My Agent, My Benefit, My Right to Terminate? Japanese Supreme Court on Agency Contracts for Mutual Interest

Date of Judgment: January 19, 1981

Case Name: Claim for Assigned Debt

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

Introduction

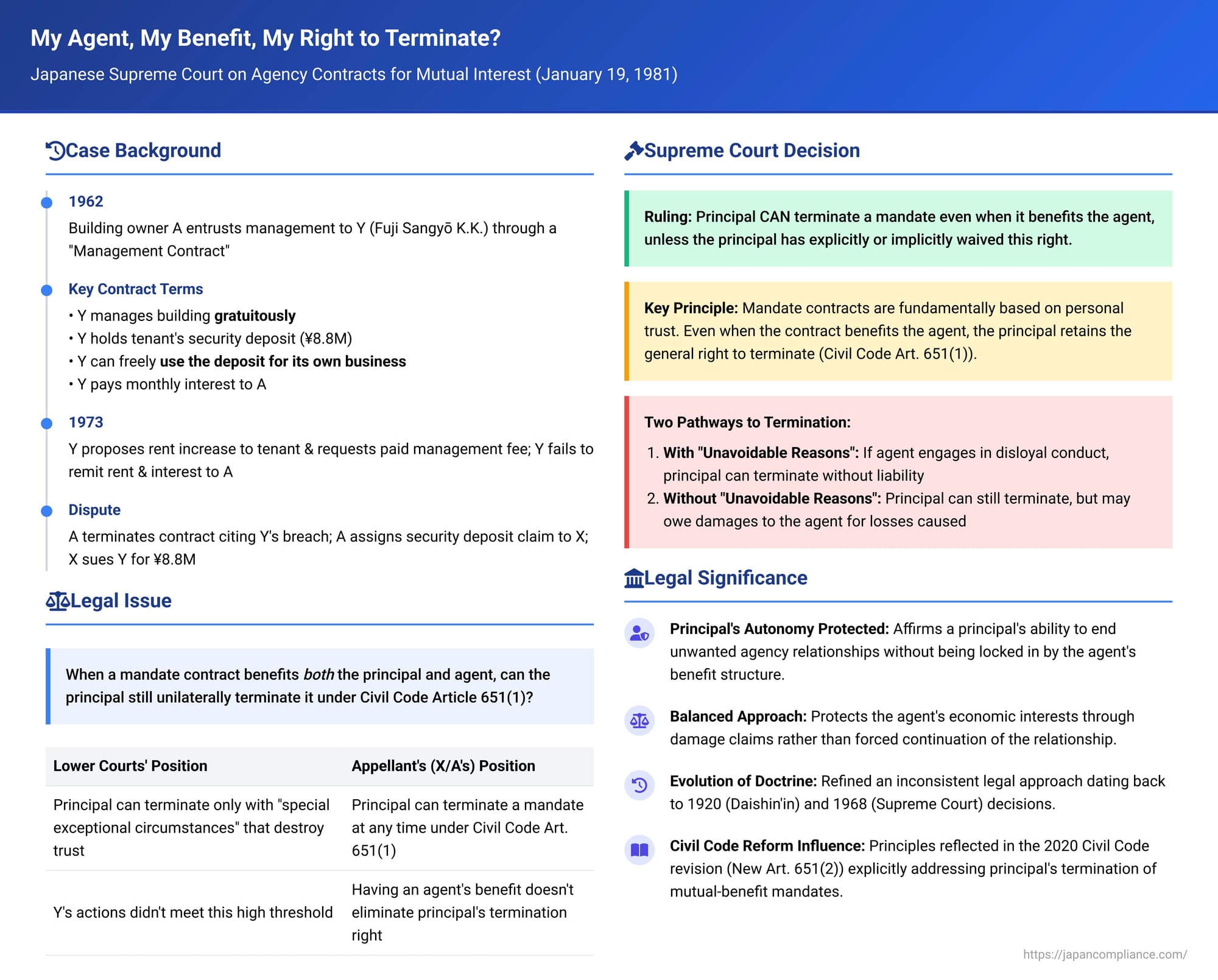

Agency or mandate contracts (委任契約 - inin keiyaku) are foundational to many business and personal dealings in Japan. Rooted in trust between the principal (who entrusts a task) and the agent (who undertakes it), these contracts traditionally allowed either party to terminate the relationship relatively freely. But what happens when the agency arrangement is structured not just to benefit the principal, but also to provide a significant, independent benefit to the agent? Can the principal still terminate the contract at will, potentially jeopardizing the agent's interest? A key Japanese Supreme Court decision from January 19, 1981, addressed this complex interplay.

