Mortgagee's Claim vs. Lessee's Set-Off: A Japanese Supreme Court Balancing Act

Date of Judgment: March 13, 2001

Case Name: Action for Collection of Attached Claim

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, Third Petty Bench

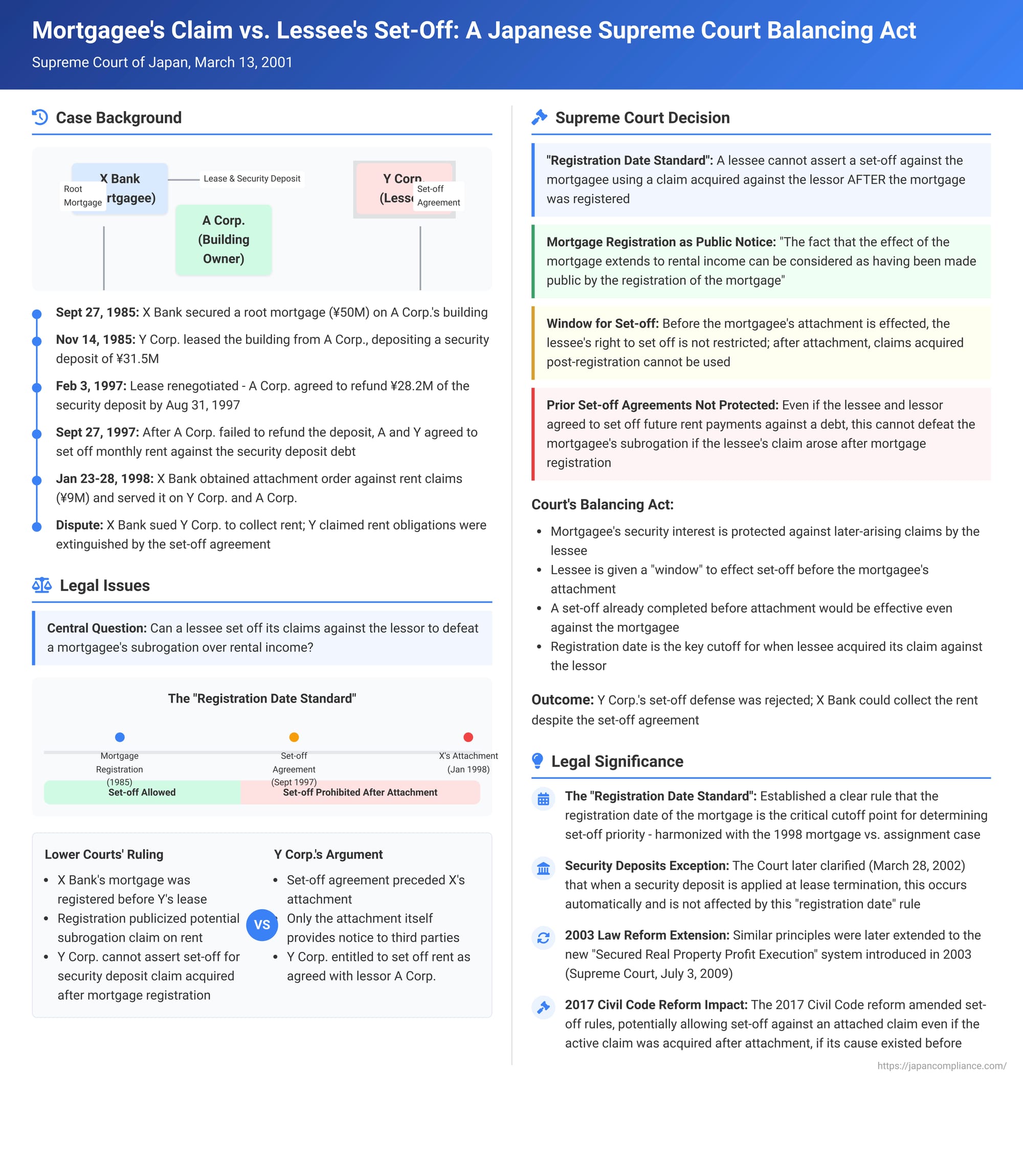

When a property owner mortgages their income-producing real estate, a key question for the lender (mortgagee) is the extent of their security. Beyond foreclosing on the property itself, can the mortgagee also claim the rental income generated by it, especially if the mortgagor defaults? This right, known as "subrogation over property" (butsujō daii), allows a mortgagee to pursue such rental income. However, complications arise when the lessee of the mortgaged property also has a claim against the lessor (the mortgagor) – for instance, a claim for the refund of a security deposit – and wishes to set this off against their rent obligations. A crucial Supreme Court of Japan judgment on March 13, 2001, addressed the priority between the mortgagee's right of subrogation over rent and the lessee's right to effect such a set-off.

The Factual Scenario: A Root Mortgage, a Lease, and a Set-Off Agreement

The case involved a series of transactions and subsequent creditor actions:

- The Mortgage: On September 27, 1985, X Bank secured its claims against A Corp. by obtaining a root mortgage (neteitōken) with a maximum secured amount of ¥50 million over a building ("the Building") owned by A Corp. This root mortgage was registered on the same day.

- The Lease and Security Deposit: On November 14, 1985, Y Corp. entered into a lease agreement with A Corp. to rent the Building. As part of this lease, Y Corp. deposited a substantial security deposit (hoshōkin, also commonly referred to as shikikin) of ¥31.5 million with A Corp.

- Lease Renegotiation and Unrefunded Deposit: On February 3, 1997, A Corp. and Y Corp. agreed to terminate their existing lease agreement effective August 31, 1997, and simultaneously to enter into a new lease for the same Building, commencing September 1, 1997. Under this new arrangement, the security deposit for the new lease was set at a much lower ¥3.3 million. It was agreed that part of the original ¥31.5 million security deposit would be applied to this new, smaller deposit, and A Corp. was to refund the remaining balance of the old deposit, amounting to ¥28.2 million, to Y Corp. by August 31, 1997.

- A Corp.'s Failure to Refund and Set-Off Agreement: A Corp. failed to refund this ¥28.2 million security deposit balance by the agreed date. Consequently, on September 27, 1997, A Corp. and Y Corp. entered into a further agreement to address this outstanding debt. They agreed that:

