Mortgagee vs. Obstructive Occupier: Japanese Supreme Court on Right to Vacant Possession

Date of Judgment: March 10, 2005

Case Name: Claim for Vacant Possession of Building

Court: Supreme Court of Japan, First Petty Bench

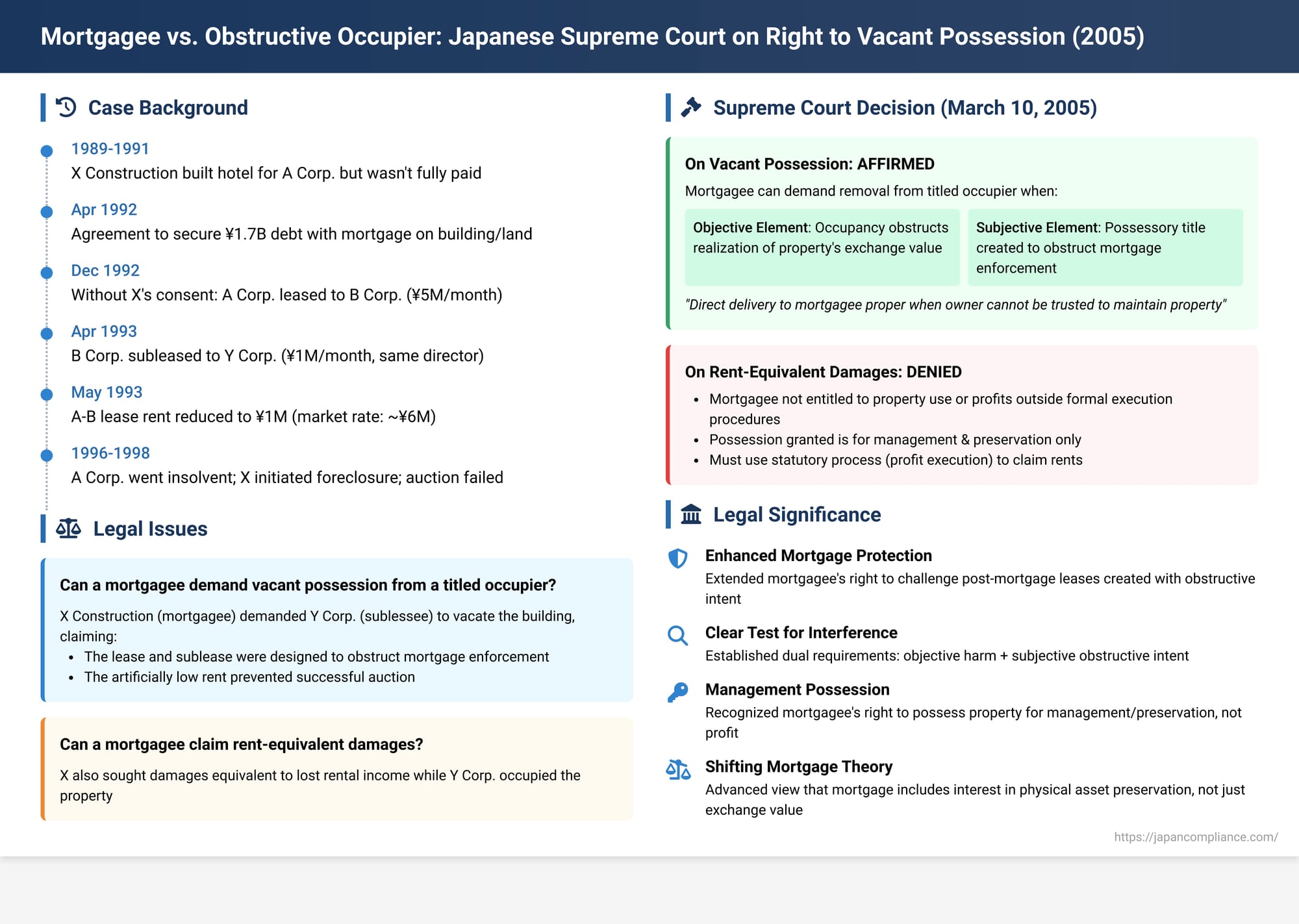

A mortgage provides a lender with security over a borrower's real property. However, the value of this security can be significantly undermined if the property owner, after granting the mortgage, allows third parties to occupy the property under terms that make foreclosure difficult or unprofitable. This often involves leases with unusually low rents, excessively long terms, or to affiliated parties, designed to deter auction purchasers or reduce the sale price. The Supreme Court of Japan, in a crucial judgment on March 10, 2005, addressed the extent to which a mortgagee can take direct action against such "obstructive occupiers," even if they hold a lease, to protect the mortgage's value.