A Building Management Deal with a Twist: The Factual Background

The case involved a long-term building management agreement with an unusual feature benefiting the agent:

- The Parties and the Initial Setup:

- A: The owner of a building who, in 1962, leased it out to a tenant, Company B.

- Y (Fuji Sangyō K.K.): An architectural and real estate management company that had been involved in the building's original construction. A entrusted Y with the ongoing management of the building and the collection of rent from Company B. This was formalized in a "Management Contract."

- Terms of the Management Contract:

- Y was responsible for collecting rent and remitting it to A.

- Y would also handle the payment of property taxes and arrange for building repairs, with A bearing the actual costs.

- Y was entrusted with holding the substantial security deposit paid by the tenant (Company B) to A. Y was to pay A monthly interest on this deposit.

- The contract had an initial term of five years, with provisions for successive renewals.

- A crucial aspect was that Y's building management services were to be provided gratuitously (無償 - mushō) – Y would not charge A a fee for these services.

- The Agent's Benefit: In exchange for, or in conjunction with, the gratuitous management, A granted Y permission to freely use the tenant's security deposit (¥8.8 million) for Y's own business operations. Y actively utilized these funds for its business for many years.

- Deterioration of the Relationship: By 1973, the relationship began to sour. Y proposed a rent increase to the tenant, Company B. Around the same time, Y also requested A to convert the (hitherto gratuitous) building management into a paid service. Subsequently, Y failed to remit two months' worth of collected rent to A and also stopped paying A the agreed-upon monthly interest on the security deposit that Y was holding and using.

- Termination and Lawsuit:

- In response to Y's actions, A declared the immediate termination of the Management Contract, citing Y's default (breach of contractual obligations).

- A also notified Y that A had assigned their claim for the return of the security deposit (still held by Y) to X.

- X then sued Y to recover the ¥8.8 million security deposit, plus late payment interest.

- Lower Court Rulings: Both the first instance court and the High Court dismissed X's claim (and thus, indirectly, A's termination). Their reasoning was that because the Management Contract provided a significant benefit to Y (the free use of the security deposit), A (the principal) could not unilaterally terminate it unless there were "special exceptional circumstances" that made continuation of the contract untenable, such as a fundamental destruction of the trust relationship due to a severe breach by Y. The lower courts found that Y's actions did not meet this high threshold, meaning the contract was, in their view, still in force and the security deposit not yet repayable in the manner claimed.

X appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing primarily that a building management agreement is a form of quasi-mandate, and under the then-existing Civil Code Article 651, Paragraph 1, a principal (A) had the right to terminate such a contract at any time.

The Supreme Court's Reversal

The Supreme Court, in its judgment on January 19, 1981, overturned the High Court's decision and remanded the case for further proceedings. The Supreme Court provided a nuanced interpretation of the principal's right to terminate a mandate contract that also serves the agent's interests.

Core Rulings of the Supreme Court:

- Nature of the Contract: The Court affirmed that the Management Contract between A and Y fell within the legal category of a mandate agreement (or an agreement akin to it).

- Termination of Mandates Also Benefiting the Agent: The Court then addressed the central issue:

- Termination for "Unavoidable Reasons": It is a matter of course that even in a mandate entered into for the benefit of both the principal and the agent, the principal can terminate the contract if "unavoidable reasons" (やむを得ない事由 - yamu o enai jiyū) exist. Such reasons would include situations where the agent engages in significantly disloyal or untrustworthy conduct (the Court cited its own prior judgments from 1965 and 1968 on this point).

- Termination Without "Unavoidable Reasons": More significantly, the Supreme Court held that even if such unavoidable reasons are absent, the principal can still terminate the mandate contract in accordance with (the then-existing) Civil Code Article 651, provided there are no circumstances indicating that the principal has effectively waived their inherent right to terminate.

- Rationale: The Court reasoned that mandate contracts are fundamentally based on the personal trust relationship between the parties. To compel a principal to continue a mandate relationship against their will, solely because the arrangement also happens to benefit the agent, could ultimately harm the principal's own interests and would contradict the core purpose of a mandate (which is to have tasks performed according to the principal's wishes and in their interest).

- Protecting the Agent's Interest: If the agent suffers a loss as a direct result of such a termination by the principal (and the termination is not due to the agent's own fault or other "unavoidable reasons" justifying termination without compensation), the agent's interest is sufficiently protected by their right to claim compensation for damages from the principal.

- Error of the Lower Courts: The High Court had erred by assuming that A could only terminate the Management Contract if "unavoidable reasons" existed. It failed to examine the distinct question of whether A, by the terms of the contract or by subsequent conduct, had waived the general right of termination afforded to principals under Civil Code Article 651.

