Mortgagee's Reach: Can a Japanese Mortgage Extend to Rental Income from the Property?

Date of Judgment: October 27, 1989

Case Name: Claim for Return of Unjust Enrichment

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Second Petty Bench

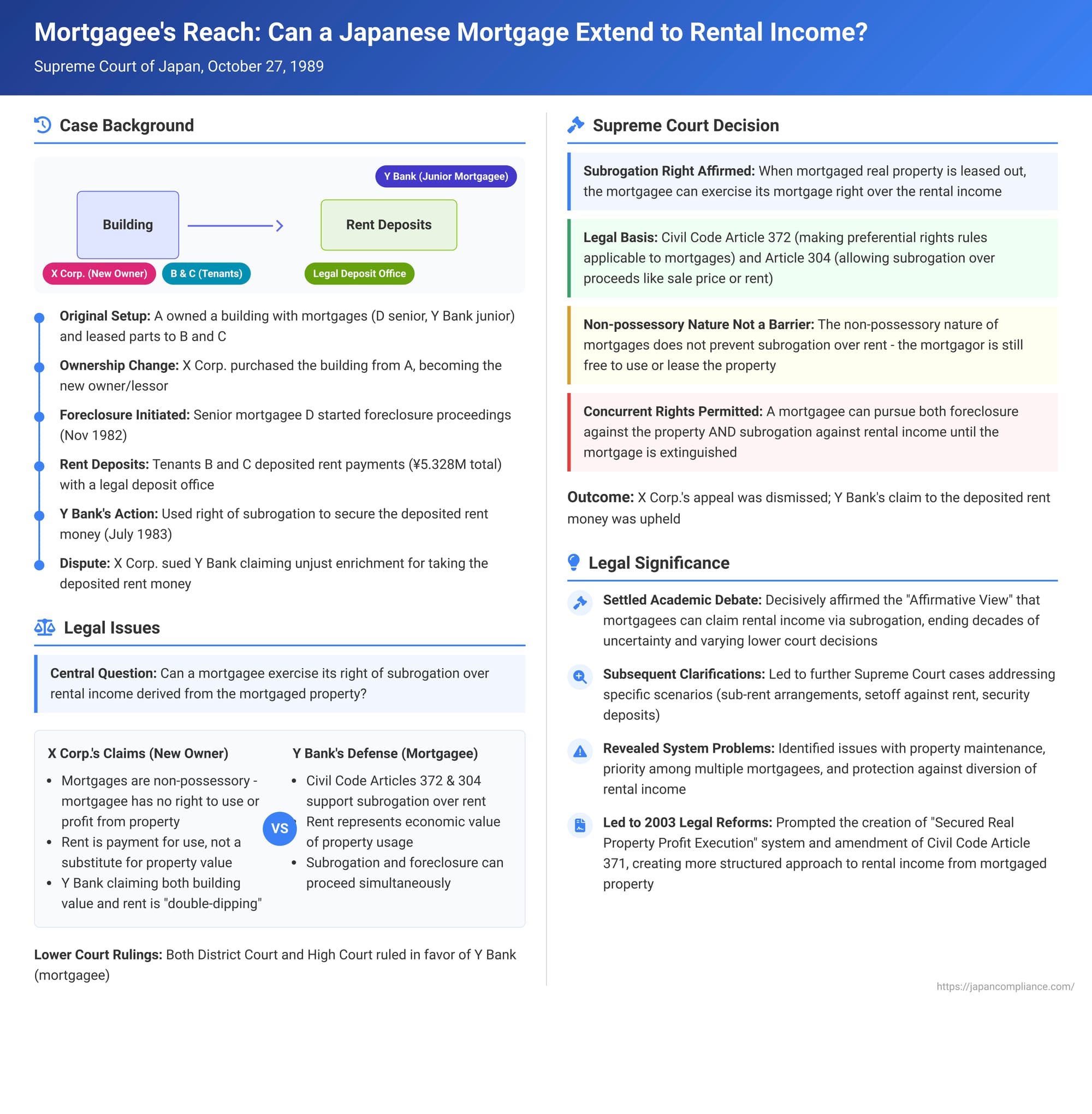

A mortgage is a cornerstone of secured lending, granting the lender (mortgagee) a security interest in the borrower's (mortgagor's) real property. Typically, this security is realized by foreclosing on the property if the debt is not paid. However, what if the mortgaged property is generating income, such as rent from leases? Can the mortgagee also lay claim to this rental income, especially if the proceeds from a foreclosure sale might be insufficient to cover the debt? This question, concerning a mortgagee's right of "subrogation over property" (butsujō daii) to claim rental income, was decisively addressed by the Supreme Court of Japan in a landmark judgment on October 27, 1989.