- The rent (including common service fees) and consumption tax for the Building for September 1997 (totaling ¥346,500) would be immediately set off against A Corp.'s ¥28.2 million security deposit refund obligation.

- For the period from October 1997 through September 2000, the monthly rent and consumption tax (totaling ¥315,000 per month) would be set off against the remaining security deposit refund debt. This set-off for each month's rent was to occur on the last day of the preceding month.

- A Corp. was to pay any final remaining balance of the security deposit refund debt (which was calculated at ¥16,513,500 after accounting for the initial set-offs) by December 31, 1997.

- Mortgagee's Action: Meanwhile, A Corp. had defaulted on its obligations to X Bank, which held a loan claim of approximately ¥329 million (due April 4, 1996) secured by the root mortgage on the Building. X Bank moved to exercise its right of subrogation over the rental income. It applied for and obtained a court order attaching A Corp.'s rent claims against Y Corp. for rents falling due after the service of the attachment order, up to a total of ¥9 million. This attachment order was issued on January 23, 1998, and was served on Y Corp. (the lessee and third-party obligor of the rent) on January 24, 1998, and on A Corp. (the lessor and X Bank's debtor) on January 28, 1998.

- The Collection Suit: X Bank then filed this lawsuit (a collection suit, toritate soshō) against Y Corp. to collect the attached rents directly from Y Corp. Y Corp.'s primary defense was that its rental obligations had already been extinguished by the set-off agreement it had made with A Corp. concerning the unrefunded security deposit.

The Legal Question: Priority Between Mortgagee's Subrogation and Lessee's Set-Off

The lower courts (both District and High Court) had ruled in favor of X Bank. They rejected Y Corp.'s set-off defense, generally reasoning that X Bank's mortgage, having been registered and thus made public, took priority over Y Corp.'s later-arising right to set off its claim for the security deposit refund against the rent. The High Court specifically held that because the mortgage registration publicized the mortgagee's potential right of subrogation, and Y Corp.'s lease (under which its security deposit claim arose) was entered into after the mortgage registration, X Bank's subrogation via attachment should prevail over Y Corp.'s attempted set-off. Y Corp. appealed to the Supreme Court, arguing that, at least concerning the third-party obligor (the lessee), the service of the attachment order itself should be what constitutes effective public notice of the subrogation right, not the much earlier mortgage registration.