The case was remanded for the High Court to make this determination. (As a factual postscript, the commentary provided with the case notes that on remand, the Tokyo High Court found that A had not waived the termination right, that A's termination was therefore valid, and consequently ruled in full favor of X's claim for the return of the security deposit).

Unpacking the Rules of Mandate Termination in Japan

This 1981 Supreme Court decision was a significant step in clarifying the law surrounding the termination of mandate contracts, especially those with a dual-benefit aspect.

Former Civil Code Article 651: The Starting Point

Under the Japanese Civil Code as it existed at the time of this ruling (prior to major reforms in 2017/2020), Article 651 stated:

- Paragraph 1: A mandate could be terminated by either party (principal or agent) at any time.

- Paragraph 2: If a party terminated the mandate at a time that was "unfavorable" to the other party, the terminating party was liable for any damages caused, unless the termination was due to an "unavoidable reason."

This provision strongly emphasized the personal and trust-based nature of mandate agreements, allowing for relatively easy exit, albeit with potential financial consequences.

The Complication of the "Agent's Interest"

The straightforward application of Article 651(1) became complicated when the mandate was structured to benefit the agent as well as the principal.

- Early Case Law (e.g., Daishin'in 1920): An early Supreme Court (then Daishin'in) decision had held that if a mandate also served the agent's interest, the principal could not freely terminate it under Article 651(1). This created a potential trap for principals: what if they lost confidence in the agent but were locked into the relationship because of the agent's vested interest?

- Later Clarification (e.g., Supreme Court 1968): A subsequent Supreme Court case clarified that even in such "mutual benefit" mandates, the principal could terminate if "unavoidable reasons" existed, such as serious misconduct or breach of trust by the agent.

The 1981 Judgment's Key Contribution

The 1981 Supreme Court judgment (the subject of this post) further refined this doctrine:

- It established that the principal's ability to terminate was not solely limited to situations involving "unavoidable reasons" attributable to the agent.

- The principal retained their general right to terminate under Article 651(1) unless they had waived this right (either expressly or implicitly).

- The agent's interest in the continuation of the mandate was primarily to be protected through a claim for damages against the principal if the termination (without fault on the agent's part) caused them loss, rather than by forcing the continuation of an unwanted agency relationship.

This created a framework where a principal could generally terminate even a mutually beneficial mandate, but the assessment would involve checking for (a) "unavoidable reasons" (if present, termination is clear, possibly without liability for damages by the principal) or (b) absence of waiver of the termination right (if no unavoidable reasons, termination is still possible, but principal may owe damages to the agent).

Impact of the 2017/2020 Civil Code Reforms on Article 651

The rules regarding mandate termination in Article 651 were revisited during the major Civil Code reforms.

- New Article 651, Paragraph 1 maintains the principle that either party may terminate a mandate at any time.

- New Article 651, Paragraph 2 still deals with damages. It now specifies two situations where the terminating party must compensate for the other party's damages (unless there was an "unavoidable reason"):

- If they terminate the mandate at a time unfavorable to the other party.

- (New specific provision) If the principal terminates a mandate that was also for the agent's benefit (explicitly excluding benefits derived solely from receiving remuneration).

This explicit inclusion in Paragraph 2(ro) concerning mandates for the agent's benefit is significant. It codifies and arguably clarifies the protection for the agent. The primary right of the principal to terminate (under Paragraph 1) is robustly maintained. If the mandate also served the agent's distinct interest (beyond just earning fees), and the principal terminates without an "unavoidable reason," the agent now has a clearer statutory basis for claiming damages.

The practical effect might be that the somewhat complex judicial analysis of whether a principal had "waived" their termination right (as highlighted in the 1981 judgment) may become less central for this specific type of termination, as the statute now directly links the termination of such a mandate to potential compensation for the agent. However, the concept of "unavoidable reason" remains critical, as its presence can absolve the terminating principal from liability for damages. Past judicial interpretations of what constitutes "unavoidable reasons" (e.g., acts by the agent that betray trust, fundamental disagreements on how to conduct the mandated affairs, or an agent's refusal to follow lawful instructions) will likely continue to be relevant.

Conclusion

The 1981 Supreme Court decision, further shaped by subsequent Civil Code reforms, confirms a principal's broad authority to terminate an agency or mandate agreement in Japan. Even if the arrangement was designed to also benefit the agent, the principal generally retains the power to end the relationship. This underscores the primacy of the principal's autonomy in directing their affairs. However, this power is not without consequence. The agent's legitimate interest in the continuation of such a mutually beneficial mandate is now primarily protected through a statutory right to claim damages from the principal if the termination occurs without "unavoidable cause" attributable to the agent. This legal framework seeks to balance the principal's need for control and flexibility with the need for fairness to agents who may have relied on the continuation of the agency for their own benefit.