Municipal Waste, Mayoral Discretion: Japan's Supreme Court on General Waste Collection Permits

A First Petty Bench Ruling from January 15, 2004

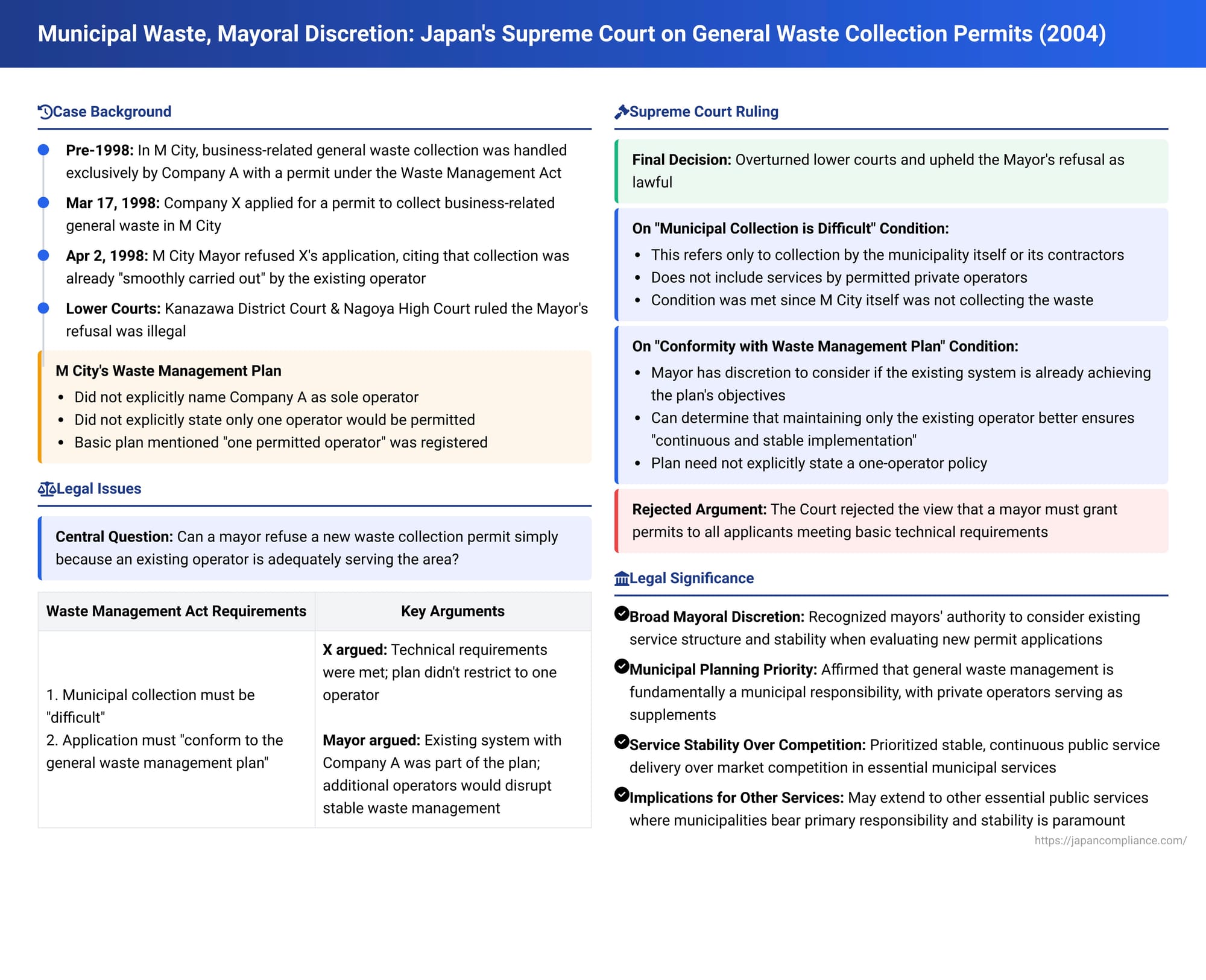

The management of general waste is an essential public service, critical for public health and environmental protection. In Japan, municipalities bear the primary responsibility for this task. However, they can also permit private operators to collect and transport general waste. This raises important legal questions about the scope of a municipality's discretion when deciding whether to grant new permits, especially if an existing operator is already servicing the area. A 2004 Supreme Court of Japan decision by its First Petty Bench (Heisei 14 (Gyo Hi) No. 312) addressed these issues, clarifying the extent to which a city mayor can consider the existing service structure and the city's overall waste management plan in denying a new permit application.