The Hotel Dispute: Construction Debt, Mortgages, and Strategic Leasing

The case arose from a failed hotel construction project and subsequent attempts by the mortgagee to recover its dues:

- The Construction and Debt: In September 1989, X Construction entered into a contract with A Corp. to build a nine-story hotel with a basement (referred to as "the Building") on land owned by A Corp. The contract price was over ¥1.7 billion. X Construction completed the Building in April 1991 but retained possession because A Corp. failed to pay a substantial portion of the agreed price.

- The Mortgage and Other Agreements: In April 1992, A Corp. and X Construction reached a new agreement ("the Agreement"). A Corp. acknowledged the outstanding debt (over ¥1.729 billion) and agreed to a payment schedule. To secure this debt, A Corp. agreed to grant X Construction a mortgage ("the Mortgage") on the Building and its underlying land. Additionally, A Corp. was to grant X Construction a "conditional leasehold right" (teishi jōken-tsuki chinshakuken) over the same property, with the condition for its activation being events like the initiation of mortgage foreclosure proceedings by X Construction. This conditional lease was not intended for X Construction's actual use or profit but as an additional mechanism to secure the property's exchange value. The Agreement also stipulated that A Corp. needed X Construction's consent to lease the Building to any other party.

- Registration and Delivery: In May 1992, based on this Agreement, the Mortgage was registered, and a provisional registration for the conditional leasehold right was also made. X Construction then delivered possession of the completed Building to A Corp..

- A Corp.'s Breaches and Strategic Leasing: A Corp. subsequently breached the Agreement by failing to make any of the agreed installment payments. Furthermore, in December 1992, A Corp., without obtaining X Construction's consent as required, leased the entire Building to B Corp. for a five-year term at a monthly rent of ¥5 million, with a stated security deposit of ¥50 million.

- In March 1993, the security deposit for this A-B lease was purportedly increased to ¥100 million (though the actual payment of this increased sum was unclear).

- Then, in April 1993, B Corp., again without X Construction's consent, subleased the Building to Y Corp. for a five-year term at a significantly lower monthly rent of ¥1 million, with a stated security deposit/guarantee money (hoshōkin) of ¥100 million.

- In May 1993, A Corp. and B Corp. further agreed to reduce the rent under their primary lease from ¥5 million to ¥1 million per month.

- Evidence of Collusion: An expert appraisal indicated that the fair market rent for the Building was around ¥6 million per month at the relevant times, far exceeding the ¥1 million rent in the A-B lease (after reduction) and the B-Y sublease. Moreover, Y Corp. (the sub-lessee) and B Corp. (the primary lessee) shared the same representative director. Additionally, A Corp.'s representative director had also served as a director of Y Corp. during a relevant period.

- A Corp.'s Insolvency and Failed Auction: In August 1996, A Corp. became effectively insolvent after its bank transactions were suspended. In July 1998, X Construction initiated mortgage foreclosure proceedings against the Building and its land. However, despite significantly reducing the minimum bid price, no buyer could be found, and the auction was unsuccessful. Around this time, A Corp.'s representative made a demand to X Construction to release the mortgage on the land portion of the property in exchange for a mere ¥1 million payment.

- X Construction's Lawsuit: Facing this situation, X Construction filed a lawsuit against Y Corp., the sub-lessee occupying the Building. X Construction sought (1) vacant possession of the Building and (2) damages equivalent to lost rental income.

The Legal Battle: From Conditional Lease to Mortgage Infringement

X Construction's initial claim in the District Court was based on the infringement of its conditional leasehold right, which was dismissed. In the High Court, X Construction added an alternative claim: that Y Corp.'s occupation of the Building constituted an infringement of the Mortgage itself, and on this basis, sought vacant possession and rent-equivalent damages. The High Court accepted this alternative claim and ruled in favor of X Construction on both counts. Y Corp. then appealed to the Supreme Court.

The Supreme Court's Decision (March 10, 2005): A Two-Part Ruling

The Supreme Court delivered a nuanced judgment, affirming X Construction's right to demand vacant possession under specific conditions but rejecting its claim for rent-equivalent damages.