The Supreme Court's Judgment (March 13, 2001): The "Registration Date Standard"

The Supreme Court dismissed Y Corp.'s appeal, thereby affirming the lower courts' decisions in favor of X Bank. The judgment established what is often referred to as the "Registration Date Standard" for this type of conflict.

- The General Rule on Set-Off Post-Attachment: The Court held that once a mortgagee has exercised its right of subrogation by attaching the rental income claims, the lessee of the mortgaged property cannot assert a set-off against the mortgagee by using a claim (as the active claim for set-off, jidōsaiken) that the lessee acquired against the lessor after the date the mortgage was registered.

- Rationale for the Rule: The Supreme Court provided the following reasoning:

- Before Attachment: The Court acknowledged that before the mortgagee executes an attachment for subrogation, the lessee's ability to effect a set-off against the lessor based on a valid claim is generally not restricted.

- After Attachment: However, once the mortgagee's attachment is in place, the mortgage's effect extends to the attached rental income.

- Publicity of Mortgage's Potential Effect on Rent: Crucially, the Court stated: "...the fact that the effect of the mortgage extends to the rental income which has become the object of subrogation can be considered as having been made public by the registration of the mortgage securing the principal obligation." This echoes a principle articulated in an earlier landmark Supreme Court case concerning subrogation versus assignment of rent (Supreme Court, January 30, 1998, Minshū Vol. 52, No. 1, p. 1 – the "M84 case").

- Lessee's Expectation vs. Mortgagee's Right: Therefore, if a lessee acquires a claim against their lessor after the mortgage on the leased property has already been registered (and thus, after the mortgagee's potential claim on rents has been, in the Court's view, publicly signaled), the lessee's expectation of being able to set off this later-acquired claim against future rent (which is now targeted by the mortgagee's realized subrogation right) does not deserve to take priority over the mortgagee's established security right.

- Effect on Pre-existing Agreements for Future Set-Offs: The Court also addressed the scenario where, as in this case, the lessee and lessor had a prior agreement to set off future rent payments against a debt owed by the lessor to the lessee. It held that even with such an agreement, if the claim which the lessee intends to use for the set-off (here, the security deposit refund claim) was acquired by the lessee after the mortgage was registered, then the lessee cannot assert the effect of this set-off agreement against the subrogating mortgagee for any rental payments that fall due after the mortgagee's attachment order has been served.

- Application to the Facts: In this case, Y Corp.'s claim for the refund of its security deposit (the active claim it sought to use for set-off) effectively arose or was crystallized in its specific amount after X Bank's root mortgage on the Building had been registered. The set-off agreement between A Corp. and Y Corp. pertained to future rents, many of which would fall due after X Bank's attachment order was served on Y Corp. Consequently, Y Corp. could not use its set-off agreement to defeat X Bank's claim for these post-attachment rents. The High Court's conclusion was therefore deemed correct.

Key Principles: Mortgage Publicity and Lessee's Expectations

This 2001 judgment strongly relies on the premise, heavily featured in the 1998 (M84) Supreme Court decision, that the registration of a mortgage serves as a form of public notice not only of the lien on the real property itself but also of the mortgagee's potential future claim, via subrogation, on the rental income generated by that property.

The Court's decision can be seen as balancing the interests of the mortgagee and the lessee. It prioritizes the mortgagee's security right if the lessee's basis for set-off (their active claim against the lessor) came into existence after the lessee had, or should have had, constructive notice of the mortgage through its public registration. The lessee's expectation of being able to set off such a later-acquired claim is deemed subordinate to the mortgagee's pre-existing, registered security interest that can extend to rents.

