The Challenge of "External Organizations" (Gaikaku Dantai)

Justice Hiroyasu Fujita, in a supplementary opinion to the main judgment, raised a significant point about the broader legal framework for "gaikaku dantai" – external organizations that, while having separate legal personalities, maintain close organizational and financial ties with administrative bodies like local governments. He noted that Y Association, being legally distinct from the City yet operationally intertwined and led by City officials, exemplified such an entity. Justice Fujita questioned whether uniformly applying private law concepts like dual representation (Civil Code Art. 108) is always appropriate for the diverse range of relationships between public bodies and their gaikaku dantai. He suggested that while no special administrative law principles for maintaining an "appropriate distance" and managing conflicts of interest in these specific contexts were yet established (making the application of Art. 108 currently unavoidable), the future development of such tailored administrative law doctrines might be desirable. This case, therefore, also flags the need for clearer legal rules governing the relationship between administrative entities and their affiliated organizations, and how these "external organizations" should be positioned within administrative organization law.

The Aftermath: The Remand Decision

Following the Supreme Court's remand, the Nagoya High Court reconsidered the abuse of discretion issue. In its subsequent decision on October 26, 2005, the High Court found that a quasi-mandate relationship did exist between the City and Y Association. It concluded that the payments made by the City under the Contracts were essentially reimbursements for expenses incurred by Y Association in managing the Expo. Furthermore, given that Y Association had donated its entire surplus (which arose from these payments) back to the City, the High Court determined that there was no abuse of discretion in the City's conclusion of the Contracts. The rationale appears to be that since the primary aim of this type of residents' lawsuit is to recover financial losses suffered by the local government, and the City ultimately incurred no net loss, it would be difficult to uphold the claim even if some procedural irregularities existed.

Conclusion: Navigating Public-Private Complexities

The 2004 Supreme Court decision in the Nagoya World Design Exposition case provides important, albeit complex, guidance on several fronts. It confirms that fundamental private law principles like the prohibition of dual representation extend to public officials acting on behalf of local governments, but also recognizes the power of local assemblies to ratify such actions, thereby providing a mechanism for validating potentially flawed contracts. Perhaps most significantly, the case underscores the judiciary's willingness to look beyond formal structures to the substantive nature of relationships between local governments and their closely affiliated "external organizations." By remanding the case for a detailed examination of the potential "quasi-mandate" relationship, the Court emphasized that assessing the legality of financial transactions in such public-private partnerships requires a thorough understanding of the mutual obligations and the ultimate financial impact on the public entity. Justice Fujita's supplementary opinion further highlights the ongoing need to develop more nuanced administrative law principles to govern the increasingly common use of such external bodies in public service delivery and project management.