The Factual Landscape: A Mortgaged Building, Leases, and Foreclosure

The case involved a multi-layered scenario:

- An individual, A, owned a building (the "Building") which was partly leased out. The first floor was leased to B, and the second floor to C.

- The Building was subject to multiple mortgages. A senior mortgage was held by D. Subsequently, a junior root mortgage (neteitōken) was created and registered in favor of Y Bank. (A root mortgage secures a range of unspecified future debts up to a certain maximum amount).

- Later, X Corp. purchased the Building from A, thereby also succeeding to A's position as the lessor to the tenants B and C.

- The senior mortgagee, D, initiated foreclosure proceedings against the Building. On November 30, 1982, a court order commencing the compulsory auction was issued.

- Following the commencement of the auction process, the lessees, B and C, began depositing their rent payments with a legal deposit office (kyōtaku), a common procedure when the entitlement to receive rent becomes uncertain due to creditor actions.

- Y Bank, as the junior root mortgagee, took steps to secure its claim. It participated in the distribution process for the proceeds from the auction of the Building itself (though, at the time of the dispute reaching the Supreme Court, it had not yet actually received its share from these auction proceeds).

- Separately, in July 1983, Y Bank invoked its right of subrogation based on its root mortgage. It targeted the claims for the refund of the rent monies that had been deposited by the lessees: ¥4.05 million deposited by B (for rent accrued from November 1982 to July 1983) and ¥1.278 million deposited by C. Y Bank successfully obtained a court order attaching these rent refund claims and also an assignment order (tempu meirei), which effectively transferred these claims to Y Bank.

- X Corp., as the current owner of the Building and the successor lessor entitled to the rents, challenged Y Bank's actions. X Corp. filed a lawsuit against Y Bank, claiming that Y Bank had been unjustly enriched by the ¥5.328 million it secured from the deposited rents.

X Corp.'s arguments were principally:

- A mortgage is a non-possessory security interest. This means the mortgagee does not have the right to possess or directly use and profit from the mortgaged property (that right remains with the mortgagor/owner). Therefore, a mortgagee should not be able to exercise subrogation over rental income, which is consideration for the use and occupation of the property.

- Even if subrogation over rent were generally permissible, it was improper for Y Bank to both participate in the distribution of the proceeds from the auction sale of the Building's capital value and simultaneously claim the rental income through subrogation. This amounted to "double-dipping."

The District Court and the High Court both dismissed X Corp.'s claim, upholding Y Bank's right to the rental income via subrogation. The lower courts reasoned, among other things, that rent represents a form of the property's exchange value which the mortgage aims to capture, and that denying subrogation over rent would unduly weaken the mortgage, especially if the property itself cannot be readily sold. X Corp. appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Landmark Decision (October 27, 1989)

The Supreme Court dismissed X Corp.'s appeal, thereby affirming the mortgagee's right to exercise subrogation over rental income from mortgaged property.

I. Subrogation over Rental Income is Permissible:

The Court definitively held that when mortgaged real property is leased out, the mortgagee can, in accordance with the spirit of Article 372 and Article 304 of the Civil Code, exercise its mortgage right over the rental income, including claims for the refund of rent deposited by the lessee.

- Rationale: The Court explained that Article 372 of the Civil Code makes the provisions concerning statutory preferential rights applicable mutatis mutandis to mortgages. Article 304, which deals with preferential rights, allows for subrogation over proceeds such as sale price, rent, or compensation for loss or damage.