Part 1: Mortgagee's Right to Demand Vacant Possession – AFFIRMED (with conditions)

The Court established a framework for when a mortgagee can demand vacant possession from an occupier of the mortgaged property:

- General Principle against Unlawful Occupiers: Citing its own Grand Bench precedent (Supreme Court, November 24, 1999, Minshū Vol. 53, No. 8, p. 1899), the Court reiterated that if a third party (other than the owner) unlawfully occupies mortgaged property, thereby obstructing the realization of the property's exchange value and hindering the mortgagee's right to obtain preferential payment through foreclosure, the mortgagee can demand the removal of this obstruction as a claim for elimination of interference based on the mortgage.

- Extension to "Titled" Occupiers with Obstructive Intent: The Court extended this principle to occupiers who, like Y Corp., possess some form of title derived from the property owner (e.g., a lease or sublease) that was created after the mortgage registration. The mortgagee can demand such an occupier to vacate if two conditions are met:

- The creation of their possessory title (the lease/sublease) was objectively intended to obstruct the mortgage enforcement proceedings (foreclosure auction).

- Their actual possession, by virtue of this title, obstructs the realization of the mortgaged property's exchange value and makes it difficult for the mortgagee to exercise their right to preferential payment.

The rationale is that the property owner is expected to manage the mortgaged property appropriately and is not permitted to create occupancy rights designed to frustrate the mortgage.

- Direct Delivery of Possession to the Mortgagee: Furthermore, the Court held that if the property owner (A Corp.) cannot be expected to properly maintain and manage the property in a way that avoids infringement of the mortgage, the mortgagee (X Construction) can demand that the occupier (Y Corp.) deliver vacant possession of the property directly to the mortgagee.

- Application to the Facts: The Supreme Court found that the circumstances surrounding the lease to B Corp. and the sublease to Y Corp. (their creation after X Construction's mortgage, the unusually low rent compared to market rates, the high security deposit, the long terms, and the overlapping directorships between A Corp., B Corp., and Y Corp.) strongly indicated an intent to obstruct the mortgage enforcement. Y Corp.'s possession under these terms clearly hindered the realization of the Building's exchange value. Given A Corp.'s actions (breaching the payment agreement, entering into these obstructive leases, demanding a nominal sum to release the land mortgage, and its insolvency), A Corp. clearly could not be relied upon to manage the property appropriately to protect X Construction's mortgage.

Therefore, X Construction was entitled to demand that Y Corp. deliver vacant possession of the Building directly to X Construction. The High Court's decision on this point was upheld.

Part 2: Mortgagee's Claim for Rent-Equivalent Damages – DENIED

The Supreme Court, however, reversed the High Court's decision regarding X Construction's claim for damages equivalent to lost rent.

- No Direct Entitlement to Rent/Profits: The Court stated that a mortgagee does not, as a general rule, suffer damages equivalent to lost rental income merely because a third party occupies the mortgaged property.

- Rationale:

- A mortgagee, by nature of the mortgage right itself, is not entitled to personally use the mortgaged property.

- A mortgagee cannot acquire the profits (like rent) from the property's use except through formal civil execution procedures specifically designed for that purpose (e.g., subrogation over existing rent claims or the "secured real property profit execution" system).

- The possession that a mortgagee obtains through a successful claim for elimination of interference (as affirmed in Part 1) is for the purpose of maintaining and managing the property on behalf of the owner to preserve its value for eventual foreclosure, not for the mortgagee's own use or for deriving profit from it.

- Conclusion on Damages: The High Court had erred in awarding X Construction damages for lost rent based on mortgage infringement. This part of its judgment was overturned, and X Construction's claim for these damages was dismissed. The Supreme Court also dismissed the appeal concerning the initial claim for rent-equivalent damages based on the conditional leasehold right, reasoning that this specific lease was also for securing exchange value, not for use and profit, so its infringement didn't cause lost rent damages either.

The Evolving Right of a Mortgagee to Eliminate Interference

This 2005 judgment represents a significant step in the evolution of a mortgagee's power to protect their security in Japan:

- From No Interference to Subrogated Rights: Older Supreme Court precedents (e.g., up to a 1991 case) generally denied mortgagees the right to interfere with the possession of the mortgaged property. A major shift occurred with the 1999 Grand Bench decision, which allowed mortgagees to demand the elimination of interference from unlawful occupiers by exercising the owner's rights through subrogation.