The "Window" for a Lessee's Set-Off

Interestingly, the judgment also explicitly states: "Before the attachment for the exercise of the right of subrogation is effected, a set-off by the lessee is not restricted in any way." This implies that if the lessee had actually effected a set-off (i.e., the mutual debts were extinguished by a declaration of set-off or by agreement with immediate effect) before X Bank's attachment order was served on Y Corp., that set-off would have been valid and effective even against X Bank, regardless of when Y Corp.'s underlying claim against A Corp. arose relative to the mortgage registration. In this regard, the Supreme Court appears to treat an effected set-off similarly to an actual "payment or delivery" of the rent to the lessor, which, under Article 304(1) proviso, would cut off the mortgagee's right of subrogation if done before the mortgagee's attachment.

This aspect differentiates the treatment of set-off from the treatment of assignment of rent claims as decided in the 1998 (M84) case. In M84, a perfected assignment of future rent made before the mortgagee's attachment was held not to defeat the mortgagee's subsequent subrogation. Here, an actual set-off effected before attachment would seem to defeat it.

Important Distinctions and Later Developments

The principles laid down in this 2001 judgment have been subject to further clarification and operate within a broader legal context:

- Set-off using a Security Deposit Refund Claim (Shikikin Henkan Seikyūken): This 2001 judgment, if applied strictly, might have made it very difficult for lessees to ever use their claim for the return of a security deposit to set off against rent if there was a pre-existing mortgage on the property. This is because a security deposit refund claim typically becomes an unconditional, due, and owing debt only when the lessee vacates the premises at the end of the lease, which would almost invariably be long after any mortgage was registered. This outcome was perceived by some as potentially harsh on lessees.

Recognizing this, the Supreme Court, in a subsequent decision on March 28, 2002 (Minshū Vol. 56, No. 3, p. 689, a case related to the M83 judgment), clarified that the application of a security deposit to cover unpaid rent upon the termination of a lease and vacation of the premises occurs naturally and automatically due to the inherent function of a security deposit. It does not require a separate act or declaration of set-off by the lessee. This automatic deduction takes precedence over a mortgagee's attempted subrogation against those specific rent arrears that are covered by the deposit. As a result, the principles of the 2001 judgment discussed here generally do not apply when the lessee's active claim for set-off is specifically their security deposit refund claim being applied in its ordinary course upon lease termination. - Interaction with "Secured Real Property Profit Execution": Japan later introduced a more structured system for mortgagees to collect rental income, known as "Secured Real Property Profit Execution" (Civil Execution Act Article 180 et seq., part of the 2003 reforms). The Supreme Court, in a 2009 decision (Supreme Court, July 3, 2009, Minshū Vol. 63, No. 6, p. 1047), extended principles similar to the "Registration Date Standard" from this 2001 judgment to disputes involving set-off in the context of these newer profit execution proceedings. That 2009 judgment also clarified that if the lessee's active claim (used for set-off) was acquired before the mortgage registration, the lessee can assert the set-off against the mortgagee or the court-appointed administrator even after the profit execution process has commenced.

- Impact of 2017 Civil Code Reforms: Japan undertook a major overhaul of its law of obligations, effective 2020. The rules governing set-off, particularly in relation to assigned claims (Civil Code Article 469) and attached claims (Civil Code Article 511), were revised. For example, the amended Article 511, Paragraph 2 allows a set-off against an attached claim even if the active claim was acquired after the attachment, provided the cause for that active claim existed before the attachment. These legislative changes are generally seen as more permissive towards the party wishing to effect a set-off. It is anticipated that these reforms will influence the future application of the balance struck by the 2001 Supreme Court judgment, potentially expanding the lessee's ability to set off against a subrogating mortgagee.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of March 13, 2001, established a significant "registration date standard" for resolving conflicts between a mortgagee exercising subrogation over rental income and a lessee seeking to set off their own claims against the lessor. By holding that a lessee generally cannot assert a set-off against the subrogating mortgagee using a claim acquired against the lessor after the mortgage was registered, the Court reinforced the publicity and priority effects of mortgage registration concerning rental income. However, the judgment also implicitly recognized a window for lessees to protect their interests by effecting a set-off before the mortgagee's attachment. This area of law remains dynamic, with critical clarifications for security deposit set-offs and substantial legislative reforms in 2017 continuing to shape the precise balance of rights among mortgagees, lessors, and lessees in Japan.