The Court reasoned that although a mortgage typically leaves possession with the mortgagor, allowing the mortgagor to use the property or lease it to third parties, this non-possessory nature is not fundamentally different from that of some preferential rights. If the mortgagor, by exercising their right to use the property, leases it and thereby obtains consideration (rent), allowing the mortgagee to exercise their security right over this rent does not, in itself, prevent the mortgagor's permitted use of the property. Therefore, there is no compelling reason to deny the mortgagee's right to pursue the rental income by subrogation, especially when such a right is consistent with the literal application of the cited Civil Code provisions. If the rent has been deposited, the mortgage can be exercised over the claim for the refund of this deposit, as it is considered equivalent to the original rent claim.

II. Concurrent Exercise of Foreclosure and Subrogation over Rent:

The Supreme Court also addressed X Corp.'s "double-dipping" argument. It held that even when foreclosure proceedings against the mortgaged real property itself are underway, the mortgagee can still exercise its right of subrogation against rental income (or its substitute, such as deposited rent refund claims) up until the point the mortgage itself is extinguished as a result of the foreclosure process (e.g., through the sale of the property and distribution of proceeds). The Court cited its own precedent (Supreme Court, July 16, 1970, Minshū Vol. 24, No. 7, p. 965), which had permitted a similar concurrent or selective exercise of rights in a case involving subrogation over compensation money for expropriated land.

Thus, the Supreme Court found the lower courts' conclusions to be correct and dismissed X Corp.'s appeal.

Understanding Subrogation (Butsujō Daii) in Mortgage Law

This judgment hinges on the interpretation of subrogation rights for mortgagees:

- Civil Code Article 304: This article, primarily for statutory preferential rights, states that such a right can be exercised against money or other things the debtor is to receive due to the sale, lease, loss, or damage of the object of the preferential right. It also mandates that the right holder must attach these proceeds before they are paid or delivered to the debtor.

- Civil Code Article 372: This article makes the provisions on preferential rights, including Article 304, applicable "mutatis mutandis" (with necessary changes) to mortgages.

Before this 1989 judgment, there was considerable debate and inconsistency in Japanese legal theory and lower court practice regarding whether mortgagees could claim rental income via subrogation:

- Historical Context: The drafters of the Civil Code (notably Dr. Ume Kenjirō) seemed to envision that Article 304 would apply to allow mortgagees to claim rent. However, another provision, the then-Article 371 of the Civil Code, stated that a mortgage's effect extended to the "fruits" of the mortgaged property only after the property had been attached in foreclosure. This led to conflicting interpretations.

- Academic Split:

- One school of thought (the "Affirmative View," supported by scholars like Dr. Wagatsuma Sakae) argued that rent is an economic realization of the property's exchange value, or a value substitute, and that subrogation over rent doesn't fundamentally strip the mortgagor of their right to use the property. This view aligned with a literal reading of Article 304 as applied via Article 372.

- Another school (the "Negative View," supported by scholars like Dr. Kawai Ken) contended that subrogation is an extraordinary remedy for when the primary collateral becomes unavailable. Since leasing doesn't prevent foreclosure on the property itself, subrogation over rent was deemed unnecessary. Furthermore, they argued that allowing a non-possessory mortgagee to claim rent (which is consideration for use and profit) was inconsistent with the nature of the mortgage. This view tended to interpret the old Article 371 as governing statutory fruits like rent, meaning they could only be claimed after foreclosure proceedings began.

- This Judgment's Impact: The 1989 Supreme Court judgment decisively settled this long-standing debate in favor of the Affirmative View, allowing mortgagees to exercise subrogation over rental income, even before default or the commencement of foreclosure proceedings, and concurrently with foreclosure. This brought much-needed uniformity to legal practice.

Impact and Subsequent Developments

The 1989 ruling had a profound impact, significantly strengthening the mortgagee's position by giving them access to the income stream from mortgaged property. However, this broad affirmation also led to new questions and highlighted potential problems:

- Derivative Issues: Subsequent Supreme Court cases had to address related issues, such as:

- Whether a mortgagee could exercise subrogation against sub-rent if the mortgagor structured a lease and sublease arrangement to potentially shield rental income (generally denied, unless it was an abuse of rights or a sham transaction: Supreme Court, April 14, 2000).

- Whether a lessee could set off a claim they acquired against the lessor after the mortgage was registered, against their rent obligations, to the detriment of a mortgagee seeking subrogation over that rent (generally not allowed to defeat the mortgagee: Supreme Court, March 13, 2001).