The M City Waste Collection Scenario

The case arose in M City. At the time, the collection and transportation of "business-related general waste" (事業系一般廃棄物 - jigyōkei ippan haikibutsu), which is general waste generated from commercial, industrial, or other business activities, was exclusively handled by a single private company, "Company A". Company A held a permit issued by the Mayor of M City under Article 7, paragraph 1 of the Waste Management and Public Cleansing Act (廃棄物の処理及び清掃に関する法律 - Haikibutsu no Shori oyobi Seisō ni Kansuru Hōritsu, hereinafter "Waste Management Act" or WMA).

M City, as required by Article 6, paragraph 1 of the WMA, had established a General Waste Management Plan (一般廃棄物処理計画 - ippan haikibutsu shori keikaku). This plan consisted of a basic plan and an implementation plan. The basic plan mentioned that one permitted operator was registered for the direct hauling of waste to disposal sites. The implementation plan stated that the collection and transportation of business-related general waste were to be carried out either by the businesses generating the waste themselves or by a permitted operator. Notably, the plan did not explicitly name Company A as the sole operator nor did it state that only one operator would be permitted in the city.

Against this backdrop, X (the plaintiff/appellee), a waste management business operator, applied to Y, the Mayor of M City (the defendant/appellant), on March 17, 1998, for a permit under WMA Article 7, paragraph 1. X sought permission to engage in the business of collecting and transporting business-related general waste (excluding human waste and septic tank sludge) within M City.

The Mayor's Refusal and the Legal Challenge

On April 2, 1998, Mayor Y issued a decision refusing X's permit application (本件不許可処分 - honken fukyoka shobun, "the present non-permission disposition"). The stated reasons for the refusal were: "In M City, the collection and transportation of general waste is being smoothly carried out by the existing permitted operator, and a new permit application does not conform with Article 7, paragraph 3, items 1 and 2 of the Waste Management Act". (Note: These provisions correspond to the current Article 7, paragraph 5, items (i) and (ii) of the WMA).

- The first condition cited (then WMA Art. 7(3)(i), now 7(5)(i)) requires that for a permit to be granted, it must be difficult for the municipality itself to collect or transport the general waste in question.

- The second condition (then WMA Art. 7(3)(ii), now 7(5)(ii)) requires that the permit application conform to the municipality's general waste management plan.

X challenged the Mayor's refusal in court. The Kanazawa District Court (first instance) ruled in favor of X, finding the Mayor's refusal illegal. It reasoned that M City itself was not collecting business-related general waste, so the condition of municipal collection being difficult was indeed met. Furthermore, the court found that the Mayor had misinterpreted M City's waste management plan by assuming it allowed only Company A to operate; since the plan did not explicitly state this, refusing X based on this interpretation was an error. The Nagoya High Court, Kanazawa Branch (second instance), upheld this ruling. The Mayor (Y) then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision of January 15, 2004

The Supreme Court reversed the decisions of the lower courts and upheld the Mayor's refusal to grant X a permit as lawful.

Core Reasoning – Interpreting the Waste Management Act:

- "Municipal Collection is Difficult" (WMA Art. 7(5)(i), then Art. 7(3)(i)):

- The Court first affirmed the principle that municipalities are primarily responsible for managing general waste within their jurisdictions. This responsibility can be fulfilled either by the municipality conducting operations directly or by entrusting (委託 - itaku) these operations to third parties (as stipulated in WMA Articles 4(1), 6, and 6-2).

- The phrase "collection or transportation by the said municipality" within the permit condition refers specifically to waste management activities carried out by the municipality itself or by entities to whom it has formally entrusted these tasks (contractors).

- Crucially, this phrase does not include collection or transportation services provided by private operators who have received an Article 7 permit to conduct such business independently.

- Therefore, the Supreme Court agreed with the lower courts on this point: even if an existing permitted private operator (like Company A) is adequately servicing the area, the condition that "municipal collection is difficult" is still satisfied if the municipality itself (or its direct contractors) would find it difficult to undertake that specific category of waste collection. Since M City was not itself collecting business-related general waste, this condition was met for X's application.

- "Conformity with the General Waste Management Plan" (WMA Art. 7(5)(ii), then Art. 7(3)(ii)):

- This was the pivotal point of the judgment. The WMA mandates that each municipality establish a General Waste Management Plan. This plan must, among other things, include projections of waste generation and disposal volumes, and lay down "basic matters concerning the appropriate disposal of general waste and the persons who are to implement it" (WMA Article 6, paragraph 2, items (i) and (iv)).

- The Supreme Court interpreted this to mean that the plan is intended to designate the primary entities responsible for waste processing based on these projected volumes and needs.

- Flowing from this, the Court reasoned that in situations where existing permitted operators have been effectively and appropriately collecting and transporting general waste, and the municipality's General Waste Management Plan has been formulated taking this established operational reality into account (even if not explicitly naming the operator or stating it's an exclusive arrangement), the mayor possesses the discretion to make a specific judgment when reviewing a new permit application.