- To Direct Rights Against "Titled" Obstructive Occupiers: The 2005 judgment builds upon this by recognizing a direct right of the mortgagee, based on the mortgage itself (not merely subrogation), to demand vacant possession even from occupiers who have some form of title, like a lease, provided that title was created with obstructive intent and its exercise harms the mortgage. This affirms what was previously a suggestion (obiter dictum) in the 1999 Grand Bench ruling.

- The Two Key Requirements: The judgment clarifies that for a mortgagee to oust an occupier who has a lease or other title granted by the owner after the mortgage, both objective harm (obstruction of exchange value realization, hindrance to priority claim) and a subjective element related to the creation of that title (intent to obstruct foreclosure) are necessary. Legal commentary suggests that the "obstructive intent" requirement is important to distinguish these harmful occupancies from normal, bona fide leases, especially given that current Japanese law (Civil Code Article 395, as amended in 2003) grants even certain unperfected leases a temporary right to remain after foreclosure (a grace period for vacation). Thus, a higher threshold is needed to justify immediate eviction of a lessee.

Mortgagee's "Management Possession": Rights and Burdens

A notable aspect of this decision is the explicit affirmation that if the owner is unreliable, the mortgagee can demand possession to themselves. This is not for the mortgagee's own use or profit, but for what legal commentary terms "management possession" (kanri sen'yū) – the mortgagee steps in to maintain and manage the property to preserve its value pending a successful foreclosure sale.

While this provides a powerful remedy, it also places practical burdens on the mortgagee, such as the costs of management and a duty of care (akin to that of a good manager under Civil Code Article 644). There isn't a straightforward mechanism under general mortgage law for the mortgagee to recover these management costs from the eventual auction proceeds as priority execution expenses. This contrasts with situations where a mortgagee might use formal civil execution provisional measures, such as applying for a court officer to take custody of the property, where custody costs can be treated as common benefit expenses.

Damages: Why Not Rent-Equivalent? And Other Possibilities

The Supreme Court's denial of rent-equivalent damages is based on the principle that a mortgagee is not inherently entitled to the profits from the property outside of specific legal procedures designed for profit realization (like subrogation over existing rents, or the "secured real property profit execution" system – tampo fudōsan shūeki shikkō).

This aspect has drawn academic comment. Some argue it effectively gives obstructive occupiers a "free ride" until formally evicted. Alternative arguments have been suggested, for example, that if the obstructive lease (with its artificially low rent) demonstrably reduced the amount of rent the mortgagee could have collected had they initiated a formal profit execution or subrogation procedure earlier, perhaps that specific loss could be claimed as damages, even if those formal procedures hadn't actually been started. Another avenue for seeking monetary compensation might involve using indirect compulsion methods if an occupier fails to comply with a court order (e.g., obtained via a provisional measure) to vacate.

Broader Implications for Mortgage Theory

This line of Supreme Court decisions, including the 1999 Grand Bench case and this 2005 ruling, significantly strengthens the practical remedies available to mortgagees against actions that impair their security. By allowing direct claims for the elimination of interference and, in certain circumstances, direct possession by the mortgagee for management purposes, these rulings suggest that a mortgage in Japanese law is increasingly viewed as more than just a right to the abstract exchange value of the property upon auction. It implies a degree of recognized interest in preserving the physical asset and its value from detrimental actions by the owner or third parties, even before foreclosure is completed. This continues to fuel academic discussions on the fundamental nature of mortgage rights.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court's judgment of March 10, 2005, marks a crucial development in protecting the rights of mortgagees in Japan against occupiers whose presence is intended to obstruct or devalue the mortgage security. It affirms a direct right for mortgagees to demand vacant possession from such occupiers, even if they hold a lease, provided specific conditions demonstrating obstructive intent and actual harm to the mortgage are met. This possession, however, is for management and preservation, not for the mortgagee's personal profit. The clear denial of direct claims for rent-equivalent damages in this context reinforces the principle that realizing monetary profits from a mortgaged property requires the mortgagee to utilize formal execution procedures designed for that purpose, such as subrogation over rents or the statutory profit execution system. This decision provides important clarity for lenders, borrowers, and tenants regarding their respective rights and obligations when a mortgaged property is occupied under potentially contentious circumstances.