- How security deposits interact with a mortgagee's subrogated claim on rent if the lease terminates (generally, the deposit can be applied to the rent claim secured by the mortgagee's subrogation: Supreme Court, March 28, 2002).

Problems and the 2003 Security and Execution Law Reforms

The unconditional affirmation of subrogation over rent also raised practical concerns:

- Property Management: If mortgagees could claim all rental income, including funds notionally covering management and maintenance costs, there was a risk that property upkeep would suffer, potentially leading to a decline in the property's value and its income-generating capacity.

- Priority Among Multiple Mortgagees: Unlike foreclosure proceeds from the sale of the property itself (which are distributed according to mortgage priority), the subrogation mechanism for rent under Article 304 did not have a clear statutory framework for determining priority among multiple mortgagees claiming the same rental stream.

- Effectiveness Against Obstruction: Measures to counter a mortgagor's attempts to divert rental income were not always sufficient.

To address these and other issues, Japan undertook significant reforms to its security and civil execution laws in 2003.

- "Secured Real Property Profit Execution" (tampo fudōsan shūeki shikkō): A new system was introduced (Civil Execution Act, Article 180 et seq.). This procedure allows a mortgagee (and other specified secured creditors), after the debtor's default, to apply to the court for the appointment of an administrator. This administrator manages the mortgaged property, collects rents and other profits, and distributes them to the secured creditor(s) according to their priority. This system is more structured and provides clearer rules for management and distribution than the direct subrogation over rent claims.

- Coexistence of Systems: The traditional right of subrogation over rent (as affirmed in the 1989 judgment) was not abolished. It now coexists with the new profit execution system. Creditors can choose which method to employ, though there are provisions for coordinating the two if they overlap (e.g., a later profit execution proceeding can absorb an earlier subrogation-based attachment). The new system is generally seen as better equipped to handle complex situations or larger properties, while direct subrogation may remain useful for simpler cases or smaller properties due to its potentially lower cost and speed.

- Amendment to Civil Code Article 371: Concurrently, the old Article 371 of the Civil Code was amended. The new Article 371 clarifies that a mortgage extends to the natural and statutory fruits (which includes rent) of the mortgaged property that arise after the debtor has defaulted on the secured obligation. This amendment provides a clearer substantive law basis for the mortgagee's claim to post-default profits, particularly supporting the new profit execution system. It does not mean mortgagees automatically receive post-default rent without any procedural steps; an execution procedure (either profit execution or subrogation) is still necessary.

Modern Academic Distinction: "Alternative" vs. "Additional" Subrogation

In light of these developments, contemporary legal scholarship in Japan often distinguishes between two types of subrogation:

- "Alternative (or Compensatory) Subrogation": This refers to subrogation over proceeds that represent the value substitute of the original collateral, such as insurance money paid for a destroyed building or compensation for expropriated land. This type of subrogation is seen as essential to preserve the mortgagee's security when the original collateral is lost or transformed, and it is generally understood to be available even before the debtor defaults.

- "Additional (or Derivative) Subrogation": This refers to subrogation over the profits or fruits generated by the mortgaged property while it still exists, with rental income being the prime example. Many scholars now argue that the primary substantive basis for this type of subrogation is the amended Article 371 of the Civil Code, meaning it primarily applies to rents (and other fruits) that accrue after the mortgagor has defaulted on the secured debt. However, there is still some discussion about whether pre-default rents that remain unpaid might still be subject to subrogation based on the broader logic of the 1989 Supreme Court judgment and Article 304.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of October 27, 1989, was a landmark decision that unequivocally affirmed a mortgagee's right to exercise subrogation over rental income derived from mortgaged property in Japan. This ruling significantly empowered mortgagees by giving them access to the income stream of the collateral, not just its capital value upon foreclosure, and allowed this concurrently with foreclosure proceedings. While this strengthened the mortgagee's security, it also exposed certain practical complexities and potential inequities, which spurred significant legislative reforms in 2003 with the introduction of the secured real property profit execution system and the revision of Civil Code Article 371. The 1989 judgment remains a critical reference point for understanding the scope of mortgage rights, though its application to rental income is now often analyzed in the broader context of these subsequent legal developments and evolving academic theories distinguishing different forms of subrogation.