- Specifically, the mayor can determine that, in order to ensure the "continuous and stable implementation of appropriate general waste collection and transportation," it is more suitable to have only the existing permitted operator(s) continue these services. In such circumstances, the mayor can legitimately conclude that the new application "is not deemed to conform to the general waste management plan".

Application to M City's Case:

- The Supreme Court found it reasonable to infer that M City's General Waste Management Plan had been created based on the existing situation where Company A was already smoothly and effectively carrying out the collection and transportation of business-related general waste.

- Therefore, the Mayor's stated reason for refusal—that the existing operator was performing well and a new permit would not conform to the WMA requirements—was, in substance, a judgment that it was more appropriate for ensuring continuous and stable waste management to allow Company A alone to continue these services, rather than granting a new permit to X. This effectively meant X's application was deemed not to conform with the operational realities and objectives embedded within (even if not explicitly detailed in the text of) the city's waste management plan.

- The Supreme Court held that such a judgment by the Mayor "cannot be said to be impermissible". Consequently, the Mayor's decision to refuse X's permit application was deemed lawful.

The Nature of General Waste Collection Permits in Japan

This ruling sheds light on the specific nature of permits for general waste collection and transportation under the WMA.

- The WMA establishes general waste management as a primary and fundamental responsibility of municipal governments. They are expected to provide this service directly or through formal entrustment to contractors.

- The Article 7 permit system, which allows private businesses to independently engage in general waste collection and transportation as a business, functions as an exception or supplement to this primary municipal role.

- This statutory structure implies a system where the municipality maintains significant control and planning oversight over general waste management within its jurisdiction. It is not envisioned as an entirely open, free-market system where anyone meeting basic technical criteria is automatically entitled to a permit.

- Therefore, the "permit" (許可 - kyoka) under WMA Article 7 for general waste has a "different nature" from, for example, permits for industrial waste collection and transportation (governed by WMA Article 14), which tend to operate more on a free-competition basis once technical and financial standards are met. The general waste permit system allows for, and indeed seems to anticipate, a degree of municipal supply-demand adjustment (需給調整 - jukyū chōsei) and planning to ensure efficient and stable service delivery for the entire community. The commentary also points to WMA Article 7, paragraph 11 (regarding the designation of business zones) as a provision that implicitly supports the notion of municipal planning and potential limitation of operators within specific areas.

Scope of Mayoral Discretion

The Supreme Court's decision in this case recognized a "considerably broad discretion" for mayors in deciding whether to grant Article 7 permits for general waste management.

- This discretion involves not only assessing an applicant's technical capabilities and financial soundness but also considering whether granting a new permit would ensure the proper and stable provision of waste management services for the entire municipal area, taking into account existing service levels and the objectives of the city's General Waste Management Plan.

- This can include the authority to effectively protect the operational stability of existing, efficient service providers if the mayor reasonably judges this to be necessary for the overall continuity and adequacy of waste management services for the community. The commentary notes that some scholars have raised questions about the appropriateness of allowing the protection of existing businesses to be a factor within this discretion.

- In this specific case, the Court implicitly found that Mayor Y's interpretation of M City's somewhat inexplicit plan—as effectively supporting the continuation of the existing single-operator system provided by Company A—was a permissible exercise of this broad discretion.

Implications for Other Regulated Services

The legal commentary suggests that the reasoning in this Supreme Court judgment might extend to other types of permit systems for essential public services, particularly where the following conditions are met:

- The governing law primarily obligates public bodies (like municipalities) to provide the service, with permits for private operators being an exception or supplement.

- The service in question is vital to public life, requiring stable, continuous, and adequate provision, and there are inherent limits to the overall volume of business (e.g., a limited amount of waste to be collected).

- The public body bears overall legal responsibility for ensuring the proper and effective provision of the service throughout its jurisdiction.

- The public body is required to formulate a comprehensive plan for the service, designating or identifying the entities responsible for its implementation.

- Decisions on granting permits to private operators require an assessment of conformity with this comprehensive service plan.

Conclusion

The 2004 Supreme Court decision in the M City waste collection permit case is a significant ruling that affirms a considerable degree of mayoral discretion in managing general waste collection services. It highlights that, even in the absence of explicit statutory clauses that allow for limiting the number of new entrants to a market, the overarching responsibility of a municipality to ensure stable, planned, and adequate public service delivery can justify a decision to refuse new permits. This is particularly true if the existing system, as reflected in and supported by the municipality's comprehensive management plan, is deemed to be functioning effectively. The judgment underscores a more planned and controlled approach to certain essential local services, prioritizing overall service integrity and stability, rather than a purely market-driven model based solely on an applicant meeting technical qualifications.